Over the weekend, Dove apologized and pulled an ad it had posted on its US Facebook page for one of its body lotions. In the ad, a black woman pulls off her brown T-shirt, revealing a white woman in a cream shirt. (In the full GIF, the white woman pulls her shirt off to reveal a woman with a more olive complexion, but there’s still something queasy about the campaign and its tagline, “100% Gentle cleansers.”) “We missed the mark in thoughtfully representing women of color and we regret the offense that it has caused,” representatives for Dove said on Facebook after the company pulled the ad.

And this past April, Nivea got in trouble for an ill-advised ad campaign for its stain-free deodorant. Initially posted on Nivea’s Middle Eastern Facebook page, the ad depicted a woman sitting with her back facing the audience in a crisp, white shirt. The tagline? “White Is Purity.”

Unsurprisingly, Twitter and Facebook users went after Nivea. (The Facebook posting included the caption “Keep it clean, keep it bright. Don’t let anything ruin it.”) White supremacist groups praised the ad, saying that “Nivea has chosen our side.” Nivea pulled the ad the following day and apologized, explaining that it was a part of a broader campaign for the deodorant in the Middle East, implying that a North American (or white) audience wasn’t actually supposed to see it. This isn’t the first time Nivea has weathered a similar scandal; in 2011, it pulled and apologized for a promotion featuring a black man throwing away his own severed head with an afro and beard, along with the tagline “Re-Civilize Yourself.”

These are the most prominent examples of skin care campaigns gone racist, but if you look broadly at the company’s international marketing, you’ll find other ads that overtly (if more diplomatically) praise and prioritize whiteness. An ad for Nivea deodorant in India promised “visibly fairer and smoother underarms” that will give you “the confidence to be yourself.” Nivea’s Middle East YouTube page promotes a number of the company’s “Natural Fairness” products to keep your skin lighter. Nivea Philippines suggests “Extra White Body Cream” in order to “get whiter where you want!”

The racial coding of these ads isn’t as blatant as “White Is Purity,” but it is representative of the way skin care companies subtly calibrate their language when trying to market whitening products. Most North Americans are familiar with lotions, toners, or scrubs that “brighten” skin, products that are supposed to reveal a version of your skin that’s more glowing and “radiant.” But those products, or products like them, are sold in different regions by the same companies with just slightly different terminology. Brightening becomes whitening, and the pursuit of radiance becomes the pursuit of fair skin.

The phrasing around skin lightening products in North America isn’t different from the marketing in other countries because North Americans consumers are less racist, or because the North American beauty industry is less obsessed with whiteness as the highest form of beauty: It’s just because we’re more concerned with whether we appear racist. Consumers who were shocked by Nivea’s Middle East division promoting a deodorant with racist language were only surprised because they are rarely exposed to the language of beauty campaigns in countries where white people are not the majority. With these products, as in seemingly all things, our first priority isn’t dismantling our elevation of whiteness when it comes to beauty and status, but rather pretending that elevation isn’t happening at all.

Whitening products aren’t a new trend — plenty of communities have history with skin bleaching or home remedies intended to lighten the skin. Fair & Lovely, a lightening cream primarily sold in India, has become a cultural touchpoint for many brown women. Black women are often marketed to directly by cosmetics companies that make lightening or bleaching products. Plus, communities of color often have their own “cures” for darker skin whose ingredients vary from the natural (turmeric or honey) to the possibly carcinogenic (mercury). There’s also a long tradition of trying to suss out which celebrities might have bleached their skin: Sammy Sosa has undergone a very obvious change in complexion (which he admits to), Lil’ Kim’s skin is noticeably lighter (though she somewhat denies it), and — Beyhive forgive me — there are even conspiracy theories that Beyoncé is paler than she was a decade ago (which Beyoncé, of course, does not address).

Cosmetics companies in other countries aren’t under the same legal obligation as they are in the US to reveal their full ingredient lists, but most over-the-counter products — which are rarely labeled as skin bleachers — include some ingredient that could lighten your skin, even in the US. Those active ingredients vary from things you’d find in the kitchen to something like hydroquinone, which is only allowed in very low levels for nonprescription skin care. (Prescription skin lighteners can include more of that active ingredient.)

