It’s Friday night and you’re going to see your favourite band perform. You smile at the bouncers at the venue and they let you beat the queue. The guy who stamps your arm hugs you extra tight, winks, and tells you this dress makes you look good and hopes you are coming to the house party later.

You nod yes.

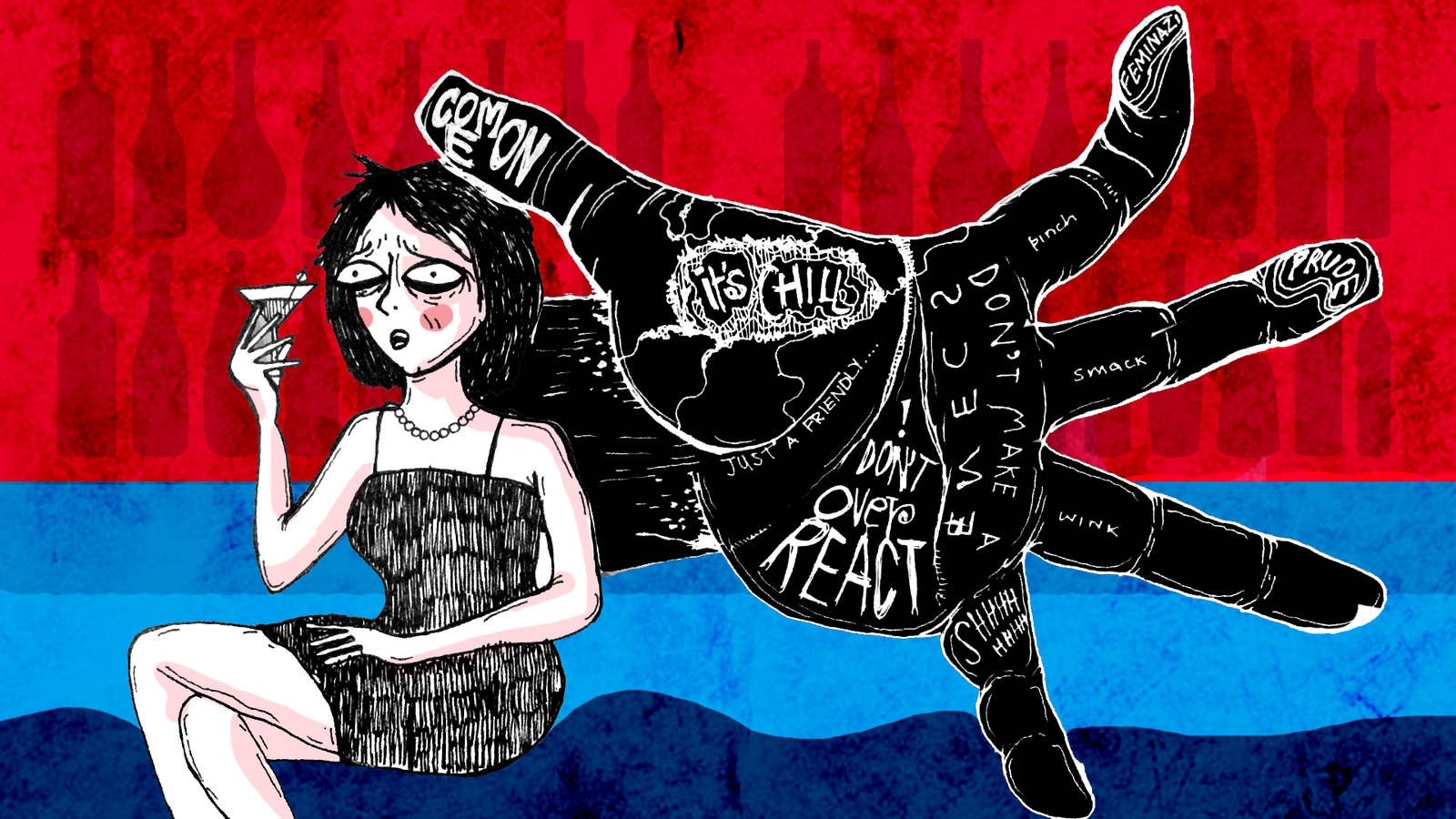

You’ve been indoctrinated into the tribe of the “chill girl”.

You get entry to exclusive events, free drinks, and so much more when you’re a chill girl.

You’re in a new city with a new crew, and the blinding sort of freedom you’ve never experienced before. Last year you were doing board exams, and this year your friend runs a drinking establishment.

It’s cool to be a chill girl.

Before I fully understood how the High Spirits Cafe operated, I included it in a travel guide to Pune I once wrote. “There are dress-up nights, nights dedicated to karaoke and bingo, nights with booze at ‘vintage’ (read: cheap) prices, and plenty of live comedy and music. It’s a modern day member’s club, with a clientele that’s more sprightly and more loyal.”

At the time, I thought High Spirits' business model was exemplary. The programming on offer was unparalleled – some of the biggest names in India, from Pentagram and Soulmate to Nucleya and comedians like Vir Das and Kanan Gill regularly performed here, not to mention top international acts like Mumford and Sons, Karsh Kale, FKJ, and Skyharbor, which dropped in on occasion.

