On Father’s Day a few weeks ago, Kim Kardashian posted a photo of her late father, Robert. It’s a grainy, black-and-white shot from when she was a teenager, and thus her cheeks are plumper, her eyebrows thinner, and she seems to be wearing very little makeup. There are, predictably, thousands of comments underneath her caption (“You were the best dad in the world!”) begging for LB ("like back"), haranguing trolls, or marveling at the family resemblance. Among them are a handful of comments specifically about Kim’s nose, then and now. “Kim looked hella Armenian before her nose job,” says @kiki_lund. “Thank god she changes. Lmfao.” Another, @ourlityouth, says, “Aww she looked cute before the Botox , surgeries , liposuctions , butt implants, and nose jobs + many more,” followed by an emoji laugh-crying. @zonaooohlala19 is more succinct: “You got rid of the nose he gave u.”

Over the last few years, Kim’s visual ethnicity has become increasingly vague, with fuller lips and a lasered hairline and skin that glows gold instead of olive. Makeup has helped, of course, namely the contouring done on her nose, powdered to look its skinniest, its pointiest.

Kim herself has never confirmed rumours of nose alterations, but that hasn’t stopped anyone from speculating. One gossip site says she didn't get a rhinoplasty, but may have gotten “a non-surgical nose job,” which is somehow perceived as “better.” (NSNJs are done using injectable fillers that can straighten or lift or smooth. They can’t necessarily make a large nose smaller, but they can immediately correct small imperfections or offer better symmetry.) But Kim’s not the only famous woman accused of changing her nose. Judging by rumours, both Beyoncé and Rihanna have gotten nose jobs, and Nicki Minaj too. The Talk host Julie Chen admitted to getting eye surgery to make her eyes look “less Asian,” but denied getting a rhinoplasty. Gawker wrote that when she made this announcement on The Talk, the audience broke into applause “because there is acceptable plastic surgery and unacceptable plastic surgery.” Janet Jackson, meanwhile, has never been able to catch a break. She got a rhinoplasty at 16, and public discussion of her nose has ranged from mocking her about its current state to referring to her natural nose as “bulbous.”

Kim Kardashian in 2006 and 2016.

White women are accused of rhinoplasties as well, but for nonwhite women, there’s no winning. Either your nose is too big, and you’re criticized endlessly for it, or you fix it, and you deal with endless speculation over whether you were too weak to stick it out with your original face. For women of color in particular, colonial influences are forever felt in what we are told is beautiful, and who gets to be beautiful. Nonwhite women are, across the board, told that a proximity to whiteness is a proximity to beauty. Dark-skinned women like Gabourey Sidibe are photoshopped to make their skin look lighter and brighter. Skin-bleaching products promise glowing, pale skin, scarring and kidney damage be damned. Companies like Dove even promote skin-lightening deodorants that “reduce underarm dark marks.”

That said, countless traits of the female body are in the midst of some kind of turnaround, with attempts to turn the negative portrayals of it, the hatred for it, into something good. Nearly every vaguely ethnic marker of beauty has gone through an online moment of glory and adoration: Black women on Instagram praise their melanin-blessed skin; Indian women like me grow out their armpit hair, their sideburns, their treasure trails, and take photos of their defiant hair growth instead of hiding like so many of us were told to do. The body positivity movement is maybe the most heartening version of self-acceptance, where fat women — or, frankly, women of any shape tired of being told there’s something wrong with them — are celebrating their bodies. But the nose, or at least those of us with big, wide, crooked noses that have never been glorified, or fetishized, or romanticized, have yet to find a similar awakening. The nose is still considered a flaw in countless communities, a problem that needs to be fixed by breaking and reshaping. And the nose, regardless of where you are in the world, almost always needs to be slender, refined, and small. In 2015, rhinoplasty was the third most popular cosmetic plastic surgery in the U.S. (The first two were breast augmentation and liposuction.) More than 200,000 “nose reshapings” were performed that year, and 76% of those surgeries were on women.

