The Feminist Library doesn’t look like much. Outside there's a hastily scribbled “FEM LIB” above a buzzer; inside, a sign with a dragon guards its entrance.

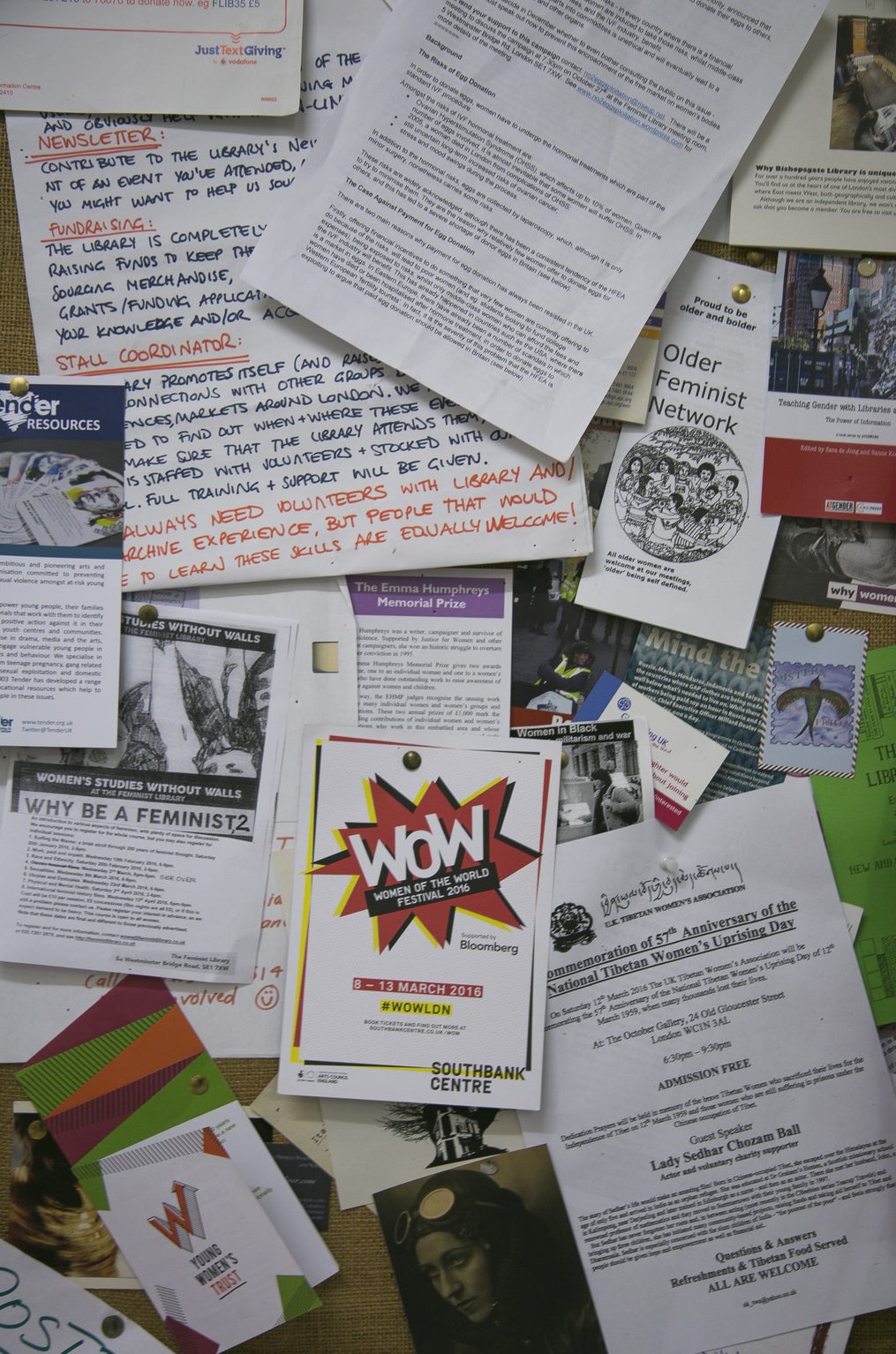

Women sit and stand in an office covered with paraphernalia from the library’s 40 years. They are discussing the order of speakers at the Women of the World festival at the Southbank Centre on 13 March, where they have a stall and an event planned.

