Her sandals are Rainbows. Her tips are French. Her shorts are improbably yet un-self-consciously short. Her hair’s blondeness has been chemically emphasized and hangs to her lower back. Her eye makeup is smoky and her T-shirt baby blue. She is lovely and she is brilliant and she is terrifying. She is 17, I'll learn, for another two days. I lean down the row of chairs and mutter to someone, “What’s her name?” and eyebrows lift knowingly.

“That’s Summer.”

Though it's been a decade since I've seen one, and I've only been watching her for a few minutes, it's clear: Summer is a mock trial star.

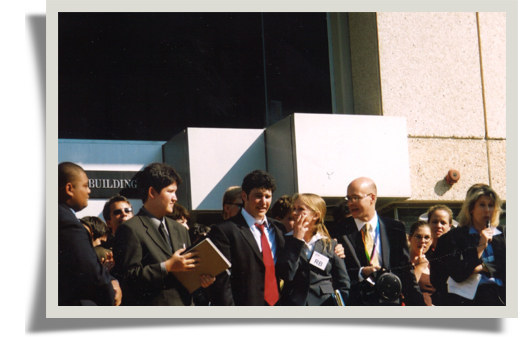

I'd silently entered and sat in the back of this hotel conference room as Summer was cross-examining a witness from the other team. His face is red and speech spitty. She paces back and forth as she delivers a question, then another, at him, like a tennis pro humoring a novice with a game of pickup. The back of her shirt says “California State Champions.” The team she captains, from Redlands High School east of San Bernardino, won California's competition back in March. Now, two months of unending stress and preparation later, they’ve arrived at this year’s national competition, in Raleigh, North Carolina, hoping to do the impossible: Be the best high school mock trial team in the nation.

Mock trial is a competition involving two teams of students pretending to litigate opposite sides of a legal proceeding. It's played in law schools and colleges and high schools. (And some middle and elementary schools too.) Nationals actually starts tomorrow, Friday; what I've been watching is just a practice round, hence the street clothes and not yet being in a real courtroom. California's team has nonetheless been in here since Tuesday scrimmaging against other teams. This is their second practice fake trial of the day.

It ends soon after and the kids shake hands, smiling broadly, and gather their binders and legal boxes. In the next room, a North Carolinian–themed welcome dinner has been laid out and mock trialers and parents from other teams, all wearing their own state championship T-shirts, are scooping mac ’n’ cheese and ribs onto heavy plates.

We sit in a ballroom at banquet tables. Summer’s parents tell me she’s going to USC next year, that she was in fact recruited by that school’s mock trial team.

"Have you ever seen mock trial before?" someone asks me.

"I have," I say, and pause, looking at a baked bean on my fork.

A series of white men address the 700 students who've come to this year's competition: someone in charge; a justice from the North Carolina Supreme Court; someone else who tells the kids what time they’ll post the first-round matchups, and announces, “The pin exchange will begin right after the meal!”

By the energy in the room, though, the pin exchange cannot start sooner. Already the volume is rising as mock trialers begin standing from their tables and approaching each other and, reaching into plastic bags of pins that bear the names of their home states, exchange them, all laughing, all smarts and nerves. This is an opportunity to figure out who's here and who seems good. When the competition begins tomorrow morning, the teams will no longer be able to disclose which states they are from and will instead don large three-letter codes on their blazers (the idea being that this way judges aren't tempted to favor their home states). California's pins are white and say "I HEART MOCK TRIAL" and "CALIFORNIA" with the URL of the organization that sponsors their state's competition.

I move toward the exit and the North Carolinian Supreme Court justice seeks me out and shakes my hand — he seems to have learned I am a reporter. He dives into a speech and I try to focus on him despite the frenzy of pin exchanging around us.

“If you see a real trial and you see the kids have a trial, you’ll be surprised at the quality of advocacy,” he shouts, and recites a couple of lines of the North Carolinian state constitution off the cuff. “This is what the rule of law is about, treating everybody the same,” he says.

He continues: “So many of these kids are going to be doctors or accountants or engineers. This will be their exposure to the law before they become jurors.”

We are interrupted by a clown.

“Start moving downstairs!” says the clown. She's wearing striped kneesocks and pigtails. I don’t know why there’s a clown, and I lose the Supreme Court justice in the mudslide of teenagers now making their way down the staircase, teenagers who are handing one another not only pins, I realize, but Zapp’s chips, bags of mini Oreos, Sun Drop sodas. I see a girl with puka shells and realize, It's the team from Hawaii.

Here’s the thing I’m not saying. The thing I’ve gotten good at not saying, though in this context, among these people, I probably will say: I’m not attending the High School Mock Trial National Competition as a journalist. Not just a journalist, at least. Ten years ago, when I was a high school senior, after my team won California’s state mock trial competition — which was itself huge — we went to nationals, held that year in Charlotte, North Carolina, and we won that too, making me team captain and lead attorney of the best mock trial team in America and, arguably, the world. It was, certainly at the time and for a long time after, the most significant achievement of my life.

Three months later, though, I got to college, where everyone, it seemed, had been truly great at something that was now essentially meaningless. I found myself embarrassed whenever I would think about the win. Sometimes I couldn't help but talk about it. A guy once listened to me talk about it and said, “That was a really long story.” At some point, I stopped talking about it. At some point I started thinking about what this activity was and wondered, why had I cared so much about competitive fake law? Then I looked it up and saw that for the 10th anniversary of the win, the competition was being held again in North Carolina.

