How does a woman turn from a mortal to an icon overnight? Think of Pamela Anderson, in a tight Labatt Blue shirt, at a football game with her friends, and finding herself featured on the stadium jumbotron long enough for the crowd — and later the world — to fall in love with her. Or 16-year-old Judy Turner, cutting class at Hollywood High School, going to a soda fountain, and being “discovered” as Lana — “discovered” being the operative word.

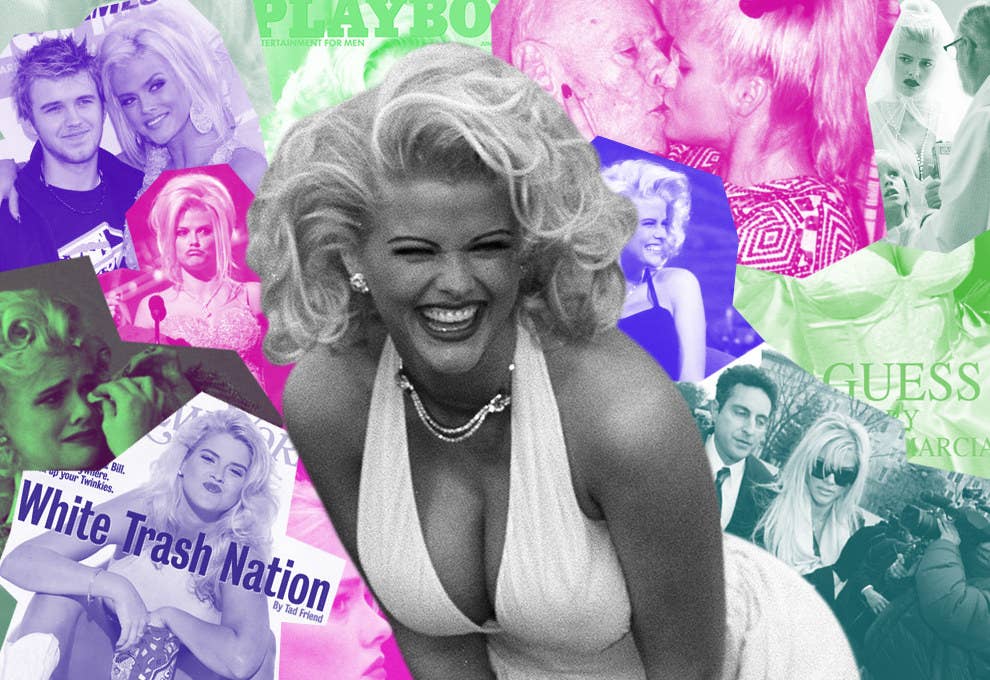

For the Hollywood origin stories we know to be satisfying, the heroine in question must have no idea she is worthy of such attention until she is suddenly rescued from obscurity. Especially if she is to be remade as America’s next great sex symbol — as Anna Nicole Smith was in 1993, when she suddenly saturated American media, appearing on magazine covers, billboards, and screens of all kinds, and found herself touted as her decade’s Marilyn Monroe.

If the heroine's allure is the product of not just blind luck but sustained effort and intent — let alone strategic surgical alteration and courtship of wealthy benefactors, as Anna Nicole Smith’s was — then she is too powerful to remain sympathetic, and becomes an object of jealousy, rather than aspiration. It’s one thing to be chosen as a goddess; it’s quite another to claw your way to the top of Mount Olympus. And when the public finds out a goddess is in fact a striving mortal, this revelation will push her into a very different kind of myth: one whose satisfying conclusion comes not when a woman is exalted, but when she is destroyed.

From 1992, when she made her first appearance in Playboy, to her death on Feb. 8, 2007, Anna Nicole Smith occupied the story of the beautiful girl lifted up from the dust, and then the story of the beautiful woman destroyed, and sometimes both. “From the moment Anna Nicole got famous,” reporter Mimi Swartz later wrote in Texas Monthly, “she told the world that her role model was Marilyn Monroe. It was a shrewd move, as it linked her image with one of the greatest American icons of all time, and it had a neat logic: one platinum-haired sex symbol taking after another, one poor, deprived child latching onto the success of another.”

Anna Nicole Smith first rose to celebrity as a dirt-poor single mother from Mexia, Texas, who went from rags to riches after being discovered by Playboy when she went to an open call for models at a boyfriend’s urging. (“She was the most beautiful girl I had ever seen without makeup,” the magazine’s photography editor, Marilyn Grabowski, who had been casting the magazine’s centerfolds since 1964, said at the time. “Sharon Stone is a close second.”) Then, just as suddenly, her 1994 wedding at the age of 26 to 89-year-old Houston oil tycoon J. Howard Marshall made her a national punchline. A year later, he would be dead, and Anna would eventually find herself in a Supreme Court legal battle with his children for her inheritance, spearheaded by his son Pierce.

By the time the case had finally been conclusively adjudicated in 2011, Pierce Marshall was dead, Anna Nicole Smith was dead, and whatever power she had once held, real or imagined, was gone with her. Her infiltration of the American consciousness had come in two distinct waves: first with her rise as the Marilyn Monroe of the 1990s, and then with her presence as a reliable staple of the early-2000s reality TV–fueled celebrity shame machine.

But before she became infamous for being a gold digger or a cable news fixture or an emblem of the “galloping sleaze” of “white-trash behavior” that Tad Friend warned readers about in a New York magazine cover story that featured her as its mascot, Anna Nicole Smith was a star. America had fallen in love with her — that love which is the particular species of cultural obsession our country reserves for buxom white blondes — but it was a love she could not sustain if she revealed herself to be any more complex than her centerfold image. It was a love that could not diminish, only reverse, and now it had transformed into derision and hatred. Yet no matter how hard Americans tried to regard Anna Nicole Smith with apathetic dismissal, they couldn’t hide their fascination — and still can’t. Why? Was she just another model, another B-lister, another early casualty of reality TV? Or did she show us something about ourselves, about our country, that frightened us more deeply than we could ever admit?

“Anna Nicole Smith” was a fantasy. She made herself into one, and America accepted her in fantasy form. Yet even when her humanity — and her weakness — was visible for all to see, and the hard realities around which she had constructed this fantasy version of herself became extraordinarily painful, we remained determined to see her as unstoppably seductive, manipulative, glamorous, and unforgivably larger than life.

In the first minutes of Playboy’s 1993 Video Centerfold, a 35-minute compilation of Anna Nicole Smith telling the viewer about her life and posing in a series of softcore scenarios (taking a bubble bath, rolling around in satin sheets, eating a slice of cherry pie in a roadside diner), residents of Anna’s hometown of Mexia, Texas, share their reminiscences of the girl they had once known as Vickie Lynn Hogan.

“She was a homely child,” one local says.

“She was very shy, growin’ up,” says a snaggletoothed man leaning on a wooden fence.

“She used to be built like a boy,” a woman adds.

“I wasn’t very popular in high school,” Anna admits on the video as she arches her back against the sign for Mexia High. “I was flat-chested,” she says. “But now I have curves. See? Ooh la la!”

In the 1990s, Mexia had only one famous industry, and it was Anna Nicole Smith.

