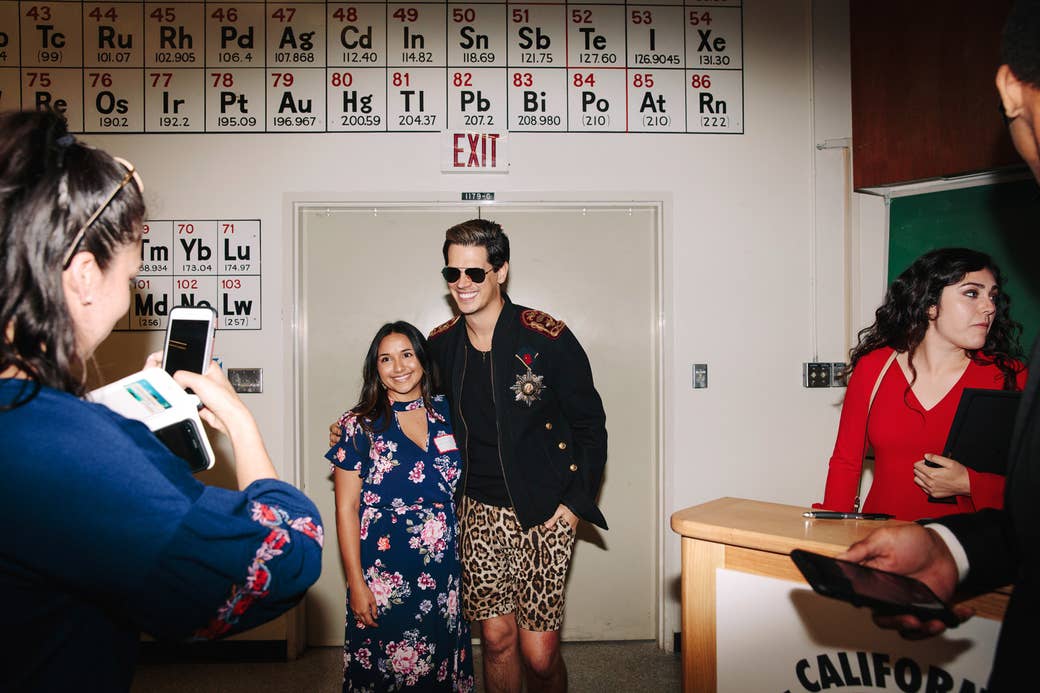

Shortly after 5 p.m. on a recent Saturday in April, the Chem 1179 lecture hall at the University of California, Santa Barbara, erupts in the kind of screaming you usually only hear when the headliner finally walks onstage at a concert. Coming down the right aisle of the auditorium is a man whose hair is highlighted with blonde streaks, in leopard-print shorts and a military-style jacket with red epaulettes, sunglasses still on (indoors), and diamond studs gleaming in his ears. The woman behind me turns the color of an anguished beet and screams his name: “Milo!!!”

Right-wing troll Milo Yiannopoulos has arrived as the surprise guest during the second day of this year’s California College Republicans Convention, where college Republicans from around the state are meeting for a weekend of speeches and drinking. The convention will conclude in a vote on the third day for a handful of leadership positions, including communications director, secretary, and the big one: chairperson. Today is mostly dedicated to students and guest speakers lecturing on “foes” in the liberal media (turns out it’s me!), the future of the GOP, and how to convince other millennials and Gen Z kids to become Republicans.

The mechanics of campus politics are rarely interesting. The stakes are low, the rules are complicated and tedious, and the impact of their elections is rarely explicitly seen or felt. But here the mood is more like a three-day prom, where it’s abundantly clear who’s popular, who’s not, and who’s going to be prom king or queen. And Yiannopoulos might have just nabbed that ultimate honor without even running for it.

Yiannopoulos begins greeting his audience, currently losing their fucking minds over him. The woman who screamed his name clasps her hands over her mouth and looks like she’s in physical pain, so much so that I have to ask if she’s happy or (as I naively imagined) upset. In response, she screams, “I’m happy, I’m happy! What the fuck! Oh my god, I don’t have my glasses on!”