Outside, clanky circusy music plays and there are several other clowns performing tricks — I don't know why. The kids are more interested in their pins and their phones and each other. The day has cooled, and between the tall, glass-sided office buildings of downtown Raleigh, above the Jimmy John's and the Twisted Mango, the sky is blue whipped with white. A Hacky Sack circle has formed. Two girls shriek as the track changes to “Chandelier.” Two kids from Texas pose for a selfie and pause as a teammate rushes to join, and another, and another, like birds landing on a wire, until eventually it devolves into yet another entire team photo. Some of the teens look like adults, leggy and poised and even fashionable, and others don’t — small and greasy, their motions uncontrolled, especially now as they stuff handfuls of yellow cotton candy into their braces. There’s a commotion, and I learn that a skinny boy on the California team has gotten a girl's number.

I meet another senior on the team, whose name is Canyon Frost. He is blonde and his teeth are white.

“We’re so proud to be in North Carolina,” he says, nodding to my notebook. I start writing down what he’s saying. “We have a pretty decent shot,” he says, explaining that it’s good they’ve been scrimmaging for two days, not just one day, as some other teams did. “We’re professional now." He’s going to the University of Chicago in the fall. Physics, he says.

“Do you not want to be a lawyer?” I ask, a question I used to get all the time. A question I grew to hate. ("I don't think so," I'd answer, and then say, "Yes, really" and "No, I don't know what I want to be instead.")

“I don’t think so.”

Which isn't to say he doesn't love mock trial, he goes on. He's done mock trial for all four years. And his team has worked so hard, for so long. It is a feeling I know well.

“What a perfect note to end it on,” he says, and pauses, looking around the pedestrian mall, at the other mock trialers, that last obstacle: “having won nationals.”

I didn't have any discernible interest in law before I auditioned for mock trial as a sophomore. I did theater. I had few friends. I was good at school and came from a screaming house. I didn’t yet have a license or a car or the freedom that those entailed. (My family lived several miles from my high school, over a mountain on the coast.)

One day, I was sitting on my backpack waiting for the lunch period to pass when a guy, a senior — the kind of senior everyone knows, the kind of senior whose shitty car everyone knows — approached me. "You," he said. "We're going to lunch." I had never spoken to him before. I didn't know how he knew to approach me, but he had evidently been told to recruit me for mock trial. He told me to audition for the team. I didn't really know what mock trial was, but I did what he said.

I remember the first time I saw David Vogelstein, our team's attorney coach. (Teams have multiple coaches, some of them attorneys volunteering their time, as well as teachers.) David was long and lean and wore an olive suit. I remember he interrupted me during my audition with a raise of his spindly hand. There are many things you notice about him when you meet David, but perhaps most striking is his voice. It's gravelly and emphatic and its vowels betray the New York of his youth.

“Um,” he said, putting down one finger. “Um,” he said again, putting down a second, and then counted off eight more "um"s. “Ten. You’ve said 'um' ten times. Next time you talk, I don’t want to hear a single um.”

“Yes,” I said, a puddle.

“Yes, your honor,” he corrected.

"Yes, your honor," I said.

I was convinced I hadn't made the team, but I did. I was cast as an attorney — attorney roles are generally more sought after than witness ones — which I later learned was rare for an underclassman.

Here are the things we knew about David: His parents had fled Hitler's Germany; his dad later returned and fought. David and his wife went on their first date to Woodstock (her invitation), and they've been together ever since (now 46 years). He broke into a draft center during Vietnam and was sentenced and did a few days in solitary. He'd practiced criminal defense in our county, Marin, for a long time.

Every year he coached our high school's mock trial team, they’d won the Marin County competition, besting the handful of local teams, and never without a fight. It was a seven-year streak when I joined. That said, they'd never yet won state. This was no knock on the team; today 475 teams participate statewide in California, and 34 go to the state competition, making it one of the biggest and toughest mock trial competitions nationwide.

When he wasn't in a suit, David often wore tie-dye and cutoff tees and gold chains and those glasses that are supposed to change in different lights but usually produced the effect of him wearing sunglasses inside. He drove a succession of loud, intimidating black Mustangs. He played basketball at the Y. He was the kind of Diet Coke drinker who was seldom without one. He wrote big notes — ELEGANCE. BE A HUMAN. REASONABLE DOUBT — on the whiteboards of the classrooms we sat in practicing several nights a week for most of the school year.

During practices, witnesses memorized their statements and honed their characters as attorneys wrote their direct and cross-examinations. David would give lectures about the law and about life. Sometimes the room swelled with rowdiness and he'd get real mad. Sometimes it'd feel like we were a mess, like we had nothing right, like we would be humiliated come competition day and ruin our school's county competition streak. On our lowest days, we'd run the mock trial equivalent of drills: standing up one by one and stating our names as clearly and professionally as possible, as we would have to do at the very beginning of each round of competition. The slightest fumble, the quietest giggle, and we'd have to start all over. Sometimes we wouldn't leave until 10 or 11 or midnight.

