People on WeChat, the Chinese messaging app, are evading censors by translating a viral interview from a Wuhan, China, coronavirus whistleblower by rewriting it backward, filling it with typos and emojis, sharing it as a PDF, and even translating it into fictional languages like Klingon.

The heavily shared interview from the March edition of the local state-run magazine, People, was with Ai Fen, the director of the emergency department of Wuhan Central Hospital. Ai was the first doctor to pass along information about the then–mystery illness inundating her hospital.

The pictures that Ai took of her patients’ charts made their way to a group of eight doctors who shared the information on WeChat in late December. Wuhan police arrested them in late December on charges of "spreading rumors." One of those doctors, ophthalmologist Li Wenliang, contracted the virus while treating patients and died in February.

Censors keep deletin a story went viral about Ai Fen, a Wuhan doc who took pics of patient’s test results in late Dec and alert ppl. So Chinese netizens found their own ways: sharing in reversed order, as PDF, with intentional misspelling of characters, and in emoji #COVID2019

In the interview, Ai spoke about how her hospital’s disciplinary committee gave her "an unprecedented and severe reprimand" for spreading rumors.

WeChat’s censors — which monitor blacklisted characters and use “optical character recognition” to scan images or screenshots — immediately started blocking messages that included text from the interview. But people soon found a clever way to share it anyway.

As the coronavirus ravaged mainland China, WeChat has become an information battleground. The messaging app, owned by Chinese conglomerate Tencent, has allowed ordinary people to track the virus — as well as pass along hoaxes and misinformation.

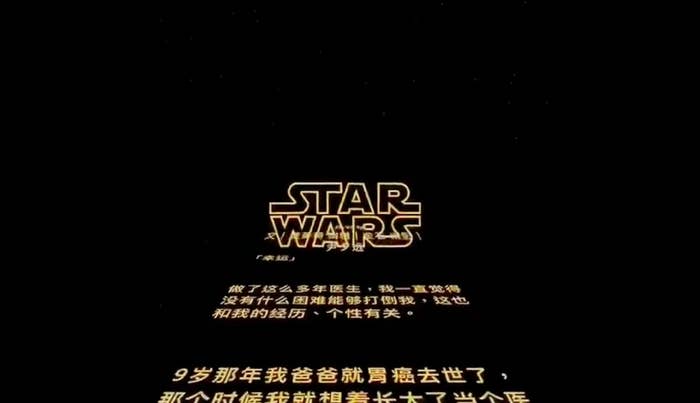

But according to a recent study released by the Citizen Lab, an interdisciplinary research group based at the University of Toronto, WeChat has been aggressively censoring content related to the coronavirus outbreak since at least late December. So to avoid the censorship, people have converted parts of the interview into Morse code, filled it up with emojis, or translated it into fictional languages like Sindarin from The Lord of the Rings or Klingon from Star Trek. In one particularly creative example, someone inserted it into the iconic opening crawl of Star Wars.

吹哨子的人,今天至少出来一百个版了,下面转发电影版,中国人民有智慧。

Wuhan doctor Ai Fen shares her own story of being disciplined for sharing early December 2019 diagnostic reports on the coronavirus -- and web users fight to keep it alive online, even resorting to telegram codes. https://t.co/yLAxVc2Kne

Henry Gao, a Chinese trade law professor living in Singapore who was sharing WeChat screenshots of the Ai interview on Twitter on Tuesday, told BuzzFeed News that in the beginning of January, his friends and family still in China were very careful about mentioning blacklisted topics — but now, not so much.

“I had a few friends who were blacklisted on WeChat for a few days because they said something about the cover-up,” he said. “But when they came back, they kept it up.”

He’s been shocked at how viral WeChat content about the eight Wuhan doctors wasn't being swept under the rug.

“This means we're seeing something like a tipping point,” he said. “In the past when things are censored, people forget about it.”

but hey, who can forget about millennial and emojis?

Users resort to the so-called martian lang, blockchain, orcale bone script, morse code, braille, even mao's calligraphy to spread the article. Many call this a "mass performance art."

Renee Xia, the international director for Chinese Human Rights Defenders, told BuzzFeed News she’s seen an increase in everyday WeChat users acting more brazenly about censorship following the COVID-19 outbreak and outrage over Li’s death last month.

“It used to be that some cyber activists would use these tactics, but now all kinds of online users have used them,” Xia said. “A much broader and deeper distrust of the government has spread in the country since this public health crisis began in January.”

Xia said that while the coronavirus outbreak and its political ramifications in China are still very fluid, she believed it would have profound effects on President Xi Jinping’s administration.

“We're yet to see more clearly what will come out of it,” she said. “This unprecedented danger to public health in China does present an unprecedented opportunity for change since Xi took power.”