You might be someone who thinks of Yiannopoulos, who was booed out of a bar in New York this week, as a defeated figure of the far-right. But here, he walks among the students like a high school quarterback who’s returned for homecoming, still the hero. Young women are literally weeping at the sight of him, boys are begging him for hugs and calling him “gorgeous.” One woman just wants to talk about free speech, telling him, “You should be able to say anything you want. You can’t say we’re for freedom of speech if you’re going to critique people for what they say.” Another takes a photo with him and screams, “I can’t wait to tell my parents I took a picture with a famous gay person!” A brown man with family in India praises Yiannopoulos for being “the only one” talking about “Islamist violence,” which isn’t the most uncomfortable thing to happen all weekend, but it’s certainly up there.

For most of the crowd, being in proximity to Yiannopoulos is the coolest fucking thing to ever happen. They love his type of politics: loud, ugly, self-serving, attention-grabbing, an approach in which a fierce attitude trumps any sort of discernible political policy. But for a small minority of college Republicans gathered here, this is their worst-case scenario.

For most of the crowd, being in proximity to Milo Yiannopoulos is the coolest fucking thing to ever happen.

“When you have people that are actively spewing hate speech, which he has the right to say, I just don’t think we should be the ones hosting it,” says Michael Gofman, a 20-year-old UC Davis student who is running for chair of the College Republicans this year. Gofman strikes me as the most polite man in the world, so this seems like the strongest language he could possibly muster. “I think he’s terrible. I think he’s bad for our party.”

For Gofman, Yiannopoulos is emblematic of the larger division within the California College Republicans, an “us versus them” problem: us, the reasonable Republicans who want to talk about the issues, versus them, the bombastic, loud, flashy winners. Yiannopoulos is a celebrity, and within the Republican Party of 2018, celebrity wins. Tomorrow, there’s an election to be held for the control of the party. A lot of the people attending think he doesn’t have much of a chance, but he’s still hopeful: “It’s too early to tell. It’s going to be too close to call.”

If the CCR Convention is prom, then Ariana Rowlands, a 21-year-old University of California, Irvine, student, is the queen. Rowlands, the biracial daughter of two immigrants, is immediately recognizable in any crowd at the convention — you just need to look for a thick wave of curly black hair amongst the largely white, largely male crowd. She is the incumbent chairperson of CCR, a close friend of Yiannopoulos, and the reason he’s made a surprise appearance; she’s also brought him to UC Irvine.

This term’s CCR convention is striking a similar tone to the last one, held in October 2017, where Rowlands won against incumbent Leesa Danzek. If you ask a Rowlands supporter about that election, they’d likely tell you Danzek was a rule-following, establishment cog. If you ask a Rowlands detractor, they’d likely tell you that Rowlands is an agent of chaos who’s more interested in disrupting the status quo than enacting any real policies. Rowlands’ victory was, depending on who you asked, either an upset or upsetting. (Danzek herself did not responded to multiple requests for comment.)

Since her initial win, Rowlands hasn’t spent much time on time-honored college Republican activities like student recruitment or door-knocking for state candidates ahead of the June 5 California primaries, in races which may prove incredibly important for Republicans trying to keep control of the real House of Representatives; that’s the kind of work that doesn’t get national media attention. (Rowlands says this is merely because thus far in her term, it’s been too early to focus on something like campaigning for the primaries.) Instead, her pet projects are issues like free speech, fighting a left-leaning media, and building a border wall. Rowlands is more focused on a Trump- (and Yiannopoulos-) inspired brand of political activism, one that spreads conservative ideas by generating agitprop, rather than worrying too much about policies or convincing moderates to vote Republican.

“These [students] are really told that they’re wrong, they’re bad people, they’re stupid, they’re racist for holding normal conservative beliefs,” Rowlands tells me on the first day of the convention. “They’re tired of it, they’re sick of it. This is us standing up and saying we’ve had enough.”

She posts photos of herself on Instagram holding guns, wearing MAGA apparel, and posing with Ann Coulter. (Caption: “Haters gonna hate. 🤗”) She’s been a guest on Fox News to talk about the War on Christmas on campuses and has written for Breitbart News. Just under a month before the convention, she posted a photo on Instagram at the border wall with Yiannopoulos. Rowlands has managed to frame the idea of being a far-right conservative as a kind of counterculture, trading on the appeal of flouting what’s typically expected of Californian college students by siding with the oldest, whitest, most establishment group you can think of.

