My first pies were blackberry. In August they’d ripen in the marsh below our house. We’d wear rubber boots and dirty jeans and take buckets, spend hours avoiding thorns, picking. Our cattle dog learned to carefully eat them from the vine, and his gray mouth would be stained purple as he trotted home. My mom would flour a cutting board.

She made the dough with Crisco she kept in a cupboard; this was one of the few things she cooked. The crusts came out mushy. The berries were exceptionally tart. They were perfect to me, my mom’s blackberry pies. I’d tell people they were my favorite food. My first tattoo, a sleeve on my upper left arm, is a tangle of California wildflowers: poppies and lupines and blackberries.

The kitchen was my dad’s domain usually and if he was stomping around in there, it was wise you find somewhere else to be. I hid downstairs. Through the ceiling, stomps became his screams, then hers. The house was in the country, and cold, and quiet except sometimes at night when it got really loud. Every day was either calm or bad and if the latter you didn’t know how bad it might get. I’d listen and hope I wasn’t summoned.

Some years before, we’d discovered a feral apple tree on a lot nearby, a rarity in Northern California. In September, we’d put on long sleeves and tromp through poison oak to pick from it. Home, my mom would again flour a board. Her apple pies were my second-favorite food, I’d tell people. Sometimes she’d bake a pumpkin or pecan pie during the rash of holidays we celebrated toward the end of the year — Thanksgiving, Christmas.

I don’t remember how the baton was passed but by the time I was 9 or 10 years old, I baked the holiday pies instead. Maybe because I quite liked cooking. On the appointed morning, I’d wake up early. The house would be quiet and only mine and the dog’s. I’d warm the kitchen with my oven. I’d carefully measure shortening, cut it into flour with two knives, as I’d seen her do. Over the years I woke up earlier and earlier. I’d bake two then three or even four pies. We’d carefully set them in newspaper-lined baskets and drive an hour to relatives in the East Bay.

In my family, any day could be a bad one but days like this — when you had to dress up and be in the car together — were invariably rotten. At least, then, there’d be the moment, after dinner, when people would finally taste my pies. They’d shriek, “You made the crust yourself? How old are you?”

I had one friend down the street and on weekends I’d go to her place and we’d bake — cookies and cakes. Never pie though. Pie was something I made only on special occasions and alone. Maybe because pie seems personal, intimate. It’s you and the dough. Your fingers and the fat you’ve cut into the flour, the ice water you’ve tossed in to bring the dough together into a ball. That’s step one.

Step two is roll the dough out, a task that’s simultaneously simple and very hard. Over the years I learned that if you’ve not set yourself up well when you made your dough, this step may prove impossible. If your fat wasn’t cold enough or it melted, or your dough got too wet, or remained too dry, you’d find you absolutely couldn’t roll out the dough into anything resembling a big circle, let alone transport it to a pie pan. Over the years I learned, as well, that you cannot try to roll out a dough and fail and then try again without things getting even worse. Thud went my dough into the trash.

Step one, for me, was survive that house. I hid. I did homework. I did extra credit. I read about colleges 3,000 miles away. I did homework and extra credit and I beat on myself if I messed up anything, however small. I did stuff after school, tried to stay out late. I tried to make friends, sometimes found other houses to be in. I loved especially the kinds of houses where people treated one another respectfully. And ones that smelled like something baking. Then one day I was 18 and did it; I flew to one of those colleges “back east,” as we Californians say.

Step two I didn’t see coming, but in retrospect it makes sense: Step two was keep myself alive and even okay as I inevitably confronted all the ways I was shaped by what happened before.

I recall on that first cross-country flight feeling like now I could start over. Now I would be happy. Instead for some years I grew worse. I kept this a secret. I walked around with it, a self-loathing so intense I felt like I was rotting from the inside. I retreated into alcohol, into uncaring men.