The nose, then, is still awaiting a transformation where we love it for its shape rather than trying to transform it into something we already know to be acceptable. No matter where we are, or who we think we are, the beauty standards for noses are still remarkably narrow. If skin bleaching and hair straightening for non-white women have long since been related to an erasure of heritage, could nose alterations also be looked at as a way we mask our racial roots? Beauty is so frequently about an erasure of history, of ethnicity, and it's no wonder we’re still trying to hide our noses. The ubiquity of rhinoplasties reveals our narrow beauty standards, but they also, in a complicated way, function as an erasure of our ethnic history.

Recently, Lil’ Kim Instagrammed a few selfies with blonde hair, a smaller nose, and lighter skin. It’s the latest evidence of a transformation that she’s been undergoing for years now, one that brings her ever closer to looking traditionally “white.” Her nose in particular has undergone a few changes, now looking more pinched, narrow, and slender. In a 2000 Newsweek interview, she talked about her self-esteem issues when it came to her appearance. “Guys always cheat on me with women who were European-looking. You know, the long-hair type,” she said. “Really beautiful women that left me thinking, ‘How can I compete with that?’ Being a regular black girl wasn’t good enough.”

Even the faces of almost any Instagram model, including women who are otherwise ignored by the mainstream beauty industry (fat, nonwhite, nonbinary, nonconforming), tend to abide by a few characteristics: full lips, thick brows, and a cute nose. Black models also tend to have more pointed and narrow noses, and with the added popularity of contouring, everything looks brighter, sharper, less soft, less round. Indian actresses have noses that slope gently, no cracks in the cartilage from brow to tip. (Aishwarya Rai, arguably one of India’s best-known actresses, has some of the most Anglo features you’ll find on an Indian woman, from green-blue eyes to fair, creamy skin and a slender nose that neither protrudes nor flares.) Even Jewish women society deems "beautiful" rarely have noticeable noses. (Did you know Scarlett Johansson is Jewish? Yes, exactly.) Few cultures like or accept a large nose. No one wants a crooked one. Anything too wide, too flared is easily dismissed as unattractive, if not flat-out aggressive. This is true for nearly anyone, but doubly true for women, for whom anything outsized or out of the ordinary is examined and picked apart. In fact, the best nose, for women, is one you barely notice at all. Some of the most requested celebrity noses for rhinoplasties are Jessica Biel’s, Kate Middleton’s, and Angelina Jolie’s, all noses that are, frankly, relatively nondescript.

Jessica Biel, Angelina Jolie, and Kate Middleton.

There is a scientific explanation for what we generally might consider “beautiful.” A 2011 University of Toronto and UC San Diego study examined perceptions of beauty in the human face. Using measurements deduced from " the golden ratio," they found the proportions between facial features that are generally considered beautiful. These measurements include the distance from the hairline to the eyebrows, the distance from the Cupid’s bow to the tip of the mouth, and, finally, the width of the nose compared to the width of each side of the face.

The golden ratio doesn’t necessarily tell us what is more attractive, but rather what we generally consider more attractive.

“The point of this study isn’t to find what makes you beautiful, it’s to understand why,” says Pam Pallett, one of the co-authors of the study. The golden ratio doesn’t necessarily tell us what is more attractive, but rather what we generally consider more attractive. These ratios are the cumulative averages of all the faces we see over a lifetime which we perceive as attractive. “We know that faces that have extreme distances between the eyes and the mouth, or very small distances, atypical distances, between the eyes and the mouth, that those are not perceived as attractive,” Pallett says.

If you spent a lot of time around white people, you might find a Caucasian “average” the most attractive. “If you’re growing up seeing Chinese faces, you might have a preference for an average Chinese length and width ratio rather than a white person’s length and width ratio,” says Pallett.

But that’s merely the scientific level of what we find good-looking, and it hardly accounts for the biases we’ve accrued over time.

“A lot of anti-Semitic ideas that we think are eternal or long-standing were really introduced by art,” says Sara Lipton, author of Dark Mirror and professor in the Department of History at Stony Brook University. Lipton, a Jewish woman herself, studies religious identity and experience.