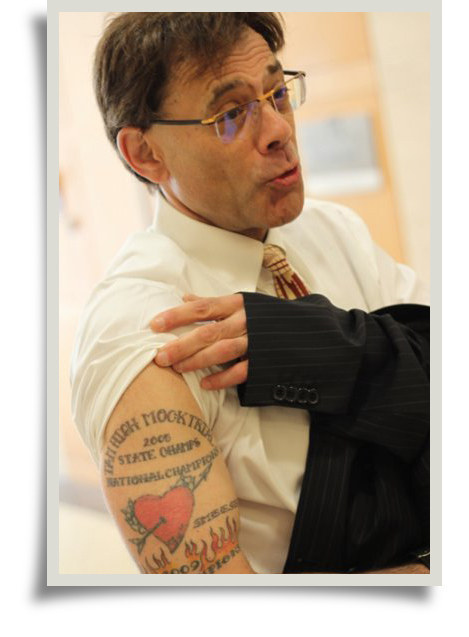

David had a tattoo of a peace sign and another with a heart and his wife's name. He joked that if we ever won state he'd get one that said that, too.

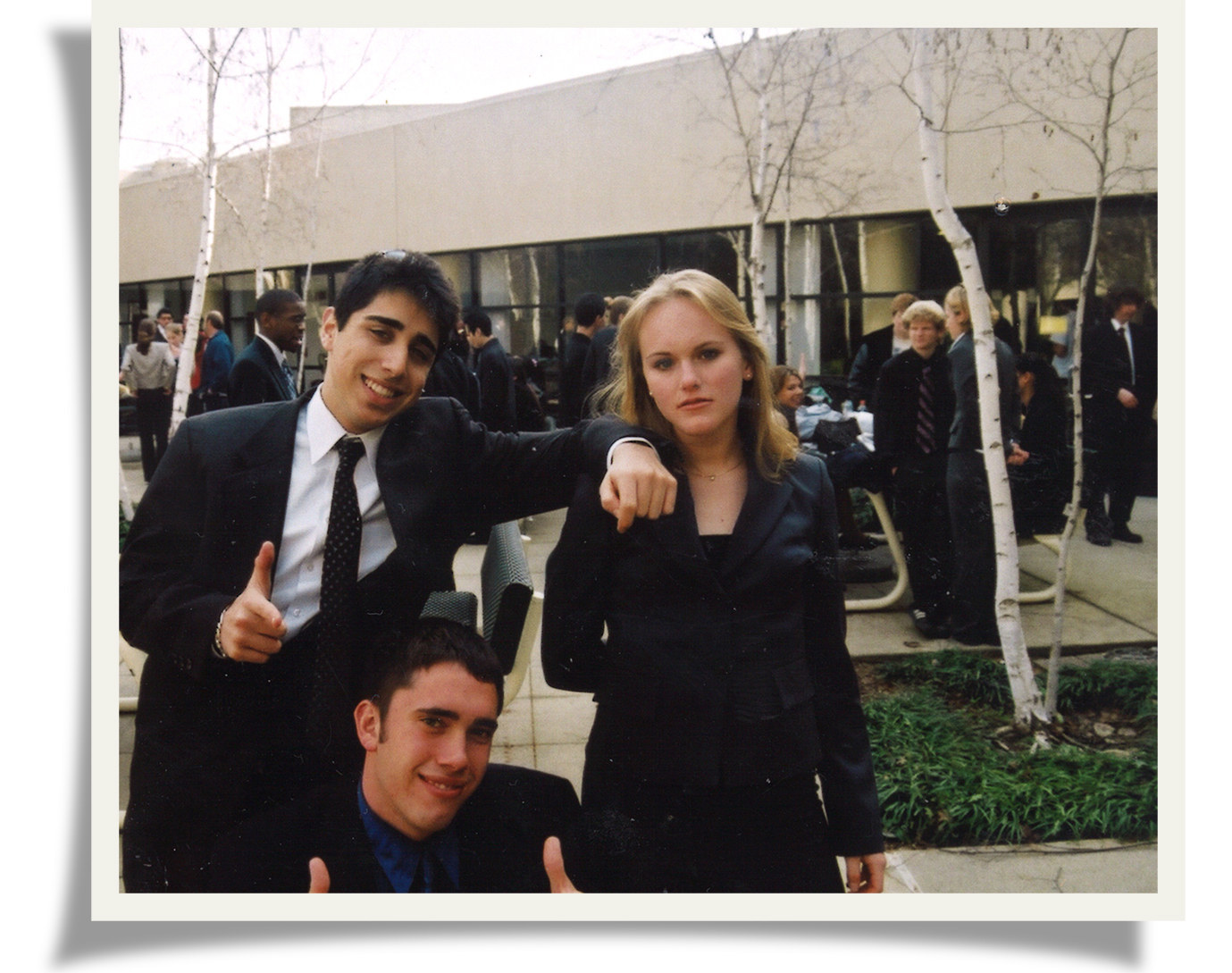

Mock trialers rise before dawn. They plug in hotel irons. They unravel nylons up their legs. The younger guys on our team would congregate in older guys' rooms to have shoes polished and tie ties. Mothers would set up in others to flat-iron and braid hair. Our senior year, at the state competition, my co-captain, Max, brought a bag of good ground coffee for the two of us, so we didn't have to suffer the free stuff, and I'd knock on his door for a cup. David would be outside long before our team got down, yelling notes he wanted to give various members of our team into his voicemail.

Mock trialers click-clack down pedestrian malls and city streets toward the courthouses where they compete. My teammates and I became accustomed to bystanders not knowing what to make of us. I’ve never worn a suit more frequently, nor better, than when I was 17.