CCR, and the way Rowlands guides it, matters to the Republican party on a state level. “Whenever anyone needs any sort of campaign help or volunteers or potential job applicants, we’re the first people that [the Republicans] come to,” Rowlands says. CCR members go door-knocking, canvas potential voters, and collect survey data about which side voters are leaning toward before an election. And this kind of campaigning is especially important for GOP candidates right now, as midterms across the country are turning out to be a battle even in the most entrenched Republican states. “They help make calls, they do a lot of the ground organization, they walk precincts, they do all the hard work,” says Matt Fleming, communications director for the California Republican Party. “To say what they do is ‘important’ almost diminishes what they do. We need them.”

Republicans in California, meanwhile, are trying to change the idea that their state is a foregone Democrat conclusion, even going so far as to propose splitting up the state. Trump himself recently tweeted that “there is a Revolution going on in California.” But the worry among some Republicans, namely the more moderate ones, is that the midterms will act as a repudiation of Trump and consequently all Republicans, making the California Democratic supermajority even harder to beat.

The conflict between the students here at CCR is a microcosm of a much larger one happening in the Republican Party itself.

To Rowlands’ opponent Michael Gofman, the way to shore up the GOP against a blue wave is not through protesting or posing with controversial conservative celebrities on Instagram. “We just want to come here and talk about the things we believe in and our vision for the California College Republicans, one that’s a lot more issue-based, and talking about policy,” he tells me. “What we can do to get people elected, and less being campus activists.”

Gofman is running on a slate called “Unite CCR” (Rowlands’ is “Rise CCR”; each slate has a number of candidates for different positions) and is a moderate in every sense: calm, gentle, and completely unassuming, were it not for his considerable height. If Rowlands is a bombastic, charismatic, galvanizing leader, Gofman is a consummate professional, the (young) adult in the room who never raises his voice, and thinks everyone could work together if they all just calmed down, followed the rules, and conducted things the way politicians used to, in the polite old days. Essentially, boring, deeply unsexy politics — exactly the kind of approach that doesn’t seem to work anymore in the post-Trump era.

The conflict bubbling within the California College Republicans between people like Rowlands and Gofman, and their respective slates, is similar to one we’re seeing nationally: Do Republican politicians need to be bold, unapologetic, and often wildly offensive, to be effective? Or should they return to the decorum and professional tenor formerly expected in politics? Should the right use the activism tactics more often employed by the left — which might mean more events like the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville (which ended in violence and one death) or the “free speech” rally held in Boston last year — to further their agenda, or should they focus on policy and campaigning? The conflict between the students here at CCR is a microcosm of a much larger one happening in the Republican Party itself.

After the speeches in the lecture hall are over, there’s a catered dinner set up outside under a tent with twinkle lights, where Yiannopoulos will be giving his surprise comments. While Rowlands sits at a table near the front with Yiannopoulos, Gofman idles near the side of the tent. He claps politely after the speech. He doesn’t want a photo.

While Rowlands is squarely in the now, doing what she can to make a splash — the Rise CCR Facebook page boasts that this year they “garnered more activity and press coverage than ever before” — Gofman is, at least in his view, trying to play a long game. “My goal is a Republican Party that’s inclusive and a big tent that houses all sorts of different people. When you’re talking about lesbians aren’t real or that all Muslims are terrorists, it’s not going to help make our party bigger,” he says. “If we start focusing on gender and race, all of those regressive things that we’re accusing the Democrats of using, then we really have no high ground.” The election, then, is a battle between decency in one corner and bombast in the other.

He’s definitely going to lose.

