A journalist told me a story about a man who recently bought an old house in a small village in the southwestern Polish region of Lower Silesia. It was a ruin of a place, untouched from the time of World War II, with missing windows and no roof. After the sale, villagers dropped by to tell their new neighbor the same story:

“There is treasure in the cellar of your house. Everyone knows it.”

“Why didn’t you look for it?” he asked.

“What for? Everyone knows it’s there,” they replied.

One night, over vodka, the man told a friend the local gossip. “Let’s look,” the friend suggested. They were tipsy now. They took a hammer and the bottle and went down to the cellar. They rammed the hammer into the wall and silver jewelry poured out of the hole.

“If you grow up in this region, you’re growing up with legends, with stories about treasures, stories that in every old house, in every old castle there is something, because there was,” Joanna Lamparska, the local journalist and author who recounted the story to me, explained. “There was a treasure in this house. Everybody knew that, but nobody wanted to check it because everybody was afraid that the treasure was not there. It's better to believe.”

On a drizzly afternoon in February outside the town of Wałbrzych in Lower Silesia, Piotr Koper strode purposefully across the thawing ground and came to a triumphant halt. “We were scanning this hill, first, in this direction,” the portly, ginger-haired construction company owner told me, pointing to a tree across from us marked “69” with orange spray paint. “Then another scan, this way to the bridge,” he waved diagonally to an overpass about 100 yards from us, “and then we checked here, exactly here, and that’s where it was.” Roughly 30 feet below our muddy boots was one of Europe’s greatest mysteries.

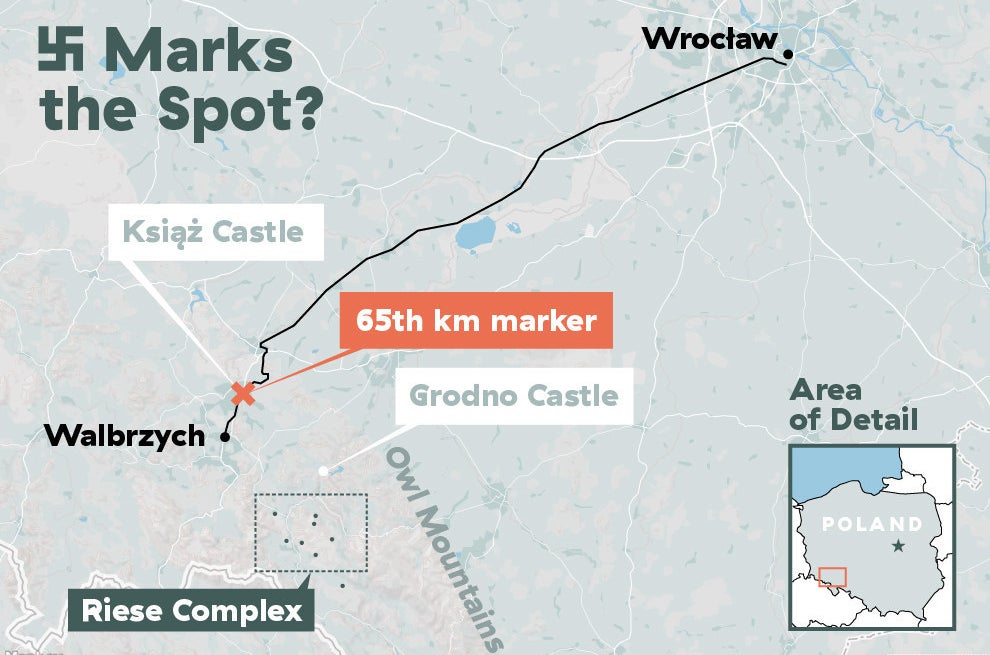

We were standing on a median strip, a kind of island between parallel railroad tracks. The tracks were sunk deep into the earth, creating steep cliffs of conglomerate rock on either side, except for at one spot, where there was a half-moon of dirt — Koper said this was the entrance to secret tunnels that were dug into the island we were standing on. According to Koper’s ground-penetrating radar (GPR) readings, under us were two long tunnels where Nazis hid a train at the end of World War II. The train would have curved off into the tunnels before the Nazis closed them, camouflaging their work with dirt and debris. Across from where we stood was a small black-and-white sign that read "65 kilometers," the distance between the town of Wałbrzych and the larger city of Wrocław to the northeast.

As the Nazis retreated from the encroaching Soviet army, they would have wanted to hide their most precious treasure. The train was loaded with gold bars, silver jewelry, stolen art, biological weapons, chemical weapons, advanced military technology, dead bodies, and even the Amber Room (a room with walls of gold and amber that Nazis looted from a palace in St. Petersburg and was never seen again) depending on whom you ask. Everyone from amateurs to the Polish government itself has been involved in the search for decades. Last summer, Koper, who owns a construction company, and his associate, Andreas Richter, a German genealogist living in Poland, claimed to have found it.

Koper and Richter said they researched the site secretly for over a year, bringing their three young sons here on weekends and evenings, telling no one except their wives what they were doing. They scanned the median with a KS-700, a new model of GPR Richter had imported to Poland from Germany. They found the tunnels and a train with tank turrets, verified their raw data with the German company, and submitted paperwork to the local government for permission to dig and claim the legally entitled 10% finder’s fee.

The announcement of their discovery set off a global frenzy. And for good reason: Printouts of their GPR readings show a train so clearly anyone could see it. Even the government threw its lot in. “I’m more than 99% sure such a train exists, but the nature of its contents is unverifiable at the moment,” Poland’s deputy culture minister said at the end of August. “The fact that this train is armored suggests there could be valuable objects inside.”

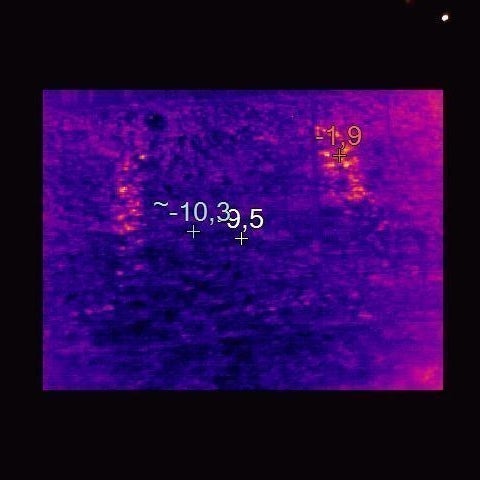

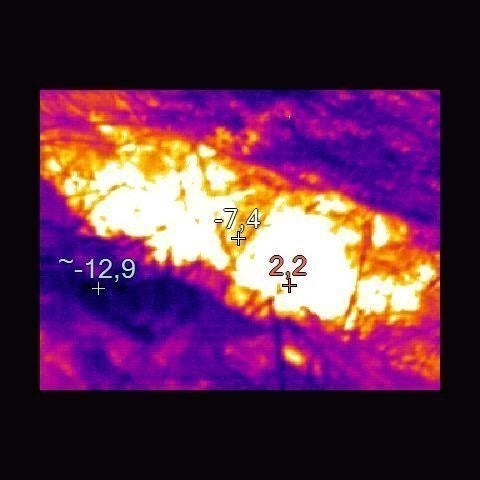

Infrared images from the 65th kilometer marker.