Lipton says that in the 13th century, Christian Europe in particular started to consider the physical body and what it meant. Before that, there wasn’t as much attention paid to physical features or skin colour. “Artists started portraying the body more realistically, and scientists, they started paying attention to the body,” she says. “The trend is clear: You can try to get some useful information from looking at people’s bodies.”

“The first images that show Jews with big noses show them not with love or compassion but with hate or anger at Christ,” Lipton says. “They’re not ethnic markers of a Jewish nose, but that these Jews are not feeling compassion for Christ.” The large nose, then, was less about what Jewish noses actually looked like and more about taking an ethnic group and linking them to something subhuman. “Beastliness, that’s really what the big nose signifies. Animals represent what is not controlled, what is not human, what is bad,” Lipton says. “That’s why the devil has the horns, he has a tail, the big nose.”

This theme of the Jew with the big nose continued, maybe best known in Nazi propaganda, where Jews were shown with large, hooked noses (along with puffy lips and a “deceitful” look, whatever that means). “People still have those assumptions because they’ve been trained by art, and sometimes very low art like caricature and newspaper cartoons, to believe in those assumptions,” Lipton says. “It contours the way you see the world.”

In a 2012 interview with Tablet, Elizabeth Haiken, author of Venus Envy: A History of Cosmetic Surgery, said that in the '20s, Jews, Italians, and Greeks were all seeking to change the shape of their noses. “There was a lot of anti-immigration sentiment and a lot of anti-Semitism once the immigration laws changed.” The same might be true now, regardless of race or ethnicity: If you want to blur the lines of where you’re from, where your parents are from, of who you are, a nose job is a good place to start. But while lips, eyebrows, eye colour, and hair texture can all be easily and fairly inexpensively altered, a nose is immovable with mere serums. Contouring, however — the process of highlighting desired facial structure (cheekbones, Cupid’s bow) while softening the rest (jaw, nose) — is starting to change all that.

Noted Beautiful Human Kim Kardashian is arguably the queen of “kontouring,” not the first to use it but certainly one of its most aggressive proponents, shaping her face into its most indistinct shape yet. She looks like she could be anyone, from anywhere, her hair in box braids but her nose gently sloped and thin, but her skin tanned bronze, but her hair thick and black. An Instagram photo Lil' Kim posted of herself and Kim K. shows the two women with glowing skin, thin noses, fanned lashes. Lil' Kim, with her expressly lighter-looking skin and slimmer nose, appears to be trying to morph into a white person. Kardashian, meanwhile, in an ice-blond wig, looks beautiful, and yet otherworldly — it’s easy to forget that she, once, looked remarkably like her Armenian father.

Recently, Kim said that she’s following a more minimalist makeup routine, forgoing her signature contouring. “I don’t think I’d stop contouring my nose,” she said. “I know people think I’ve had a nose job but it really is just makeup.” Indeed, rumours of a nose job have been following Kim around for a decade, comparing the pinched tip of her current nose to the far more Armenian-looking one she had in 2006, when she first started to become famous. Nearly all the nonwhite Kardashians have been accused of getting rhinoplasties at some point — especially Khloé, who gossip sites claim got a nose job to eliminate any resemblance to her alleged biological father, O.J. Simpson.

Then there’s her younger half sister Kylie, who is white but has embarked on a mission to look increasingly and indistinctly "ethnic," with tanned skin, full lips, and strong brows. You can even peep baby hair under some of her wigs, and she’ll often wear her hair in cornrows. Her cheekbones pop, the way I see the facial structure in my Indian family. But her nose, even long before she became independently famous from her sisters, has always been small, skinny. It’s the nose of a white girl.

Nearly all the nonwhite Kardashians have been accused of getting rhinoplasties at some point.

The push for cost-effective and quick nose reshaping has also led to products like Nose Secret, a $35-product that’s inserted into the nose to force it into a narrower, more pointed shape. The c-shaped, black plastic inserts come in three sizes and are made to be pushed into each nostril, forcing your nose to a tip while pulling your nostrils — if naturally flared — in. (Their founder, Fabiola Diamond, repeatedly tells me they “refine” the nose and can be used for daily wear but are mostly intended for special occasions. She references “photo shoots” as an example.)