Writer-in-residence Caroline Smith is furiously typing at a laptop perched on a packed desk. Over her head fake tombstones inscribed with “Spare Rib” are stacked atop overflowing filing cabinets.

There’s a kind of frenetic energy infusing the three rooms, where the Feminist Library has existed for 30 of its 40 years. And no wonder – just before Christmas the organisation was told by Southwark council it would need to stump up almost £30,000 to remain in its home.

Since 1993 the library has paid minimal fees to exist in the building, but now the council says it needs to pay £18,000-a-year rent and £12,000 in charges by 30 April.

The council says funding cuts from central government means that while it would like to keep the library, it must pay market rates.

In a statement, the council says it has a “responsibility” to ensure its assets are managed responsibly and has offered to help the library find new accommodation.

“It was a sense of disbelief,” Smith says of the council’s decision. “Then outrage: This has been going on for 40 years, this is history, and what – you’re just going to erase it?

"Well, you can’t."

BuzzFeed News spoke to those who work and use the library to discover what it means to them and what lengths they are going to to try and save it.

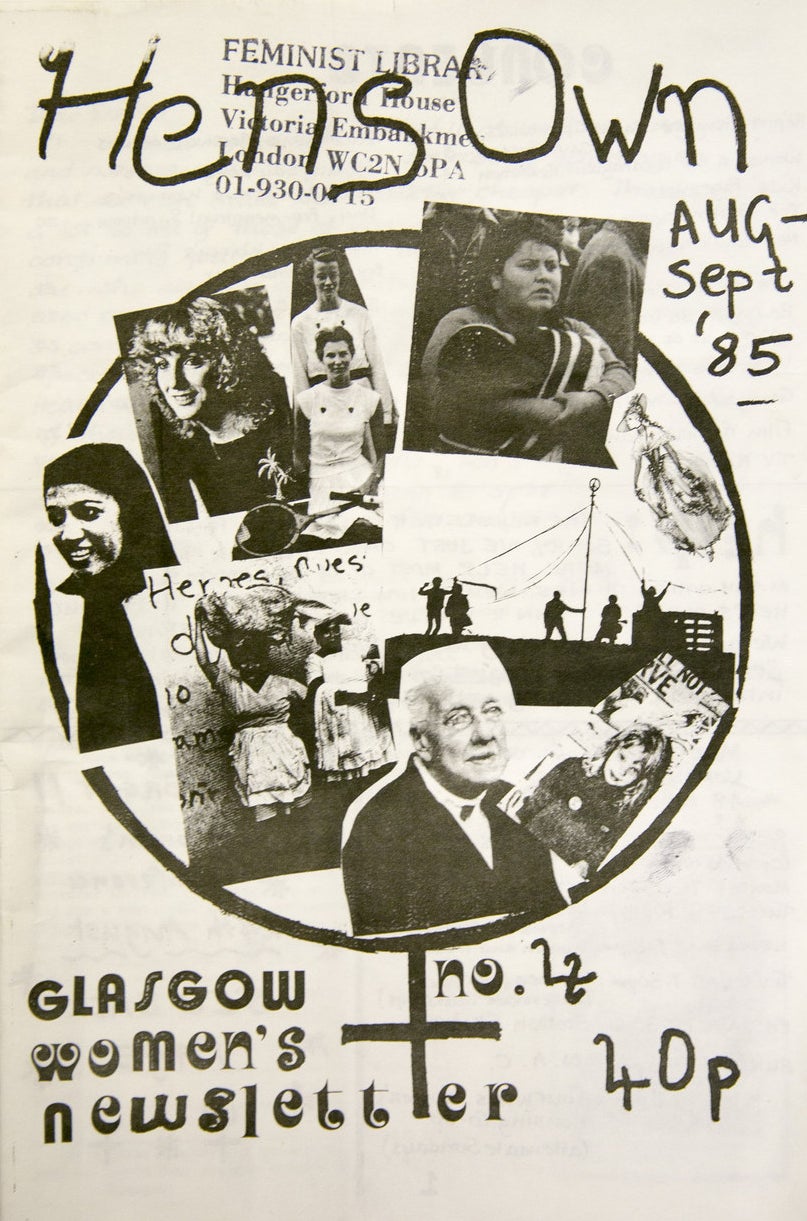

The Feminist Library was founded in 1975 as part of the women’s liberation movement by a collective that included Gail Chester, who is still involved in the library today.

The library, she says, especially in its current location, is particularly important because it provides a link to the local community. “It’s a whole package, it's internationally important, but it is also what it means about creating a women’s community," Chester says.

“On every level, from the cultural, to the political, to the support, it fulfils an incredibly important function.”