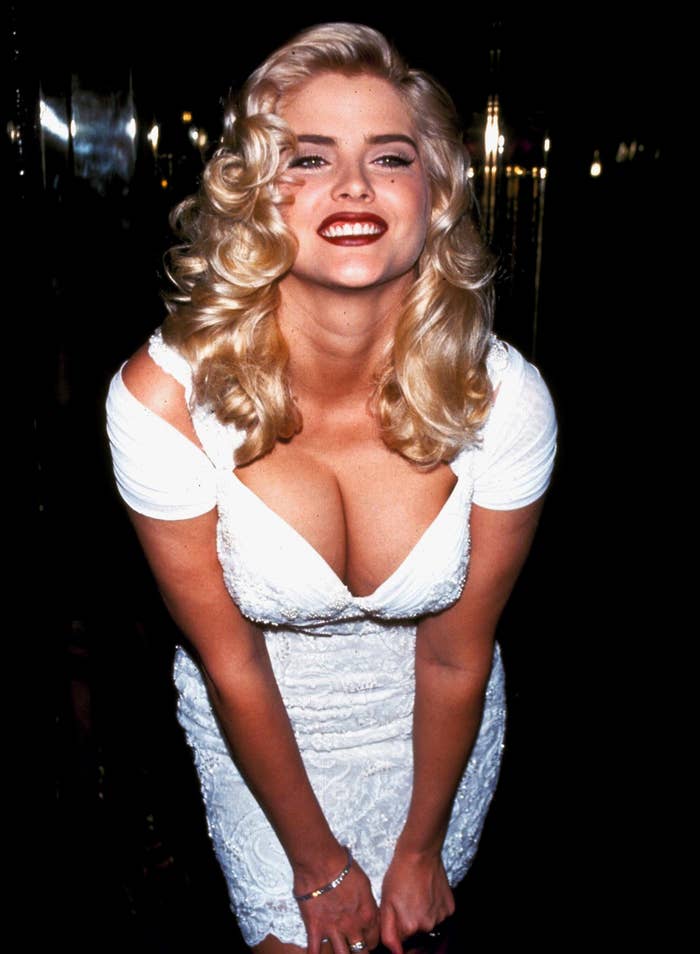

Anna Nicole Smith flaunts her brand-new curves on the dusty streets of Mexia, her famous double-D breasts straining against the floral and denim of her down-home drag. In the 1990s, Mexia had only one famous industry, and it was Anna Nicole Smith. She was, the professionals who worked with her said, brilliantly and naturally gifted at the art of seducing through a lens.

“She is one of the most awesome people in front of the camera I’ve ever seen,” one photographer said at the time. “She gets into a sexual trance.”

She was, Skip Hollandsworth wrote in a 1993 Texas Monthly article, “a magnificent Amazonian creature,” capable of “giving the camera the kind of deep, smoldering look that suggests she can handle any kind of trouble that comes her way.”

The question people spent less time wondering about, during her initial rise to fame, was just how much trouble had come her way in her short life, and whether she was as capable of handling it as she seemed. But maybe the real question was not what happened to Anna Nicole Smith, but what happened to Vickie Lynn Hogan.

“People always ask me about my childhood,” Anna told the camera in one episode of her 2002 E! reality TV series, The Anna Nicole Show. “Well, I didn’t have a childhood, so I’m livin’ my childhood now.”

“Lord, if you could have known how poor that girl was,” her aunt, Kay Beall, told Hollandsworth. “I used to slip her some of my food-stamp money just so she could buy herself some candy.” According to Hollandsworth, Vickie Lynn lived in a house so cold that she had to wear flannel pajamas under her clothes to stay warm in the winter, and stole toilet paper from a nearby restaurant because her family couldn’t afford any.

Vickie Lynn began living with her aunt Kay when she was 15, not long before she was expelled from Mexia High for fighting. “You want to hear my child life?” Anna once told an interviewer who pressed her to talk about her years as Vickie Lynn. “You want to hear all the things [my mother] did to me? All the things she let my [stepfather] do to me, or let my brother do to me or my sister? All the beatings and the whippings and rape? That’s my mother.”

Coltish, glancing-eyed, and nearly 6 feet tall in bare feet, Vickie Lynn looks, in photos from her Mexia years, like she might just as easily have gone in the direction of a high-fashion model. But the high-fashion look didn’t count for much in Mexia, or even in Dallas or Houston, and Vickie Lynn needed a body that would help her survive the world she lived in, and maybe even escape it.

By 17, Vickie Lynn was a married woman. By 18, she was a single mother. After alleging that her husband, Billy Wayne Smith, had abused her, she took their 3-month-old son, Daniel, and left Mexia for good.

Something happens when you make the two-hour trip from Mexia to Houston. Dry Texas farmland gives way to the pink skies and sudden downpours of the Gulf. Though inescapably connected with a commodity drawn up from deep in the ground, Houston belongs to the ocean. It’s a port city, and like all port cities, it is a place of transformation: a place where the skyline can change seemingly overnight, where fortunes can be won and lost in an instant, and where the people who kept you down all your life can’t keep you down anymore, because you can become whatever you say you are — or at least whatever the city will pay you to be.

In Houston, Vickie Lynn got the kinds of jobs she could get, at Walmart and Red Lobster, and struggled to pay the bills. But she had ideas. Vickie Lynn — who was now living under her married name, Smith — was a Texan, and Texans understand the nature of boomtowns. Houston, which had once been the oil capital of America, was in the grips of a crippling oil-industry recession by the time Vickie Lynn came to town in 1986. But Houston had another world-famous commodity: the breast.

The silicone breast implant was invented in 1961 by two Baylor University surgeons, and by the 1980s it was almost as synonymous with Texas-sized dreams and desires as the lasso was. Houston was the implant capital of America, and, by the early ’90s, the implant-related lawsuit capital of the world, as women sued manufacturers for — and often won — blowout settlements that ranged into the tens of millions, alleging that their implants had caused them to suffer everything from lupus to scleroderma to chronic fatigue.

For every woman desperate to get her breast implants removed, there were still others saving their money to buy

a pair.

Yet for every woman desperate to get her breast implants removed, there were still others saving their money to buy a pair. One of these women was Vickie Lynn, who had recently taken her first job dancing, at the Executive Suite, a strip club near Houston Intercontinental Airport. She was scarred with stretch marks, flat-chested, and taller and sturdier than the waifish dancers Houston businessmen seemed to favor — both too big and too small for the business of seduction.

Yet there was something about the girl who was now performing as “Nikki” and “Robin.” She struck people as genuine — a little rough around the edges, but open. Real. “She definitely stood out among the girls,” Terry Allen, who managed the Executive Suite, said of Vickie Lynn, who was just 19 when she auditioned at his club for her first job. “She didn’t have the hard look.”

After years of surviving on minimum wage, Vickie Lynn was finally making enough money — $50 to $200 a night — to start putting some aside for her future. So she did: She began saving up for a pair of breast implants. At Rick’s, the legendary Houston strip club that some claimed had singlehandedly popularized the silicone implant, a dancer could earn as much as $600 a day — an unimaginable amount of money compared with the $60 a week Vickie Lynn had been making at Walmart. All she needed to get in the door was the right body, and so she saved up for one, often popping a Valium or a Xanax on the nights when she wanted to disappear from herself before stepping out onstage.

It took multiple surgeries to create Anna Nicole Smith. Each of her implants contained 700 milliliters of fluid, and one of them would rupture within a few years, requiring reconstructive surgery. It was after this metamorphosis that Anna turned to prescription painkillers, to manage the lasting discomfort that both the surgery and the weight of the implants themselves caused her.

But she finally had her body. That was the way she always described it: as if, prior to that moment, she had no body at all, and she had not even really existed.

“I can just relate to her,” Anna said of Marilyn Monroe. “Especially after I got my body — then I really could relate to her.” She seemed to be following in Marilyn’s footsteps less by recreating her famous body than by realizing that a body could be created: that your physical self could be both the tool that rescued you from the world you knew and the shield that protected you from it.

It was in Houston where Anna Nicole Smith bought her new body, and it was in Houston where she met J. Howard Marshall, the tycoon who would soon offer her both his money and his name. She was dancing at Rick’s, and she met him not because she had successfully completed her transformation from Vickie Lynn to Anna Nicole, but because she still didn’t quite belong.