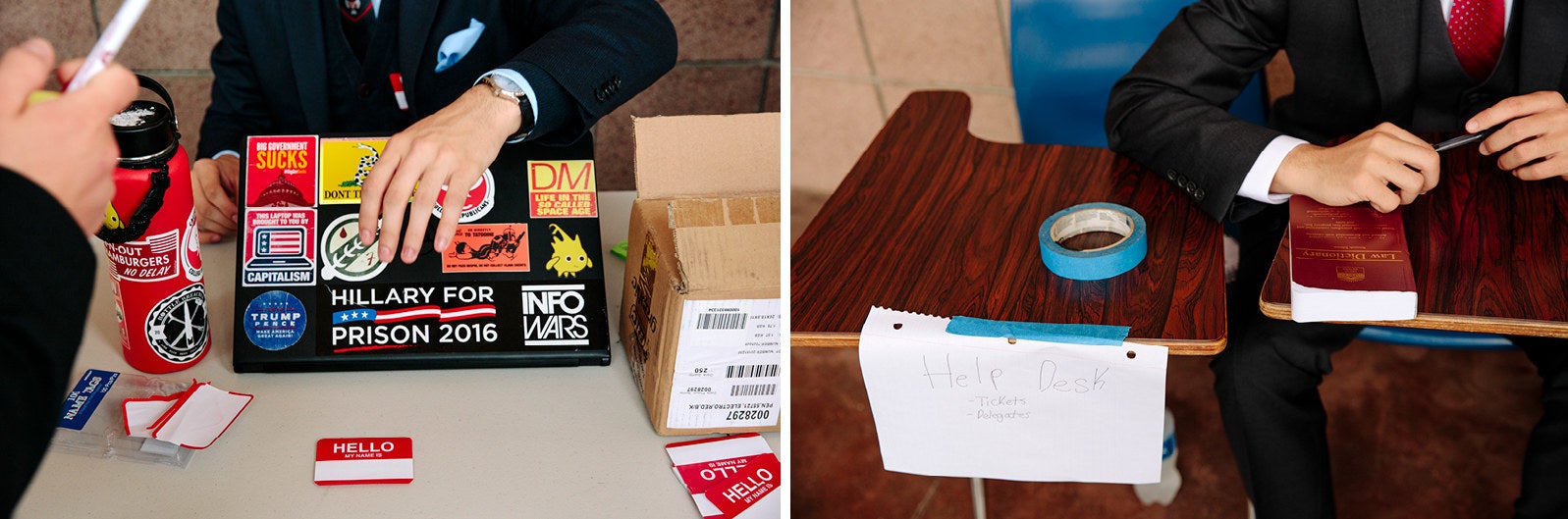

The afternoon before, the spring CCR convention kicked off with a casual welcome party at Goleta Beach Park, on the other end of campus, where 30 or so early attendees met up to drink Heineken in chilly weather. Rowlands was there in a one-piece Make America Great Again bathing suit, a California College Republicans flag draped over her shoulders (recently redesigned using the antifa colors), and white and gold Ivanka Trump–brand sneakers. Otherwise, it just looked like a bunch of college students on the beach, standing around drinking in their alma mater sweatshirts and listening to Drake. (Later in the weekend, they will combine their MAGA hats with suits and ties, alongside at least one Supreme/Louis Vuitton hoodie.) So, your average campus gathering, aside from the fact that everyone was talking about the scourge of socialism.

Rowlands often frames herself as an underdog, which is strange, because she’s the incumbent candidate with the loudest support of anyone here. “Sometimes she can be a little harsh with people,” said Dominick DiCesare, a 21-year-old UCSB student, a delegate, and a Rowlands supporter despite their minor disagreements. DiCesare, and most of the people hanging out at the park, felt like Rowlands represents a bigger, better, bolder direction all Republicans need to go in if they want the party to survive.

“Knocking on doors isn’t going to work. Activism works,” DiCesare said. “The left is going around and they have this high activism where they go march in protests and they make events and they videotape things. Why can’t we do the same?” The CCR gathering was briefly interrupted by a small crowd of men cheering on a guy who’s trying to chug a beer. (It takes a very long time.)

The chugger was Eric Lendrum, 23, a recent UCSB grad who’s returned just for the CCR festivities. “We are a tiny minority in the state right now. You have a split between conservatives, like, say, Travis Allan or Melissa Melendez, conservative populists versus establishment moderates like Chad Mayes, Arnold Schwarzenegger, saying, no, we need to go further left,” he said, “which just doesn’t work.”

Schwarzenegger in particular is a constant theme all weekend, touted as a model for the worst kind of Republican: a RINO, or Republican In Name Only. Most of the CRs here believe politicians like Schwarzenegger spend too much time trying to compromise with Democrats, their tone is too conciliatory, and their policies too left-leaning. Schwarzenegger is also one of the supporters of New Way California, a centrist advocacy group started by Mayes, which argues for a more moderate Republican party in the state in hopes of wooing independents and undecided voters. The CRs at Goleta Beach, echoing hard-line conservatives elsewhere, talk about Schwarzenegger as a traitor to the party, the very thing keeping Republicans from thriving.