Something I do not know how to do, I realize the morning of the first 2015 national competition, is dress to spectate mock trial. Hence it is 7:36 and I was supposed to be at the Wake County Courthouse at 7:30, and I’m pulling a dress I’ve now put on twice back off of my body. How many hours of mock trial I sat through and I cannot remember how dressed up those in the gallery were.

Maybe that's why I'm having something of a meltdown in this Raleigh Holiday Inn. Or maybe it’s that it feels right to wear a suit to court and it also feels wrong to wear a suit to court. I’ve made a big cup of coffee that reveals itself to be basically scalding water. Tongue burned, I put the dress back on. And pull the blazer from my suit, which hangs in the closet, taunting me. I put on flats but throw heels into my bag.

I scamper across the dead downtown and I’m not that late by the time I get through the metal detectors and find the right floor and courtroom. I meet two of California’s attorney coaches. Neither seem as stressed out as David would be on competition days; he often didn't actually watch the rounds. I whisper to one of Redland's coaches that I used to do mock trial myself, that I'm from California too and was on Marin County's team. He replies, "That's the coach that walks the halls, right?" I notice that he is clutching something, and as the trial gets underway, discern that it’s a little stress ball in the shape of a fish.

Here’s how mock trial works: All of the teams in a given competition prepare to present both sides of a given fictitious, though sometimes goofily "ripped from the headlines," court case. In addition to attorney and witness roles, there are auxiliary ones like timekeepers — unlike real trials, mock trials are very tightly timed — and a bailiff, who swears in witnesses. During a given round of competition, one team’s defense will go against another team’s prosecution (or plaintiff, if the case is civil). The teams then pretend to have a legal proceeding against each other, which is presided over by a judge — usually a real judge, robes and all, gladly volunteering his (or occasionally her) time. Three scorers, often attorneys who are also gladly volunteering, sit in a jury box and score students on each individual performance. Mock trial is therefore subjective, like ice-skating, or gymnastics.

During a round, one side calls its witnesses and gives each a direct examination. A given witness is pretending to be somebody and when they’re cross-examined by an attorney for the opposing team, they have to answer questions in a manner that’s totally faithful to their character’s witness statement — else they risk impeachment. As they answer, they are nonetheless trying, however imperceptibly, to trip up the attorney who’s questioning them. And the moment she feels she may, an attorney for the side presenting witnesses will quickly rise and say, “Objection, your honor.”

The first time I hear it this morning, my palms break out in sweat, a dormant response awakened.

The room heats up. The judge looks to the attorney who’s asked the question, who now must respond, cite some law about why something is allowable (“Your honor, I wasn’t asking the witness to speculate, I was asking him what he observed”). The attorney who made the objection then responds — “Your honor, opposing counsel has just conceded that she is asking him to speculate” — and they go back and forth, and depending on how long a particular judge likes to let things go, they can become full-on wars, two sharp minds bolstered by pure passion and sense of purpose equally matched to each other, fighting about imaginary things — in this case, a civil case brought by a man or woman named Andy Archer against a security firm called Blount Force Security.

Most of the cases mock trialers are made to seriously argue involve silly, gender-neutral names (Darian Kendall, Aidan Hobbes, Beck Martin) — we once had a police officer whose name was Officer Kripke (not Krupke), first name Loren. Most involve teens behaving badly. The day a case would be released, we'd race to our teacher coach's room to print and read it.

As a mock trialer, I argued a pretrial motion in a case about cheating that resulted in one student probably murdering another on a cliff and staging it as a rock-climbing accident. I did another about a student who likely committed a bunch of credit card fraud against his peers. I prosecuted a manslaughter case against an illegal street racer whose opponent died. And at 2005 nationals in Charlotte, after the death of a fictional famed NASCAR driver, I helped his brother sue the manufacturer of a bolt in his seat that had been allegedly faulty. Our secret weapon was a football player on our team named Jason, who played the brother. He was big, especially for a mock trialer, and serious, and when the time came, he would cry, very convincingly on the stand.

Even by high school mock trial standards, I am realizing that this year's nationals case is pretty ridiculous. Archer, 19, is a revolutionary war enthusiast whose family played a part in safeguarding the North Carolinian copy of the Bill of Rights during the Civil War and for decades after, until (and this is based on a true story) they were caught attempting to sell it to an undercover FBI agent. Ms. Archer attempted several times to contact the governor about publicly forgiving her family, and when he was unresponsive, decided to approach him at an event at the state Capitol in her full re-enactor's regalia. As she reached for her letter carrier, which was next to her antique weapon, she was tased by a security guard named Kelly Blount. She then fell down a flight of stairs and shattered her leg — and her Olympic dreams.

California has drawn plaintiff this morning and they call their Andy Archer first. Right now, 48 teams from 47 states and territories (North Carolina’s two highest-ranked teams are participating, in order to make it an even number) are in 24 courtrooms, and 24 different Andy Archers are taking the stand. Another 24 proceedings will begin this afternoon, and there will be two more tomorrow, before finally, two teams will make the final. The national competition is a blind round-robin.

It’s bad news for California, therefore, that for this first round, they've drawn what’s clearly a very good opponent. I hear whispers in the gallery that it's the defending national champions, from Washington state. Meanwhile, California's Andy Archer is leaning into the case's absurdity and really hamming up her lost Olympic dreams, wiping away fake tears.

Washington's lead attorney is also blonde but of a different breed than Summer: hair in a tight bun and big glasses, à la Kim Basinger as Vicki Vale in the 1989 Batman. And she handles the fake crying well, pausing a respectful moment before saying, "May I proceed, your honor?"