On YouTube, there are plenty of user testimonials for the product—primarily from women (specifically nonwhite women) trying them out. One user, MissUniversal1000, who is black, shows you her nose before applying the inserts. “And now I will show you the full extremity of the full flare of my nostrils,” she says in a voiceover. “Large. Yep. Very large,” she sighs.

When she inserts one of the sets, she can notice a change immediately. “If you look at the tip, my nose has now become extended,” she says. “It’s more defined.” She tries every size, from XS to XL, in increasing pain while her nose gets more and more narrow, more upturned, the larger sizes pulling her lip up as well. She admits it hurts.

And they really do hurt. Things are not supposed to go up your nose, and painful plastic stents that push against the tip of your nose are hardly the exception. When I tried them on myself, the small version fell out, but the medium hurt so much my eyes kept welling up in tears. I didn’t even notice a change — my nose was still the same size. Of course it was. An insert doesn’t take away cartilage.

One of my co-workers, however, noticed immediately. “Your nose is so much smaller!” he said, tilting his head to get a look at me from all angles. “It’s amazing, man. It’s so much smaller.”

In 2010, researchers discovered that Queen Nefertiti's bumpy nose might have been smoothed down in the famous 3,300-year-old sculpture of her face, complete with high cheekbones and full brows. Though her name quite literally means “the beautiful woman has come,” her perceived flaws were still softened: a bent nose, wrinkles around the eyes, cheekbones not as prominent. A paragon of beauty, she was cemented in time as slightly more physically palatable.

In countries like Iran, rhinoplasty is so common that Tehran was dubbed the nose job capital of the world, with seven times more surgeries than in the U.S. Sunny Shokrae, a New York–based photographer, moved from Iran to the U.S. at age 5. “I used to push the tip of my nose up with my index finger, hoping it would stay that way,” she says. “It wasn’t until my early twenties that I stopped caring about it.” Nose jobs were completely acceptable, almost encouraged, for girls like her. “The operation is a marker not just of physical beauty but also of wealth and social priorities,” she says. “They want their features to be delicate, symmetrical, and European.”

Brownness and noses are inextricably tied; for both men and women, they tell us about identity and belonging.

Brownness and noses are inextricably tied; for both men and women, they tell us about identity and belonging. Rupi Kaur, a Toronto-based poet and author of Milk and Honey, grew up in a predominantly brown area but resented her Punjabi nose all the same. “I think it’s because we look so much like the Other, that you’re only beautiful if you’re like that Caucasian standard of beauty,” she says. “In high school, I started saving up to get a nose job, which is so ridiculous. I had this job at Tim Hortons and I was trying to save up $10,000 for a nose job.” In her university years, Kaur made peace with her nose, but in her early twenties, she discovered the thing that always subverts a young woman’s blossoming self-esteem: the internet. “It’s randomly resurfaced recently, almost because of Instagram. Everyone, or the people our age, are so damn beautiful and perfect, and you’re like, goddamn, I feel like complete shit,” she says. “As a woman, this brings me back to when I was 15. Who the hell wants to feel that again?”

Kaur says she discovered the Kardashians' plastic surgeon, Dr. Simon Ourian, on Instagram, creating a renewed fixation on her nose. “It’s weird because I’m so about the self-love, and then you spend 20 minutes on that man’s account and you want to just take your face and go to him and be like, ‘OK, fix me,’” she says. (She says she has since changed her settings on the Explore tab on Instagram, so now “I only see Beyoncé, which is fine.”)

Nose critics within brown communities, though, are plenty vocal. “Why are brown women bullying brown women for body hair. Why are brown women bullying brown women for the same traits we all have?” Kaur says. “They’re also trying to live in the West where they aren’t seen as ideal.” But even if you aren’t a part of the diaspora, Western ideals are still of top concern for plenty of brown women. So much about us is considered beautiful now — big eyes! Thick brows! Long hair! Cheekbones! — but the biggest “flaw” is still the centre, literally.