Everyone wanted a piece of the pie. Private sponsors flocked to pay for excavation. Tourists clambered, so many that the local government started blocking access to the site. The Russian government and the World Jewish Congress publicly jostled to claim the spoils. But jealousy, secrets, and promise of wealth make for nefarious bedfellows: Koper and Richter were accused of stealing the train’s coordinates from an 85-year-old great-grandfather. They were kicked out of their own amateur historical explorer society for breaking protocol and acting independently. The media hounded them after their names were leaked to the press.

Then, at a press conference in the middle of December, a scientific commission from AGH University of Science and Technology in Kraków, which had been dispatched to the site to verify the findings, made a declaration: “There may be a tunnel,” Janusz Madej, the head of a commission announced, “but there is no train.” The world lost interest. Koper and Richter’s sponsors pulled out. They were ridiculed — called impostors and drunks.

The announcement should have put an end to the hunt, but it did the opposite. Koper and his supporters have dug in their heels, standing by their own findings and citing new independent thermo-imaging research as proof. They are preparing to dig, convinced there is something the government is trying to hide.

The legacy of World War II looms large on the European continent, but perhaps nowhere more so than Poland, which was divided and occupied by Nazi Germany and Stalin’s Russia. After the war, Lower Silesia, which had been part of Germany, was given to Poland at the Potsdam Conference, but was occupied by the Soviet army after the war. Most Germans fled or were forcibly evicted to Germany’s new borders; a minority were allowed to remain in Lower Silesia because they had skills that arriving Poles lacked. Relations between the communities were strained. A shortage of facts and witnesses allowed legends to flourish as rationally as if they were truth itself.

As Poland fell into the Soviet sphere, the smothering dictatorship never explained anything to its citizens, and over the years, the myths took on a life of their own — many of them involved legends of treasure. Lower Silesia is home to the Riese complex, a massive Nazi bunker drilled deep into the nearby mountain range for no known reason. It is a place where rival treasure hunting groups work by moonlight, and where rumors of stolen secrets and mislaid treasure live in every crumbling Prussian mansion. Today, it’s not uncommon to see people calmly walking around the fields and nearby mountains with metal detectors and dowser sticks looking for Nazi gold.

I came to Lower Silesia to try to understand how people could believe the unbelievable. Why were people still looking for Nazi gold in 2016? Was it a realization of childhood fantasy, the lack of resolved history, or perhaps a natural reaction to the fog of war? Believing in legends and trying to verify them is at its core an attempt to find truth. Or was it about the Nazis themselves — finding their gold? What kind of people devoted their lives to this?

But during my time in Poland, finding treasure seemed tantalizingly possible. I was in a region where people didn’t need proof to believe a house had silver in the walls, but that belief turned out to be true anyway — almost as if the sheer power of conviction made it happen. There was the unshakable confidence in conspiracy — that greater powers were always thwarting explorers from getting to the truth. The science that disproved the myths was immediately contradicted by new findings that raised the same questions. All of this set in a bucolic landscape of constantly encroaching fog, looming mountains, and forests of old, dark pines.

And indeed, strange things keep happening along the 65th kilometer that no one can explain, while stranger things yet transpire all over Lower Silesia. The gold train is only the tip of the postwar treasure-hunting iceberg — a grander symbol of all that was lost and a beacon for what could still be found.

Tadeusz Slowikowski is the undisputed godfather of the Nazi gold train legend. I met him in his tidy apartment in Wałbrzych, surrounded by photos of his grandchildren and great-grandchildren. In the corner of the room, there was a large bookshelf full of multicolored binders of his life’s research — each one full of maps, diagrams, scrapbooks of photographs, and plastic sleeves of newspaper clippings. Slowikowski is 85 now, has diabetes, and is a little unsteady on his feet, but he remains single-minded, focused on the legend of the missing train.

In 1956, Slowikowski, then 25, was working at a coal mine outside Wałbrzych. One morning, as the miners waited for the elevator, a Polish worker strolled up and kicked an old German man. Slowikowski wasn’t too fond of Germans, but he couldn’t just stand by and watch. He punched the Pole and a fight broke out. A Pole defending a German — this was unheard of. The two men became friends.

Slowikowski spoke German fluently — a German nobleman had sheltered the boy during the war after his mother was sent to Auschwitz. The older man wept when Slowikowski told him about his mother’s murder. Slowikowski cried when the man told him about his son, who died fighting on the front. “I gained his trust and we became very close,” Slowikowski said. Sometimes the German invited Slowikowski home with him to share a meal.

One night, the man told him about a local German family the Nazis had killed before the end of the war. “Germans shooting Germans,” the old man said, over and over again. The man told Slowikowski it might have been because the family knew too much. They had seen the entrance to a train tunnel. As the Nazis fled, they had to make sure no one talked.

During the war, Lower Silesia’s largest city, Breslau, now Wrocław, was regarded as safe from Allied bombing. It became a place where Nazis shipped looted art for safekeeping. By August 1944, the Soviet army was approaching Lower Silesia and the Nazi leadership started to move art, goods, money, and archives to over 100 hiding places outside the city for safekeeping. Before World War II, Lower Silesia had over 3,000 small castles, more than the rest of Poland combined, Wrocław University history professor Tomasz Głowinski told me. Many noble families, thankful to take goods instead of German refugees, clambered to host the treasures.

Soviet troops encircled Breslau in February, and the city held for three months before capitulating. Germans hastily abandoned thousands of palaces and mansions. Many had hidden their savings inside their own homes, thinking they would be able to come back for them after the war, but after the land concession, they were not able to return. Newly arrived Poles found silver and gold in the walls. They saw riches they had never imagined before.

The territory quickly became known as the Polish Wild West. Stalin sent “trophy brigades” across his conquered lands to collect all manner of spoils to cart back to Russia. Between the secretive work of the Soviets and private looters, little is known of what was actually found and taken and what remained by the time the Polish delegations had unfettered access.

In the 1940s and ’50s, Polish government officials began to secretly hunt for their own treasure, but they found nothing. Locals were convinced the remaining Germans stayed to guard Nazi secrets, part of an insurgency called Operation Werwolf.

