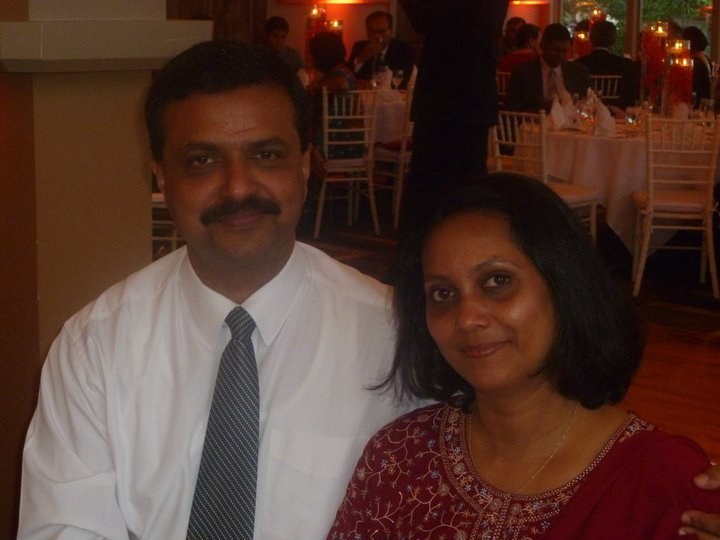

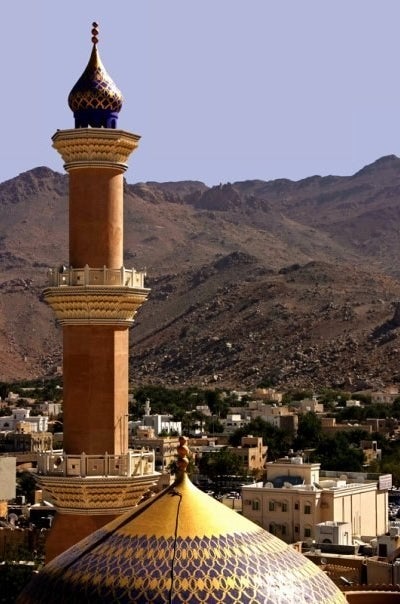

When we arrive in North America, I have never yet crossed a street by myself. I’ve spent the last 14 years in Oman, a sliver of the New Middle East where, for all its malls and modernity, transit as a girl meant being driven in a car by my mom or walking in blistering heat holding my father’s hand. I am two weeks past my 16th birthday, but as my boots slip and slide on icy asphalt, it feels like learning how to walk all over again.

The coats we bought in Oman are laughable, unlined scraps of wool and corduroy that the wind tears at like a Rottweiler. The temperature on the 22-minute walk to the Indian Embassy is -9°C, which is 17°F, which is about 73 degrees colder than anywhere I have lived in my short life. I instantly re-evaluate my Judeo-Christian conception of hell as a hot place.

My father’s ears are visible in the distance, an angry boiled red. Eyes watering from the cold, I think, I can’t go on, I can’t, I’m going to die, I can’t do this, but we have 10 more blocks to go before we can be anywhere warm, so I suck it up, which is an American phrase that means I must do the thing I think I cannot do. I walk faster and faster, overtaking even my dad, and cross my first street at an almost-run, half expecting traffic to roll my body into cartoon flatness, my heart juddering like mad.

The first night in America, I look up restaurants to get dinner from, and decide on a place called Chipotle. I see the people in line behind my dad flip their eyes upward as he strains to understand the menu, how it all works. It is the era of Bush junior, of men who look like my father getting stopped and questioned for two hours when they attempt to travel by airline, of women who look like my mother getting ignored by the sales assistants at J.C. Penney when they try to buy real winter coats.

Back at the apartment, we sit cross-legged on rental carpet and share the food — burrito bowls, they’re called. They are delicious. My back is to the radiator, and I feel warm and full, and happy that we have one another.