High Spirits was easily one of the top venues in the country, a champion of the indie scene.

Every artist wanted to perform there, and consequently, the place was always packed – most often with young, well-off college kids, freshly arrived in Pune from all over the country.

But in May 2016, my understanding of High Spirits changed significantly. A guy I met briefly at a house party put up a Facebook status that said, “What do you call a woman with an opinion? Wrong.”

I called him out on it and the argument got ugly, so I blocked him – but not before Khodu Irani, the owner of High Spirits, decided to draw attention to our argument, calling it the “most entertaining thing he’d ever seen”.

He then messaged me in private to ask, “you’ll come out the loser na so what do you gain doing this?”

I took the discussion to my own page, where the trolls – mostly Irani's friends and High Spirits loyalists – descended. When the tone policing and free speech arguments didn’t work, Irani and his army of supporters attempted to silence me with some good old-fashioned bullying. They photoshopped me and the argument into memes that were then shared on their Facebook group, High Homies, which has over 4,000 members.

He then called mutual friends who protested to defend himself and make sure they were returning to the venue, “You know I’m not sexist bro.”

Later that year, the joker received a “Sexist of the Year” award at their annual year-end bash. Other awards presented at the party included ones for best breasts and best ass.

It had become apparent to me that High Spirits’ carefully constructed aura as “the place to be” for Pune’s young and restless was merely a facade. Beyond the smoke and mirrors lay a toxic community that was starting to come into view.

On 11 Oct 2017, five days before #MeToo went mainstream, I tweeted about High Spirits.

Last year I was publicly shamed on the Facebook page for an extremely popular bar called High Spirits in Pune for calling out sexism

I had no idea then that I would end up eventually giving voice to the anguish of hundreds of women – and a few men – who had been too afraid to speak out before.

Why hadn’t they spoken out?

Rape culture.

Allow me to explain.

In the days and weeks that followed my tweets, my inbox unexpectedly became a confessional booth for victims and witnesses to share their stories. The messages alleged abuse – verbal and physical – not just by Irani, but also his staff and regular patrons. The ringleader had, for years, fueled the toxic masculinity that empowered a community of blatant harassers.

It turned out High Spirits’ culture of sexism was an open secret.

And the reason this secret took so long to spill out has to do with the fact that High Spirits has long enjoyed the kind of reputation usually reserved for institutions. An anonymous statement put out by a regular explains how Khodu meticulously built his establishment’s name. “He’d gift regulars bottles of champagne, host special occasion parties, send birthday gifts, ensure access on days where the others would line up for hours. The amount of effort he invested in making High a personal experience is staggering.” The statement concludes that “he’s used this as a get-out-of-jail-free card for his misbehavior.”

In another anonymous account, published by the Quint, the author painted a vivid picture of how the irresistible allure of High Spirits made young college students feel like inappropriate behaviour was a perfectly reasonable trade-off. They were, after all, chill girls.

“Winks to the cleavage, butt pinching, and all these gorgeous women didn’t mind it. So for me, that was the currency to becoming popular. 'Harmless petting' of my body parts. ... I didn’t understand if I had the right to shove a man who placed a sticker on my breast or held me a little too tightly on the waist. Because in the ecosystem called ‘High Spirits’, these were social currency.”

None of this is accidental. High Spirits went the extra mile to make itself feel like home, using the guise of family, to insulate itself. Abusers are almost always narcissists and master manipulators putting in the hard work to ensure cultlike loyalty. We know this by now. We learned it from the stories of Harvey Weinstein, of Louis C.K., of Mario Batali.

In the beginning, anybody who spoke out or amplified my voice got a phone call from Irani. The easiest way to save face was to call out my credibility and label me an attention seeker. His first public statement, published by BuzzFeed, calls me a liar with a vendetta.

But a few days later, he went on vacation. While he was away, employees and friends set up meeting with regulars to dispel concerns, WhatsApp messages were circulated urging patrons to send in a good word, and a flock of loyal women descended on the first piece of press to express their solidarity with him.

When the "family" is your public relations machine, you can take a holiday despite serious allegations of sexual harassment.

A Facebook post by another regular hit the nail on the head when it described High Spirits as “like other homes, other families. Where sexism hung over our heads, where it was hard to pinpoint the discomfort, where it was hard to bring it up at the family table for fear of tainting the home. For fear of no longer being welcome at home.”

It took a public statement from Divya Desa, an ex-employee of High Spirits, for people to begin acknowledging their complicity. In her Medium piece, which went viral, she recounted several horrifying instances of workplace harassment including a “daily routine” of “groping (butt and boob), body-shaming, slut-shaming, pinching, bullying, intense verbal and emotional abuse.”

Artists and customers alike admitted they had been privy to the harassment. “I was there when the beer was poured on her I’ve seen her cry in corners... In an attempt to 'fit in', to be one of the cool people who knew everyone at High, I forgot where the line should have been drawn,” said one regular patron and promoter.