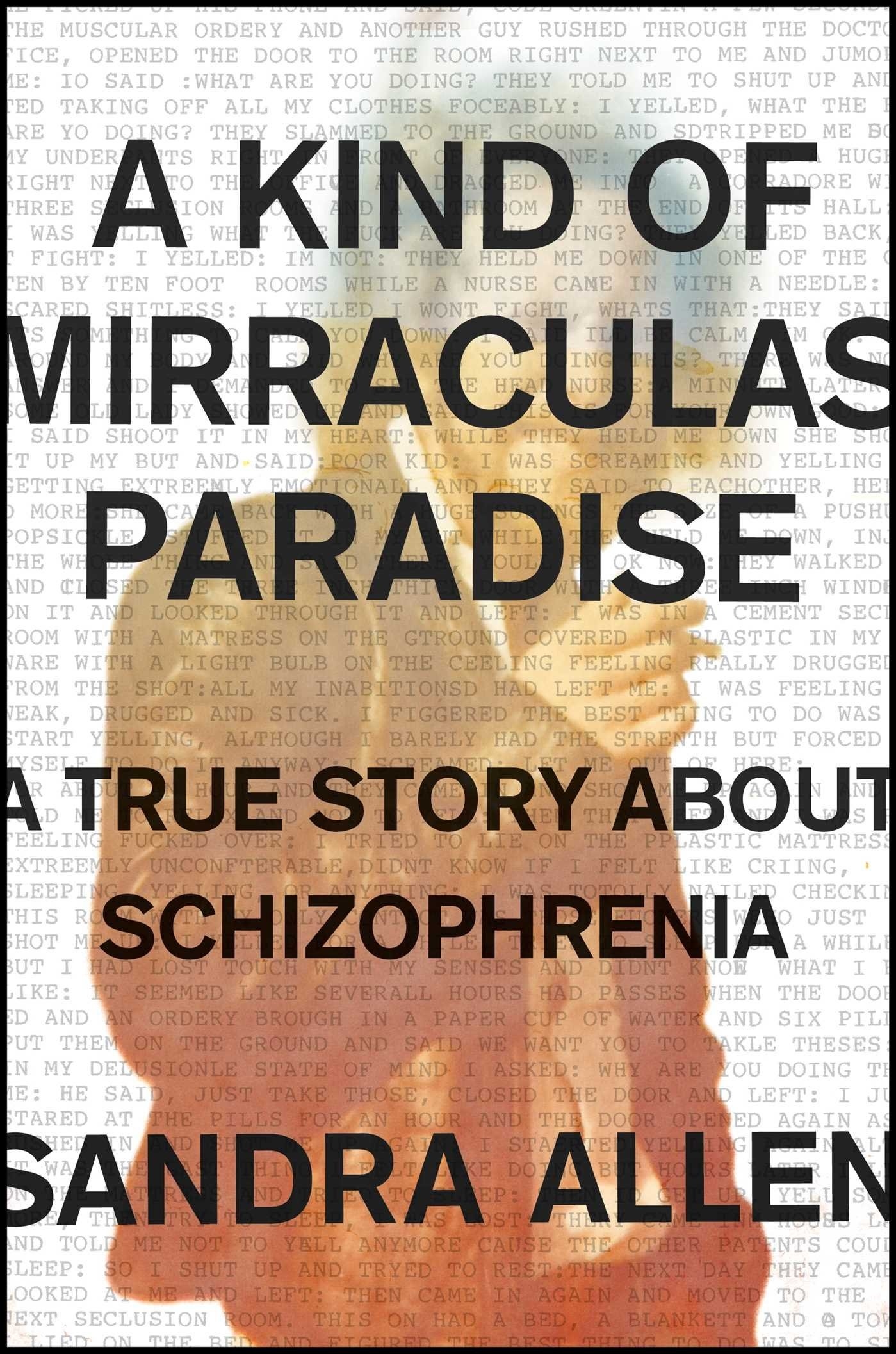

I moved to the Midwest at 22. Soon after I received something in the mail from my mom’s older brother, my Uncle Bob. It was his autobiography, which he’d typed on his typewriter, a stack of about 60 pages composed in all capital letters and punctuated mostly with colons. On a cover page he’d described it as a “true story” about being “labeled a psychotic paranoid schizophrenic.” I began adapting his story into my own piece of writing. It grew eventually into a book published a few weeks ago called A Kind of Mirraculas Paradise: A True Story About Schizophrenia.

Taking care of yourself is an ongoing labor, one that takes commitment.

Through the years I worked on the project, I read a lot about the topic “schizophrenia,” and about “mental illness” or “madness” more generally. I interviewed a lot of people about these topics, people who might have perspective to lend. People, I found, held all kinds of beliefs, and strongly. Much of what I learned was often contradictory. What my uncle had written about his life, for example, conflicted with much of what had been said about him by people who knew him well, and also what the psychiatric profession says about people with his diagnosis.