“I was aware of Anna Nicole Smith,” Robert Watters, the president of Rick’s, said of Anna’s time there, after her wedding to J. Howard Marshall made their meeting place even more of a Houston landmark. “But she only really stood out,” Watters said, “because I had to comment on her weight to the management, make sure she worked on daytime rather than nighttime. We have standards.”

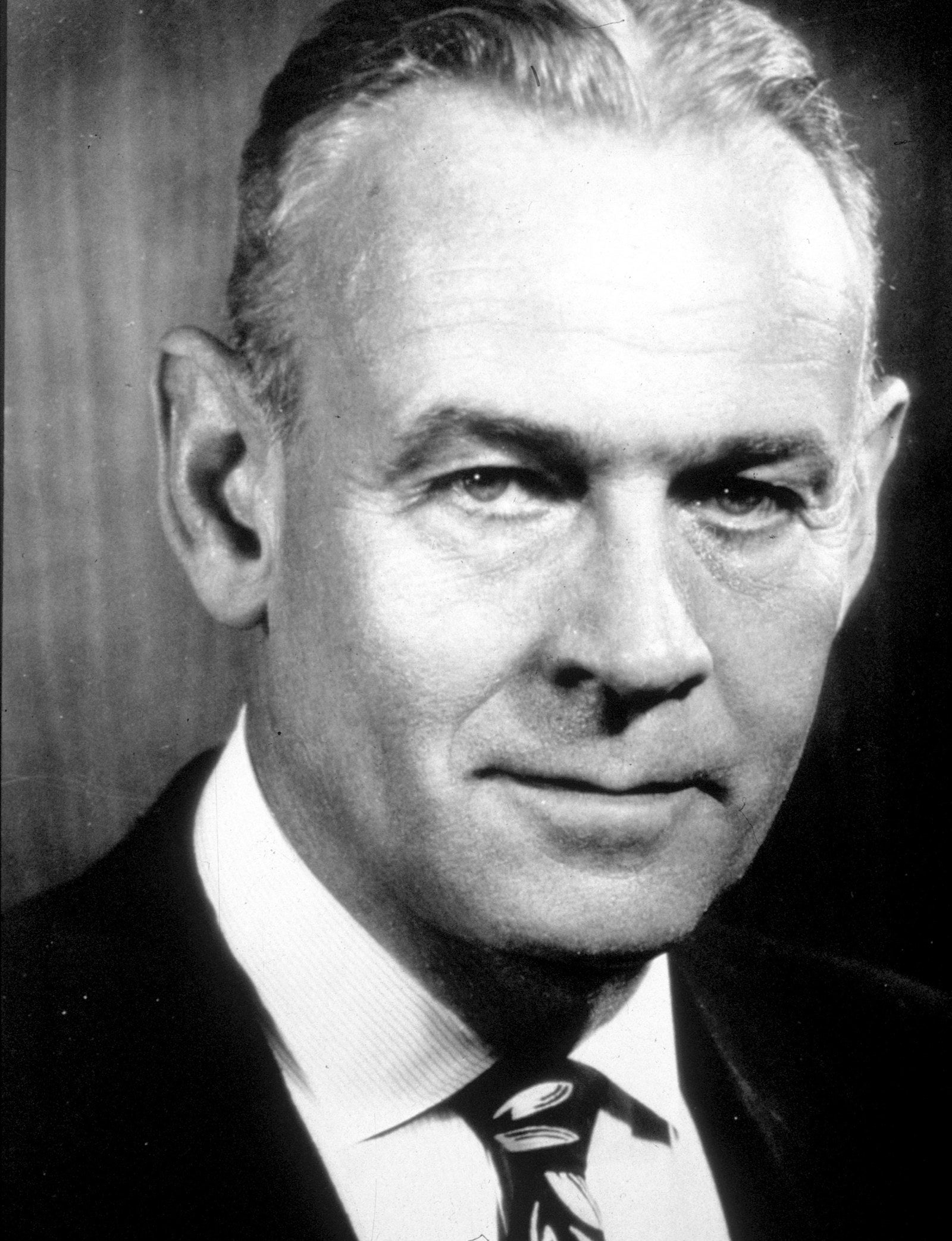

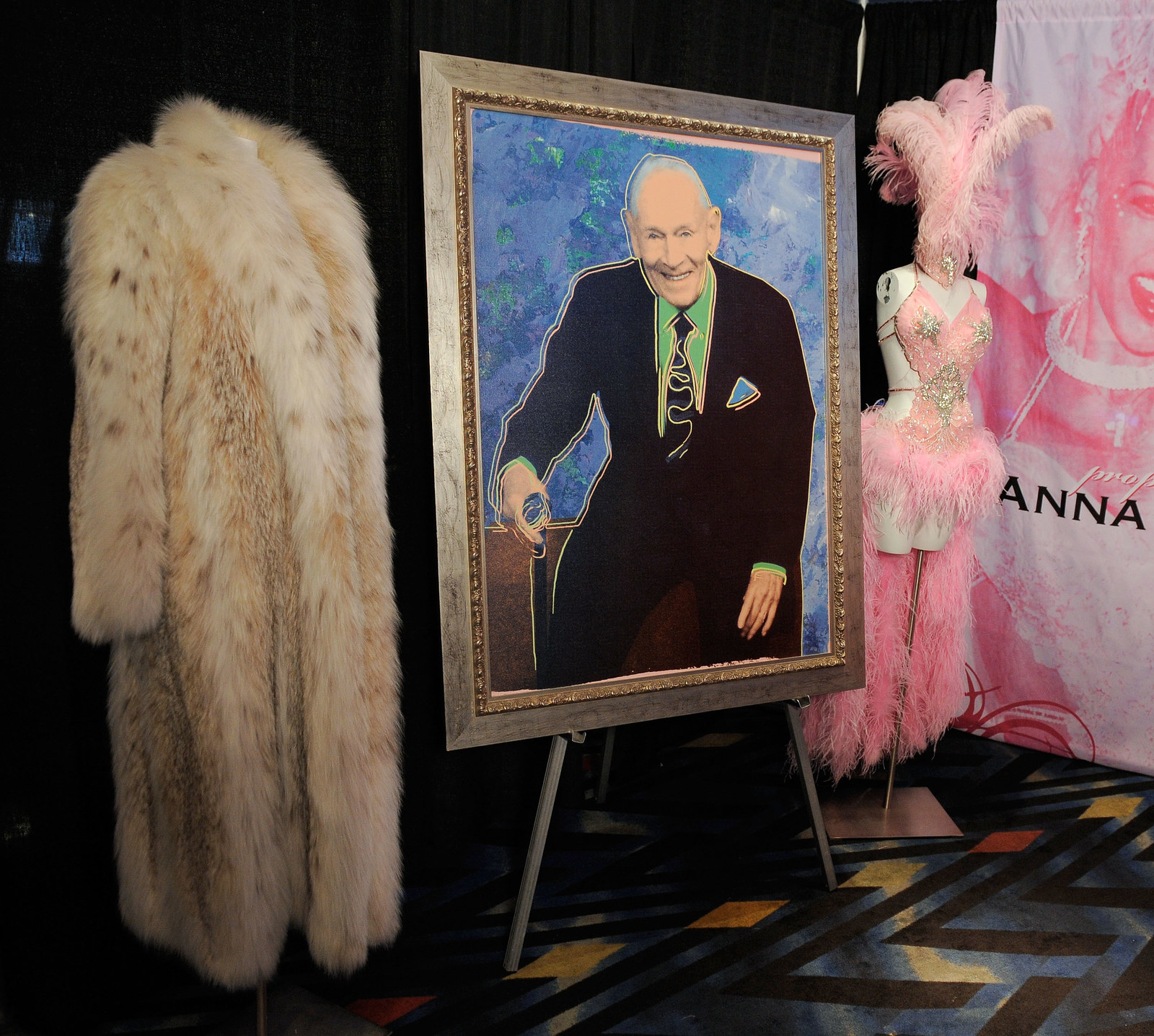

J. Howard Marshall, who was too frail to leave the house at night, came into Rick’s one afternoon in 1988, and Anna found her gusher.

