In his new book Between the World and Me, Ta-Nehisi Coates writes almost dreamily about the Mecca for black education in this country, Howard University. In the midst of a passage on his time there, Coates takes the reader on a pleasant tour of The Yard, the central greenspace set against the eastern sky, on hilltop high, where women (or rather, “girls”) are initially described by their attire:

There were the scions of Nigerian aristocrats in their business suits giving dap to bald-headed Qs in purple windbreakers and tan Timbs. There were the high-yellow progeny of AME preachers debating the clerics of Ausar-Set. There were California girls turned Muslim, born anew, in hijab and long skirt. There were Ponzi schemers and Christian cultists, Tabernacle fanatics and mathematical geniuses.

Though my time at Howard was a few years after his, the same types (and maybe some of the same actual people) were there when I was at the Mecca, too. I was a California girl who — if not born anew — at least learned how to be black at Howard University. When I say black, I mean that I learned to understand the deep DNA of a blackness that Coates invokes so beautifully when he rhetorically asks his son to consider the question “How do I live free in this black body?”

But what I didn’t know then — what I’ve only recently understood — is that I was learning blackness, this specific, thrumming, lung-filling, American blackness, from women. My mother isn't American; she taught me how to cook amazing Jamaican food and how to sew and quizzed me on math and praised my middle school newspaper movie reviews and told me stories of her mother killing chickens in di ya'd and late-night crab boils on the beach and writes "Many Happy Returns" on my birthday card every year. But she didn't and couldn't teach me the trappings of American blackness.

And by “black,” I don't mean genetically — obviously, Dolezals of the world aside, having parentage of African descent qualifies one as black. And by “black,” I don’t mean accepting of violence or “hood” culture. Coates describes the fear he grew up with in 1980s and 1990s Baltimore, not as a sign of cultural blackness, but as a symptom of trying to live free in a world that would rather you did not. There is nothing inherently “black” about violence, whether it comes from the streets or from parents trying to save their children from those streets.

At Howard, my college friends would tease, "Shani, you aren't really black," because I preferred to listen to The Postal Service and read Sinclair Lewis and because I didn't know how to wrap my hair, or dance to “Nolia Clap” at a humid, dark house party, or say "nigga" with that specific, practiced ease. But college is for learning, and I learned how to do those things, fairly quickly and I learned them from women.

But those superficial things aren’t blackness either. It was through a deeper knowledge of the wide swath of blackness present at the Mecca, that I began to understand that which was only possible in a place where nearly everyone else, from the president to the groundskeepers, was also in a black body. This, at least, is how it worked for me. Blackness is something ineffable, tied up in pride and understanding of oneself; it’s urgency and ambition; it’s feeling an ease that’s only possible in a place where self-segregation took away (most, though not all of) the self-doubt imposed on us by racism and by race. Black people re-create this feeling in different places, from church to the club to grad chapter meetings.

When I was at Howard, the most frequently (jokingly) thrown around figure was that the freshman class was 7 to 1, women to men. Official numbers are somewhere around 65% female to 35% male. The sheer number of women on campus meant their influence was felt from all sides. Women were in student government leadership roles; women edited the student newspaper, The Hilltop; long beautiful lines of sorors celebrated themselves with chants and party walking; classes where women spoke up and weren’t in the habit of being talked over by men, well-dressed, well-heeled women who were trained to chase career success just as much as love.

Central to the black woman’s struggle to live free is to find professional fulfillment. I didn’t need to read a study saying that 22% of black women want to hold powerful positions at work (compared to 8% of white women); all I have to do is take a brief survey of the women I went to school with. They’re stunningly ambitious, deeply driven, and surprisingly entrepreneurial when they hit a ceiling — after all, in 2002, only 5.3% of managers were black women.

I learned how to be black from women, and it's with disappointment but not surprise that I report, having enjoyed Coates' book, and read the reviews that have followed, that the black male experience is still used as a stand in for the black experience.

On my desk is a paper-covered preview copy of Coates' book, marked up with some of his last-minute edits written into it in red. When he stopped by my office to visit a few weeks ago and I complained I hadn’t gotten a copy, he graciously dug around in his messenger bag and yanked the dog-eared paperback out from the bottom, and offered it to me. Holding his second book in my hands was thrilling, considering how far he's come from the days when he had a Typepad blog where his dad Paul and I were some of the earliest commenters. I say this not to soften what I’m writing here, but to point out that I've known him long enough, and well enough, and with enough mutual affection that I do not think anyone would disagree that we are friends.