As I learned, as I encountered such conflicts, I tended to try to listen, to get a sense of where the disagreements were and think about what caused them. In my own book I try less to take sides and more to give the reader a portrait of the debates — making sure, though, that those of us who’ve never been “labeled schizophrenic” really listen to someone who has been, especially on the topic of himself.

During the last few years, since I’ve known this project would be a book, I have asked people who’ve been there, people who have “lived experience,” as it’s sometimes phrased, about their mental health. People have talked about their “symptoms,” their “challenges,” their “recovery.” People have told me about their whole lives and their worst days. They’ve told me about what helped them, and what has made things even worse. They’ve told me which words they embrace and which they hate.

My uncle’s story contained his own truths. Bob did worse when he was confined in cells and stuck with needles and left with huge questions about what was happening to him and why. He did worse when he was bouncing from couch to couch. He did worse when people treated him like trash. Or when his meds made him feel like a “zombie.”

He did better when he had somewhere to sleep that day and the next. He often returned to a psychiatric hospital in the East Bay during his twenties, and would spend some weeks or months there, as he put it, “working on getting well.” He did better when he made a friend, or had a girl, or got to do a job he found engaging. He did better when he was in a band, or going to church, really feeling God, or when he was outside a lot — logging, hiking. There was one good stretch in his twenties when he lived in a commune with hippies and spent his time building rock walls and strolling around naked playing guitar and building pens at a nearby goat farm. He also did well during the last decades of his life, when he lived alone and mostly independent in the desert, a self-described “hermit.”

When I’ve interviewed people, I’ve tended to ask them: What’s helped you the most? Many have discussed their religion, their spirituality. Many have spoken about particular supportive people in their lives: an understanding grandmother, a faithful partner, a sponsor. Some have credited their community, or their support group. Many have spoken about their therapist, and the importance of finding one who’s a good fit. A few have credited a psychiatrist. A few have spoken about how one psychiatric treatment or another made all the difference. Many have described finally quitting one substance or another. Or finally coming out. Or finally extricating yourself from a damaging relationship or group. People have praised the virtues of sleep. Or of letting time pass. People have discussed their roller derby team, their church choir, their cat.

My house, I realized, is a house where pie isn’t for special occasions; pie is for any time.

Through these years, as I’ve read and had these conversations, I’ve tried to stay impartial. But I admit that some trends in what I learned resonated with me personally. Like that trauma and oppression play a part in creating distressing mental and emotional states — like incapacitating sadness or self-loathing. Something else people have said that was certainly true for me: Taking care of yourself is an ongoing labor, one that takes commitment.

I’ve often contemplated my own answer to that question: What’s helped the most? I’ve thought about all the things, big and small, that have made a difference on a given hard day, or month, or year. One answer surely — something I’ve done a lot since I sprang free — is stand alone in a kitchen, with a knife, with a pot of oil, with a floured board.

I cooked for myself and I tried to find others to cook for. Roommates, friends. Boyfriends. Into my twenties I cooked big meals, held dinner parties, wine tastings. I cooked my first Thanksgiving dinner in Iowa, made two pies for four people. The next year I got up earlier, made three.

Year after year, crust after crust, I got better at seeing when I’d erred, pie-wise. I learned how crucial it is that your fat be cold; like many pie bakers, I now refrigerate my dough at least an hour before rolling it out. Like many pie bakers, my life was forever changed when I bought a $10 tool called a pastry blender. Something else I saw too: It doesn’t matter how many pies I’ve made; once in a while, inevitably, I’ll totally fuck one up. Something a lot of people have said when I’ve interviewed them that certainly is true for me: No matter how strong you may feel today, none of us has any clue what’s coming next — in our world, in our heads.

As a kid, I quietly mourned not having one of those mostly smiling families you saw on TV. For the last dozen years I’ve built myself a great and beautiful chosen family, a network with tendrils all over the globe. Some loved ones I see often, some only once in a great while. But at some point, those who need to show up in my kitchen. I set something I’ve made in front of us, and together we take that first bite.

A year ago, my partner and I saw a farmhouse for sale in upstate New York. It had sat on the market a while, full of sheet-draped sofas and rodent shit. We had recently realized neither of us had desk jobs in the city and wondered if we might now move somewhere less expensive, somewhere green. We went there first in February; the yard was an expanse of frozen mud.