Considering California’s current Democratic supermajority, the state might seem like an unlikely battleground for the soul of the Republican Party, at a college level or otherwise. But it’s more complicated than that. California was the birthplace of Jerry Falwell’s Moral Majority, the home base of alt-right media like Breitbart, and the state of origin for the Claremont Institute, the closest thing the Trump movement might have to an ideological center. Dotted across its blue expanse are long-standing pockets of conservatism such as Orange County, where last month the Board of Supervisors voted against California’s sanctuary laws. But California’s liberal gloss, combined with a student body who likely went to left-leaning high schools (or are currently going to left-leaning universities) means those students are now feeling politically alienated and ready to join forces with other students just like them.

California campuses are also a kind of ground zero for conservatives battling what they perceive as ideological censorship. In 2017, conflict erupted at the University of California, Berkeley, when staff and students announced they would be boycotting a series of appearances from right-wing speakers, including Coulter, Yiannopoulos, and Mike Cernovich. (The event was sneeringly called “Free Speech Week.”) Berkeley, though considered a deeply liberal campus, is being held up by right-wing activists and politicians as the most urgent example of free speech wars in America.

Trump has "really inspired a lot of people to speak up and not be afraid to speak their mind."

Michael Gofman’s slate, Unite CCR, is certainly more in line with Schwarzenegger’s approach than Yiannopoulos’s, but it’s tough to know what his exact policies are, since no one campaigning or running for Unite showed up to any social events on the first day of the convention. This weekend is a last-ditch effort to get out the vote for Unite, especially considering how likely a Rise (or Rowlands) victory feels. (Gofman will later tell me that their absence was because Unite representatives were campaigning elsewhere, but where exactly is never made clear.) Regardless, they don’t come to the beach for midday drinks, nor do they show up a few hours later to an empty and poorly lit parking lot next to the Courtyard by Marriott — as it happens, a Romney-connected franchise — for the “cigar social.” (They were supposed to have it on the Marriott property, but neglected to ask if they were allowed to smoke there. They were not.)

There’s a debate scheduled for Saturday between Rowlands and Gofman, but it seems unlikely it’ll happen because Rowlands says Unite, much like the administration previous to hers, is “afraid” to talk to her. “I think it’s because they don’t actually have any ideas,” Rowlands said. Either way, she didn’t seem worried; her missions are much bigger, taking conservatism further right and hoping to become the voice not just of aggrieved college students who feel voiceless in liberal-leaning institutions, but to affect that kind of change for the Republican party itself. “I think that the type of conservatism we’ve adopted within CCR, the bold and unapologetic conservatism, is the way forward for the Republican party,” she said, adding that Trump has “really inspired a lot of people to speak up and not be afraid to speak their mind.”

Gofman shows up on Saturday to the Chemistry auditorium on the UCSB campus, late, looking disoriented and clearly exhausted. He’s a consummate professional in khakis and a button-up shirt, with his mental state written across his face: Look, I’m trying, okay! He later revealed he had a final trick up his sleeve: a plan to combat widespread fear of Rowlands by introducing a motion for a secret ballot vote, instead of having delegates vote publicly, like they usually do. “Chapters have told me, ‘We will vote for you, all of us, if you get a secret ballot,’” he tells me later. “People are scared of her.”

“When you provide an alternative that’s loud, and bombastic, and incendiary, it gets people excited because it’s something different,” he tells me in reference to Rowlands. “We’re both dissuading the vote from us and we’re not getting that experience that’s going to help us in the real world.” Gofman is anxious about populist leaders with a cult of personality — he’s Jewish, and his parents come from the Soviet Union.

Rowlands takes the podium at the front of the auditorium for her welcome speech, wearing a bright red dress and looking gleeful. The speech is largely forgettable; the only people in the audience who show much of a reaction are Unite slate loyalists sitting in the back two rows. They don’t veer into full-on heckling, but are hissing insults about Rowlands to each other, looking at their phones to convey how bored they are, and muttering fact-checks under their breaths.

"She's definitely going to win. Everyone hates her, and she's going to win."

