It was right around Halloween in 2012, just six months after I had come out as transgender. While finishing my junior year of college in Washington, DC, I was still getting used to life as a newly out transgender woman. And at the time, I was woefully insecure about how I looked — desperately trying to fit in, and yearning to be viewed as conventionally beautiful.

Society had made crystal clear to me that I was undesirable. The first time I heard the word “transgender” had been in a sitcom episode that mocked the potential for cisgender people to find people like me attractive. Every time someone expressed any interest in the gorgeous trans guest character — her identity still a secret to most of the main characters in the show — the laugh track would cue. And in the subsequent years, everything from popular culture to politics perpetually reinforced that message: Trans people are, at best, jokes, and, at worst, predators.

So when the good-looking blonde haired boy put his hand on my lower back during a party that Halloween season, I was flattered. When he kissed me that night, I felt honored. And when he made clear that he didn’t care that I was transgender, I was, in a word, grateful.

Perhaps he sensed my insecurity all along. Perhaps he instinctively understood the power dynamic — the royalty of his cisgender, straight male desires to the peasantry of my newly out transgender womanhood. Whatever it was, it started as consensual. That is, until he tried to escalate things after our friends had gone home, the party had ended, and we found ourselves downstairs alone.

Society had made crystal clear to me that I was undesirable.

“I don’t know. I don’t know,” I said when he continued to do something I didn't want him to do.

“I’m not comfortable with that,” I told him.

“I’d really rather not,” I resisted one last time.

But he kept going. He kept pressing. He was hell-bent on doing what he wanted.

You’re lucky he’s even interested in you, I thought to myself throughout the whole ordeal, having internalized those messages that told me there were few things more disgusting to society than my own body. And with him on top of me and not taking any variation of “no” for an answer, eventually I stopped protesting.

I knew I hated every moment of it. I knew I felt powerless while it was happening. I knew I didn’t say “yes.” But it wasn’t until the next day, when I was recounting the experience to one of my close friends, that I fully realized what had transpired.

This is the first time I’ve ever shared any specifics about that experience publicly. My heart races both reliving the encounter and sharing even surface-level details. And despite being out and open about nearly every aspect of my life as a visible trans advocate, it was only a few days ago that I first shared that I, too, am a survivor. Until then, I could count on one hand the number of people who knew.

On Sunday, my Twitter and Facebook feeds began to fill with people of all genders, particularly women, participating in the viral campaign that took off in the wake of the Harvey Weinstein allegations — by posting “me too,” they were demonstrating the pervasiveness of sexual assault and harassment. I tossed and turned all Sunday night, grappling with whether I wanted to share my own experience. While no one owes anyone else this information, I felt empowered by the bravery of so many exercising the power of their own voices in sharing their stories. It was a mass display of solidarity and I felt comfortable, for the first time in five years, to claim in the open my identity as a survivor.

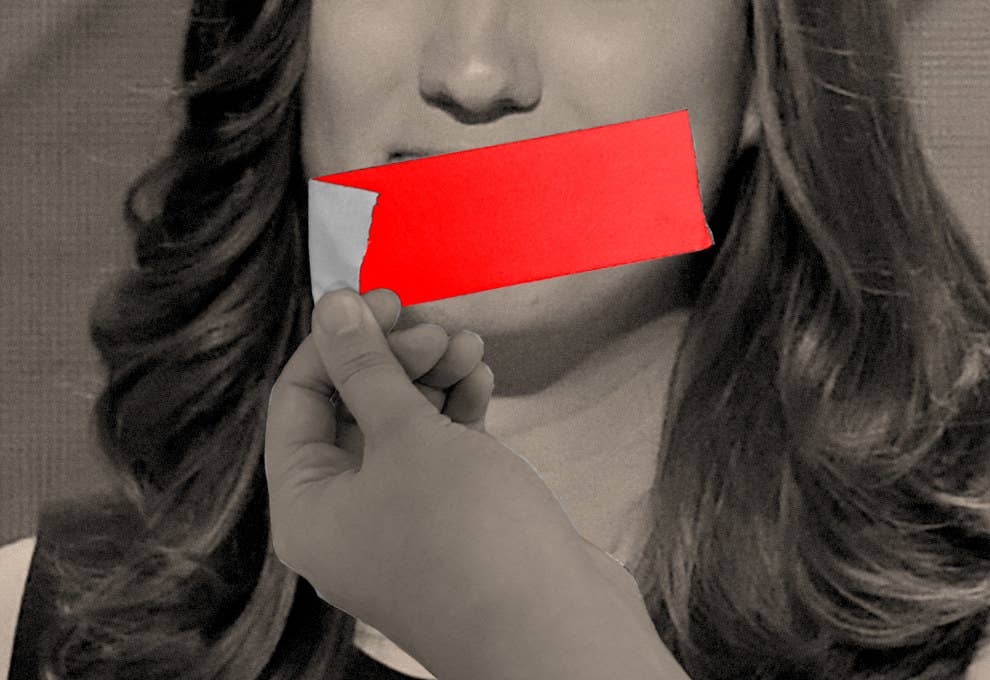

Like others, I at first chose to stay silent for many reasons. I certainly stayed silent because of society’s propensity to not believe survivors. I worried that if it took me a few hours to truly wrap my mind around what had happened, how anyone else would believe me?