Skin bleachers often have more potent ingredients like mercury or steroids, some of which are banned in certain countries, including the US. Skin lightening or brightening products, meanwhile, are often sold over the counter, and suggest a more subtle shift in your skin tone (brighter rather than whiter) than flat-out bleaching. A lot of them are “natural” or “organic” since ingredients like citrus or liquorice root can also lighten the skin. These ingredients aren’t as potent as the ones you’d find in prescription bleachers, but they can make your skin fairer with extended use.

Part of the trouble with discussing brightening, whitening, or lightening products is that because those terms aren’t clearly defined, the marketing language isn’t regulated. Dr. Rachel Nazarian, a dermatologist in Mount Sinai’s Department of Dermatology in New York, considers whether the product bleaches or lifts stains from the skin in the same way you might evaluate how stains are removed from clothes when trying to make sense of these definitions. “When you have hyperpigmentation, you can actually bleach, meaning you’re preventing and interfering with the skin’s ability to make pigment,” she says. “Lightening is a bit different where you’re not bleaching or preventing the skin from making its pigment, but what you’re trying to do is to get the basic pigment to leave a little bit faster, sort of lift the stain, but you’re not interfering with the body’s pigment mechanism.” In other words, bleaching products will make it difficult to tan, since they affect your skin’s ability to create color. With brightening or lightening products, you can still form pigment.

Within the designation of lightening, or brightening, or even whitening, there are no real rules about what companies can or can’t say. “There’s no hard definition as to why one would use one label over the other, even though they are very different terms,” Nazarian says. “One can kind of interchange them.”

Although skin brightening products are ubiquitous across the globe, the way those products are marketed varies widely, depending on the market or the intended consumer. Skin lightening in countries like India, the Philippines, and China is often linked to the ideas of protecting your skin from the sun, revealing a better, whiter you, and connecting paler skin with marriageability or attractiveness. The Korean market is often interested in looking “porcelain” or youthful. For black and Latinx people, marketing for skin lightening products often references hyperpigmentation of certain body parts (lips, for example) while also noting that the products don’t contain harmful chemicals, like a lot of traditional bleaching products do.

Within the designation of lightening, or brightening, or even whitening, there are no real rules about what companies can or can’t say.

In North America, the same big companies that sell lightening or whitening products overseas — like Nivea, Vaseline, L’Oréal, Neutrogena, Dove, Pond’s, and Garnier — instead market spot treatments and “brightening” products, devoid of specific wording about skin lightening. The marketing language for these similar kinds of products is less about getting fairer skin and more about “detoxing” or getting an “even” skin tone, words that suggest more of a focus on health than skin color. (And it’s difficult to find brands that don’t engage in this sort of doublespeak with over-the-counter products, partly because so many beauty brands are owned by the same parent companies. Nivea and La Prairie are owned by Beiersdorf. Fair & Lovely, Dove, and Vaseline are all owned by Unilever. L’Oréal owns more cosmetics companies than you’d think, including YSL and Kiehl's.)

For example, Nivea Q10 Firming Body Oil, sold in Australia and Canada, promises to “even out your skin tone,” but Nivea Philippines UV Whitening Body Serum “delivers intense whitening” while repairing sun damage. These products aren’t necessarily the same thing — we can’t know without the full ingredients lists — but they do promise similar results with tweaked language. Neutrogena sells a Fine Fairness Overnight Brightening Cream in its Asian markets. (Neutrogena representatives told BuzzFeed News that you can’t buy the product in North America, but if you look hard enough you can find it on Amazon.) In the US, you can buy its Naturals Brightening Daily Moisturizer, which contains “skin-brightening lemon peel” and possibly reduces “the look of skin discoloration for visibly brighter, even-toned skin.” Dove, which created a US beauty campaign specifically dedicated to telling women they’re just fine as they are, sells a deodorant in North America that lightens armpits after they get darker, apparently, from excessive shaving. And while FDA regulations make it mandatory for companies like L’Oréal or Nivea to list all ingredients in US products, equivalent agencies are not obligated to do the same for similar products sold in places like India or the Philippines. It’s very possible their overseas products have ingredients that aren’t allowed in the US. (Conversely, there are ingredients in US-sold sunscreens that aren’t allowed in other countries.)