The beauty in the sport — and I do, quietly, contend that it is a sport, an intellectual one — is how they don’t buckle under all the pressure. How they respond to each tiny, excruciating moment, and remain poised. How they handle a particularly unanticipated line of questioning. How they handle a particularly bad one. How they handle a witness on the other team who’s particularly evasive or puts on some big goofy accent.

Kids have a breathtakingly different style of play. Some attorneys are loud, aggressive, objection-happy. Others, like Summer’s co-counsel, Ebram, are extremely — deceptively — mild-mannered. He stands up and says "Good morning" to a witness so gently that the witness is never going to notice the trap he's allowing himself to be walked into until it's too late.

Summer is somewhat like I was: forceful but never bossy. Extremely in control.

After it's done, the kids shake hands. Teams each give one attorney and one witness from the other side an award — something we didn't do back in my day. It's sweet. The girls slip on flip-flops over their nylons. Underclassmen carry garment bags embroidered with upperclassmen’s initials.

We sit in the pedestrian mall and eat Chipotle in the sun. Their teacher coach, Donna St. George, chides the boys to remove their suit jackets so they don’t get food on them. The kids are quietly despondent. There’s a lot of talk about whether, mathematically, they could have lost that round and still get third place. “I’m positive we won,” another tells me.

Donna has the sort of sturdiness of character and practicality of dress of a lifelong public school educator. She takes me aside and asks me how I think the round went.

“As a journalist or as a former mock trialer?” I ask, unsure whether that’s even something I’m allowed to ask. The latter, she says. I tell her my honest opinion: Washington was a really good team and her kids also did well. Hard to tell. It's part of the madness of the round-robin: It's always hard to tell.

Donna tells me that she has won state and gone to nationals once before, in 1997, and they’d placed 16th. She confides in me that this year, she just wants to do better than that. I ask her what’s changed in the interim decades.

“It’s gotten a lot more competitive," she says. There didn't used to be two days of scrimmaging before the competition even began, for example.

I slip away — maybe because I can, maybe because I can’t actually go back to a place where I am invested in the throes of a high school mock trial competition. I go looking for an iced coffee.

“You, with the whatever it is?” the barista nods at my blazer.

“Oh,” I laugh. “Not really. Sort of. It’s a high school mock trial competition. Nationals.”

“Oh, I get it now,” he says, though I'm not sure if he does. “Earlier there were some of them in here, they looked like attorneys, but I thought, if they were really attorneys they’d be drinking alcohol.”

It was a mock trialer, that same senior who'd told me to audition, who gave me my first drink — Crown Royal in a Crystal Geyser bottle, a sip on a dark, foggy beach beside someone’s smoldering fire. That year, I became his project, his mentee, his something. His friend. He quoted Cruel Intentions. He quoted Swingers. He gunned his white Taurus through foggy suburban streets, heaters on our feet and Beyoncé blasting. He was how I got into my first real party. He asked me to be his date to homecoming and some girl in my history class was impressed. He was there when I bought my first suit, sprawled across a bench at Banana Republic, telling me what didn't work and what did. I fell in love with him in that utterly fucked-up way that only a 15-year-old girl can, up late talking quietly in my basement bedroom on the phone, Clearasil smudged on my landline's keys.

I remember the giddiness I would feel walking up our high school’s steps to practice, taking the door, walking down an empty hallway. Finding the one classroom with people in it. David, set up in the front in a little desk with a stack of legal pads and a liter of Diet Coke. And my friends — friends I had not in spite of the fact that I was smart, but because of it, something I'd never experienced. Friends who were nonetheless not boring, not unfunny. Friends who actually liked me.

Some Sunday nights David would have the attorneys to his house for extra practice. I was the only sophomore there. He’d order unreasonable amounts of takeout. We’d form theories of the case. We’d try out arguments. We’d be honest with one another about our styles, about our approaches. We felt like real attorneys, whatever that was.

David gave it to us straight. He’d say when something sucked. He didn't treat us like kids; there was no time for that. Every once in a long while someone would say something and he'd pause, and his voice would crawl across the ground as he’d proclaim, with big delight, “Oh, that’s really good.”

Our team got third at state that year. The senior I was in love with came out to me shortly before his graduation. I started dating and lost my virginity to his best friend, another mock trialer, instead.

I'm sizing up California's next opponent as they walk into the courtroom and it doesn't bode well. Wrinkled fabrics, messy buns. Some of the boys are clearly wearing the outfit they’d also wear to Easter. “Yessir,” is the first thing out of one of their attorneys mouths — not “Yes, your honor.”

The judge is an older white man who takes a few moments to philosophize before the round begins.

“One of the reasons I do this is it’s nice to see the other side," he says, his accent folksy. "The juveniles I see — well, they’re going somewhere, but they’re not going anywhere good. You all are the hope for America. Y’all think and prepare. There are other people in this world — all they do is react.” It is a speech I heard so many versions of as a teenager, and one I never liked, but I don't know I knew why.

The judge next invites the scorers to introduce themselves and they also say all-too-familiar things about how much they adore volunteering their time to mock trial. "In my 30-plus years of practicing," one lawyer says, "it's the most rewarding thing I've ever done."

California's opponents this round are from the South and really playing that up, which, it becomes clear, this judge likes a lot. Their witnesses are boisterous and their attorneys are making nonsensical objections but the judge doesn’t seem to care. They're also all really loud. The gallery balloons with stress. I can practically hold Donna St. George’s sighs in my hands.