“I was on stage,” Anna Nicole Smith wrote in the bride’s book at her wedding, describing their first meeting at Rick’s in 1988. “He was in the audience, and he was lonely and I started talking to him and we just started being friends.”

Calling J. Howard Marshall “older” than Anna Nicole Smith would be as misleading as simply calling him “rich.” Born in 1905 to a Quaker family, he attended Yale School of Law, got rich on the East Texas oil boom of the 1930s, and got filthy rich after brokering a particularly savvy deal with Koch Industries in the 1960s. He was not just a successful businessman, but a Houston legend: a man who commanded both a fortune conservatively estimated at $1 billion, and the kind of business acumen generations of younger men coveted.

He also had a soft spot for strippers. In 1982, after his second wife — a woman he had adored and nicknamed “Tiger” — was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, Marshall found solace with Jewell DiAnne Walker, a 42-year-old Houston stripper known to both her intimates and her enemies as “Lady.” Marshall, who was 77 at the time, was, as he later said, “blinded by love. I did more or less what she asked me to do,” he claimed, “and I don’t make any bones about it. I was a damn fool. But men in love do stupid things, and I was sure guilty.”

Later, many who chronicled the relationship between J. Howard Marshall and Lady Walker — much like those who would chronicle the relationship between J. Howard Marshall and Anna Nicole Smith — would assume that Lady meticulously extracted Marshall’s wealth, relying on her unique powers of seduction to get him to buy her a new Rolls-Royce because it matched her outfit, or to tip her fingers with 14-karat gold false nails. In 1984 alone, Marshall spent $1.2 million on Lady — but her demand for luxury seems to have been matched only by her suitor’s eagerness to provide it. He had found himself, at the end of his life, with more power and money than he knew how to use, and so he set about using them to attain the one thing he didn’t have.

“To love and be loved — to a man who has dedicated his life to his work, this is truly life’s greatest experience,” Marshall wrote in one of his many letters to Lady Walker. In another: “I belong to you.”

Marshall was devastated when Lady died suddenly while undergoing a facelift in 1991. His devastation turned to jealous rage when he saw that Lady’s will named another man as the love of her life. He had maintained that he accepted her sexual relationships with other men, but he seemed to believe that her affections, at least, were his and his alone — that his vast riches allowed him, as Mimi Swartz wrote in Texas Monthly, “to have a controlling interest in another human being.” After Lady’s death, Marshall sued to regain ownership of all the gifts he had lavished on her while she was alive. At the same time, he began turning his attention to a new woman: Anna Nicole Smith.

The Guess campaign also marked the moment when her new identity snapped into place, as it was Guess president Paul Marciano who rechristened her Anna Nicole.

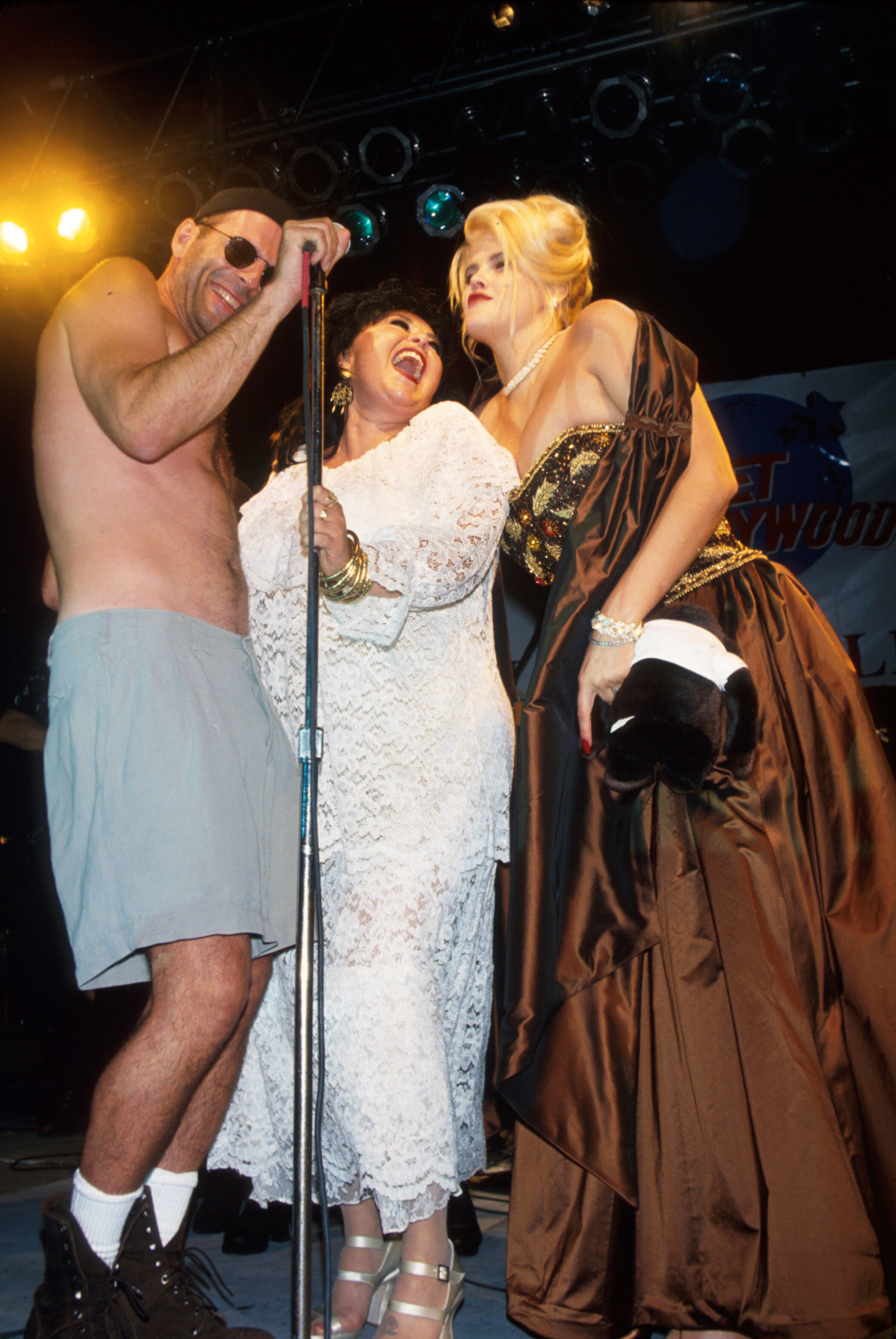

By 1991, Anna had been seeing Marshall for three years, but only as much as his dedication to Lady Walker allowed. At the same moment that Marshall set his sights on Anna, however, the world set its sights on her. In 1991, Anna was also going out with a bodybuilder named Clay Spires, and, at his suggestion, she took her body to an open call for Playboy models. At first, she was scared to take her clothes off, but within a few months she was posing in the centerfold. In 1993, she was named Playmate of the Year, and would soon become famous beyond even Hugh Hefner’s world. She won roles in The Hudsucker Proxy and The Naked Gun 33⅓. She replaced Claudia Schiffer as the Guess Jeans girl, her ad campaign for the company blending smoky-eyed glamour with a smile as warm as Texas sunshine.