On my first day of high school in Palatine, Illinois, I can’t figure out my locker. American teenagers fill me with fear. These creatures my own age, allegedly, but bleached and lip-glossed and wearing clothing that fits so differently from my own, occupy space with such force and ease. I am a little turtle with my brown face and overstuffed backpack, swerving to avoid my classmates in the hallway.

I’m asked, "Do they have, like, schools where you come from? Do they have malls? Is Oman, like, a village in India?" I spend most of my lunch hour on that first day trying to explain my visa status, my legitimacy in pursuing public education. I’ve rehearsed the speech with my parents ad nauseam, so I know the jumble of letters almost by heart. My family and I am here under H-4 visa status, as dependents on my father’s work visa. We applied for our green cards, hopefully we’ll get them soon.

I try a thing called tater tots. I get a C- on my test in English, which was always my best subject before, and a hard lump begins to form in my throat. At the day’s end, a kind boy (Chinese-American, first generation) helps me open up my locker. I take the bus home, exhausted by the day’s trials, crossing streets like I’ve done it all my life.

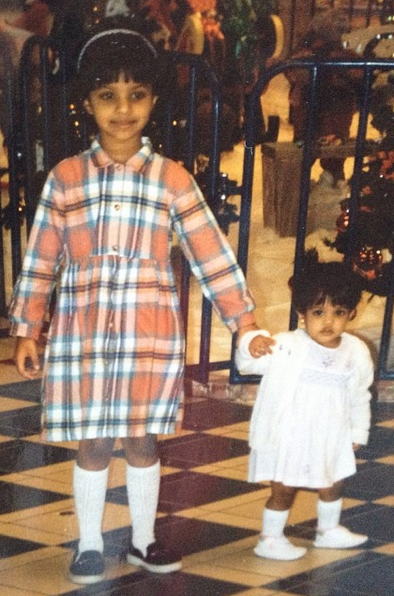

My father, who had a job in Oman where he was beloved by superiors and subordinates alike, can’t connect with his co-workers. For the first time he isn’t bringing in business, and starts worrying about losing his job — the job all of us are dependent on for visas. My sister and I skulk around the house. Sometimes she bursts into tears at random, inopportune moments, refuses to explain why. My mom and I ask her if she is getting bullied at school; she says no, and I can’t tell if she is lying. Our individual pain makes us all opaque to each other.

Our first Thanksgiving passes us by. We eat a modest, untraditional meal, just the four of us. No turkey. We are thankful for one another and for a roof over our heads. We are quiet. This cold, wide country has stretched us all out to a thinness.

My mother, who cannot teach or work as a dependent on a work visa, stays at home all the long winter months. She stares at her ESL textbooks gathering dust and says, “Maybe we never should have come.”

“Maybe we should go back,” she adds, and I, who have spent my entire life speaking with respect and deference to my parents, explode with incoherent rage.

There is a before to immigration; not all of you dies to be reincarnated in the new country.

A couple of hours later, my dad tries to make me come out of the bathroom, where I have fortressed myself, and apologize. I refuse.

“Do you know why we came here?!” he bellows at me through the sliver of open door. “Do you know the kinds of lives Amma and I had? Great jobs, good salaries, our own people all around us! Do you know why we are sacrificing? For you! To get an education in good schools, for a change, for you both to go to college in America! All of this, this has been for you!”

The words dissolve me into quiet, fill my head with darkness. There is a before to immigration; not all of you dies to be reincarnated in the new country. The old life, good and bad, rattles inside you like broken gadgetry. Family, careers, beach picnics with lifelong friends, knowing we belonged, the ritual of shopping and shawarma: These are things my family and I have left and will never get back. Because my parents want their daughters to get a good education, to be respected as equals, and to be able to walk down a street by themselves without fear.

And so, humbled, I decide: I will make good. I try to catch up to the American system, these classes that my sister and I joined in the middle of the school year. I argue with my guidance counselor when she tries to dissuade me from taking Advanced Placement classes. I study how other girls dress and beg for an allowance, car rides to Woodfield Mall. I learn to fill in Scantron bubbles correctly, to kiss boys while preventing them from moving their lips below my collarbone.