Then, the girl portraying the plaintiff pretends to the limp to the stand. I hear someone in the gallery mutter, “Oh, come on." She's going to be a chatty witness, it becomes immediately clear. She is ad-libbing, trying to waste as much of California's time as she can.

Summer is getting more and more frustrated at her nonresponsive answers and at the lackadaisical judge. This witness is also one of the only black students I will see compete in the competition. Summer and the witness are vying for control, Summer attempting to object and the judge not relenting. The round is coming unhinged.

"Do you respect law enforcement, Ms. Archer?" Summer asks.

"I respect law enforcement if they're doing what's right," she replies.

I remember one time our team drove to the East Bay, to a school in a poorer area, where the students were predominantly black, for a scrimmage. It was embarrassing how much better prepared we were. But then of course we were better prepared, we children of Marin County. We who could devote countless hours to this activity of playacting at lawyering. We whose parents could help fly us to SoCal, or back east, for competition. We who would finish practice and then smoke pot in our Jettas and drive to the beach. If one of us ever got in trouble, it wasn't like we'd actually have to end up going to court.

I realize something that is true of mock trial that is also true of real law: the power of the luck of the draw. The temperament of your judge. The quality of your attorney. How many other cases she has that day. The zip code into which you were born. And your race. For several minutes I’ve stopped listening to the fighting and have been studying a wisp of a white spider making its way across the hair of an old man sitting in front of me.

After hours the round is finally over. The kids give each other awards; they seem authentically cordial. Summer is two for two. Donna St. George later tells me she had to restrain herself when the opposing coach came up to her to say, "Y'all's kids were just precious."

I don’t remember being so nice when I was a teenager, but it’s possible I was. Or it’s possible that at that age, you’re just better at hiding things.

David did get the tattoo, on his bicep: "Tam High Mock Trial 2005 State Champs." I remember when we won state, when I was a senior, we walked around hot Riverside blocks. Those of us who were old enough, wink wink, chewed on cigars. I remember calling that boy I'd once loved, who'd recruited me to do mock trial, who was now in college, and how nonplussed he sounded when I told him we'd won.

We had just two months to prepare an entirely new case for nationals, and in my probably exaggerated memory of it, we practiced every day after school. We also had the attitude that it was enough just to be there. A public school hadn't won the competition in a long time, and here we were.

By the second day of nationals, though, it was clear that the teams we were facing were getting better, much better. That morning at the hotel, my co-captain, Max, and I had scanned the ballroom's buffet but saw only several carafes of decaf. We asked the waiter for some actual coffee and the waiter replied in a North Carolinian drawl, "Coffee is not for children."

That afternoon, before they were to announce who'd made the final round, we set off in search of a Starbucks. David had taught us to not speculate that much about our chances but we couldn't help it. We walked fast and muttered to each other that there was a chance — a chance — that we were still in it. But that was crazy.

The hundreds of us assembled on some steps and finally someone came out to the podium and announced that the two teams that would be heading into a final competition.

"Hawaii." Screams. "And California."

I heard nothing more. My mind went blank. Max and I were ushered up to the front of the mass. I held my hands in front of my face.

Some parent put a sandwich in my hands and told me to eat. We were rushed up to the largest, most crowded courtroom I'd ever seen and outfitted with microphones. I then began the most important trial of my career as a fake attorney.

California's first opponent of Saturday morning is strong — which is good news, in terms of how they’re doing in the competition as a whole. I feel invigorated on their behalf. This is also a judge who’s very clear about what he will and won’t stand for. He says that normally in his courtroom if he sees a cell phone he confiscates it for 30 days. When the first objection is fired, the judge shoots it down, making it clear he’s not going to allow made-up law just because these are teens: “Negligence is not the essence of any defense that I know of,” he says. “Overruled.”

Summer is on. Her cross-examination of the defendant is really masterful. When opposing counsel objects to one of her questions, it’s the judge who says, almost on Summer’s behalf, “Your client opened the door.”

A student whispers to Donna St. George over my shoulder, “Is she going to cry?” and Donna nods. Her kids are doing great. And even the crying goes over pretty well.

After Summer delivers her closing, I hear Donna mutter, “Beautiful.” The round ends, and she wins her third consecutive attorney award from the opposing team.

I ask Summer's co-counsel, Ebram, what they did to do so well, and he reminds me that she's 18 today: “Right before the round she said, 'It’s my birthday, it’s my last day of mock trial, let’s play hard.'”

“That was one of the most fun rounds I’ve ever done,” Ebram says, exuberant, his tie loose.

Summer thanks me when I say it was a great round. I find myself feeling intimidated by her, sort of stunned by how impenetrable her poise seems to be. “It’s nice to play a team that’s very good and very respectful,” she says.

As we walk to the courtroom elevators, one of their attorney coaches confides in me that the kids seem convinced that they’re still going to win, his tone betraying that he doesn't agree. I feel my own hopes for them bruise. But then again, I've always half-wondered whether winning the thing was what punctured it for me.

Outside the behemoth courthouse, a man stops me and asks why so many kids are wearing suits. “It’s some high school competition I think,” I answer. He tries to hand me a pamphlet.

I dial David Vogelstein.

"Sandra." His voice is gravelly, the same. He's at a diner by himself, eating breakfast; I hear him tell a waiter to go find the eggs he ordered, because these are not those eggs. I tell him where I am, in North Carolina, at nationals.