The body that had been too much for the men of Houston was, in the pages of a magazine, suddenly just right. The Guess campaign also marked the moment when her new identity snapped into place, as it was Paul Marciano, Guess president, who rechristened her Anna Nicole. By emulating Marilyn Monroe, who herself seemed to embody her period’s idealized essence of feminine sexuality, Anna Nicole Smith had become, in the words of psychologist James Hollis, “an imitation of an imitation,” unburdened by any troubling specificity.

She found her way into the pages of Playboy on her own, and landed the Guess Jeans campaign based on her visibility there. But Anna also knew that anyone who found out about her wealthy benefactor would refuse to give her any credit for reaching the spotlight on her own. It was a sense of legitimacy that she seemed to want badly, and she was keenly aware of how arbitrarily it could be snatched away from her.

By 1993, Anna Nicole Smith was famous enough to reach American living rooms not just through mail-ordered videotapes, but via primetime — though some remained reluctant to welcome her there.

“I don’t dress up much,” Anna confessed during an appearance on Live With Regis and Kathie Lee.

“And when you do, you don’t wear much,” Kathie Lee added.

“Texas-sized model Anna Nicole Smith has proven that big can be beautiful,” Entertainment Tonight anchor Mary Hart said with a barely suppressed eye roll, in a segment that also noted its subject’s weight. “We caught up with Anna where she’s most natural: down home on her ranch, chasin’ critters.”

In her Playboy video, she called it “my ranch I’ve wanted all my life,” and the tape also showed her playing there with her son, Daniel Wayne Smith, who was now a towheaded little boy of 7. “Daniel is truly the love of my life,” she said in the video. “I am so thrilled to be able to give him the things I never had. We just love playin’ on the farm with all of our animals. He’ll always be my number-one cowboy.”

“It was worth it,” she told Entertainment Tonight, of her decision to pose for Playboy. “I mean, I’m here.”

She also had not just one dream home, but as many as she wanted — though she was never clear on how she was able to afford them, or why her rise to fame had been so lucrative. She moved into a new house in Houston, but city life was still an adjustment (“When she could not sleep,” Dan P. Lee wrote in New York magazine, “she’d have her favorite sheep brought there from the ranch to cuddle with”). And when Anna went to Los Angeles to meet with all the photographers and directors who suddenly wanted to work with her, she rented a house that Marilyn Monroe had once lived in.

“I finally feel like I’m becoming somebody,” she told People magazine in April 1993. “I really think like I can do something.”

As Anna’s career took off, Marshall might have felt he needed to up the ante to keep her affections. So he took her to Harry Winston, where, a salesperson later told Mimi Swartz, as if of a child in a candy store, “She was allowed to pick out what she liked.” The girl who had grown up stealing toilet paper from restaurant bathrooms selected three diamond rings, two diamond necklaces, two pairs of diamond earrings, and one diamond bracelet, for a grand total of $2 million.

Later, when called on to describe her relationship with Marshall, Anna would say, “He took me out of a terrible place, took care of me. He was my savior. It wasn't a sexual ‘baby, oh baby, I love your body’ type love — it was a deep thank-you for taking me out of this hole.”

What had helped her escape from that hole, it seemed, was a performed sexuality that she had honed to unmistakable clarity: a voice that reached up into the open air and beckoned someone to reach down and take her out of the life she was living. J. Howard Marshall heard her, and he lifted her up. Now it seemed the whole world could hear her too.

When interviewed by Mimi Swartz, the owner of the wedding chapel where Anna and J. Howard Marshall married in June 1994 recalled Anna insisting, “I’m not marrying him for his money. He’s been begging me to marry him for over four years. But I wanted to get my own career started first. Have my own money.” Later, when Marshall v. Marshall was tried, for the first time, in Texas probate court in 2001, Anna recalled that she had initially refused Marshall’s proposals of marriage “so nobody could call me a gold digger, but I guess that backfired, didn't it?”

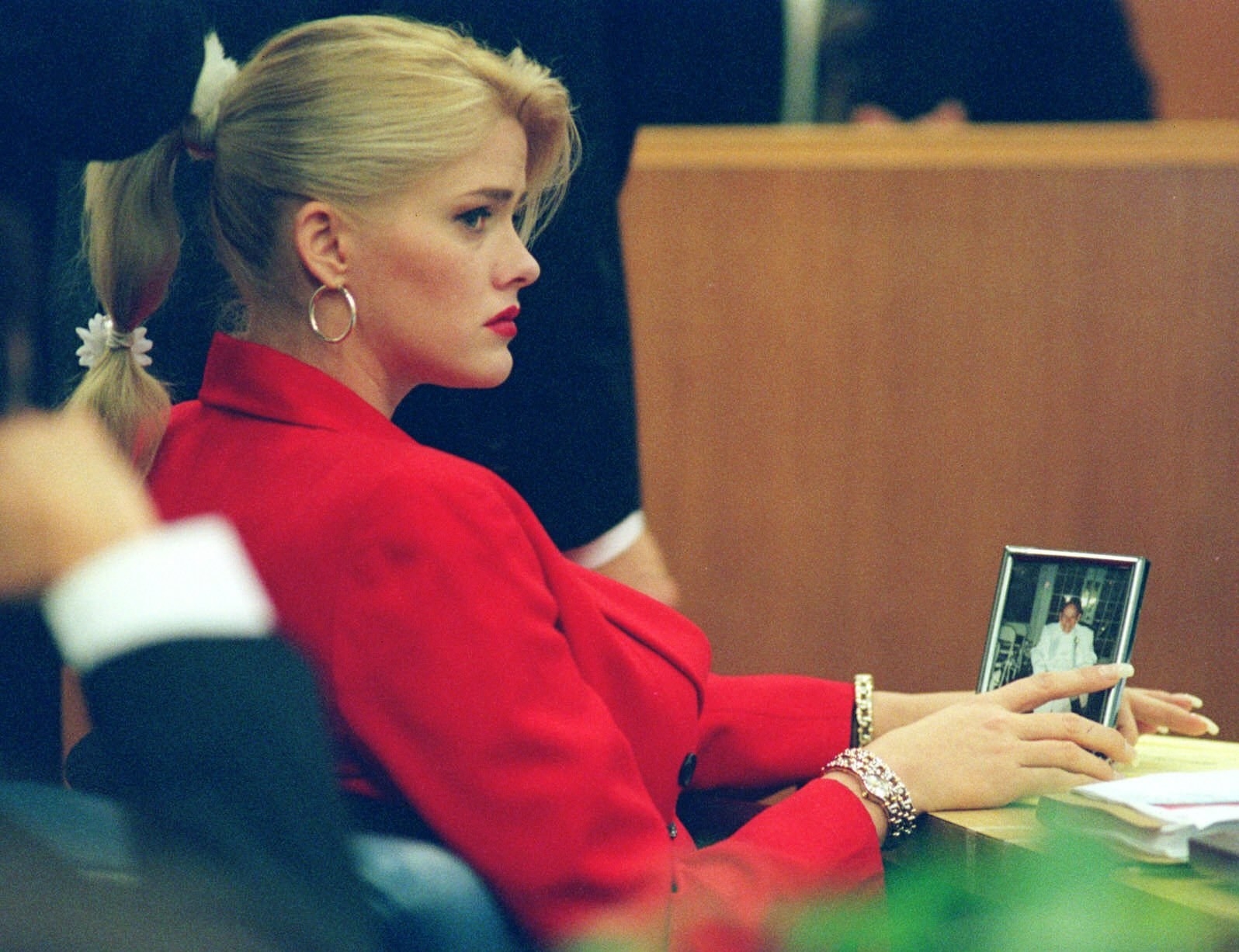

The most widely televised moments in the Texas leg on Marshall v. Marshall — a traveling show that would eventually make it all the way to the Supreme Court — came when Anna Nicole Smith took the stand, beginning on the day after Super Bowl Sunday. Most of the time, Anna found herself facing off against Rusty Hardin, a former prosecutor whose unbroken winning streak with felony jury trials made him a living legend in Houston’s legal community. He represented J. Howard Marshall’s son Pierce, and his most prominent duty was his cross-examination of Anna Nicole Smith. She called him Rusty, and he called her Miss Marshall — a name that suggested she still existed under her husband’s name but couldn’t even claim the kind of legitimacy that would grant her an inheritance: a Miss. J. Howard Marshall had owned her outright, but she could not say the same of him.