Gofman might be a mild-mannered voice of reason looking to work together, but his supporters are furious. They’re angry that people are allegedly removing themselves from the organization, that Rowlands personally threatens or screams at CCR members if they don’t vote her way (she has denied this), that there are allegedly high school students present at the convention to pad out the membership of college chapters, that complicated, niche constitutional rules within CCR are being broken, and that Rowlands has gone from being an outsider trying to break in, to being the establishment herself and running everything with an iron fist. They also allege that Rowlands’ temperament has made the California Republicans take a big step back from her. (Fleming, their communications director, denies this. “She certainly has a fiery personality,” he told me. “But like I said, a lot of people would call that enthusiasm.”)

“My biggest concern is it’s midterm elections time,” says Kavya Maddali, a 22-year-old St. Mary’s student. “We really need to be out there, getting the vote out.” Rowlands’ focus on activism, say most on the Unite slate, means there will be a lack of attention on helping state Republicans who are running for office.

“We have Republicans up north who are going to lose their seat this time around, and she’s not willing to send CRs up there to walk, knock on doors,” says Vanessa Mach, who’s running as cochair with Gofman. She thinks that Rowlands considers those candidates too moderate to be real Republicans. “We want to voice our concerns on getting politicians elected. She thinks activism will get people elected, which it won’t.”

To some, Rowlands’ focus on activism means she’s more than just a distraction: She’s an ideological enemy. “I would consider myself feverishly Republican, and I’m all about President Trump,” says Andrew Mendoza, 19, the CCR chair for UC Davis. “After the election, everyone was trying to paint it as if she was representing the Trump party. Honestly, she’s a Democrat. She operates as a Democrat.” Mendoza resents Rowlands for making the student government “centralized,” how she’s creating “fuckin’, like, a million committees” with no clear purpose. But, he admits, “She’s definitely going to win. Everyone hates her, and she’s going to win.”

After Rowlands’ speech, most of the Unite slate immediately stands up to go get brunch, hang out on the beach, and have a few drinks. What they miss is a day largely dedicated to speeches from people like David Blair, the national director of youth for Trump. He gives the crowd tips on how to recruit other students to become CRs — such as asking open-ended questions like, “Hey, what do you think of freedom?” — and how to deal with hostile recruitment targets who think all Republicans are fascists. (His advice: Forget them. “That is the person I am trying to beat. I’m not trying to recruit them. They’ll come around one day when they have a job, pay taxes, have a family.”)

And then there’s Shawn Steel, a lawyer and former chair for the California Republican Party. His talk focuses largely on the nightmare that California has become — his PowerPoint presentation includes a slide about how much human feces is found on the streets of San Francisco. (This is a pretty common Fox News report about how liberalism specifically is making California’s streets run brown.)

He’s also a big supporter of Rowlands, and the one who provided cigars for the cigar social in the parking lot. After his speech, Steel talks to me about Rowlands while we walk to a nearby Starbucks during the lunch break.

“I think she’s terribly important,” he says. “The left doesn’t know what to do with her. She’s good-looking, she’s articulate, she’s Hispanic, they’re just befuddled. In a way, it’s Trumpian. She broke the eggs, unsettled a lot of people. She is actually a new force in Republican politics.” Steel tells me this while asking the barista at Starbucks for a cold cup and a pen so he can write his own order down: Grande Frappuccino, no base, three pumps, non-fat milk three quarters of the way, packed with ice, blended, with a triple espresso on the side, two-thirds decaf, which he then pours into the finished Frappuccino.

While Steel sips on his very confusing and sad Frappuccino, he asks me about the “ethnic origins” of my name, which I tell him is from Kashmir. When he asks about my family’s religious background, and I tell him we’re Hindu, he lights up. “Oh,” he says. “You are definitely an outsider’s outsider.” Then he tells me about a calendar he has that marks “all the great conflicts of radical Islam’s defeats.”

Eventually, I manage to extract myself from the conversation, but not before a few parting words from Steel. "Bless your soul," he says.

The open mic period on Saturday, which closes out the events leading up to the finale dinner, is mostly filled with people cheering on Rise and, more generally, America. (One student reads from a prepared speech, “How do you define the American nation? In my search, I found that you can find America on every horse ranch, and every rodeo, it is rhythm and blues and rock and roll.” If there’s anything more Caucasian than calling R&B “rhythm and blues” I, in my search, have not yet found it.) But while two men are giving an unprompted lesson on how to dress for success as a Republican (shoes match your belt, French cuffs means you’ve levelled up), Yiannopoulos appears and literally steals the show.

