The court system is one step closer to deciding whether retailers should compensate store workers whose call-in shifts are cancelled at the last minute.

Victoria's Secret and lawyers for two of its ex-employees finished submitting briefings this week to a federal appeals court, as part of a lawsuit centered around on-call scheduling. The core question at hand is whether workers whose shifts are cancelled by phone — often within hours of starting time — are covered under a California law that requires employers to pay staff who "report for work" but are sent home early. Retailers contend the law only extends to people who physically show up to work.

Victoria's Secret argued in its Feb. 8 briefing that "not once in its more than 70-year history has the reporting time pay regulation been interpreted to require employers to pay employees for calling in before showing up for work."

Employees "must do more than make a phone call from a distant location

two hours prior to a 'call-in' shift in order to 'report' for work," they said. Workers "could be in any state of unreadiness at the time of the call: they could be in their pajamas, far away from the workplace, actively engaged in some other pursuit, or attending to some other commitment."

But the plaintiffs say the call-in system has the same effect as sending people home after they physically show up — and is used by retailers for the same reason.

"The whole purpose of the reporting time law was to regulate over-scheduling practices," David Leimbach, a lawyer for the former employees, said in an interview. Whether it's physical attendance or a phone call, "the principle is the same — you're over-scheduling employees with a frequency that exceeds your staffing needs for optimal employee overhead costs," he said.

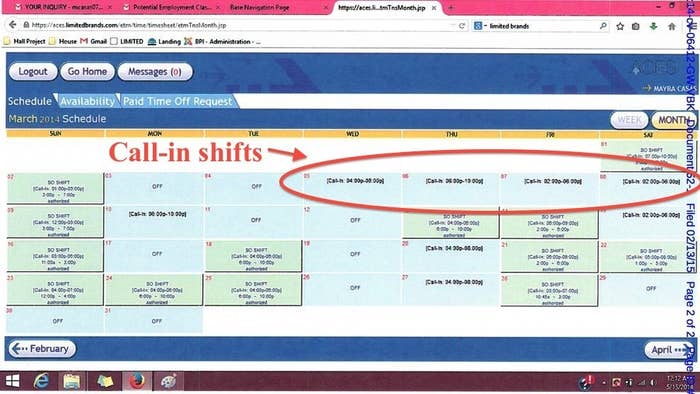

Call-ins, which often appear alongside regular shifts on store workers' schedules, typically require them to phone in two hours before start-time to find out if they're needed or not.

If the answer is yes, they must go in, meaning they can't commit to college classes, child care or other work for the time covered by the shift. But if they're not needed, they go unpaid. Arranging childcare and eldercare around these "maybe" shifts, which can eat up 20 hours of a week, can wreak havoc on the lives of low-wage employees.

Retailers have come under fire for this kind of scheduling in the past two years, especially after the New York State attorney general began looking into the practice last year. After a BuzzFeed News story about such policies and the lawsuit against Victoria's Secret last June, the lingerie chain ended the policy. Afterwards, Gap Inc., Urban Outfitters, Abercrombie & Fitch and J.Crew also announced plans to stop using call-ins following conversations with the New York attorney general.

The "report for work" question before the appeals court, which arose from a class-action lawsuit filed by former Victoria's Secret sales clerk Mayra Casas in July 2014, could remove the financial incentive for retailers scheduling employees this way in California. It could also influence rules in eight other states, plus Washington D.C., that have similar laws around "report for work" payments.

The question made it to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit after a California district judge in the Casas case was stumped over whether the phrase "report for work" requires physical attendance at a scheduled start time — the law doesn't specify. While he concluded it does require physical attendance and dismissed the call-in reporting time claim, he permitted the employees' lawyers to appeal that decision.

The appeals court, which covers multiple states including California and Arizona, granted the petition to appeal last summer. With briefings in, the next step is waiting for the court to set oral argument dates or potentially involve the California Supreme Court, then wait for a definitive interpretation of the rule.

In filings related to the lawsuit, Victoria’s Secret “conservatively” estimated that if the company were required to shell out at least two hours in wages for every call-in shift that a part-time employee in California wasn’t permitted to work between July 2010 and August 2014, it would cost $25.1 million. And that's just in a single state across four years.

Even though Victoria's Secret and its sister company Bath & Body Works stopped using call-in shifts last year, Leimbach said it doesn't affect the appeal.

"We're certainly thrilled they stopped using the policy as that's one of the fundamental goals of this case, but there's nothing stopping them from doing it again if they so chose," Leimbach said, noting he's seeking a permanent injunction against the practice. The other issue is getting former Victoria's Secret employees "compensation for having had to comply with this policy and getting denied the opportunity to earn those wages in the first place."

"This is not just some little inconvenient scheduling practice," he said. "This is fundamentally usurping people's personal autonomy, their ability to earn a living wage."