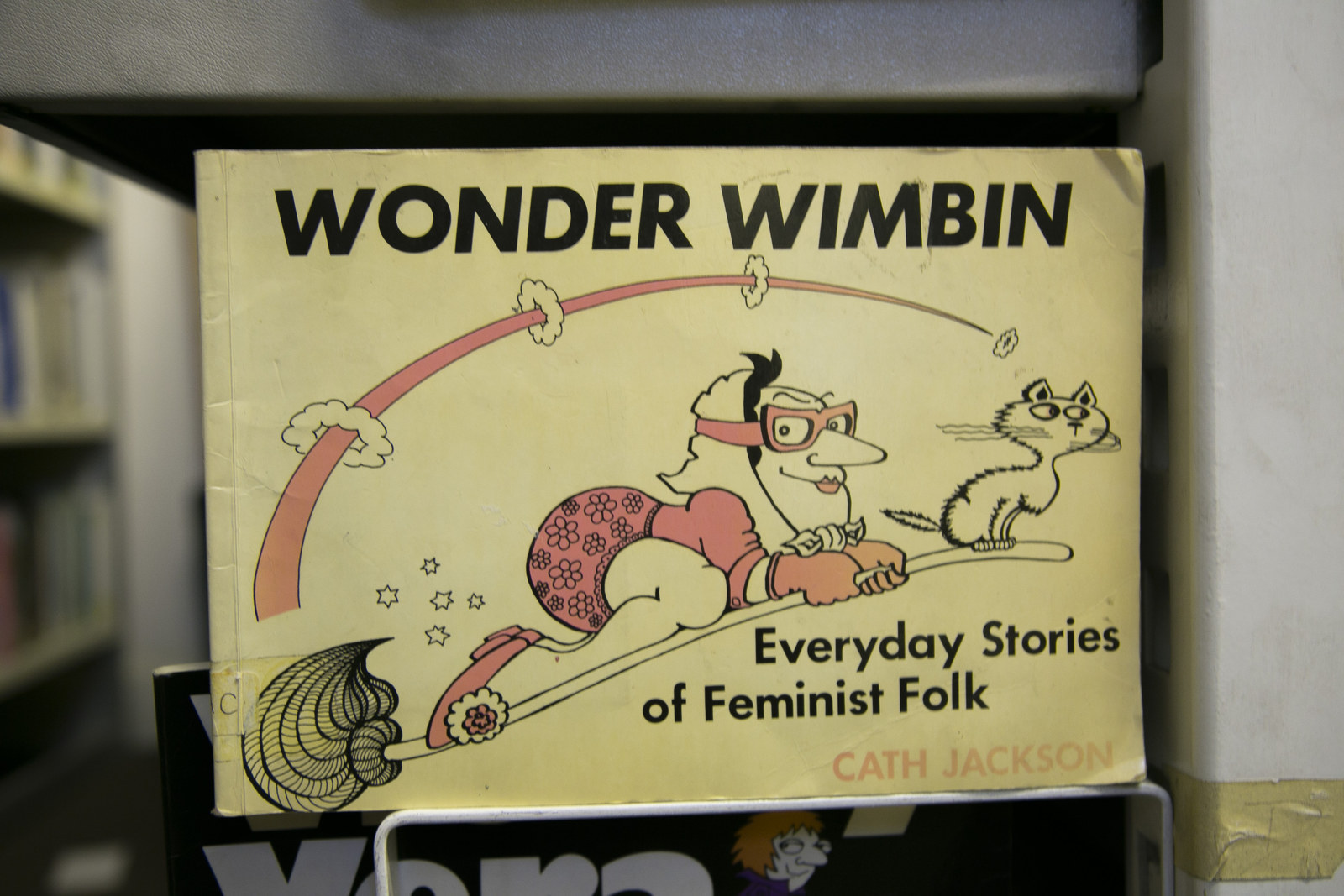

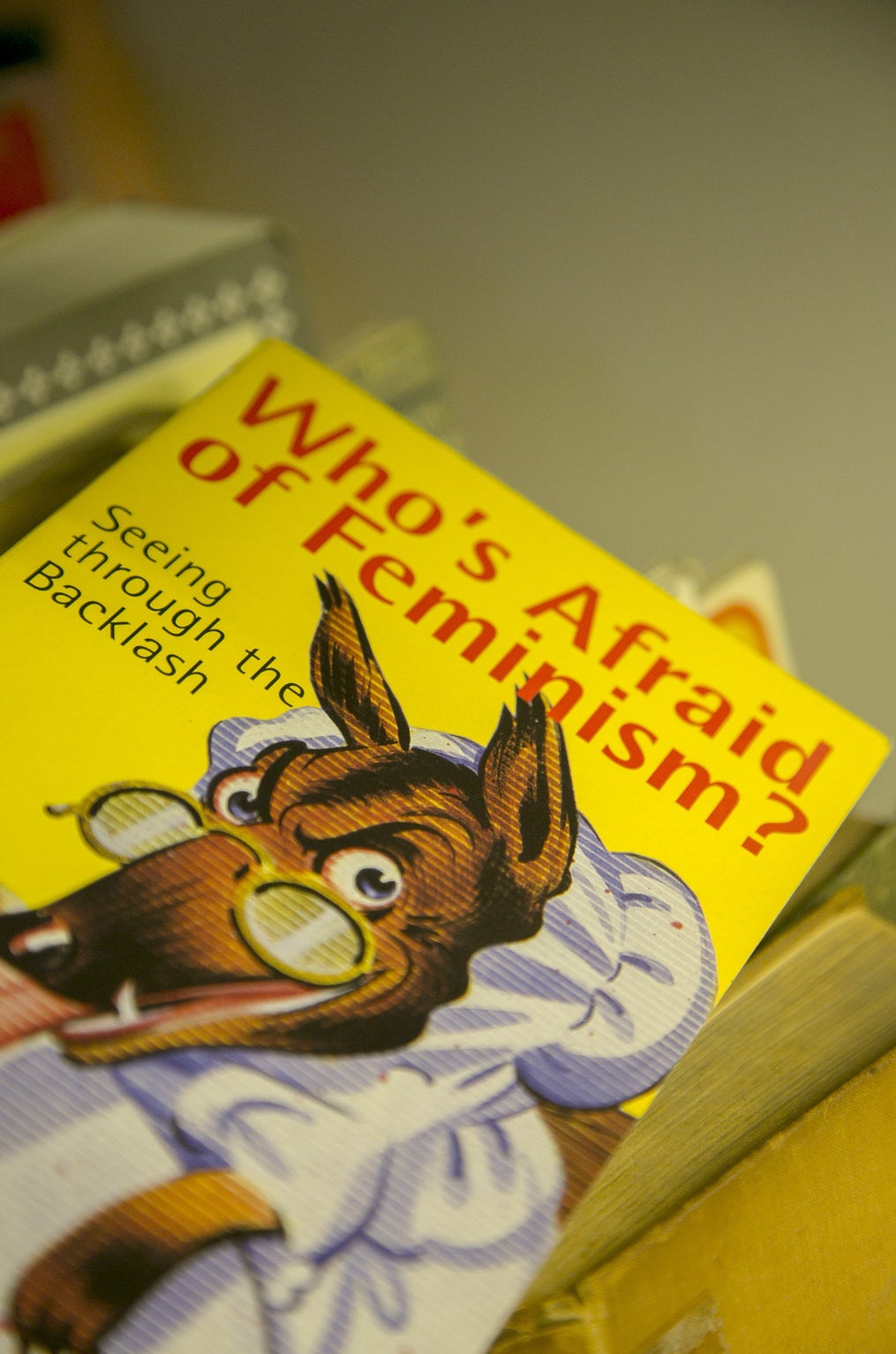

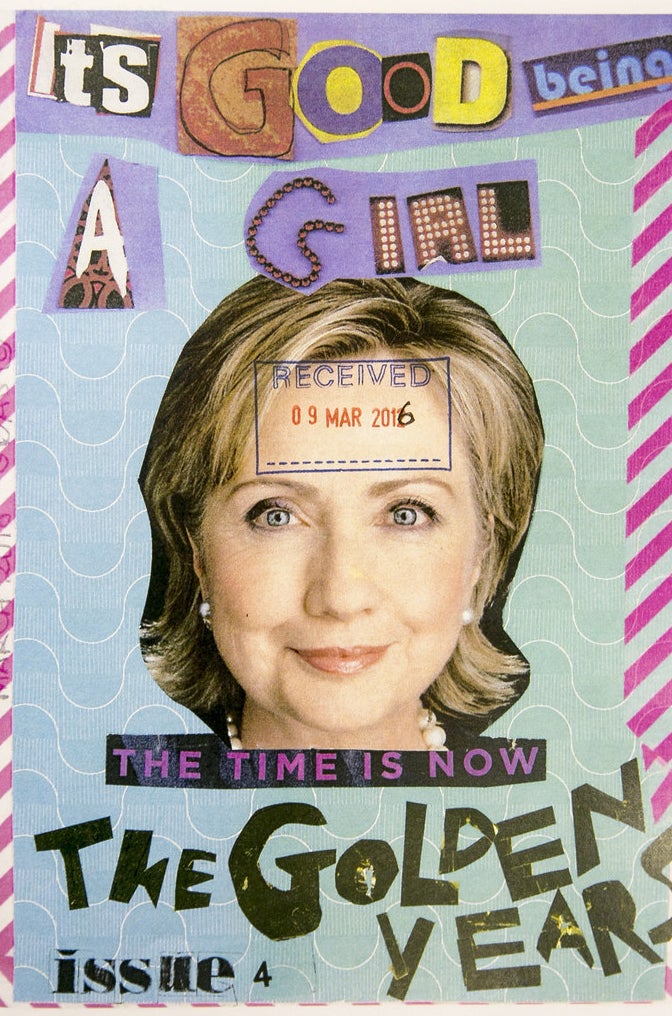

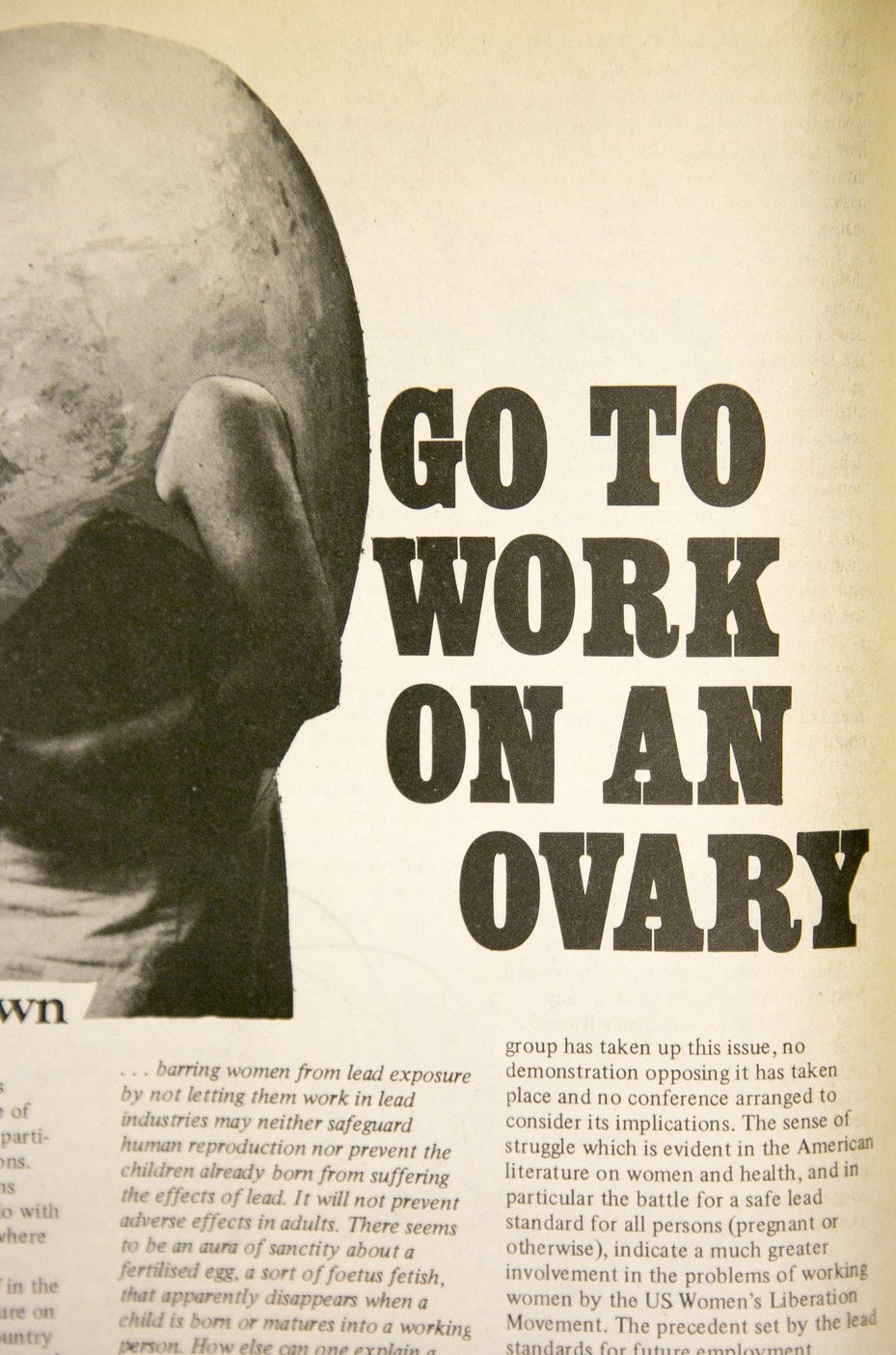

Since the 1970s, the library has expanded to hold more than 7,000 books and 1,500 pamphlets, zines, and leaflets in three ramshackle rooms on the second floor of No. 5 Westminster Bridge Road, central London, just down from Elephant & Castle.

The founding ethos was a push against the regimented. Here, founders decided, would be a place where women’s works could sit side-by-side – irrespective of their cultural standing.