While niche brands are perhaps more honest about the intention of these skin care products, larger companies generally lean toward euphemism in their language. They seem to be targeting both people of color who are wary of a cultural bias toward lighter skin within their communities, and white people who are maybe less familiar, and less comfortable, with their preferred cosmetics brand getting into the whitening game.

Some skin care products can even be physically dangerous. Skin lighteners can cause both temporary and long-term damage to your body. We know what kinds of ingredients are in the brighteners sold in the US, but the same can’t be said for those products you purchase overseas. “I can tell you almost assuredly you’re not going to find 100% equal product ingredients,” Dr. Nazarian says. “A lot of the products I have seen coming from other countries, the result I’m seeing on my patients would indicate [that] a higher level contain bleaching agent.”

Regulations vary by country, but no region is entirely immune to the health risks of the worst kinds of bleaching creams. In 2010, the New York Times reported that dermatologists across the US were seeing Hispanic and black women with severe side effects from skin lightening creams, “many with prescription-strength ingredients,” in products like Hyprogel and Fair & White. In 2015, the Ivory Coast banned skin whitening creams, products like Femme Libre, because of their potential health effects. Some of those effects are minor irritations like inflammation, redness, burning, or flaking skin. In more extreme cases, whitening creams with hydroquinone, corticosteroids, or mercury can cause hypertension, kidney or liver damage, thin skin, or — if used while pregnant — birth defects.

No matter the product, the intention is the same: to make skin whiter. “It’s always to make skin whiter. Whiter in the sense of less pigment. Less pigment means more white,” Dr. Nazarian says. “It’s not lightening here and whitening there, I think that’s just the terms they feel the people understand in each culture. It makes money.”

Downplaying the true nature of these products has social ramifications, too. It allows companies to passively reinforce white ideals as beauty norms — ones we’ve had for centuries, long before beautification became its own industry — without explicitly acknowledging the benefits of perpetuating them. And in buying the products described with these euphemisms, white consumers don’t have to contend with the reality that the whiter your skin, the more beautiful you’re often considered to be.

Colonial standards of beauty for women have existed for a lot longer than products like Fair & Lovely have been available at drugstores. “These kinds of products have been around for a very long time, but mostly on an informal level,” says Margaret Hunter, a professor of sociology at Mills College. As the middle class has grown in countries like Brazil, India, and China, so has the cosmetics industry’s interest in reaching out to them. “It became in the interest of cosmetics companies to start marketing these products,” says Hunter. Thanks to colonialism, fairer skin still reads as a symbol of class and wealth. (Religion can play a part in this, too: Deities in Hinduism are often shown with light, glowy skin. Ravana, a symbol of evil, is often depicted with darker skin, hair, and eyes.)

In early 20th century, women in the US began using more skin care products daily. “For the products aimed at white women, it would often be about getting rid of freckles ... getting rid of skin that looked ‘dull’ and making it look brighter,” says Susannah Walker, author of Style and Status: Selling Beauty to African American Women, 1920-1975. Meanwhile, black people with fairer skin, dating from slavery days, were treated better by their white masters and, later, employers, which helped create a market for skin lightening products for black people. In the early 20th century, prominent black entrepreneurs who focused on hair care for black women, like Madam C. J. Walker and Annie Malone, started getting into the skin care game.

Neither was interested in getting into skin bleaching and lightening powders, but other black-owned companies did. (After Walker died in 1919, the Walker Company introduced a product called “Tan-Off.”) This perhaps led to more white-owned companies marketing directly to black people. According to Pageants, Parlors, and Pretty Women: Race and Beauty in the Twentieth-Century South by Blain Roberts, Nadinola, a bleaching cream product that’s still sold today, would run advertisements in black newspapers.