In 1950, Herbert Klose, a German veterinarian who stayed in Wrocław after the war, was investigated for practicing without a license and suspicion of anti-Polish attitudes. During his interrogation, Klose said the Nazi administration had asked the residents of Breslau to bring their valuables to the main police station for safekeeping. These valuables, as well as the deposits of Breslau’s banks, were taken outside the city by truck and hidden. Klose said he had been asked to help scout for locations to hide treasures. During the years of his repeated interrogation, Klose changed his story several times; he obfuscated his position in the Nazi regime. He said he accompanied the hiding expedition. He said he was just a veterinarian treating the horses they would use. He named locations; he changed them. One thing was constant: Klose said the loot left in December 1944 by truck. And so the legend of the gold of Wrocław was born.

The Poles found nothing, but the legend only grew — art, gold, hidden tunnels, trains, trucks. Even the government spurred gossip, asking locals to come forward with information and paying them in vodka. “There were many people coming to the secret police and claiming that they saw a mysterious truck or mysterious train entering the tunnel in the hill and it was never seen going back,” Sebastian Ligarski, a historian at Poland’s Institute of National Remembrance, told me.

There were rumors Germans had been told to turn away from their windows at certain times so trucks could pass without notice. Anyone who turned around would be shot. Whatever transport was used, it would have had to leave Breslau before the Soviet troops encircled the city. (This was not wholly outside the realm of possibility. In May 1945, a Nazi train had been seized by American troops in Austria — it contained gold, diamonds, jewels, fine china, and paintings.) Where could the gold of Wrocław or a train of valuables be hidden?

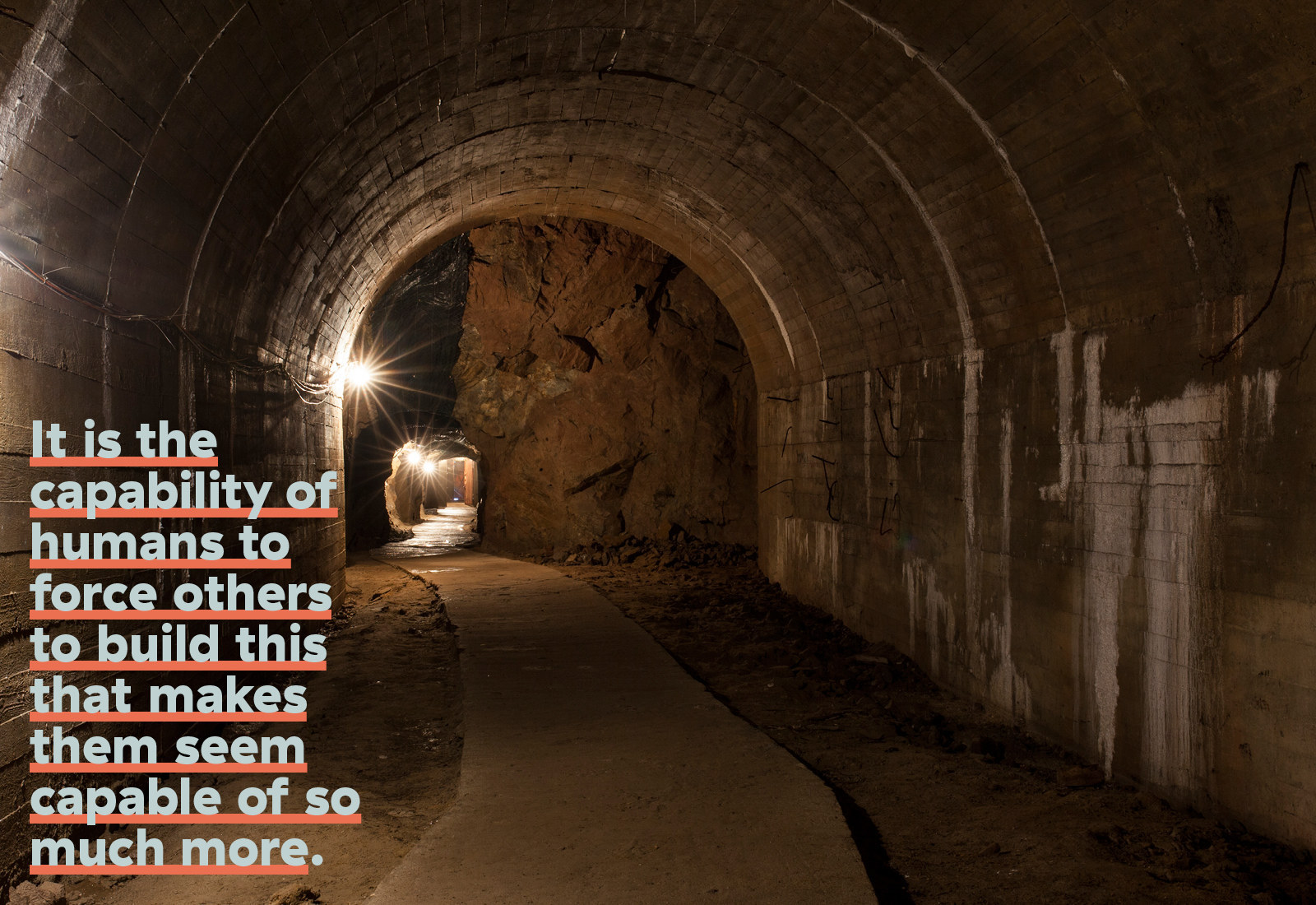

Naturally, suspicion centered on the mountain bunker network known as the Riese complex. In 1943, the Nazis broke ground on one of their most megalomaniacal projects (riese is the German word for "giant"). Thousands of concentration camp victims were forced to blast over four miles of tunnels deep into the Owl Mountains, forming a labyrinth of stone and concrete. One part of the complex sits 200 feet under a castle called Książ, possibly built to serve as one of the Führer’s headquarters. None of the seven parts we know about are connected to one another — each has a separate entrance.

Conquering Soviet troops first discovered the complex, but all the documents about it, including the construction blueprints, were missing. Since no one knew exactly why it was built, they guessed: The complex would be used to hide factories, chemical weapons, biological weapons, genetic research, atomic bombs, flying saucers, and a “wonder weapon,” and had 10 sections in total. A recovered 1944 message from Hitler’s minister of armaments and war production, Albert Speer, to Hitler implied construction had progressed much further than what is accessible today, fueling more speculation.

From May 1945 until June 1946, conquering Soviet troops set up shop in Książ. By the time the Polish authorities had access to the whole complex, all its entrances had been blown up and camouflaged. It was impossible to tell who had done what: Which entrances were closed by retreating Germans? Which by marauding Russians? Were there more sections as Speer's communication implied? Were they never finished? Were they hidden?

