Refugee families in Europe today share a common story: displaced from their country in fear for their lives, driven to flee to the West, and facing a gruelling challenge of setting up a new life in a foreign country – but still longing for their old one, mourning what they’ve been forced to leave behind.

If you strip away the international media coverage given to the Yousafzai family over recent years, their story is the same. Except the attention was to be expected: At the centre of their escape from Pakistan is an extraordinary young woman, Malala, whose tale of survival – being shot in the head by the Taliban while she sat on a school bus – has been etched into history, and has led her to become the world’s most vocal champion for girls’ education.

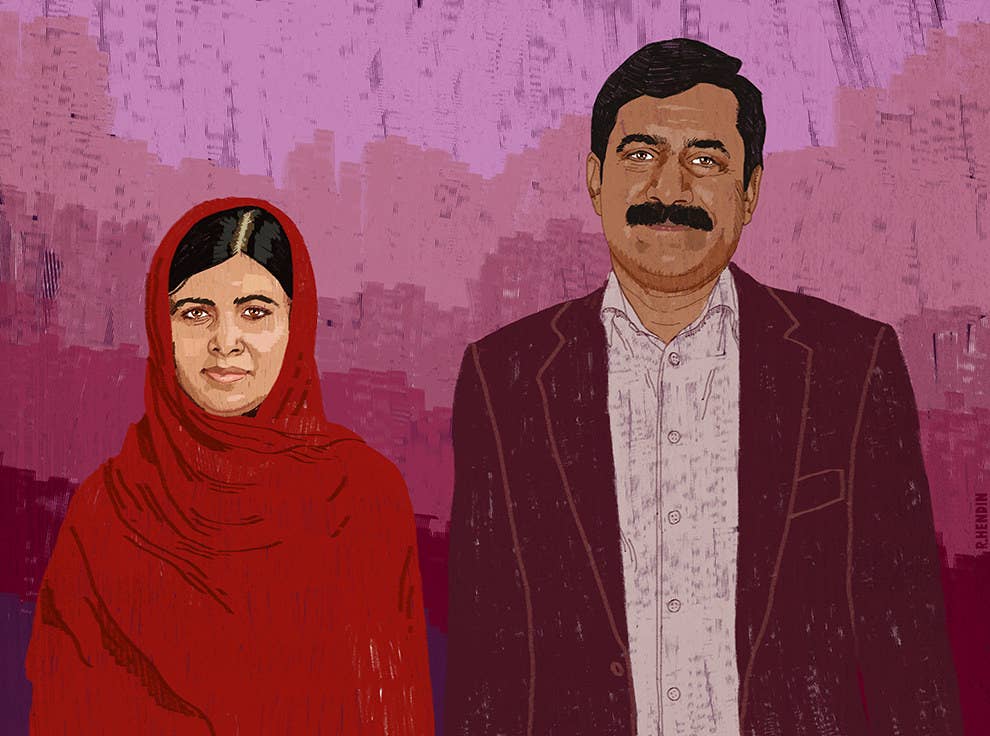

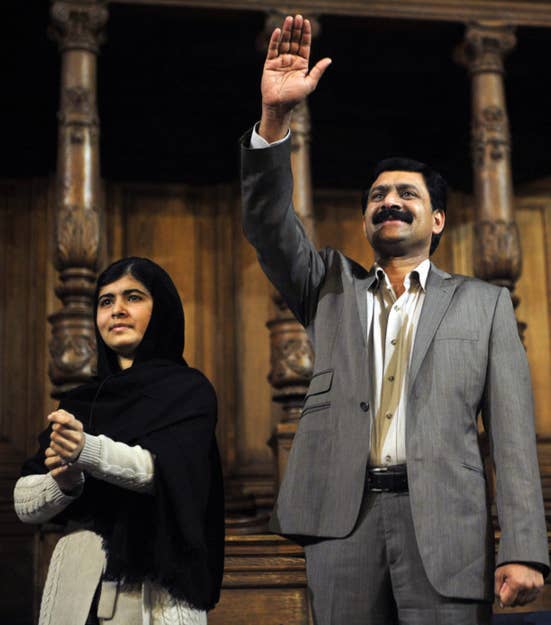

Malala’s father, Ziauddin Yousafzai, understands that their experience resonates with the thousands of refugees who continue to cross into Europe in 2016 in search of safety, knowing that most would face certain danger or death if they were to return home. He says he and his family miss Pakistan, but have adjusted to their new life in Birmingham, in England's West Midlands, where he lives with Malala, his two sons, and Tor Pekai, Malala's mother.