I stayed silent because I knew that while many survivors are met with disbelief and doubt when they share their stories, trans survivors often also face a different kind of disbelief — one rooted in the perception that trans people are “too disgusting” to be assaulted. Alleged rapists and sexual harassers will sometimes insist that they couldn’t possibly have done what they’ve been accused of because the person accusing them is too unattractive to merit being assaulted. We’ve even heard that defense from our sitting president.

I also stayed silent because I feared that any story that “sexualized” me would undermine my voice as a woman and as a trans advocate. Women and trans people are already so often reduced to our bodies. I feared that people’s curiosity and invasive questioning would crowd out my voice on this and all other issues.

And I stayed silent because I knew that when people hear “trans person” and “sexual assault” in the same story, their minds pass over the reality of the situation and immediately go to the dangerous myth of the “trans bathroom predator.” Anti-equality activists have so stoked fears around protections for transgender people in restrooms, I worried that sharing my story could unintentionally reinforce support for anti-trans policies that actually foster violence — including sexual assault — against trans people.

While this is the first time I’ve shared my experience publicly, this wasn’t the first time I considered doing so.

Eight months after my assault, I found myself standing before the State Senate in my home state of Delaware. I was serving as the primary spokesperson for the soon-to-be successful effort to add gender identity to our state’s nondiscrimination protections in employment, housing, and public spaces, including restrooms.

I, and dozens of trans people of all ages, had just listened to hours of debate in the chamber, during which opponents of our civil rights had both subtly and blatantly compared trans people to sexual predators.

How dare they, I thought as I cleared my throat, ready to counter the offensive lies. These men — all men — were screaming about protecting people from sexual assault by painting trans people, many of whom are survivors like myself, as the threat.

Similar laws like the one we were pushing for had been passed in over a dozen states and a hundred municipalities without any increase in public safety incidences. In reality, 47% of transgender people report being sexually assaulted at some point in their lives. In some cases, trans people have been assaulted in and around bathrooms; they are not the perpetrators of violence in those spaces, but rather, overwhelmingly often, they’re the victims.

As I made my way through the facts and figures, rebutting these men’s disingenuous claims, I prepared to share that I was a survivor. But I stopped. I knew that too many people wouldn’t hear another word that came out of my mouth if I shared that piece of information. I knew that some wouldn’t believe me, either because they don’t believe survivors or because they couldn’t believe that a trans person like me could be a survivor. Or both.

I also knew that because of the combination of anti-gay and anti-trans sentiment as well as misogyny, however subtle, some people in the room and outside of it might have become so disgusted at the mere suggestion of physical contact with me — consensual or not — that they’d shut down. And all of my other points would be lost.

I knew that some wouldn’t believe me, either because they don’t believe survivors or because they couldn’t believe that a trans person like me could be a survivor. Or both.

This is how systems of oppression work: The violence, discrimination, and stigma I face as a woman compounds the violence, discrimination, and stigma I face as a trans person, and vice versa.

But the mere fact that I can safely share all of this now reflects my own privilege. Despite the continued experiences of harassment I face as a woman, as well as the threats I face as a trans advocate, I don’t have to work, live with, or see my abuser. I don’t have to fear his retribution.

My whiteness, economic privilege, able-bodied privilege, family support, and so many other factors shield me from some of the worst possible consequences — often fatal ones — that result from the toxic combination of misogyny, racism, and anti-trans sentiment. That poisonous mix has, thus far this year, left 23 trans people dead, and almost all of them have been trans women of color. Trans justice calls on us to combat the blend of prejudices that demean the lives and diminish the autonomy of another person.

Years ago, after two decades of shame and fear, I realized the power of my voice as a trans person. This week, through the bravery and solidarity of so many, I’ve finally found the confidence and power in my voice as someone who’s experienced sexual assault. For me, it’s been healing.

To all of the survivors, both those whose stories we know and the countless more whose experiences remain unheard, I stand with you. And to those who posted this past week, I hope in time that I can repay you for the help you’ve given this survivor with your courage in sharing those two powerful, but heart-wrenching words: me too. ●

Sarah McBride is the national press secretary at the Human Rights Campaign, the nation’s largest LGBTQ civil rights organization. She is the author of the forthcoming book Tomorrow Will Be Different: Love, Loss, and the Fight for Trans Equality.