When nonwhite women engage in beauty norms, we also have the unfortunate task of examining whether we’re doing it because we like it, or whether it brings us closer to whiteness. When beauty brands sell us “complexion creams” to remove “dark spots,” are we actually being sold skin-whitening products? When we straighten our hair, are we doing that to hide our roots? For brown women, a smaller nose doesn’t only mean you’re considered more beautiful; it means that your family likely has the means to shrink it, which means you have money, which means you’re more marriageable. Brown women need to have slender noses and light skin above all, traits that few of us were actually born with. “It’s not so much about vanity as about the desire to join a class of Iranians who look European, read American books, travel, and live Western lives,” Shokrae says.

The things we find attractive in other people, in other races, isn’t always a “conscious experience,” as Pallett says. “That’s not to be confused with something being good or bad,” she says. “It’s really just an implicit perceptual thing. But it could create, at a very simple level, this additional desire for an individual to look more like that race, if that race is perceived as being better off.” Beauty, then, for those forced to consider class, race, gender, or sexuality, will invariably connect unconsciously to those we think are doing well. And comparatively, white women are doing great.

“It’s not just the Persians,” says Beverly Hills plastic surgeon Fardad Forouzanpour. “A lot of Armenian groups, a lot of Middle [Easterners]. Genetically, God gave us darker skin and said, ‘I’m going to give you bigger noses on top of that.’” Forouzanpour says he gets a lot of “ethnic” clients coming in for rhinoplasties, primarily women. Still, it’s so hard to identify why having a larger nose — or darker skin, for that matter — is so bad, especially for women. An oversized nose in the middle of your face can be distracting, sure, but since when did the nose become a hint to not only your physical beauty, but your economic and social status?

For black women, rhinoplasty may not be as common, but their noses don’t carry any less weight.

For black women, rhinoplasty may not be as common, but their noses don’t carry any less weight. “People view flared nostrils as a sign of anger and aggression. They view it as people acting more animalistic, so it’s a very easy way to stereotype black people,” says Ijeoma Oluo, writer and author of the forthcoming So You Want to Talk About Race. “To have the general facial structure of the majority of your population tied to animal aggression puts a lot of pressure especially on women, where so much of your value as a person is tied to how appealing you are to the majority. You’ll be lucky based on your features, or unlucky.”

But surgery is still hardly an accepted resort, particularly for nonwhite women, whose faces are monitored and policed differently than their white or male counterparts. “We do give some side-eye to other black women who’ve had work done, but at the same time, we don’t question the privilege of black women we say are beautiful,” Oluo says. “We can’t constantly look at every picture of a black woman with smaller noses and go, ‘Oh, look how beautiful black women are,’ and we’re only pointing at her, and at the same time give side-eye to black women who want to make a change.” If the standards of beauty are so rigid for black women in particular, who can blame someone like Lil’ Kim for wanting to be considered “beautiful” by everyone else?

A black nose, or any kind of large nose, has never been fetishized by nonblack people. Oluo thinks this is partly due to the fact that you can’t try on a large nose the way you can, say, box braids. “We look at traditionally what people would stereotype as Jewish noses and black noses, and these are things that oftentimes don’t cross over,” she says. “It’s very rare that you’re going to see a white person with the nose that a black person would have. That sort of thing means it’s not something white people can try on.”

Filmmaker Natalie Bullock Brown is currently working on a documentary on how Western beauty ideals affect black women, titled baartman, beyonce, & me. “The more Africanized a black woman’s features are, the less likely it is that she’s going to be considered beautiful or attractive,” she says. “A small nose, just like a small body frame, and pouty — even though they’re full — lips, is supposed to be dainty, and it completely plays into the skewed idea of what it means to be feminine.” The implications of a black woman’s physicality go back to slavery. “A broad nose, full lips, because of how enslaved black women were regarded, the narratives [were] spun to justify the sexual violence that was perpetrated against them,” Bullock says. “All this fullness feeds into this sexual deviance. We were seductresses and white slave owners could not resist us in the face of our hypersexuality.”