As a young man, Slowikowski, the miner, was obsessed with the Riese complex and made it his mission to speak to as many Germans about it as possible. “I collected lot of information from them that was connected with the tunnels and trains,” he told me over black tea and sweet biscuits, but he was specifically interested in miners. “A coal mine worker is the only person that could know about the tunnels and how they were made.” It was only after he retired that Slowikowski began to develop his theory about the gold train. He had heard about that same tunnel again from a German train stoker who told him there had been a high fence at the 65th kilometer line. One day, the stoker climbed on top of the train and saw an entrance to a tunnel and carriages standing next to it. At the spot, Slowikowski realized the family could have seen the same entrance from their upstairs windows, and so he decided they were most likely killed for knowing too much.

Slowikowski became convinced that the tunnel at the 65th kilometer held the key to the whole Riese puzzle. It would connect the Książ Castle to the rest of the complex. It could be the hiding place of a train, whose contents he didn’t know. But people were suspicious of Slowikowski fraternizing with Germans. To preempt being reported to the secret police, Slowikowski told me he went to the security services in 1974 and pledged to cooperate with the government. But mysteriously, Slowikowski said, the documents related to his search went missing in their custody. He got word people were out to get him. Four of his dogs were poisoned. Someone was trying to stop him from getting to the truth.

In middle of the 1970s, Maj. Stanisław Siorek, a high-ranking member of counterintelligence in Lower Silesia and a treasure enthusiast who had access to Klose's security file, produced a radio documentary about the gold of Wrocław to fish for more information from the masses. For the first time, everyone in Poland heard the region’s legends. The story grew — the legends became fact.

By the 1980s and 1990s, the government decided to enlist the Polish military to check places mentioned by Klose, along with a list of other rumored locations with Siorek at the helm. They hired scientists; they hired dowsers. There were roughly a dozen actions between 1982 and 1987, digging, drilling, exploding. Their only success was a buried container of coins a digger hit by accident under the cloisters of one of Europe’s largest abbeys, Lubiąż. The coins were mainly from the 18th century, unlikely to have been left there by the Nazis, but Siorek was convinced there would be more. A power struggle ensued. He was fired from his position and shipped to a psychiatric hospital. After a few days in the institution, he was released, but he was never reinstated. As a civilian, he fed information to journalists, founded a society of explorers, and continued to propagate the myths.

In 2003, Slowikowski finally got permission to dig. He found pieces of bricks and stones that didn’t belong to the hill’s geological structure. But after three days, he received a message from the government that work had to end to preserve the integrity of the railway line. “There is this invisible hand that is always stopping things from happening,” Slowikowski said, pausing to look at me through his bifocals. Over the four hours I spent with him, he tottered around the room, spreading so many maps, photos, and binders on the floor that it seemed impossible he would ever organize them again. His daughter flitted in and out of the room, bringing rounds of tea and coffee, but his wife never made an appearance. They were so used to him by now, to his stories, to the journalists who came to hear them, they just smiled indulgently. In 2006, his apartment was burgled, and he thought some maps may have been stolen, but wasn’t sure. He had spent most of his life searching for the train, popularizing the legend, speaking to anyone who would listen to him, and then Koper and Richter, who had walked me around the site, had put a claim in for the same location.

“The police told me to sue him and say that he stole my documents, but actually he didn’t steal them because I showed him the copies," Slowikowski told me. "But imagine how you would feel?”

Miłosław Krzysztof Szpakowski cast his flashlight along the smooth concrete wall of the bunker in Włodarz, one of the seven parts of the Riese complex. Włodarz has almost two and a half miles of known tunnels. Inside, 200 feet under the mountain, there is an almost religious solemnity, a graveyard of cement and rock, eerie in all the ways you would expect something built by the hands of thousands of doomed men. In some bunkers, the walls are narrow, finished with cement; others are wider with unfinished craggily walls. There are different levels, stairs, and drops. The floor is dirt and rock.

Szpakowski, tall, massive, and bald, looks like he could have been a drill sergeant. He was dressed in an olive uniform — a button-down with Włodarz insignia sewn on, cargo pants, and shiny, black leather lace-up boots. He had been a successful businessman, a big-time supplier of electrical cables to Europe, until he sold his company and used his personal fortune to lease and excavate Włodarz. Early retirement could have been so different — Szpakowski and his wife could be traveling the world, going on safari, but instead, he decided to spend his golden years mucking around tunnels near his hometown.

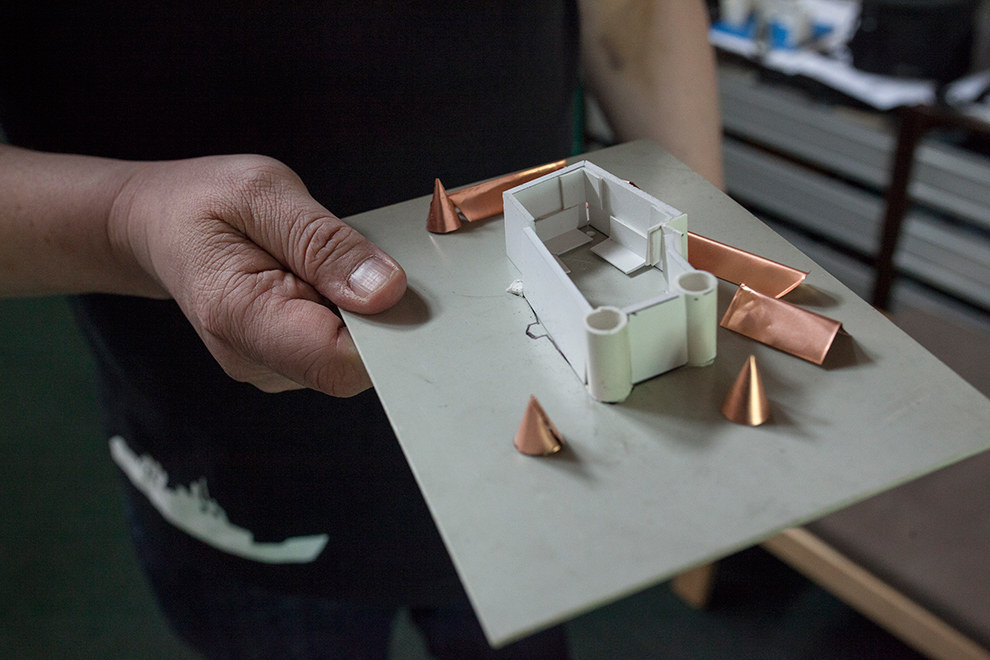

“I love this place; it’s so fascinating," he told me and my translator. "There is still so much to discover.” Szpakowski was explaining that he has located three missing parts of the complex. One of them was right beyond the beam. Inside them, Szpakowski supposes there is the gold of Wrocław, trains, maybe atomic weapons, or a secret city. He plans on finding it all. He had been researching his theory for years based on testimonies and recovered diaries. He thinks the three sections were completed, connected to one another, and hidden more carefully than the unfinished parts of the complex that we know. “We tested the wall with georadar and what I saw was the proof.”