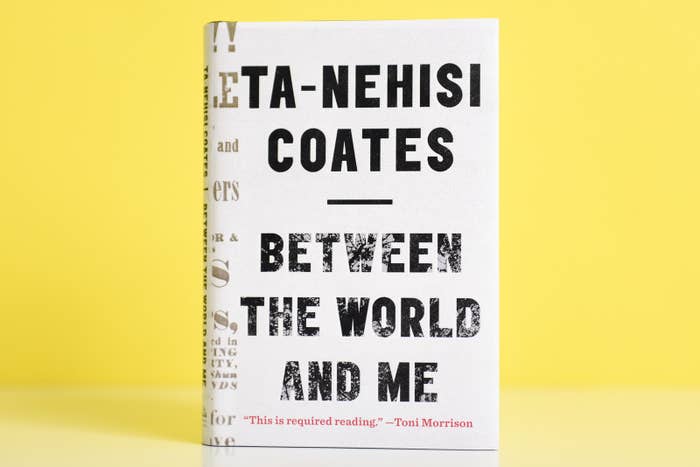

The hardcover, finished version of Between the World and Me has a quote from Toni Morrison inked in red at the bottom. It’s the final line of the blurb she gave him after reading it: “This is required reading.”

But what interests me is a different slice of the quote from Morrison, who has written life-changing novels of blackness and, in particular, black femaleness, which is this: “Its examination of the hazards and hopes of black male life is as profound as it is revelatory.”

I imagine that critics of my argument will say the solution here is for some black woman to write a book. But I know — and you know, even if you will not admit it — that this is not the answer. Did you know the first book published by an African-American (before there were African-Americans and even an America) was in 1773, by a woman named Phillis Wheatley? I learned that at Howard University. There is Alice Walker, and Toni Morrison, and Zora Neale Hurston. There is Isabel Wilkerson.

There have long been black women writing books. And yet, to talk about race is to talk about a struggle between black men and white men. The problem is bigger than Coates. The problem is that his book about black male life is one that many readers will use to define blackness. (Indeed, the New York Times' somewhat-critical review begins, “Between the World and Me is a searing meditation on what it means to be black in America today.”)

I read Between the World and Me on the train to and from work every day until I finished it. The cover is simple, and it’s bold, and reading his words, behind his name, printed in large block letters as though it matters, was simply inspiring. And it felt, just as Morrison said, like reading the intellectual successor to James Baldwin.

It’s a shame that the inclusion of black women in this work doesn’t seem to have progressed much further than Baldwin’s time, when the two requirements of being a “race man” are 1) being black, and 2) being male.

(Coates’ book being rushed to print is surely due, at least in part, to the very specific moment we’re in where America is being forced to confront the deaths of unarmed black men at the hands of police thanks largely to the #BlackLivesMatter movement, founded by queer black women.)

In Baldwin’s original Letter to My Nephew, he writes of white racists:

But these men are your brothers, your lost younger brothers, and if the word "integration" means anything, this is what it means, that we with love shall force our brothers to see themselves as they are, to cease fleeing from reality and begin to change it, for this is your home, my friend. Do not be driven from it. Great men have done great things here and will again and we can make America what America must become.

Coates does address the place of women, though largely in passing, to his son (page 71):

I am not a cynic. I love you, and I love the world, and I love it more with every new inch I discover. But you are a black boy, and you must be responsible for your body in a way that other boys cannot know. Indeed you must be responsible for the worst actions of other black bodies, which, somehow, will always be assigned to you. And you must be responsible for the bodies of the powerful—the policeman who cracks you with a nightstick will quickly find his excuse in your furtive movements. And this is not reducible to just you—the women around you must be responsible for their bodies in a way that you never will know.

This, of course, is true. But it is not all. Black womanhood in real life isn’t — as it largely is in Between the World and Me — about beating and loving and mourning black men and protecting oneself from physical plunder. It’s about trying to live free in a black body, just like a man.