“The company connected light skin with social status, contending that Nadinola had lightened a socialite’s skin ‘three shades’ and finally given her the ‘fashionable light skin of other girls,’” Roberts writes. (Later, in the ’60s, Nadinola ran an ad in Ebony with a black woman wearing hoop earrings and an afro with the tagline “Black is beautiful,” a craven attempt to tell its market audience — black women — that they’re already attractive while also selling them something to improve themselves.)

During the 20th century, both black- and white-owned companies adopted language that focused on class and social standing, rather than whiteness, as the ideal. “Both types of companies, increasingly, are using a more ambiguous and complex language around the products,” Walker says.

Joanne Rondilla, the author of Is Lighter Better?: Skin-Tone Discrimination Among Asian Americans and a professor at Sonoma State University, believes that the shift in language across markets is largely about who is or isn’t comfortable with already present racial hierarchies. Her research focuses on language used in cosmetics advertising, largely in the Philippines, where words like “White Perfect” are often applied to market skin products. (Nivea’s Philippines website, for example, has an entire section for “Whitening & Beauty,” with one product called “Extra White.”) “When you consider the colonial history of the Philippines, and this notion of white and perfection, the product is sold as if continuing colonial language,” she says. “You can use the term ‘white’ in the Philippines because it’s understood this is what you aspire to.”

Thanks to colonialism, fairer skin still reads as a symbol of class and wealth.

It’s too simplistic to say that countries outside of North America are more comfortable with blatant anti-blackness when it comes to advertising skin lightening products, but they do tend to use more literal black-and-white language in their marketing. “I wouldn’t say the people in the United States, that blacks, Latinos, or Asians in the United States, are immune to those kinds of colonial pressures,” says Hunter. “But I think because of social movements here, like the Black Power movement and Black Is Beautiful, there’s a kind of hesitancy around wanting to actually identify as white. Instead people think, I wouldn’t mind my skin a little lighter or my nose being a little taller.”

In the North American market, most companies still think of white women as their default clientele. “When cosmetics companies visualize who their target market is, it’s not an Asian woman or a Filipino woman. It’s a white woman. Telling a white woman to retain her whiteness, it means something different in the US,” Rondilla says. And white consumers aren’t likely to respond to a product that explicitly claims to stifle melanin production, because it’s not a real concern for them.

Whitening products across the board in North America and on the other side of the world both do, however, engage with ideas of hygiene or detox. “It connects with the idea of hygiene, this idea that whiteness and cleanliness go together and that black or brownness are dirty,” says Hunter. “A lot of the old-fashioned remedies were about scrubbing the darkness out of your skin.” Hygiene advertising comes with the suggestion that darker skin is dirty and unattractive, or even that it might smell bad or cause revulsion if anyone else has to see it. Detoxing is essentially the same idea, repackaged for white women: a much nicer word that suggests you’re simply helping your body return to its natural, healthy state.

The fact that North American consumers don’t see a ton of products flaunting their whitening qualities may come down to white fragility more than anything else. “No one wants to think about their beauty process as participating in legacies of white supremacy,” Rondilla says. “Race speak is only acceptable if white people can find a way out of their privilege.” Ultimately, white people are uncomfortable with being reminded that beauty standards are still controlled by concepts of whiteness, regardless of your race. You’re still more likely to be considered attractive or get that job you want if you’re fairer skinned, and white consumers aren’t the ones who actually suffer from that reality.

Nayani Thiyagarajah is a director, producer, and documentary filmmaker based in Toronto. Her documentary Shadeism looks at colorism among indigenous, black, and other POC communities. “I’m from Sri Lanka and in the context of Sri Lanka, having experienced European colonial powers, I think that impacts ideas of shadeism and makes it worse,” she says. Thiyagarajah notices that language is blunter in Sri Lanka. “When they say someone is lighter skinned in Tamil, they say veḷḷai, which is white. If she’s getting darker, they say karuppu, which means getting blacker,” she says. “The language itself is so straight-up and matter of fact, and rooted in an anti-black racism.”

“You can use the term ‘white’ in the Philippines because it’s understood this is what you aspire to.”