“I would call it untamed – it is truly independent,” says 38-year-old Smith. “I think that alone is a lovely thing to hold on to because I don’t think that happens so much any more.”

Smith, who remembers arriving at the library for the first time dressed as an “eight-foot great frosted cream” for a piece of performance art, says it is the breadth of the library's material available that makes it unlike any other collection.

The library has faced constant threats. After it saw off an eviction in 2003, it limped on until 2008, when a new management team came in, and then received a funding boost in 2010. Now it faces eviction once again.

Currently the library is staffed by between 20 and 25 volunteers who give up their evenings or days. Unlike some other feminist resources, it is open to the public with no booking is required – “none of that nonsense you get at other places,” as 73-year-old Ann Rositer, who is using the library as she writes her book, says.

Rositer, who came over from Ireland aged 18 to have a back-street abortion and got swept up in the women’s liberation movement, has watched the library evolve over the years.

“It’s alive,” she says. “It is very different from what it used to be like, but the ages of women we get in... I listen to younger women and am amazed. The level of technical education is so different from what we had in our day. We never knew such language existed.”

She’s here every week, researching or helping to organise events, be they film screenings, discussions or, more recently, demonstrations to raise awareness of the library’s situation.

Two weeks ago roughly 100 people gathered outside the council’s budget meeting and, in protest at the rent rise, read from their favourite feminist texts.

“Can you believe it? One of the women at the demo had never been on one before,” Chester says with a smile.

Meanwhile, an online petition to save what campaigners and historians call a cultural landmark has gathered more than 15,000 signatures from people around the world, including heavyweight figures like Gloria Steinem and Margaret Atwood.

Although the council says it would like the library to remain, other voluntary organisations in the building have already been forced out. Garweg, a group offering legal advice to disadvantaged individuals, was locked out of its offices along the corridor earlier this year when it couldn’t find the requisite funds.

Smith, who says even that if the library finds suitable new premises the task of moving thousands of books remains, notes sadly: “It’s interesting isn’t it? Which voices fail to get heard or whose voices are fastest to go – and hey presto, we are back at women.”

Sam Smethers, chief executive of the Fawcett Society, a women's rights group with informal links with the library, echoes this concern. “It needs to be that resource for future generations so that they can draw on the past and use it to inform how they take the struggle forward.”

She adds: “I think it is the fact that they [the library] are in this difficult situation is a sign we don’t value that heritage enough.”

Across London, feminists have voiced their concern. Althea Greenan, who heads up the the Women’s Art Library at Goldsmiths, says it is “crucial” London keeps the library.

“There was no overall vision that guides the collection policy,” she says. “It has that loose, inclusive, and slightly rambling remit which makes it very rich and unique.”

There’s no exact record of the number of people who have visited the library, although an old-fashioned visitors book and an assortment of posters on the walls give a hint of the variety of people it has touched.

“I didn’t know such places existed,” says Alice Corble, who first came to the library in 2010, shortly after it won funding from the Heritage Lottery Fund and began pouring money into librarian training for unemployed women – among them Corble.

After previously working in adult social care, the then 32-year-old signed up to take a librarian course after stumbling across the library and ended up volunteering. She is now four years into a PhD at Goldsmiths university examining public libraries.

“I wouldn’t be doing anything that I am doing now without that library,” says Corble. “It really was a catalyst for me, in different ways. It spoke to me as a feminist but it also made me realise I wanted a career in libraries.”

The Feminist Library’s finance officer, Sarah O’Mahoney, 50, agrees. “Even just discovering it, it was like, wow," she says. "I felt like I had found a place with like-minded people.”

Sitting in the library's office as Rositer and Chester gather material together for the evening's activity (a discussion of female sexuality is being held upstairs), O'Mahoney smiles at all the activity.

“It is a woman’s space,” she says. “You have conversations here that you wouldn’t have anywhere else.”