It had been six days since I last heard from Abdul. He usually responded swiftly to my messages on WhatsApp, but this time, I could tell by the grey double tick next to my messages that my latest ones had been delivered, but not been read. The ticks had not turned blue.

"Did you make it across okay?"

"I'm worried, please message me if you get this."

"Are you alive?"

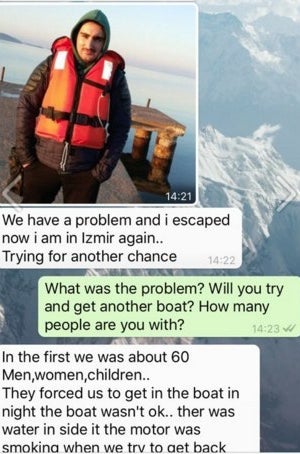

Abdul, a 19-year-old from Syria, had been documenting his journey on WhatsApp for BuzzFeed, and was due to make an attempt to cross the Aegean Sea from Izmir, Turkey, to the Greek shoreline by boat in the first week of November. The crossing is perilous, with rough waters leading to hundreds of deaths, including the case of 3-year-old Aylan Kurdi, whose drowning jolted the world's conscience. Despite the risk, at least 570,000 people have traveled from Turkey to the Greek islands on their way towards Western Europe this year. Even with the arrival of winter and increasingly harsh conditions, the International Organization for Migration told BuzzFeed "record numbers" of people continue to cross.

I went to Abdul's Facebook page. There were no new updates. Had he made it across the sea alive? Had his boat sunk? Was he lying lifeless on a shoreline? Perhaps he dropped his phone in the water. After a long and worrying wait, Abdul eventually replied to my message.

"Hello, I am here. I am shaken, I'm not well."

Abdul hadn't made it across to Greece. His boat, like so many others on that route, had sunk. He swam back to Turkey and survived.

Before it sank, Abdul sent photos of himself waiting to board the boat, as well as a video of himself sitting with other refugees on the small dinghy. Wearing fluorescent orange life jackets, children crouched in the centre and men sat on the sides of the boat. Not seen in the video was a woman traveling with her three daughters from Iraq. Abdul met the family before they boarded in Izmir, where the mother told him they fled after militants threatened to kidnap her daughters. He said she sat on the boat quietly looking over her children.

When the boat sank, the woman's daughters survived, but she drowned.

"She was about 50 years old. I didn't know her name. She said she had to take the journey to keep her daughters safe. And now I can't stop thinking of her face."

"I need energy," Abdul wrote a day later as he snacked on chocolate and drank coffee back on Turkish land, contemplating his next move. When he first reached Izmir, local smugglers shuffled him back and forth across the region by car, driving for hours at a time to squat-like homes where he would sit and wait with other refugees. A video he sent shows him in the back of a car huddled with refugee children and parents, but he quickly moves the camera away when a smuggler's voice is heard.

"I don't know what you call them in English... but they're like the Mafia," Abdul wrote. "They are the men who send us crossing the sea to Greece illegal way. When we first met them, we asked about a boat, and they kept saying in four hours, two hours, tomorrow, counting down for us.

"Then they forced me and many other women, men and children to get on a boat, but we could all see the boat wasn't OK. There was water inside it, and the motor was smoking. But when we tried to get off the boat, they started shouting in Turkish, and then fired their guns in the air. Some people jumped back off and swam back to the beach.

The UN High Commissioner for Refugees has long warned that refugees and migrants will continue to resort to paying smugglers to transport them on unsafe boats, often piling more than 50 or 60 refugees at a time into small dinghies or wooden boats. For this, the smugglers charge at least 1,000 euros per person, turning a human trafficking tragedy into a profitable business. When the weather grew worse and refugees began to doubt whether they should try to cross the Aegean, the UHCR said, smugglers offered discounts for the journey on dinghies that many refugees refer to as the "death boats".

"They don't care if I die," Abdul wrote. "No matter if I die or cross the sea, to them, I equal 1,000 euros."

The journey for refugees traveling to Western Europe has settled into a repetitive pattern: flee poverty or war, risk drowning at sea in unsafe boats, avoid violence and imprisonment while crossing through the interchangeable borders, arrive in a country where a once warm welcome has since been replaced by rising hostility. Refugee after refugee has followed that sequence, and little has been done by EU leaders to protect and support these people, making reports of yet another drowning, or yet another violent clash, all too commonplace and, worse, expected.

Abdul said the route laid out before him and taken by so many others is the only viable option left to escape the violence at home. His once "beautiful" life with his family in Syria changed as the shelling and bombing began. While Abdul was training to become a doctor, Bashar al-Assad's forces imprisoned many of the friends he studied alongside, and as the conflict worsened, he was forced to flee his home country.

"All I cared about was my study, and thinking about my future," Abdul wrote. "I dream of becoming a skillful doctor like my mother. The bombing made studying for that difficult. I was in fear all the time, for my family and myself."

On the day politicians began to declare bans on refugees entering their countries in the wake of the Paris terrorist attacks, Abdul was sitting on that sinking boat in the Aegean watching people around him drown – people fleeing the very same violence inflicted on the Parisians that tragic night. But for Abdul, the risks he has taken to escape that violence were nothing compared to living through it day after day in Syria.

"We couldn't do anything in Syria as civilians," he wrote. "All we could do was watch people around us die and wait for our turn to die."

Abdul's been slower to reply on WhatsApp in recent weeks as he tries to find work so he can afford the journey to his dream country: England. He doesn't know when he'll next try crossing the sea again, but suspects he will need to wait for better weather, and for when he's saved enough to pay the smugglers' fee again. Yesterday, he changed his WhatApp photo to some Arabic text.

"What does your new profile photo say?" I asked.

"Haha, oh that," he replied. "It says: 'you will adore work pressure when you try unemployed boredom'. I have to go now, but I'll talk to you tomorrow."