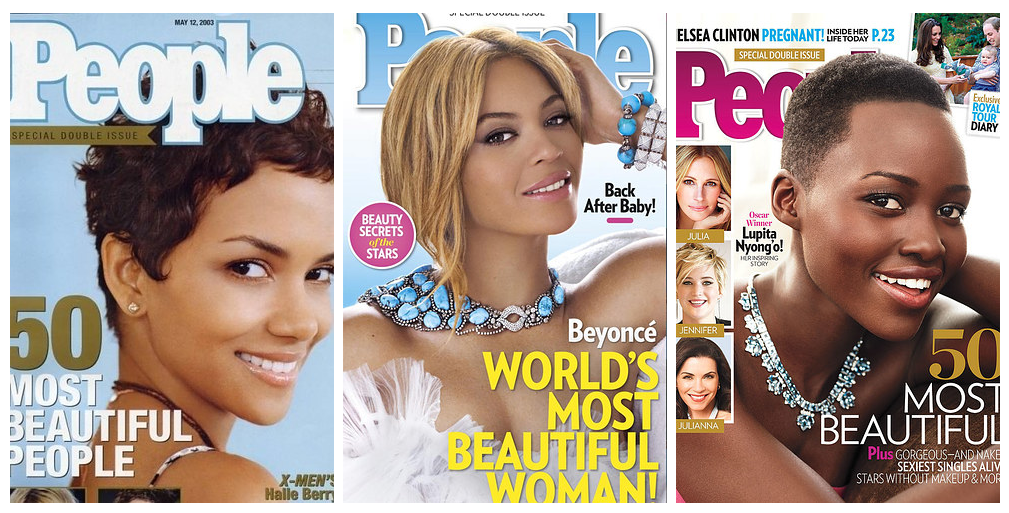

Though beauty standards are expanding, they’re still expanding within specific races and ethnicities. Brown women, for example, are still considered beautiful only if they have fair skin (comparatively) and slender features and big eyes and thin waists. Dark skin, wide noses, and frizzy hair are still hardly considered beautiful, but sure, your nose ring or the touch of yellow in your skin might be just enough to suggest you’re beautiful and ethnic. Black women have similar standards too, like the stereotype that East African women are more beautiful because of fairer skin, looser curls, more Anglo features. Bullock, for one, can’t think of a blatant appreciation for a larger black nose besides Beyoncé’s “Formation,” when she sings about Negro noses and Michael Jackson nostrils. Since the inception of People’s Most Beautiful list in 1990, there have only been three women of colour: Halle Berry, Beyoncé, and Lupita Nyong’o. “We are never in fashion. We are never the trend,” says Bullock.

But none of these features are objectively “better,” unless you tell yourself they are. “Right now we have this hierarchy: The closer you are to whiteness, the more valued you are, especially as a woman,” Oluo says. “The truth is that on a racial scale of desirability, we’re so far down on that Western scale, there are so many things considered unattractive about us by the majority of society, a nose job isn’t going to do much.”

Beauty is subjective, and we know that because things that have been beautiful in other communities and cultures — darker hair, darker skin, bigger lips, bigger butts — have slowly become popular here, in a white-dominated arena. The thing about your face is that if you stare at it long enough, you start to get used to it. Your nose, possibly more than any other facial feature you’ll have, tells the clearest story about your history, about where you came from, about where your parents and their parents and their parents came from. The slope of your cartilage, the way your tip is pointed or rounded, how your nostrils flare all tell a story that goes beyond just your face.

This can be a point of pride for some, or something that needs obscuring for others. It’s easy to hide other parts of our ethnicities with hair colour or texture, with skin-whitening creams that masquerade as “brightening lotions,” with contouring powder that give us the bone structure we never had. Our noses, however, are static, nearly impossible to hide and only partially changeable without major surgery. We’re able to find beauty in almost every other feature linked to our race, somewhere in the world, but the nose is unchanged. It forever tells you if, and where, you don’t belong.