Hardin approached Anna with the scorched-earth strategy he had once loosed on accused rapists and murderers. He had always been particularly adept at convincing jurors that anything but a guilty verdict would render them guilty of aiding and abetting the erosion of human decency, and he recognized that it was beside the point to attempt to make Anna Nicole Smith look unsympathetic. She would do it all on her own.

“Miss Marshall, have you been taking new acting lessons?” Hardin asks after she proclaimed her love for her late husband.

“Screw you, Rusty,” Anna says tearfully. Backed into a corner, painted as both a manipulative liar and a dumb country girl, and challenged by a powerful man, she resorts to aggression. Nothing could make her look worse, or make Rusty Hardin’s job easier.

“Are you contending,” Hardin says, during one particularly successful moment in his cross-examination, “that in December of 1994, this man … was being kept from giving you money by his son?”

In the video of this portion of the trial — video that would eventually, inevitably, like so much of Anna Nicole Smith’s life, make it onto TV — Anna seems heavily sedated, but she is also intensely focused on keeping up with the proceedings. For once, she isn't withdrawn or defensive. She leans forward, listening carefully, trying to get it right.

"It's very expensive to be me," Anna Nicole Smith says at another point during her time on the stand. "It's terrible," she tells the jury, "the things I have to do to be me."

“Well,” she responds haltingly, “he told me that, um, Pierce would only give me $100,000 for my Christmas. I know that. And he asked me what I wanted, and that’s when I said half cash and half—”

“Miss Marshall,” Hardin interrupts, “what kind of world is it when people start talking about ‘only $100,000 for Christmas?’”

Anna’s counsel objects, but she doesn't seem to hear them. She knows the answer to this question. Finally, she's been asked a question she knows the answer to.

“My husband spent hundreds of thousands of dollars on me,” she explains, as if this had perhaps simply never occurred to Rusty Hardin. “A hundred thousand dollars is not a lot of money to me.”

“So — pardon me?” Hardin says, and this is the moment when he realizes he has what he needs. He’s set the trap and she’s walked straight into it, without so much as a backward glance. “A hundred thousand dollars is not a lot of money to you?” he repeats.

“No, sir,” Anna says. “My husband threw money at me. You don’t understand. I mean, he — it — my—”

She tries to find words that describe the sheer magnitude of the experience. She can't. Of course she can't. No one has ever really been able to; if they could, then maybe people wouldn’t be quite so ready to hate her.

For neither the first nor the last time during the case, Anna Nicole Smith is at a loss for words, but this time she doesn’t seem angry or ashamed. Instead, she smiles, perhaps at the memory of the time when a powerful man’s desire to take care of her was the driving force in his life, and he was powerful enough to make the whole world want to take care of her, too.

“It's very expensive to be me,” Anna Nicole Smith says at another point during her time on the stand. “It's terrible,” she tells the jury, “the things I have to do to be me.”

The jurors ruled in Pierce Marshall’s favor, but the case dragged on, and Anna's role in the ongoing saga cemented her status as a national punchline. It was a part she had already been playing for years. The only difference now was that there seemed no hope she could ever escape it.

But Anna Nicole Smith’s descent from stardom — and the sense of safety it afforded, illusory as it was — had already begun to gather speed years before, in August 1995, when J. Howard Marshall died of stomach cancer. By then, Anna had already been outed in the press as woman who had married a man for his money, and bought the body that made her famous. After she began fighting her husband’s heirs for the lifelong financial security she said he had promised her, her stock declined even more dramatically. As she grasped for the money that was slipping away from her, and struggled to maintain the beauty that had been her only other source of safety, the media outlets that had celebrated her seemingly serendipitous rise to fame now took just as much delight in dismantling it.

In 1995, Anna starred in To the Limit, an ultra-low-budget thriller whose director, Ray Martino, introduces her character as she gazes into the mirror, admiring her curves to the strains of “Ave Maria.” Anna moved in with him soon after J. Howard Marshall’s death, gained weight, deepened her dependence on prescription drugs, cut ties with her family, sucked on pacifiers, and declared bankruptcy.

Dan P. Lee reported in New York magazine that, one day in 1995, as Martino was leaving to take Daniel to school, Anna told him, “I don’t wanna be alive no more.” He comforted her, left her alone, and returned to find she had overdosed. She survived, but ongoing physical pain, as well as feelings of anxiety and persecution, threatened to overwhelm her.

“She didn’t look like the glamour girl she tries to be,” a voiceover says in an Extra segment on Anna’s appearance at the 1996 Academy Awards. “Her shoulder-length hair seemed to go everywhere, and her lipstick looked slopped on.” Yet the show left its most damning accusation to its subject.

“I’m not fat!” Anna says to the cameras, slurring her words as she tries to cinch the waist of her dress beneath her famous breasts. And she wasn’t. But she had betrayed the public by failing to maintain the fantasy body she had become famous for. She had returned to the camera’s gaze after a rehab stay at the Betty Ford Center, healthier than she had been before, but different. Anna Nicole Smith was still beautiful, still desirable, and she still had the body she had worked so hard to build. But the cracks were showing. A fantasy body was not supposed to feel pain or undergo addiction, not supposed to age, to change, to betray the most intimate facts of its owner’s existence — but Anna’s did. It was perhaps not the actual changes her body underwent but the fact that her body could change at all that turned the public against her. She was a fantasy. The rules were simple. How dare she break them?

“It’s hard to believe what can happen,” Anna had told Skip Hollandsworth in 1993, “just because people want to get a look at you.” Now the public was scrambling to look at Anna Nicole Smith not in wonder, but in disgust.