When a girl in my history class hears my accent — with its long A’s, its medley of British-, Indian-, and Arab-tinged English — when she hears my articulation of the word "can't" as "cunt" and chews me out for it, I make my first, angry choice to become more American. If I get taken more seriously with a nasal Midwestern accent, I decide, I will cultivate one. We start going to a mega-church. I find the spectacle and Jesus rock distasteful, but am warmed by the kindness church folks show my parents, their Indian accents and brown skin notwithstanding. It’s kindness that seems out of place in the frosty northwest suburbs of Chicago, where I frequently see chinos and Chico’s–appareled folks skate their eyes over my mother and father with curiosity or disdain.

But I betray my parents in small ways, too. I get a boyfriend. I make friends with the stoners and baby goths as well as the AP kids. I join after-class things. I tell my parents I’m at after-class things when I’m actually with the boyfriend. The accent is natural now.

I ride in a friend’s red car, speeding through beautiful, manicured suburbia with duck ponds and stone houses, the wind flipping through my hair, and in that moment, I feel unutterably happy and free for the first time in so long. I remember my cloistered, shuttered life in Oman, and think, This is America like all the movies and I’m here, I’m here.

In my living room, a few months shy of 18, I watch the television as a man walks up to a podium in Grant Park and says, “My fellow citizens, I stand before you.” I’m shooed out of the room, I’m weeping that hard. From the doorway, clutching my ribcage and breathing in small gasps, I watch this black man with a white mother, who grew up in Hawaii and Indonesia, whose name is fucking Barack, take the oath to become president of the United States, and joy and disbelief make stars and constellations within me.

Maybe, just maybe, I’ve underestimated America.

I cross my fingers for the green card, my permanent residentship status, to arrive before college starts, so I can possibly get in-state tuition or financial aid. We’ve been here for years, after all, paying our fair share of taxes.

It doesn’t arrive. I get accepted to college, as an international student. I go.

Madison, Wisconsin, where I have made my choice to stay for the next four years, is a slender, beautiful isthmus whiter than its winter snow. I still can’t work and get paid because of my visa, and I always feel aware that money is tight at home, with my college tuition, the accelerated mortgage, the lawyer’s fees for the green card, the one salary. It stings when my college friends make quips about me obviously shopping only in the sales section. I say nothing when a white friend talks about going to an Alpha Kappa Alpha party where there were only folks of color, and how uncomfortable it felt to be the only white person in a room.

I confide my fears — of having nothing on my resume when I graduate, of deportation, of the general precariousness of having my whole family’s presence in this country contingent on my dad’s job — to my best friend as we stagger out of a house party. He gets down on one knee in the lobby and says, “If you need a lavender marriage to stay in this country, Sarah Mathews, I’m your man.” The sweetness of that memory is something I savor for years.

I take classes. I scour web directories for scholarships I might actually be eligible for. I try a thing called a Twinkie. I learn to ride a bike. I fall in love.

I am inching up on 21 now, and my parents grow worried about what will happen to my visa status when I get there. Go see your university’s international affairs office and ask, my dad tells me. Worst-case scenario, you can transfer to a student visa, he says. In the international affairs office, I am told by a nice Midwestern lady that I cannot be a dependent past 21, and because my family filed for a permanent residentship, which indicates intent to stay, I likely will be denied a student visa.

"But what does that MEAN?" I ask, air painful in my lungs. "You should talk to a lawyer," the lady says. "They’ll know more than me, but it means you probably can’t stay here in the U.S. after you turn 21." My world goes inky black and screeches to a halt.

“But you’re here,” a friend says, disbelievingly, over terrible, rock-like bagels. “You’ve been here. You’re not an — illegal. You’ve been here for years.”

Twenty-three days before my dreaded 21st birthday, I get the notification that my family’s application has progressed to the final step, that they’ve opened the quota to include my priority date. In English: I’m getting authorized to work, and the green cards are coming. In three months. Three. Months. The word joy becomes a failure of language.