The idea that it’s one thing to be brown or tan but another (worse) thing to be black is a real anxiety for a lot of South Asian communities. The language in advertising there may be less delicate, but even when people of color see cosmetics ads marketed to white people, they can read the code. “A lot of South Asians or other folks of color, when they see the word brightening, they know what that means automatically. It’s close enough without offending white people,” says Thiyagarajah.

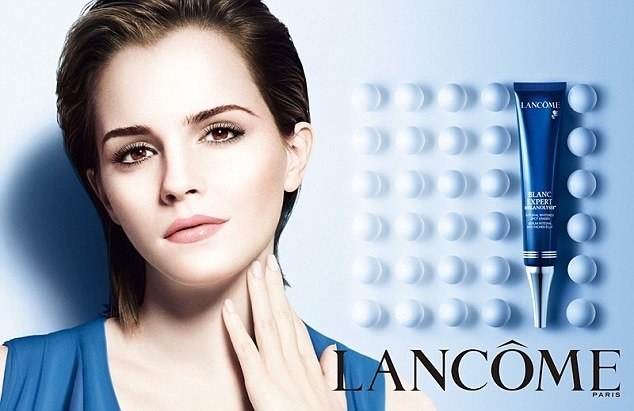

But the public controversies around marketing like this are sure to keep bubbling up: The internet has changed companies’ abilities to control their own message by region. The barrier between what’s sold in India and what’s sold in the US — and how — is far more permeable. Think back to 2016, when a Lancôme Blanc Expert ad campaign featuring Emma Watson went viral: Plenty of people on Facebook were furious that the actress was promoting what turned out to be a skin whitener. But the campaign featuring Watson — and to be clear, celebrities often don’t have control over the language used in different countries when they sign on for beauty campaigns — was specifically targeted to women in Asian countries. (Lancôme called the Blanc Expert range “the No. 1 whitening brand in Asia.”) The spillover when the campaign went viral in the US, five years after it initially launched, showed how tricky it can be for cosmetics companies to fully control their own messaging now.

L’Oréal Luxe (parent company of L’Oréal Paris, Vichy, Lancôme) and Neutrogena did not respond to multiple requests for comment for this story. Germany-based Beiersdorf (parent company of Eucerin, Labello, and Nivea) provided a comment through a third-party PR firm: “Beiersdorf is a global company with affiliates worldwide. Each affiliate operates independently and has different product offerings that are tailored to the needs of that specific market,” it said. “The products you referred to are not sold in Canada or the US. We take pride in creating products that promote beauty in all forms around the world.”

A Unilever spokesperson also provided BuzzFeed News with a statement via email. “We recognise that the marketing of these products has sometimes insinuated the notion that dark skin is undesirable,” it says. “We have strict marketing principles that explicitly state that we will not make any association between skin tone and a person’s achievement, potential or worth.” (Fair & Lovely, whose parent company is Unilever, features ads in which women become famous, men become more attractive to women, and everyone gets noticed for their looks.) “Our portfolio of brands is designed to respond to the diverse wishes of consumers around the world,” Unilever says. “Even-toned and lighter skin remains the most sought-after beauty desire across Asia and parts of Africa and Latin America.”

Indeed, Unilever and similar beauty companies sell these products largely because there’s still a market for them around the world. The availability of skin brightening products proves that whiteness is still considered the ideal. And the way advertising language in North America obscures this fact shows how unwilling North Americans are to acknowledge their participation in it. Companies like Nivea have been quick to apologize when an overseas ad is deemed racist in the US, but other than frustrated consumers on Twitter, there’s little internal discussion about the forces that led these companies to draft it to begin with.

The ethics of using brightening or lightening products are complicated, partly because even a product that simply protects your skin from the sun could, technically, be considered a lightener. “The threshold of what a skin lightener is is so low,” Rondilla says. “A sunscreen is a skin lightener; an antioxidant, something with vitamins A, E, and C, is a skin lightener. It forces us to think about what we are using and why we are using it.”

For most people who use cosmetics or skin care products daily, it would be impossible to eradicate the language or the history of whiteness as the ideal from our beautification routines. What may be now more important is determining what your intention is when you use a product. “I use my sunscreen every day because for me it’s about protection,” Rondilla says. “Are you perfecting or are you protecting?” ●