He says he can't believe I'm calling today, that he's meeting his team tonight for their farewell dinner, and announce to them that after 20 years of coaching mock trial, he's finally retiring.

"Holy fuck," I say.

"Yeah!" he says, explaining it's time, and I say I get it. He says the competition has changed; there are so many pre-competition tournaments now. "I haven't seen my wife in 20 years!"

We reminisce and of course we talk about Charlotte, about the final round against Hawaii, and what happened after. I remember that awards banquet during which the announcement came. How I couldn't eat but just pulled apart a bread roll. How I got in trouble because I wasn't dressed up for whatever dance was to follow. I didn't go. Finally the top 10 were announced. Fourth. Third. The runner-up: Hawaii.

We rushed the stage.

"You fell into my arms," David remembers. "You were shaking and crying. You said, 'I can't do this again.'"

"I did?" I don't remember that.

"Yeah," he says. "It was a little shocking, because you were always so strong. It was great to see you so vulnerable, because when you were in your element, Sandra, you were terrifying."

Mock trial was a way to pretend we were adults. For me it was a forum to be as precocious as I wanted, and as smart and as confident. It was a game with rules that I understood, and I mastered them. But of course we were not adults, not at all, and never had I realized it more fully than when we won this ridiculous thing. Maybe that's why the win defeated me. One of my friends on the team shot himself six months later, just as we finished our first semester of college, and so the win always reminds me of his death, too.

"I did it for my coach," I said to the reporters after, and some congressman who called to congratulate me.

"Are you going to be a lawyer?" they all asked. David crammed the words "national champions" into his tattoo. When they won state again, in 2009, he added that, and flames.

Their last judge is great and brisk and a woman. The team is respectful but not a powerhouse — a sign, it seems, that they will not be one of the two names called late this afternoon. There are some clumsy moments on both sides, and when the trial is through the air is heavy with the realization that for some of these kids, these were their last moments ever as mock trialers.

A few months later, I'm summoned and actually serve on a jury. It's a pretty low-stakes civil proceeding and I'm the second alternate, meaning I don't get to participate in the jury's discussions or find out the case's outcome. For me, at least it's six days of real law as pure theater.

And it wasn't as entertaining as mock trial. Nor as speedy. The culture of mock trial competition is one that bans audience members who aren't friends or family of a particular team, a rule in place, I believe, to prevent spying. If the goal of mock trial is, as we were often told, civic education, I say why not let the greater American citizenry see? I bet if the National High School Mock Trial Competition were televised it'd be watched like the spelling bee.