It was ours in May. Only then did we realize the backyard had several apple trees, each a burst of white blooms. A man from a local forestry association guessed that of the dozen apples, the largest was perhaps a century old. It was magnificent, stately, its two-toned flowers suggesting it’d bear two sorts of fruit. He pointed at a twiggy sapling on the lawn and exclaimed, “That’s a peach tree!” There were raspberries by the driveway, too. In June, I realized that right out my kitchen window was a thicket of blackberries. I hadn’t realized there were blackberries anywhere on the East Coast.

Never have I made so much pie. Blackberry pie and peach pie and peach and blackberry pie, which I took to calling “yard fruit pie.” In August and September, apple pie. Savory apple pie with lamb and thyme. Most of the apple trees gave no fruit. The old one did — one hemisphere of it gave tons of apples, albeit tiny ones. Peeling them felt like peeling a doll’s fruit. When sliced each section was the size of a garlic clove. The peach tree was the star, her thin arms laden with fruit the size of tangerines, and as sweet.

I made pie and I made pie. I stopped looking at recipes altogether, began assembling dough with ease, and throwing fruit and sugar and lemon juice into a bowl sort of instinctively. I could now feel when a dough was coming together exactly right. My house, I realized, is a house where pie isn’t for special occasions; pie is for any time.

I made pie for the friends who came. I made pie for new neighbors. But really I made pie for myself. I was drowning in fear, fear about the book especially, fear about people actually reading it, about what they might say. Some mornings I’d wake up already deep in some long conversation with some rude interlocutor about all the ways in which it might all go wrong and how it’s all my fault.

I’d trudge down to the kitchen. I’d get down a cutting board, the jar of flour. I’d think of something to bake. I’d try to focus on that for a while.

Yard Fruit Pie

(Adapted from an old Smitten Kitchen recipe; she now champions butter-only crust. I include a little Crisco because nostalgia and I think it gives the dough some forgiveness.)

2 ½ cups all-purpose flour

1 teaspoon salt

1 ½ sticks butter (cold as possible), cut small

½ stick Crisco (cold as possible), cut small

½ cup ice water

A pie’s worth of fruit (5–6ish cups); works well with a combination of stone fruit and berries (store bought is of course fine)

Couple tablespoons of lemon juice

A cup or so of sugar

Some flour (1-2 tablespoons) to thicken

2 tablespoons butter, cut small

Measure the flour into a bowl, and mix in the salt. Cut cold fat into the flour using either two (cold) knives or a pastry blender. Add ice water a little at a time to bring the dough together (can use a fork). Shape it into two balls of roughly equal size and then flatten the balls into discs. Wrap with plastic wrap and refrigerate for at least an hour (and up to a day). (If you want to use the dough later than that, freeze it instead.)

Preheat oven to 375°F. Flour a cutting board. Flour your hands and your rolling pin (can use a wine bottle if you don’t have one). Roll out the disc into a circle a bit bigger than your pie pan. Roll from the center out. Don’t let it stick to the board. Flip it over once or twice as you roll to ensure it’s not sticking. Add a little flour as needed. Once it’s large enough, carefully transport it to your pie pan, either by folding it in quarters or rolling it on your pin.

Prepare your fruit and toss with lemon juice and roughly a cup of sugar (depending on how sweet your fruit is and how sweet you like your pie). I sometimes add a couple dashes of nutmeg or another spice, depending on my fruit and my mood. Add the flour to the fruit, and add the fruit to the pie pan. Top with the last 2 tablespoons of butter. Roll out the second half of the dough and put on top. Crimp the edges as you like (a fork is easy, as is pinching). Cut some slits in the top to let steam escape.

Let bake for 25 minutes and reduce oven to 325°F. Bake for another 20 minutes roughly, until the inside is bubbling and it’s browned on top. You can cut strips of tinfoil to protect crust if it’s getting too brown while baking.

Let cool enough so the fruit can set and you won’t scald your tongue. Eat pie. ●

Sandra Allen is the author of A Kind of Mirraculas Paradise: A True Story About Schizophrenia (Scribner) and a former BuzzFeed features editor. More at www.sandraeallen.com.

For more information on A Kind of Mirraculas Paradise: A True Story About Schizophrenia click here.