The cost for all four of us, just to do our medical checkups and have the lawyers submit them, is 25,000 American dollars, not coverable by insurance.

Two and a half months later, I’m deeply unprepared for the headspin and heartbreak of the notification in the latest immigration bulletin, which says that the government has “retrogressed the priority date.”

"But what does that mean?" I sob over the phone to my parents.

Visa retrogression means the government closes the quota of waiting immigrants that was opened earlier. No more green cards, until they see fit. But here’s the pewter lining: The authorization to work came through, giving me the right to live and work for pay in this country for one and a half years more, with the slender possibility of renewal. I am lucky, really. Relatively speaking.

At the marrow of it, it is really my relative luckiness that rusts my soul, makes me pissing-on-the-subway levels of crazy. The unbelonging and the uncertainty never quite stop aching, but I have a college education, am now able to work, and my family is here with me. I have the humility to realize how that stacks up against large swaths of the rest of this country’s immigrants, against those who are desperate to come in, against the kids from South and Central America riding the roofs of trains into this country to try to find their mothers, wearing shirts that read I HAVE AIDS to keep from getting raped.

At the marrow of it, it is really my relative luckiness that rusts my soul, makes me pissing-on-the-subway levels of crazy.

So I keep living my life. Luckiness dogs me. I always feel a tenderness toward middle-aged men who drive cabs because I see my father in them, and see his possible fate. I call them "Uncle" or "Sir," and ask how they are. They tell me about talking to their families once a week; they talk about their jobs in the old country as doctors or engineers or business owners. They tell me about learning to make good.

My family is invited to Thanksgiving dinner by the neighbors down the block, the first time it’s not just the four of us. We say grace over the beautiful, excessive meal together, white and brown faces alternating around the table.

We watch the turkeys being pardoned on TV. I’ve never heard of such a thing. My neighbors explain it: There are two turkeys that compete, Caramel and Popcorn, and both are pardoned by the president, and get to live on an estate in Mount Vernon.

My dad jokes, "But what about the turkeys on tables all over the U.S., the turkey we just ate?"

I am walking around Madison talking politics with a friend who says, "We can’t have amnesty because all these people just need to learn to come here legally," and I laugh so hard, so scornfully, that I slip on the steps of the state capitol and crack my face open on the sidewalk.

I move to Washington, D.C. Three of my friends from before America make a trip to visit me. Together, we take selfies in front of the White House, the Washington Monument (“The Bill Clinton monument,” my friend Karn corrects me), and the Lincoln Memorial. At that final stop, I stand before the momentous effigy of the American president I admire the most, and we read the carved words together.

Tears suddenly melt their way down my face, surprising me, alarming my friends. I don’t try to explain, really. It’s the beauty of the ideals Lincoln wrote about and the potholed road of the reality leading toward them. It’s because I realize that I love this country deeply, even though it has never loved me back.

Seventeen days later, I walk out of a bar and check my phone to see my dad’s missed call from three hours ago, to see this text from my sister: "Oh my god. call home."

My mind stops. It jumps to death, cars smashing into bone, every health problem in my family’s history extrapolated to its fatal conclusion. I call. My father answers.

Three minutes and 17 seconds later, I hang up and stagger into an alley between Q Street and Corcoran. My back against a brick wall, I stare up into the sky, for once beyond tears.

The green cards have come. Eight years in waiting. None of us, in all the years and mythic significance that they’ve attained, ever thought to ask what they looked like. It is a beautiful literalism. They’re pieces of plastic. They really are green. Go figure.

I go home and tell the old friend who proposed to me in the lobby those six years ago that he’s off the hook.

No one really seems to get it. Oh, cool! That’s great! It is anticlimactic, I suppose. I’ve been here for years, performing and earning America. Most folks I know now assume I’m a hyphenated native, a true-blue American-Born-Confused-Desi, versus a tenuous extra who might have to leave any moment. One of my more thoughtful friends asks me, "How does it feel?"