Szpakowski paused and pointed his flashlight to the ceiling. Above our heads were four symbols carved in bas relief: a large Ukrainian coat of arms, an inverted swastika, a smaller swastika, and a strange small symbol that Szpakowski said was a rune. “It’s not easy to translate,” Szpakowski told us, “but you could say the meaning is: ‘Mother hides her other child.’”

Szpakowski found the carvings when his construction crews were removing the decaying wooden ceiling. They had been hidden for decades — a message from the slave labors of the Nazi regime. A chill ran through me.

We walked at least 20 minutes until we got to a tunnel half submerged in water, where we would need to board a boat to continue through the network. The ceiling where we stopped was over 30 feet. “Can you fit a train in here?” I asked.

“You could put two trains here,” Szpakowski told me, smiling. He believes there are two more levels under us — and possibly three trains in the undiscovered parts of the complex. “We have testimonies from witnesses and some documents about the train that came here. And trucks, that also came here with some bank deposits from Reichsbank,” he said.

We boarded the rowboat and Szpakowski pulled us along a line through the man-made caves. He could flush more of the water out, but tourists enjoy the boats. It was dark, lit in parts by hanging bare bulbs. Szpakowski explained he spent over $650,000 of his own money to excavate Włodarz. When he started, the tunnels were full of collapsed rock and submerged from natural drainage. All the entrances were closed off, exploded, crammed with rocks and debris; they descended almost 200 feet by line to begin clearing. “There was a moment when I was really close to quitting, because I thought I spent loads of money; it’s just too much,” he said. The first year, there were weeks where only a handful of people trickled in. But the summer’s gold train frenzy attracted more visitors than any previous year — 70,000 came in 2015. Thanks to the publicity, Szpakowski expects 100,000 this year.

Szpakowski told me it had always been his plan to make enough money and explore full time. In his words, it was a bit like being a “big boy” — the thrill of discovery, even the equipment explorers use, and what they find, tanks, guns, detritus.

“This isn't just a hobby — it’s that we are surrounded by all of it," he explained. "In the place where we lived, there are remnants everywhere.” The thrill is in putting together the pieces of the puzzle. “If you just collect information and documents and everything, you can create a picture of the whole and that is what fascinated me.”

As a former businessman, he had a theory about what happened with the gold train fiasco: private interests. Koper and Richter, whom Szpakowski considers comrades in arms against the AGH scientific commission, use the KS-700 georadar, the same type Szpakowski uses, and this has infringed on AGH’s stranglehold on the industry of treasure-hunting verification — as Poland’s premier technical institution, the commission has been called to check most of Lower Silesia’s confounding mysteries. “Before that they had monopoly for every request or application,” Szpakowski said. "And now unexpectedly, someone stepped into their specialization without asking them for permission with new equipment and other ideas."

For Szpakowski, it’s personal. The same commission turned up nothing when looking for the three sections Szpakowski said he found. “They declared that there are some anomalies but there is no underground city, nothing,” he told me. Szpakowski maintained this was because they don’t know what they are doing, so he decided to test them. He took the AGH scientist to a field where he himself had buried a large septic tank and said their GPR turned up nothing. So Szpakowski is plotting his revenge, vowing to return to the place where AGH found only anomalies with his own equipment and the press. “In the same spot, I will show that ‘Here you are: underground tunnels, shafts,’” he explained. “I will do the reverse of what they did, just because they really pissed me off.”

In February 2015, Poland changed its treasure-hunting law: Everything that is one meter underground belongs to the Polish state. Previously, there was just an honorarium, so there was no incentive to report findings. With the addition of a 10% finder’s fee, everyone flocked to put in applications. The local administration in Wałbrzych told me it’s examining 15 applications out of roughly 40 filed for permission to dig. Seven of those are Szpakowski’s.

I had heard others privately deride Szpakowski as a maniac for his applications, all the theories about trains, complex parts, underground cities, and hidden levels, a criticism he was well aware of. I asked Szpakowski if it didn’t seem like he had given everything up to wander around like a lunatic shouting from a soapbox about three hidden complexes and missing trains. He agreed, but told me he was the one who said the complex had been built in blocks and that no one believed him until recently. “I was very bravely talking about it for years, back then it was only theories; I continued on this path and I proved it. Now it’s common knowledge,” he said. He was convinced. And in many ways, he was convincing.

If from the outset the idea of missing trains, secret cities, and buried treasures seems outrageous, it takes only a few minutes in the Riese complex to begin to think anything is possible. Descending into the tunnels is an emotional quandary — equal parts awe and revulsion. It is the capability of humans to force others to build this, to commit the inconceivable cruelties we know they did, that makes them seem capable of so much more.

Between Slowikowski’s, Szpakowski’s, and other explorers’ claims, Lamparska, the local journalist, counted a total of 19 gold trains in Lower Silesia. There is no irrefutable proof for any of them, no documents, nothing other than the spoken word of sources with memories and diaries, few of whom have been named and even fewer of whom have come forward to publicly speak out, and then only in the case of the gold of Wrocław.

But it’s surprisingly easy to listen to theories about gold trains with a straight face. The people who tell you about them are believable first and foremost because they actually believe, added to this is a total absence of facts. Every time I sat down with someone to talk about legends, I would be convinced, but then I would leave and the glamour would fade. But in the end, because there is something unsettling, mysterious and ultimately morbid about much of everything in Lower Silesia, it was hard to actively disbelieve.

“We don’t have any evidence," Piotr Maszkowski, the editor-in-chief of Odkrywca magazine, told me. (The Polish word odkrywca loosely translates to “explorer.”) "We have this kind of thing between gossip, myths, urban legends. This is not the area of the facts. There is no historian in the region who would say, 'Yes, the story is fact,' but in every story there some are hints of the truth... There are thousands of those stories — about these German hidings and treasures, etcetera — and nobody found it until today and we will look for it until the end of our life.”

If there was anyone who could irrefutably disprove the legends — who has, in fact, made it their personal mission to — it’s Madej, the head of the AGH scientific commission. In the office of the head of the geophysics department at AGH, there is a little statue of a gold train Madej’s neighbor gave him as a birthday present. “This is the only one left!” he joked when I visited.