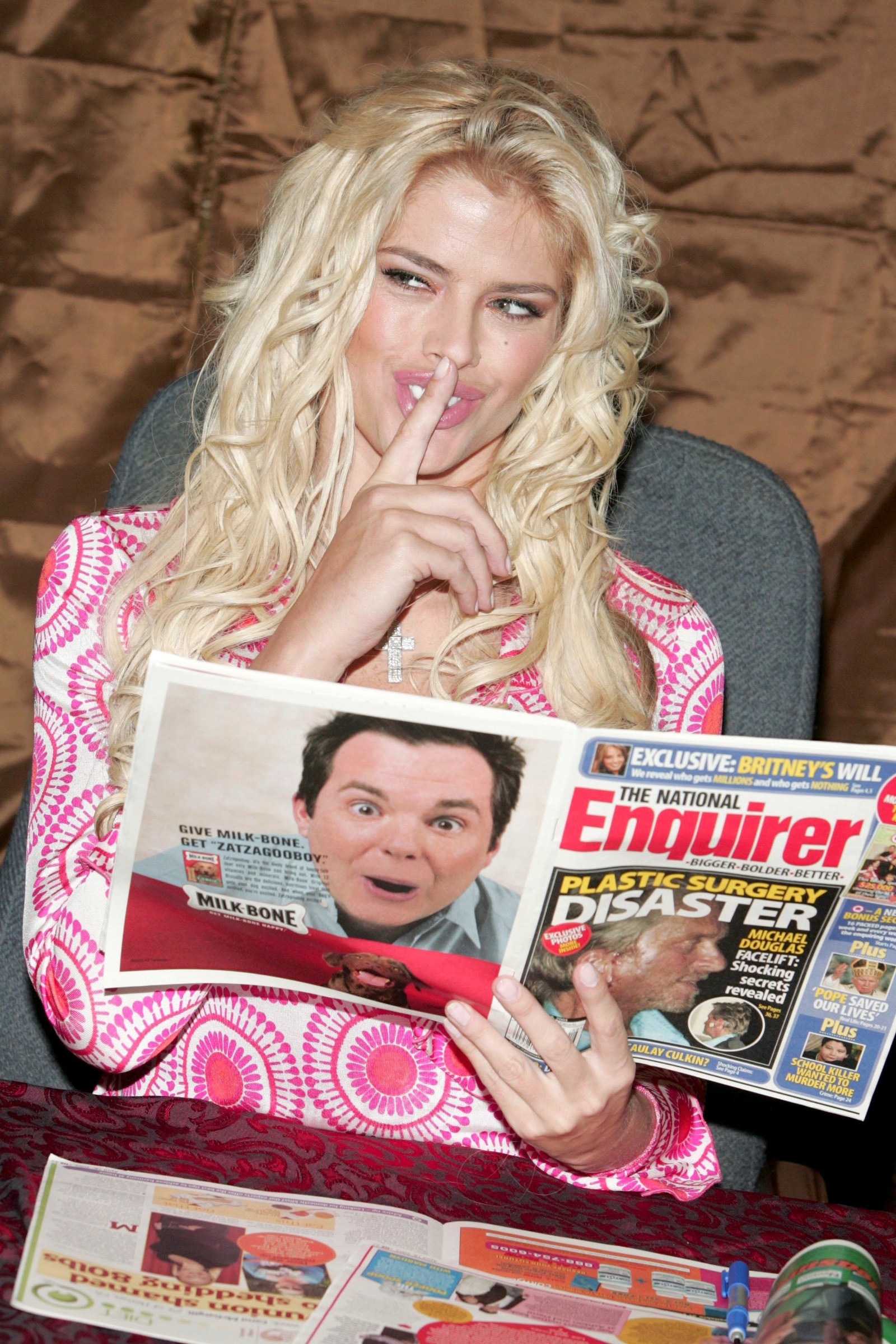

In 2002, with offers for mainstream movie roles now well in the past, she agreed to star in E!’s The Anna Nicole Show. “It all disappeared as fast as it came,” the theme song went, as a cartoon Anna danced on a stripper pole, watched her stacks of money vanish, and brushed herself off, vibrant and unstoppable as ever.

“Only four days old,” Carina Chocano wrote in Salon, “The Anna Nicole Show has already been compared to a train wreck (the Hollywood Reporter, the Tampa Tribune, the Christian Science Monitor and the Hartford Courant), a car wreck (the New York Times and the San Francisco Chronicle) and a cruel, exploitative joke. … If a flamboyant sense of the vulgar is all that Anna Nicole has left (she has yet to collect on her late husband’s massive fortune), then, to her credit, she is milking it for all it’s worth.”

Some reviews were even more blunt: “There's really no nice way to put this,” Tim Goodman wrote in SFGate. “She comes off as dumb as a post.” Yet, for as long as Anna remained in the spotlight, it was possible to see her as someone who was savvy enough to profit off of the public’s enduring fascination with her, and to maintain some tawdry brand of power over the American people — rather than a human commodity who TV networks and advertisers could profitably push into demeaning and damaging work, so long as she was desperate enough to take it.

The reality the show depicted was a little more complicated. Anna Nicole Smith was falling apart, but it wasn’t her body that had changed so much as her ability to control its power. By the time the series premiered, the act of simply inhabiting it seemed to exhaust her. Regardless of whatever prescription drugs she had or had not become dependent on by that time, she was often, for whatever reason, not entirely there: vacant or nonresponsive or simply half-asleep. She could no longer do the things she had to do to be her.

Anna’s ongoing troubles were painfully visible on her reality show. In one episode, she goes to the dentist to have her teeth capped with 20 crowns, since the stress of Marshall v. Marshall has caused her to begin grinding her teeth, leading to lasting nerve damage.

“I only started going to the dentist in my twenties,” she tells the reality show’s cameras. “I hate the dentist because they hurt me … I told ‘em they had to knock me out good.”

The episode shows Anna’s lawyer and dedicated protector, Howard K. Stern, who Anna shared a close but apparently nonsexual relationship with during the last several years of her life, leading an already heavily sedated Anna to the dentist’s office, and reassuring her that they will knock her out good as soon as they get her in the chair. Much of the series shows Howard maneuvering Anna through various hallways, comforting and cajoling her, trying to make the world seem a little less harsh, and often failing.

Of all the elements that killed The Anna Nicole Show’s ratings, perhaps the most damning was its contradiction of that most beloved of American dreams: the rags-to-riches story. It’s a phrase that doesn’t exactly lie, except by omission, suggesting that poverty is only ever an external condition — a question solely of how much money you have in the bank, and could never be, as it so frequently is, a legacy of poor health, disability, abuse, and helplessness both literal and learned. In the American dream, poverty is easily banished and rarely returns — and never shows up to stand outside your house, staring in at you, as Anna Nicole Smith’s cousin Shelly did in one episode.

Of all the elements that killed The Anna Nicole Smith Show's ratings, perhaps the most damning was its contradiction of that most beloved of American dreams: the rags-to-riches story.

“Don't let 'em do this to me,” Anna says, half-asleep, when Howard informs her that her cousin has shown up at her door, along with a film crew. “I don’t trust nobody,” says Anna, who by this point refuses to see any member of her Texas family. “I’ve already had them fuck me over.”

Shelly’s camera crew ends up in a standoff with Anna’s camera crew. Shelly’s crew relents, and Anna’s crew films her eating doughnut holes and milk, slowly rising out of her stupor, and listening, with growing curiosity, to Howard’s description of Shelly.

“She didn’t have no teeth?” Anna asks, shocked. But a moment later, she can think of at least one explanation. “She didn’t take care of herself,” she concludes. “She must not have a boyfriend, then.”

“How old is she?” Howard asks. “I couldn’t even tell how old she was. I couldn’t tell if she was, like, 25 or if she was, like, 50. Seriously.”

“She looks that bad?”

“No, it’s just — it just was the teeth.”

“She’s young,” Anna says. “I fixed her teeth before. They were all black … and I fixed them to where they were all white and pretty. I guess she fucked them up again.”

Finally, Anna agrees to go to dinner with Shelly if they can be filmed exclusively by Anna’s crew, and Shelly agrees. Even in the grainy and awkwardly edited format of early reality TV, the dynamics of the relationship in that moment are clear, and painful to behold. Shelly is working hard to draw Anna out, to make her reminisce with her, to reconnect. Anna is reluctant, holding herself back, not seeming fully present in the conversation — maybe because she’s worried Shelly will ask her for money (she will), and maybe because remembering the part of her life that Shelly is connected to is just too painful. Because she does not want to be the person who knows this life.

“You still got your beautiful hair,” Anna says to Shelly, and Shelly asks Anna for a picture where she is smiling, so Shelly can ask the dentist to make her teeth just like Anna’s. Shelly doesn’t eat, just drinks, and when customers at the bar send a drink over to Anna (“They want you to do a shot,” Howard says wearily), Shelly drinks it for her.

“I swiped a doctor,” Shelly says, near the end of the night. “I did! When I was deliverin’ Harley. You know how they do the finger thing and see how far along you are and all this ’n’ that? And I was like, ‘If you don’t get your fingers out of me’ — I know they’re not supposed to leave ’em in there, okay? ... And I said, ‘Man, if you don’t get it out, I’m gonna hit you.’ That nurse looked at me and she said, ‘We will have no violence in this room.’ I grabbed her … I said, ‘I’ll tell you about violence.’ ... [The doctor] wouldn’t listen, so I reached up with my left hand, and I said, pow. I hit him right in the jaw! I smacked him right in the jaw. The nurse goes, ‘He’s gonna sue you for that!’ I said, ‘Bitch, fuck you. What’s he gonna get, a food stamp?’”