While his adult-world influence may have waned, Yiannopoulos possesses a most potent form of political power in his ability to repurpose the same activist tactics that liberals traditionally use to pull people together. He has a clear list of enemies: liberals, feminists, academics, people of color. Though, he doesn’t think he’s a racist. "The reason people get upset with me is because I'm effective. And funny. I don't have opinions that aren't shared by a million Americans. I don't say anything outrageous. I'm not a racist, I'm not a sexist, I'm not an outrageous terrible person, I just don't mind who gets upset. To be more upset about humor than you are about actual real beliefs and policies is fucked up." His tactics, just like Rowlands’, though, are all about creating commotion, then using that mess to create solidarity. (Rowlands says Yiannopoulos financed his own trip to CCR; Yiannopoulos makes a quip during his dinner speech about how he’s “between billionaires right now” and that his speech has to be short since it’s unpaid.)

And it’s working. When Yiannopoulos appears, you can see Gofman and the other Unite delegates — even if they’re wholly starstruck — immediately deflate. How do you beat the woman who brings Milo Yiannopoulos, a verified famous person, up close and personal to all these students? How do you campaign against celebrity? How do you even come back to the dry, process-oriented nature of the convention after Milo Yiannopoulos shows up to have dinner and, later, to go dancing with you? If the odds of Gofman’s secret-ballot maneuver making an upset possible were long before, they seem even longer now.

After the final vote one student pushes my recorder into my chest, telling me, "You got your Marxist, third-world, shithole policies!"

Yiannopoulos gives a brief speech to the still-hungry crowd about how they need to come together as one, instead of splintering off into too-small subgroups. “You’re facing an enemy that owns, controls, operates every branch of civil society and much of the government. And you’re behaving like children. Snap the fuck out of it,” he says to applause. “You guys need to be working together. You have one generation left to fix this. Up to you if you’re going to do it.” It could seem, maybe, like a message of unity, if “unity” means siding with the biggest and loudest person on the playground.

“Whether or not your chosen slice or faction — or, as it seems to be the case, splinter — is currently incumbent, effective organizations require discipline, leadership, and respect,” he tells them. “I don’t see much of that here. That’s a shame, because it makes all of you ineffective.” Everyone, including those on the Unite slate, clap as loud as they can, their eyes glassy and full of admiration.

Maddali, an Indian immigrant who has spent most of the weekend openly deriding Rowlands and her political methods, is now begging Yiannopoulos for a photo after his speech. She’s holding her phone to her chest like a blessed medallion.

“Do I believe a lot of his ideology? Absolutely not,” she says, citing his rampant anti-Muslim sentiment. “I wanted a photo. I’m not going to lie about that. ”

Despite considering most of the mainstream media unethical, Yiannopoulos is more than happy to talk to me after the pandemonium in the auditorium settles down. Back when he was still on Twitter he once incited his followers to harass me because of a tweet he didn't like — but he doesn't seem to remember my name. He does, though, recognize the name BuzzFeed. “Oh, BuzzFeed is cancerous,” he says, referring, perhaps, to our reporting that helped collapse his book deal and expose his white nationalist connections. “Just outright dishonest.”

Later in his speech, he calls me “perfectly nice” before calling BuzzFeed “fucking garbage.” (This isn’t the first time someone publicly mocks me and my profession at the convention, or the last: After the final vote, one student from California Polytechnic State University pushes my recorder into my chest, telling me, “You got your Marxist, third-world, shithole policies.” A PR tip, from a media professional: Don’t fucking touch me!)

Yiannopoulos talks at great length, about a diverse range of topics, from the fact that he’s met Mariah Carey to his belief that “civil war is unavoidable” to his personal victory of “ending” feminism. Eventually, he gets around to talking about Rowlands.

“I just love her. I think she’s great,” he says. “She’s got this instinctive, sophisticated understanding that if you pander to people who are dedicated to your annihilation, you’re not going to persuade moderates. I can recognize star power when I see it. I have it. She has a little star power in her. She has potential.”

“This is so fucking triggering, dude.”