When Madej first heard about Koper and Richter’s research, he said he was outraged. “They are working in this unprofessional way and using unprofessional methods,” Madej told me. “I felt that I needed to say something.” Koper’s KS-700 uses its own software to interpret the data; the program produces beautiful three-dimensional readings, but Madej thinks the readings are the result of a software malfunction. He was so outraged, he wrote a letter to the local government offering to check Koper's research for free.

In November, the mayor of Wałbrzych agreed. Madej got together a team of eight scientists, and they sold exclusive rights to their research to the Discovery Channel, which, in return, paid for their travel and accommodation. They looked for six days, using a gravimeter and a magnetometer. “We used both methods and one of them, the gravimeter, showed no emptiness, and the other said there is no mass of magnetic field,” he explained. They also used a GPR. “It also didn’t show us anything.” And yet, he could not say there was no tunnel. Why?

“There is a tiny possibility that geology is wrong,” Madej said.

I asked Madej the question I really came to ask: How did he feel about being the man who crushed the dreams of explorers and the world? Madej smiled and told me he was not excited about that, but he’s not emotional about it either: “I’m a scientist who was studying a particular problem.” He continued, telling me it is not that the gold of Wrocław doesn’t exist, but that it just didn’t go by train — perhaps it left Breslau by plane or truck. “That’s why I’m very skeptical about this train,” he said.

Even the local government of Wałbrzych believes in the legends, but even more surprisingly in the conspiracy. Krzysztof Kwiatkowski, the governor of Wałbrzych County, told me he thinks only one-tenth of the Riese complex has been found. “It will be the biggest historical discovery in the world from the period of World War II,” Kwiatkowski said. But then why haven’t they started?

“There are higher powers that are always, each time are stopping us from starting,” he said. "Sometimes it is the other clerks, local offices that are telling us that we can't start drilling. Sometimes it's the National Forestry that is telling us we can't do that. And in the other cases, those are environmental groups. ... I don't know, who exactly is disturbing us. Is it an army? Our army? Or is it a foreign army? But I have this strong feeling that someone is disturbing us.”

The treasure-hunting community, which prefers the term explorers, is already skittish as hell. And frankly, they all hate one another. Treasure is valuable, after all, so few will reveal their sources — documents or witnesses — for fear they will be stolen, thereby making it impossible to verify them. “Relations are very bad,” Andrzej Boczek, another longtime explorer, told me. "Everyone wants to be the best, to find something, to declare that it was his."

I met Boczek in his explorer man cave, a small house he built specifically for treasure hunting on his property. “We can meet here in peace, without anyone listening to us. Of course, that’s important,” he said mirthfully, “but you never know, there may even be some bugs here.” The room had wooden panels and exposed brick, with deep-red leather chairs set around a green felt table. Boczek is tall with floppy blonde hair, blue eyes, and a tidy, thick mustache. His outfit matched the decor as much as the part. He was wearing faux military clothes, a dark green sweater and green scarf wrapped tightly around his neck.

Explorers in Lower Silesia work in small groups to keep their secrets. Boczek’s group owns all their equipment, diggers, cameras, and jeeps, even a GPR that he says they bought from the American military after it was used in Egypt. They meet every two weeks to strategize and plan missions. Boczek is sure he has been targeted. “Physically no one will get close to me, but if someone wants to harm me there is always a way,” he said, and showed me a bullet hole in his jeep’s door. He had been camping out in the forest, scouting for treasure, when it happened. His wife left him afterward. She didn’t want to indulge his obsession anymore. “When you’ll be over this craziness, I’ll come back,” she told him, but he couldn’t let it go.

Boczek took me into his trophy room on the condition I wouldn’t write exactly what his treasures were, so all I can say is that they are stunning. “How can you leave things like this?” Boczek exclaimed while pointing to mounted objects, pulling more off shelves and out of cabinets. “How could you sell this? I love this!” For all the explorers I interviewed, it didn’t seem to be about the gold itself. They never talked about the money.

Boczek caught the treasure-hunting bug young. He grew up in Lower Silesia back when there were still prisoners’ belongings, striped shirts and shoes, littering the forest. He climbed into the Riese complex as a kid. Back then, everything was still sealed off and wild, and they carried stones out of tunnels by hand, one by one, driven by curiosity. “That was a watershed moment for me,” he said. Boczek started searching for answers: What did they build all those tunnels for? How many prisoners worked there? How many people died? “I was searching for all of these details. After, as the years were passing, I felt that this hobby was starting to be my passion. It was like evolution.”

Boczek’s biggest discoveries were unearthing a collection of World War II weapons from underneath a stadium and opening an empty underground tunnel in Soboń, before the government shut it down. “Right after, for no reason, unexpectedly, this place, this forest became national park, where you can’t drill anything,” he said. “So a question was born: Why at this time? Who cares to make sure this stays untouched? I think it was some order from above.

“There are some secrets, mysteries that we still can’t know. Until today here, in this area, there are people who are called guards, and they are keeping the secrets of this region," he said, referring to Operation Werwolf. "Maybe there are a lot of corpses of people that were killed here? Answering all those questions is duty of us, of explorers.”

But Boczek does not believe in the gold train, at least not where Koper and Richter say it is. He has a different source and location — one of the 19 Lamparska counted. “This closed zone is in a different part and it’s confirmed, but I can’t tell you where it is.” Boczek said. When I asked if he was planning on excavating, he sat silent, only blinked and smiled.