And Anna finally laughs, and Shelly joins her, because this is the punchline, or at least as close as they will come to having one, as opposed to being everyone else’s.

In Anna Nicole Smith’s 1993 Video Centerfold, Anna assures the viewers that, since her appearance in Playboy, “Things just keep gettin’ better and better.” She had the ranch she had always dreamed of. She had reunited with her father, who she had never known but tracked down once her newfound wealth gave her the resources to do it. (“Here she is and here I am,” he said as Anna gazed at him adoringly, “and I think she’s really done great for herself. She’s beautiful, and I love her.”) And she was able to give her son everything she had never had, and made sure he never had to experience the kind of trauma she had worked so hard to escape. This was what fame, money, and success could do for any American who grabbed the brass ring: All the pain you’d experienced faded into the vaguest of memories. History didn’t have to repeat itself — not if you could buy your way out.

But in Anna Nicole Smith’s life, history would repeat itself over and over again. Her relationship with Daniel — her “number-one cowboy” — grew troubled, particularly after The Anna Nicole Show began airing. “Your mom is so fucked up,” one classmate told him, after his mother’s difficulty making her way through daily life, branded as entertainment, made its way into millions of living rooms. Daniel started hiding his mother’s prescription drugs from her, and — perhaps an even greater betrayal — drinking and disappearing all night without telling her where he was going. Anna kicked him out, and continued trying to get pregnant with a second child, having at least one miscarriage in the process. She was desperate to have another baby, she wrote in 2000, “before Daniel leaves me.”

Daniel left her on September 10, 2006, just hours after she gave birth to his baby sister, Dannielynn. The day before, he had arrived in the Bahamas, where Anna had given birth, to reconnect with his mother and meet his new sibling. (Anna had conceived Dannielynn with photographer Larry Birkhead, but she named Howard K. Stern, who was with her in the hospital that day, as the father.) Mother and son shared a loving reunion, and Daniel rocked Dannielynn in his arms. The family fell asleep in Anna’s hospital room, and the next morning, Daniel was dead.

As far as anyone knew, he hadn’t made any sound or sign of struggle during the night. Anna had simply woken up, and found that he wasn’t breathing. He was 20 years old, and his cause of death was ruled to be combined drug toxicity. It was the same cause of death that would be listed when his mother died, just five months later.

When Anna Nicole Smith died on Feb. 8, 2007, at the age of 39, she was suffering from both a painful infection and 105-degree fever, both caused by abscesses she had developed after injecting herself with vitamins and growth hormones, which she had hoped would help her lose weight. She was taking Klonopin, Ativan, and Valium, and sucked liquid sleeping medication from a baby’s bottle. She was so grief-stricken after Daniel’s death that she found herself unable to care for Dannielynn. For years now, she had been unable to do the things necessary to be “Anna Nicole.” Now, simply being had become impossible.

The media greeted Anna Nicole Smith’s death with everything but surprise. Tabloids published photographs both of her last moments with Daniel’s body, and, a few months later, of her own dead body, the National Enquirer promising readers a “Chilling FINAL IMAGE of Anna Nicole Smith.” Yet even this kind of exposure paled in comparison to the wrenching view of her life that Anna had willingly granted the public while she was still alive.

The media’s reaction to Anna Nicole Smith’s death also betrayed the unspoken belief that there was really only one way for the story to end. After all, it had happened so many times before. The woman rose up, made powerful by beauty, and then found herself falling, her beauty fading, her power eroding, her ugliness as she tried to cope with this loss providing spectators with the reassuring feeling that such power is never really worth having, if losing it looks like this. And the only person more deserving of this humiliation than the cluelessly beautiful woman is the beautiful woman who, even more unforgivably, knows she is beautiful: the woman who knows she is worth something to the world, and leverages her value to escape a life she can no longer stand. The woman who looks back at a world that always wants something from her, and asks, How bad do you want it? How much are you willing to pay?

“What set the 1990s apart from any previous yellow-tinged epoch,” David Kamp wrote in Vanity Fair in 1999, “are two factors: advanced technology and increased vulgarity. It’s the dance between these factors, the downloadable and the down-and-dirty, that had led to the Tabloid Decade’s particularly explicit brand of tabloidism. That has enabled us to learn not only that the president was a philanderer but also that he inserted a cigar into the vagina of a young lady named Monica S. Lewinsky; not only to discover that Prince Charles had an affair with Camilla Parker Bowles but also to hear recording of him stating his wish to be her tampon.”

What seems to have alarmed many Americans about the rampant spread of ’90s “tabloidism” — which could call on Anna Nicole Smith as one of its many poster girls — was its ruthlessly disinterested exposure of male weakness. Again and again, the most lucrative tabloid dramas of the decade hinged on a powerful man who should have known better, who must have known better, risking it all for sexual indiscretion with a woman, and often a young and powerless one at that. Confronted with stories like this, it was hard not to blame the women for the embarrassing and sometimes abusive things these powerful men did to them: Surely a Houston oil tycoon or a famous preacher or the president of the United States couldn’t be like that really. Surely this woman had made him do that, somehow. Surely it was her fault, and not his.

Anna Nicole Smith first became famous as a woman blessed with more beauty and money — more sheer power — than most people could dream of. Even when her fame was tainted by the revelation of all that she had done to secure such riches, it was perhaps her fall from power, even more than her rise to it, that made the public look at her with such disgust. She’d had unimaginable sums of money, but she had still lost everything: not just the cash or the career opportunities, but her health, her happiness, and her family. She had taken her 3-month-old son and fled her life in Mexia in part because she wanted to save him from the kind of childhood she had experienced: one marked by loss and instability, and the kind of pain that only oblivion could rescue you from. But money alone was not enough to allow her to break this legacy.

Looking at Anna Nicole Smith’s life and death — and seeing Daniel’s death not as a predictable footnote to a familiar story, but a heartbreaking final blow to a woman whose personal traumas had already been tabloid fodder for over a decade — means coming face-to-face with the realization that money can’t save us from ourselves, even if we have built a national mythology around this belief. If a poor girl is given all the money she could ever ask for, and still finds herself lost and alone, then it must be because she was stupid, greedy, wicked, bad. She must have squandered it. If we had what she had, we would use it right. We would escape poverty, escape trauma, escape loss. We would escape everything. That’s how money works, if you use it right. Accepting a different reality — one in which even unimaginable wealth cannot save us from ourselves — is just too painful.

In sharing the uncomfortable message, Anna was only carrying the torch that her husband had once passed to her. Separated by a seemingly unimaginable gulf of time and experience, Anna Nicole Smith and J. Howard Marshall were united in at least one way: They knew what it felt like to throw all the money in the world at the fundamental problems in their lives, and learn that money could never be enough.

Of all the things that made Anne Nicole Smith and J. Howard Marshall’s marriage remarkable, perhaps the most surprising is that she continued to speak fondly of him long after his death, after their marriage had made her career a joke, after his family had helped send her into bankruptcy, and after Marshall v. Marshall had made her life a living hell. Called on to describe their marriage, and what their relationship held for her, Anna described not the diamonds or the ranch or the shopping sprees, but something that may have seemed even more foreign to her than the money J. Howard Marshall threw at her feet.

“He cared about me,” Anna said. “He never looked down at me."

Sarah Marshall’s nonfiction has appeared in The Believer, The New Republic, The Best American Nonrequired Reading 2015, and The Week, where she is a contributing writer.