This is why conversations around consent are essential. The line of conduct at High Spirits was blurry and malleable.

One victim’s statement described how she was never afforded the power of establishing that line herself, “The comments, name-calling, and groping always took me by surprise. I never asked for it, never consented to it, and never returned the ‘favour’. Consequently this line kept getting pushed and expanded while I made excuses for his behaviour, laughing and thinking ‘it’s only Khodu ya’.”

Those four final words echo across the accounts. The behaviour was not only justified, it was painted as harmless, a trait of endearment, even.

Rape culture is never simply limited to sexual harassment. It includes the dehumanisation of women in myriad ways – “reminding women of their place” by humiliating them in front of their friends, commenting on their weight “for their own good”, reducing them to their bodies by objectifying them, policing them, or making rape jokes.

Whenever victims at High Spirits protested, they were gaslighted into believing they were overreacting, that there were more important issues and bigger problems in the world. They were told to "chill". After all, nobody likes a girl who isn’t chill.

Whenever victims at High Spirits protested, they were told to "chill".

Comedian Tanmay Bhat tweeted an experience of being groped by Khodu on stage during his set “coz I'm overweight.” A queer patron shared a story of being harassed at a cross-dressing-themed event. “Khodu’s bouncers/bartenders were throwing sexual innuendos at me...because I took the theme so 'seriously' I suppose.. calling me 'chakke' n all that.”

Homophobia, transphobia, and fatphobia are each examples of toxic masculinity, which thrives on the humiliation of anybody who does not fit into the limiting ideals of what is acceptably masculine.

Though dozens of men wrote to me in support, with screenshots or with their stories, almost all asked for anonymity. Nobody wanted to be seen taking the side of women. Toxic masculinity requires men to act like "one of the guys". Those who speak out are met with a "just chill, bro". Toxic masculinity loves a chill bro because a chill bro sustains rape culture.

I began to observe the patterns, and the power structures at play became clear as day. The perpetrators had preyed on the youngest, most impressionable, and least well-connected. Teenage college students and the city’s new arrivals as well as people who (or whose parents) weren’t known, wealthy, or powerful.

Knowing exactly who to target is a must-have in the manipulator’s toolbox because it also becomes their greatest defence should they be found out.

As High Spirits’ culture of harassment became the city’s favourite dinner table conversation topic, a columnist wrote about how she initially threw her support behind him because she “would never imagine him capable of such behavior”.

“This couldn’t have happened. We’ve been sending our girls there for years,” said members of influential families.

The former joint commissioner of police was quoted saying, “I met Khodu when I was a member of the Poona Club ... To me, Khodu is an extremely wellspoken man and has a multifaceted, literary bent of mind.”

Where rape culture is the status quo, apologists are its citizenry.

I was called a feminazi, an ISIS agent, and a career destroyer. Survivors were dismissed (“I never saw it or it never happened to me, so it doesn’t happen”), slut-shamed (“I’ve seen what these chicks wear”), or blamed (“Why didn’t they speak out sooner? Why did they go back there?”).

The hashtag #HighHomieForLife appeared on social media, accompanied in at least one instance with a raised middle finger.

It’s not too difficult to understand why this was the community’s reaction. Relationships are built on trust. High Spirits’ supporters were unable to fathom how they had been misled; perpetrators and allies couldn’t compute why all their acts of goodness had been discounted.

Rape culture is ultimately an environment in which sexual harassment is trivialised. It is a society that states that women “allow this to happen” or that their allegations are “baseless”, where every single person who rallies behind the perpetrator, or attacks the victim is complicit in that sexual violence, and is responsible for widening the power differential between the two.

It is this distrust of victims that keeps them silent. Simply listening or saying "I believe you" cedes space for survivors to speak out. Denial, blame-shifting, and defensiveness derail the conversation around harassment.

I’m writing this piece nearly three months after the incident because High Spirits has resumed business as usual.

Indie music label Ennui.Bomb is programming gigs, members of the Reggae Rajahs and Bombay Bassment recently played here, and Chennai-based band Sapta, which issued a statement in October saying they were "upset by the allegations" and "left with no choice but to call [a gig] off", recently overcame their misgivings to perform there. More artists will presumably follow suit in the coming days and months. The turnout, which dipped in the wake of the outpouring of allegations, is also on the rebound.

Rape culture is a community that has moved on from an incident without believing redressal is necessary, sending the message that we’re tolerant to harassment.

Speaking up is imperative to instigating change. It’s tough to admit the people we trust do terrible things but silence is privately consenting to their bad behaviour. In a society where rape culture is dominant, abiding disapproval of friends and family is practically an act of anarchy. The onus of dismantling rape culture is not on one person but an entire community.

Holding people accountable cannot be misconstrued for attacking them. Allegations might shake up communities but silence hurts them.

Chill is ultimately dangerous.

I'm so done chilling.

This story includes instances of harassment from over a dozen different individuals and witnesses because rape culture tells us one isn’t enough.

Sheena Dabholkar is the creative director of Lover. She’s @sodonechilling with rape culture.