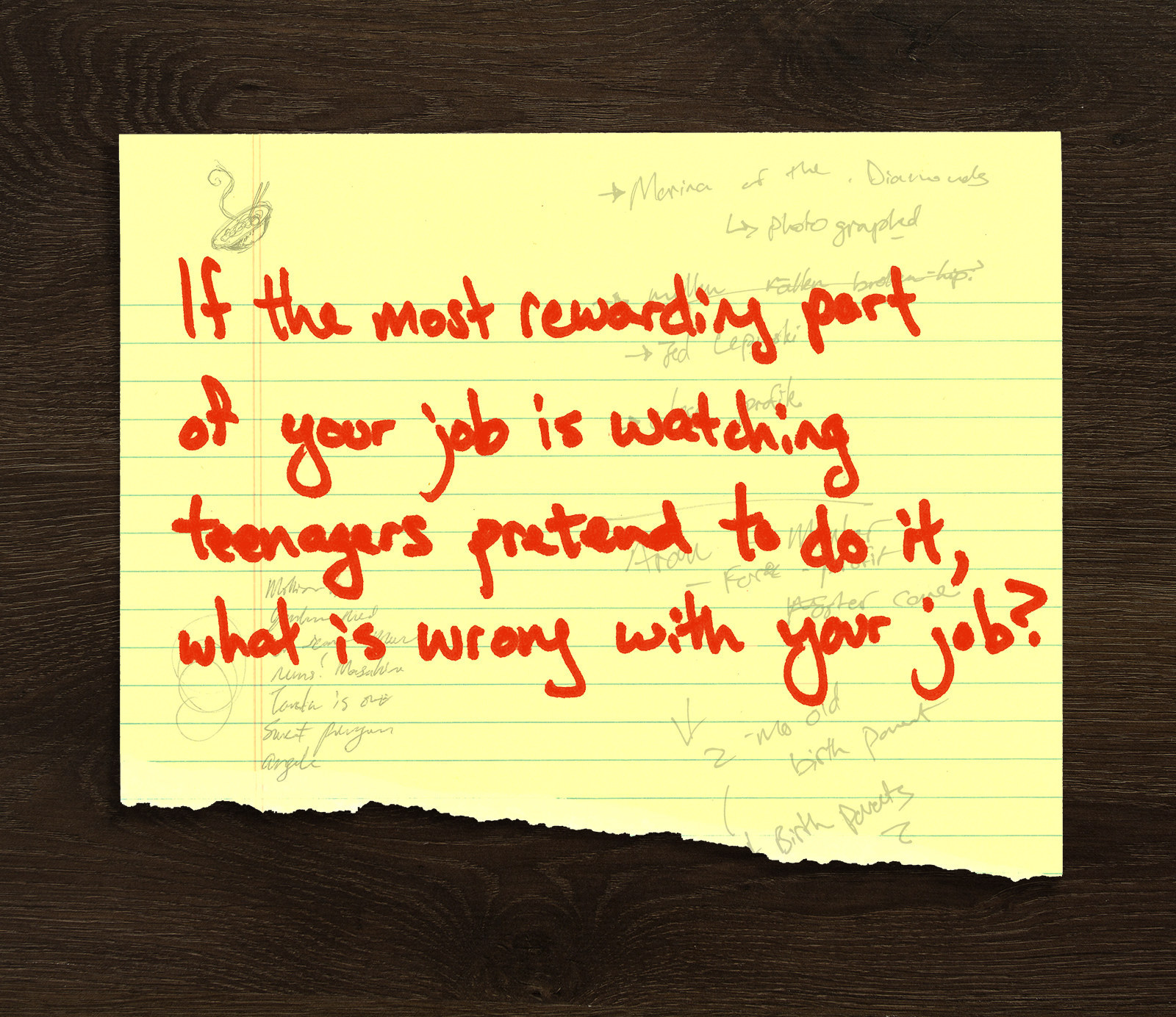

But I'm not sure that's what it's for. Mock trial is kabuki. And it's performed primarily for the legal professionals who volunteer their time to it. The activity is, I think, as much a projection of what those people wish their jobs were as anything else. Real judges, real attorneys — many of whom are good people, many of whom do jobs I could not handle — but who are part of a system that we cannot continue to pretend serves us all. If the most rewarding part of your job is watching teenagers pretend to do it, what is wrong with your job?

Those same empty, patriotic statements about how we have the finest legal system in all the world, ones I heard so many times as a mock trialer, were repeated to me in the VHS tape played to us before jury duty. We were thanked for serving, and doing our part "in guaranteeing the right to a fair trial for everyone across the country."

The mock trialers are tired. They trudge down the pedestrian mall, past a very well-amplified country music concert and a long line for frozen lemonades. They gather on the steps of the North Carolina State Capitol. It's sweltering. Bugs scream in the trees. The mock trialers nonetheless carry their suit jackets carefully just in case they are one of the two teams called for the final. But of course it's unlikely.

Nearby a bride and her bridesmaids are arranging themselves in variously thrilled positions for a man with a camera, while a line of men in tuxedos drink Coors Light from cans on a bench.

Someone points out a team they'd scrimmaged to Summer and says, "There's Illinois. Want to go to say hi to them?"

"I've done a lot of talking today," she says, quietly.

Soon there are hundreds of teenagers in suits occupying every bit of lawn, everyone jockeying for a view, but no one official-looking is yet in sight. A group of boys begins a boisterous, ill-remembered rendition of "Bohemian Rhapsody." California's team sings Summer happy birthday and she blushes. A kid with a nosebleed circles around looking for some way to handle it.

One kid has stood up on a bench. "Everybody wave for Snapchat!" he yells and simultaneously the hundreds of them cheer.

Someone finally comes out, takes a mic, and thanks the teams for being there. The two going to the finals are: "Georgia and…Nebraska." Loud disappointment, and two clumps of screams.

California doesn't look that defeated. They give each other lots of hugs. They console one another with the thought that they might still get top 10.

I go to watch the final and am surprised at how few people are there. Before it begins, I realize I'm in the bathroom with what seems to be the entire team from Georgia, an Amazonian gaggle in butt-hugging dress pants and matching scarlet shirts. They seem awfully calm. "Hey, you guys," one girl yells to the others, drumming up their spirits before their third trial of the day. "I know we always complain about how long we've done mock, but this is why we do mock."

Do mock.

I'd never heard it referred to as just that and I don't like it at all.

The style of play is also not the kind I like — fast, loud, objection-eager. I make it through about the first hour before I slip out. I haven't eaten all day. I go back to my hotel room and eat ribs in bed and find Legally Blonde on TV and fall asleep to it. I forget for a second time about the dance and by the time I wake up it's too late. I learn on Twitter that California didn't make the top 10. They ultimately placed 25th.

Canyon Frost, though, did get an overall award for his performance as a witness, one of 10 students who did. He was very surprised, he tells me later on the phone. "Even though we all felt that Summer and Ebby should have gotten an award too."

He speaks fondly of their team really getting the dance floor going after, and that some of his classmates back at school actually congratulated him when they returned. "I wasn't sure most of my classmates knew what mock trial was."

He and Summer independently use the word "bittersweet" to describe the end of their mock trial careers. ("I didn't realize I'd done my last trial until we were on the plane home," she says.)

I talk with each of them about why they don't want to become lawyers. Summer answers that she's spent a few summers now working in a law office. In mock trial, "witnesses are acting. Lawyers are acting," she says, but in real law, "the victims are real."

I ask her about how she thinks she'll think of mock trial, and the victory she had — captaining the team that won California — in 10 years, or 20. "Years from now, it wouldn't be 'We did so well, won state,'" she says. This is how she'll remember it: "In high school, I got to go to North Carolina, with a group of great people."

There is one image I return to when I think about the nationals in Charlotte. It was late one night, perhaps after our win, perhaps the night before it. My co-captain, Max, and my friend who would soon be dead and a few others of us seniors snuck out to the roof of a parking garage adjacent to our hotel. We lay on our backs and looked at the light-polluted sky and smoked cigarettes. What we talked about I don't remember. Perhaps we talked about our impending adulthoods. All I remember is everything in the world felt enormous and also very small.

Canyon tells me he hopes his teammates go back next year and take it all.

"What did it feel like," he asks, "to be best in the world?"