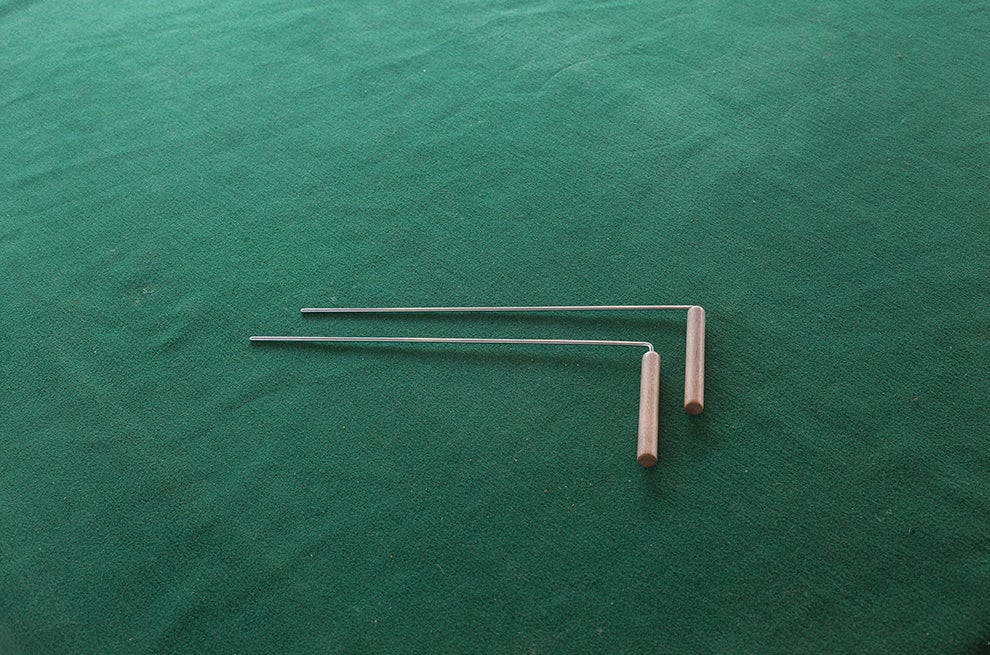

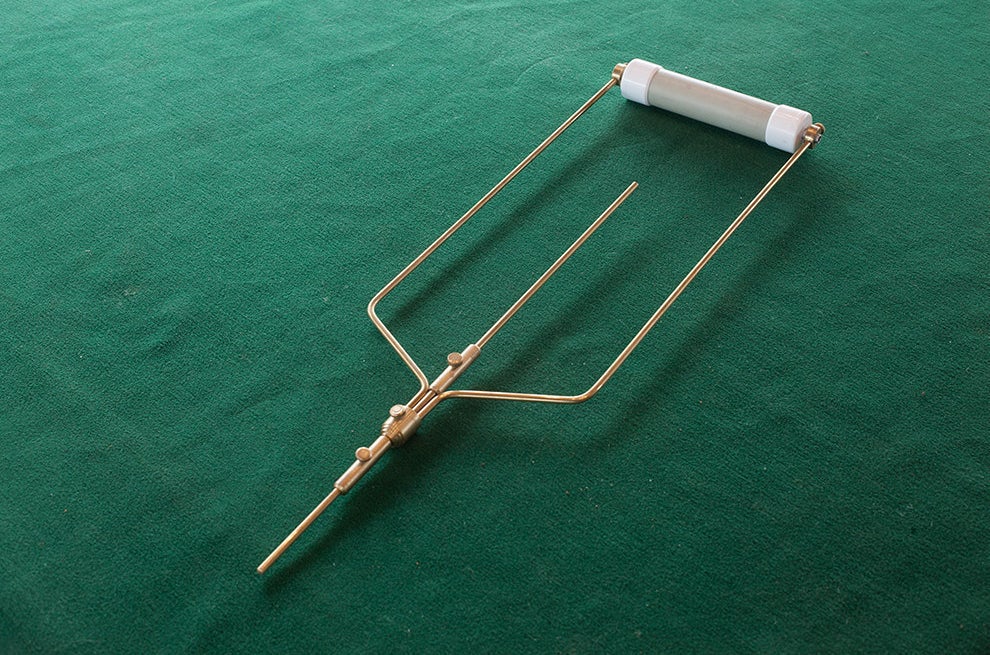

Boczek showed me how he puzzles together locations of treasures by comparing old maps to the present day, and by anomalies in the landscape, but his secret weapons in the hunt are dowser sticks. “They are gift from the very well-known Polish fortune-teller,” he told me, holding two thin metal sticks with wooden handles. He asked me if he could run a simple test to prove they worked. “I can tell you how much money you have on you,” he told me, “more or less.”

I agreed, and Boczek focused on the sticks, which spun slowly in his hands.

“About 350?”

I had 370 złoty in my wallet.

“I told you they are full of power,” he said.

Łukasz Orlicki cranked up the volume as the opening guitar riff of Creedence Clearwater Revival’s "Fortunate Son" streamed from the speakers of the Odkrywca magazine team's Land Rover. There were five of them in the car. Orlicki and Maszkowski are employed full time at the magazine — Maszkowski is the editor-in-chief, and Orlicki is the head of explorations — and have been working there for 12 years. Maybe because treasure hunting had become their job, or maybe because so many searches had turned up empty, both were jaded. “I’m the most cynical person you’ll meet,” Maszkowski told me when we first met. He seemed genuinely apologetic. Crammed in the backseat were Pawel, Maciej, and Przemek, three volunteers who often come along on weekend treasure hunts. Conversation ceased as we bumped along the dirt road, and the guys in the car belted along in unison: "It ain’t me! It ain’t me!" At the steering wheel, Orlicki pumped his fist.

It was just after 10 p.m. and the guys had grabbed some beers as we headed to the Owl Mountains to enter another tunnel in the Riese complex — one that isn’t open to tourists. Earlier in the day we explored Grodno Castle, a crumbling 12th-century testament to Lower Silesia's woeful past — the gray stone façade is patched with red brick, the grand archways are now skeletal, and most of the windows are missing. Teams of men (and it was always men — I asked) with different georadars took turns mapping and walking across the castle ground. They discovered empty space behind the fireplace, under the kitchen, under the crypt, and behind an outside wall — but no reachable treasure.

But by now, the guys had ripped off their Odkrywca insignias and we were all private civilians, trespassing — this is the nature of most treasure hunting. The entrance to the tunnel was gated, so we had to climb through. We donned hard hats and vowed to be silent; the reverberations of our voices could send the unstable rocks crashing down on us. Unlike Włodarz, which has been sanitized for tourists, there were no supporting beams for the ceiling, no lights. Orlicki guided us by flashlight. We came to an intersection and scrambled over some rocks, then another intersection where each of the three paths forward was full of boulders that had fallen from the shafts above them. There could have been anything beyond them. Anything.

We drove back to the castle in the moonlight to put a camera in one of the outside walls to see if there was a chamber behind it.

Maszkowski had the honor. He threaded it through a small hole and jiggled. Everyone laughed in the darkness. Przemek held a flashlight. “Can I pull it out?” Maszkowski asked his audience. “Yeah, go on, sure,” someone answered in the darkness. But the camera didn’t pick anything up. There was soft sand in the hole. Someone handed Maszkowski a plastic pipe to probe inside cautiously.

“Go on, go on!” the group egged.

“What do you think is behind here?” I asked him.

“A treasure, I hope!”

Maszkowski kept pushing the pipe. “The soft structure is deeper; if we had a metal stick or something, we could…” He trailed off. He thought he hit another wall. There was nothing there after all.

Without pause, they moved on to the next anomaly. The group split up and fanned out across the grounds. I lost Orlicki as he climbed into a drainage pipe.

Meanwhile, Maszkowski approached the night watchman and asked him for a tour of the crypt. He listened attentively as the watchman told him about the one night a year crows fly in a circle around the castle and squawk as if they are talking to one another. It happens on the same night every year. Strange things happen in Lower Silesia. Maszkowski nodded solemnly. Earlier the guys had told me that in order to get information, they had to listen to every story, no matter how bizarre. They wanted people to feel free to come back with more, no detail was too small. Much of treasure hunting turned out to be cross referencing witness testimony, meticulous archival research and guesswork.