It feels like running across a busy street out of the cold, into the sudden shock of warmth and safety. It feels like winning the lottery. The lottery is to have a seat at the table, but unless you avert your eyes, you still see the masses who have also fought to make it in, their faces pressed to the glass as they watch you bring the food to your lips. You know you’re no better than anyone out there, have done close to nothing different, but they are outside and you are in.

How does it feel? It feels like you’re a pardoned turkey. You are one of the fewest few, one of those who get to keep the life they have built. Look around at your life, at the scaffolding of routine, the gray couch that you saved for, the business you’re working to start, the living room you painted that precise shade of Sherwin-Williams yellow, the faces you kiss goodnight. It is that simplest luxury: You get to not be uprooted, at any moment, from all of that.

On a crisp winter night in D.C., the year I get my green card, President Obama announces his executive action on immigration. I listen to bar conversations devolve into predictably partisan chatter. I hear the old refrain, couched in more sophisticated, wonkish phrasing: These people just need to learn how to come here legally.

And after all these years of alternating between stoicism and hope, I am so angry. I’m grateful for my reprieve and for my family’s, but filled with a retroactive, reverberating fury at the broken system.

I’m furious because true justice is something greater than pardoning turkeys.

I’m furious because true justice is something greater than pardoning turkeys. It is more expansive than letting the odd exception pass through a thicket of expensive bureaucracy and codified racism, and hailing the lucky, made-it-with-an-inch-to-spare few as emblematic of the system working.

In February 2015, the government was still processing some family-related visa applications filed as far back as August 1991. It was still processing some employment-related visa applications from December 2003. We have applicants in the system who have been waiting for legal permanent resident status for more than 20 years. Many of them are already in the U.S., paying taxes, and contributing to our economy in a multitude of ways. And yet President Obama’s executive action to protect undocumented immigrants from deportation has just been delayed by a court ruling, again. The setbacks never end.

Our national focus on undocumented immigrants is, at its heart, about the creation of common enemies. It’s about cultivating fear of those who are new, different, or vulnerable, for political gain. Who would choose to be undocumented if the legal system were less capricious, less rigged for those with luck and money? Who would choose to risk everything if there were another way?

When I see xenophobes decry the people who have fought to make it in, when I overhear “You’re in America! Speak English!”, when I listen to “These people just need to come here legally,” I think about the immigrants and the children of immigrants I have known through the years, documented and not. I long to grab collars, pull faces close to mine and say, “These people are more American than you will ever be.”

Because when you perform the act of audacity that is consolidating an entire life into a couple of suitcases and striking out to make your way, what is not American about that? When you leave the old country so that your daughters can have a good education and walk down their streets without fear, what is not American about that? When you flee violence and poverty to come to a land of plenty, when you are willing to learn new languages, to haul ass, to do twice as much work, what is not American about that?

To cross borders, to brave tribulation, to hustle, and to take up the new life is as American as apple pie, as beer, as Google, and as jazz. It is also the process by which all these things came to be American in the first place.

Immigrants are all around us. They drive us to airports. They take our temperatures. They teach our children, they invent pieces of our future, they start our businesses, and they get our orders right. Our nation’s adopted sons and daughters have every right to sit at the table, to partake in the meal that they themselves helped prepare. There is more than enough food for everyone.

My mother finally has a job again, my father is doing well at work, and my sister has started her second year of college. I call home; my father is watching Obama speak on TV. My whole upbringing, my parents have harbored a Puritan zeal against compliments, but sometimes my father dreams outsize dreams for me; he tells me that he hopes I’ll publish a great novel or start my own company.

Two glasses of red deep, he says, “If you had been born here, maybe you could have been president.”

I laugh loudly. My mom scolds him, “Don’t be idiotic.”

He continues, undeterred. “It’s OK. Maybe you can become secretary of education. Or win a Pulitzer.”

For once, I don’t contradict him. The chance to stay is, at the heart of it, the gift of freedom to dream. To build, to give to others, to say, "I, too, am worthy. I, too, am America."

I say, “Yes, maybe.”