"This second life in England is not just Malala's, but mine too,” Ziauddin tells BuzzFeed News. “They wanted to kill me too, I was on the Taliban list. Who is killed first, who is killed second? Targeted killings happen every week. Now, this is a new life for us.”

Ziauddin has watched on from England as political unrest and a humanitarian crisis unfold across the Middle East and Europe. He reminisces about a similar time he lived through as a child, drawing a comparison between the current refugee crisis – which has left at least 4 million Syrians displaced – and the Soviet–Afghan War, in which millions of Afghans fled the country, many of them to Pakistan.

“I think we have seen this problem in history," he says. "We have had a generation lost because when the war started in 1979 and millions of Afghans fled into Pakistan, many of the youth were recruited as footmen to fight that war in the name of jihad. The real problem the world leaders did not concentrate on – the problem that was totally ignored – was the education of the children.”

Education, he says, is a crucial component to resolving the refugee crisis long-term, as well as the key to preventing radicalisation. Ziauddin is fearful that what he witnessed in Pakistan’s history is now happening again with Syria.

“The world leaders need to learn from their own past. Millions received no education for 10 to 12 years, and the few who were in camps were given basic education, or they were indoctrinated. Their curriculum was like this: Two plus two Kalashnikov guns equals four Kalashnikovs. For mathematics, they were asked: If there are 20 soldiers and five are killed by a Muslim, how many would be left? These were the questions asked.”

“Now we are facing the music,” he adds. “Now what we are seeing in Afghanistan, what you are seeing in Pakistan, in Syria, they are the children who have been left so astray, with extreme views, and they are killing their own people.”

It’s no mystery why, particularly in light of his daughter’s achievements, education is important to Ziauddin. In Swat Valley, in northwest Pakistan, he was a teacher and political activist, and he describes himself as “idealistic”. After becoming increasingly frustrated with the lack of access to education, and despite protests from his brother who told him it would be a “waste of time”, he set up a school.

“When you want to change things, when you are not comfortable with things in your society or country, you have to do something. My brother came one day and told me to be a commissioner, or police officer. I told him, ‘Look at these children; there is a difference in the things that you believe in, and what I believe in. There are 50-200 children in this school, and if 10 of them are rightly educated, and one becomes a leader, then I have done the right job.'"

Ziauddin’s bond with daughter is clear to any outsider. He says that before Malala was old enough to attend classes at his school, she would come to the classroom door and watch him in awe as he taught other pupils. Later, she would deliver impassioned, televised speeches in Pakistan in the same fashion her father once did as a political activist. As a result, both built a reputation for being outspoken, which ultimately led to their names being added to the Taliban's target list.

Today, Ziauddin watches over Malala as she rotates between delivering speeches to world leaders, collecting awards, and finishing her homework. Still, he says that when he thinks back to the day Malala was attacked, he always has tears in his eyes. He believes he is "indebted" to the whole world for her recovery and their new life, and stresses that this is why he'll continue to advocate for the education of girls.

It is also why he urges the world to "expand its obligation" to focus on the “fundamental human right" of education.

"The Syrian war will be resolved one day, as our war did," he says. "But Pakistan is still suffering for 25 years, and we don’t want to see that happen to Syria. A child who is 5 years old now, in 10 years' time they'll be 15, and if they are educated and skilled, they will go back to their country and rebuild it. But God forbid they get no education: They will be a lost generation, and we won’t be able to see a peaceful Syria in the coming years.”

He Named Me Malala is available to view online, or you can buy it on DVD here.