The watchman showed him a photograph of the castle prior to World War II — coats of armor, chests, and paintings lined the walls — and mentioned that he himself remembered it that way from the 1960s and ’70s, when he played there as a child.

“This is an incredible situation!” Maszkowski exclaimed. “It means that after the war, nobody stole it. It’s completely amazing, it’s almost impossible!”

As cynical as he claimed to be, Maszkowski couldn’t seem to hide his enthusiasm. It hit his face all at once and spread like a tremor through him. He bounced through the foyer, full of energy, almost jumping out of his skin. If no one had looted the interior trappings throughout the ’70s, perhaps no one had touched what might be hidden further inside. It’s not really about the treasure — it’s about the possibility. There’s a magnetic energy to discovery.

“The fact that we are free to do things here, like making a hole with this pipe, it’s quite exciting,” Maszkowski said. “It’s an old castle with lots of great stories that I haven’t read yet, maybe that’s why I’m so optimistic now. It’s a grave sin that I haven’t read about it." Imagination is endless.

During World War II, people came to visit the grounds. They lived here; Orlicki didn’t think anyone hid anything here. But why couldn’t it have been another place where the Nazi leadership moved art, goods, money, or archives from Breslau?

Orlicki indulged me. Why not indeed. Belief or not, it had been a good day. “We found stuff we only heard in legend, we managed to confirm those legends,” Orlicki summarized. What’s inside, they just don’t know.

Faith in the gold train at the 65th kilometer is now sustained by an unlikely source: a man to whom it was really a children’s tale to begin with. Michał Banaś, a researcher at the Institute of Geological Sciences at the Polish Academy of Sciences in Kraków, met Slowikowski when he was 11 years old, and it changed his life. He was on vacation with his parents when he met Slowikowski in a parking lot and heard his tale. Banaś was fascinated. Most of his family is in architecture, but after meeting Slowikowski, Banaś decided to study geology.

In the last few years, Banaś has worked extensively with thermo-imaging. He had stopped believing in the gold train ages ago and he’s not convinced there’s any more to the Riese complex than meets the eye. Instead, he suspects Speer’s communications with Hitler are the result of a money-laundering operation in which Nazi officers reported progress further than they achieved so they could pocket the cash. As for Koper and Richter’s science, Banaś is disdainful: “Absolutely, totally amateur equipment.”

Banaś was in the area in February for other research and on the way back, he and his colleagues decided to stop at the famed 65th kilometer and have a laugh. He took out his thermo-imaging camera and pointed at the hill. He couldn’t believe what he saw: There were two points, holes really, that were a completely different temperature than their surroundings. Banaś was so confounded he decided to spend the night and look again. “I couldn’t believe what I saw the day before,” he told me, flipping through the photos on his office computer. “I made this panorama in the morning — a bigger photo with more background, and my results were the same: Those strange things were appearing in the same places.”

“What does that tell you?” I asked.

“I don’t know exactly what was inside," he admitted. "The only case where we can observe this similar situation is when we have an underground cave and the cave is pushing warm temperature outside." So what on earth is going on at the 65th kilometer? Banaś couldn’t say, only that “it means that something unusual for sure is there.”

As we clicked through his thermo-imaging photos, Banaś seemed as confused as I was. “Here is natural outcrop,” he said, pointing to the conglomerate cliffs around the embankment, and then to the supposed entrance of the tunnel. “This is not natural. This is something artificial. But I don’t know what this is.”

“I believe Banaś," said Maszkowski, who had also called Koper and Richter's theory "absolutely bullshit." "He’s a scientist. He was skeptical before. He has experience with thermo-vision before. So where he sees an anomaly, there must be something. If he doesn’t understand those anomalies, that’s very weird.”

Back at the 65th kilometer, it was starting to rain. Koper and Richter had categorically denied taking Slowikowski’s information and said they had their own witness testimony that pointed to this exact location. Koper told me he hadn’t always believed in the legend, and gestured to the physical anomalies that convinced him: three electricity poles that he said should be in a straight line, but one stands askew with mismatching isolators. In his opinion, it was moved to mask the entrance to the tunnel. There are at least 10 foundations for what he thinks was a masking grid to prevent Allied planes from noticing the tunnel’s construction. Then there is the geological makeup of the hill.

Koper pointed to the mysterious accumulation of water at the site of what he said is the tunnel’s entrance, where Slowikowski told me green grass grows even in the harshest winter snow, and indeed it is at those points where Banaś’s thermo-imaging flares up temperature discrepancies like the northern lights.

Everyone I spoke to about the gold train had been caught off guard by the announcement last summer. What had been a legend that should have died with the man who propagated it had taken on a new life that reverberated across the world, and in its retelling had somehow come to encapsulate all the region’s other legends literally inside of it. The belief of one old man became the cause of thousands, inspiring the next generation of explorers in love with the fantasy. In Poland, sales of metal detectors went up, subscriptions to Odkrywca rocketed, tourists shouted down guides at the Książ Castle for suggesting the train didn’t exist. “It was the same situation with this jewelry house I told you about,” Lamparska explained. “We know the train is there, but we don't want to look for it because the train is not there.”

I tried to engage everyone I met in the bigger meaning behind the legends, the bigger point of the hunt for the train. None of the men I spoke to could articulate exactly what it was. All of them talked about the personal thrill of discovery — of being a boy with an adult man’s access to equipment, the thrill of uncovering something someone was trying to keep a secret. All in a place where mystery lives in every house, where treasure has indeed continued to pour out of the walls.

There was something peculiar and unsettling about Nazi treasure hunting, both morbid and fascinating. And something about Nazis in general that repels and attracts us simultaneously. But to continue believing in the legends, to want to believe in them as the whole world did when the gold train was announced, was perplexing. The Nazis were capable of everything our society pledged to never allow again — if you systematically exterminate millions of humans, surely you can hide one gold train. Were we still looking for closure? And so, really, why didn’t the government just dig everything up and settle it once and for all?

Koper suspects that the government has already looted the train and doesn’t want to explain itself, or that there’s noxious gas inside that the government also doesn’t want to be responsible for unleashing, or, more simply, that the government just doesn’t want to admit its failures. “It’s impossible that just two normal guys came here and they just found something, without any connection to academic institutions, without any connection to the general restorer, without any political background,” Koper said. What he really wants are private sponsors to fund excavation. The two men are selling gold train lighters on their website to raise money for the dig.

I asked Koper what he would tell the people who didn’t believe him. “What we do is not a matter of faith; we made one of the biggest investigations in Poland,” Koper said as we walked away from the tracks. “It’s not a matter of faith, it’s a fact.” ●