Elias Rodriguez, a 21-year-old UCLA student, mutters this under his breath right before the vote officially starts on the final day. After dinner and Yiannopolous’ surprise appearance the day before, most of the attendees headed over to Velvet Jones, a nightclub in downtown Santa Barbara, where everyone got very drunk, danced to Flo Rida in a very horny way, and chanted “USA! USA! USA!” over “Mi Gente.” Consequently, today, everyone is hungover, a little exhausted, and extremely annoyed.

“This is what CRs have become,” he grumbles, resting his feet on the row of chairs in front of him in the second-last row of Chem 1179, sulking. “A bunch of neckbeard assholes. They don’t give a shit about American values. I just want Ari to lose and go party and have a good-ass time.”

The election, like most of the convention’s events, starts an hour late and takes hours to happen. Mendoza, the UC Davis student who called Rowlands a Democrat, quietly tosses a few empty champagne bottles in the trash outside the auditorium before the vote begins. “My delegation needed motivation to sit through this,” he says, smiling. “It’s my duty as chair!”

The vote is what you’d expect from campus politics or, frankly, democracy generally speaking: messy. Half the crowd is taking it far too seriously (parliamentarian Kimo Gandall keeps yelling, “Sir, you are out of order!” to anyone who talks without being called on; eventually people try to vote to remove him, which fails) and the other half is treating it like a complete joke (“I’m voting on whoever will annoy me the least,” says one man in the gallery).

Gofman introduces the motion for a secret ballot, the big swing he was preparing for all weekend. This could change everything. There’s a scattering of support voiced, some from people who aren’t members of the very vocal Unite faction. Gofman refuses to admit defeat against Rowlands until he absolutely has to.

But, of course, he has to. The secret ballot doesn’t happen, and he loses the vote for chairperson. It’s not even close. It was never close. Unite loses every vote, for every representative, except for one.

“This is democracy now,” Vincent Wetzel, 24, says to comfort Rodriguez. “These are the rules we have to play by.” He tells everyone to shake hands with the victors.

"They don't give a shit about American values. I just want Ari to lose and go party and have a good-ass time."

Gofman relaxes immediately once he loses. His posture loosens, his chest doesn’t seem filled with cement, and he actually sits down with me instead of shuffling from foot to foot. Once he comes down to earth, you can see the little American flag cufflinks he’s wearing.

“We thought we could get a secret ballot,” he says, shrugging. “I didn’t know if I could win, but I at least wanted to offer people an option, one that most people didn’t take. I really hope [Rowlands] takes this challenge as a message that people are dissatisfied with what she’s doing. This group of people does not want me representing them. It bums me out, but I understand why.”

In the three weeks since winning the election, Rowlands has been more vocal about deployments and door-knocking ahead of the state primary, posting a few times on Facebook and Instagram encouraging people to campaign for people like Bonnie Gore, who’s running for Placer County supervisor, and Justin Fareed, who’s running for Congress. (This week, Rowlands has been posting photos of herself door-knocking for Mimi Walters.) But still, her bread and butter is in aggressive activism. She’s been spending the last week defending the UC Merced College Republicans, who claim they were harassed and falsely accused of spreading hate after they set up a table encouraging people to call ICE on their undocumented classmates. “We can, and will, keep all legal options on the table,” Rowlands wrote on Facebook.

The myth many moderates and liberals have told themselves, especially since Trump’s election, is that, if they wait long enough, hard-line conservatives will literally die out. But young people like Rowlands and her supporters are a testament to how wishful that thinking is. They’re already spreading their views (and getting thousands of Instagram followers for them), and in a decade — maybe less — they will have moved on from campus politics into bigger things, the kind that might directly affect everyone in the country. They could become their generation’s Donald Trumps or Steve Bannons or Milo Yiannopouloses. Rowlands, I’m sure, will take this as a compliment to her longevity and her influence, which on some level it is. But so far, she and people like her only have volume. And maybe, at some point in the future, that won’t be enough anymore.

A few hours after the convention ends, I make my way to a Jack in the Box across the street from my hotel room to eat the Spicy Chicken Sandwich I promised myself when this was all over. As I walk by a gas station, Michael Gofman pulls up to fill up his car for the drive home. He no longer looks like a politician, instead wearing a T-shirt, like some kind of college hooligan. When he sees me, he gives me a small wave and I wave back. Seeing him like this fills me with pathos, and then relief. Maybe it was better he didn’t win. Those people never deserved him. ●