In summer 2015, about a year after Uber launched its Pool ride-sharing service, the company was betting big on it. In order to beat out Lyft and cement its ride-hail supremacy, Uber needed to get droves of riders and drivers into Pool — and fast.

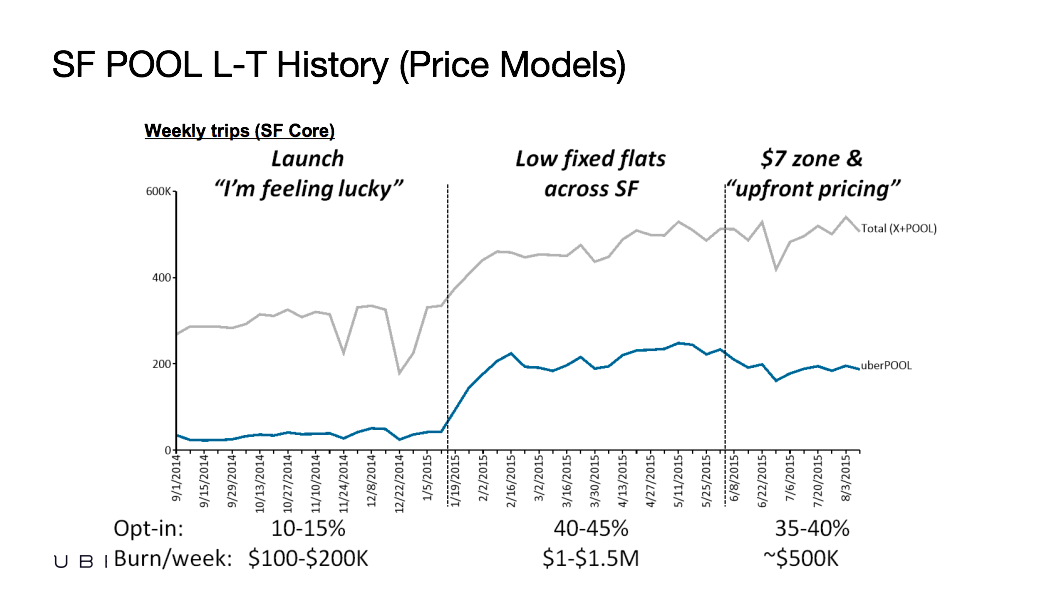

To do that, a trove of internal documents shows, Uber burned vast sums of money to subsidize Pool’s growth — sometimes well over $1 million a week in San Francisco alone.

“We were bleeding cash subsidizing rides and we didn’t have a plan for tomorrow,” a former Uber employee told BuzzFeed News. “Everybody was just trying to put a Band-Aid on this problem.”

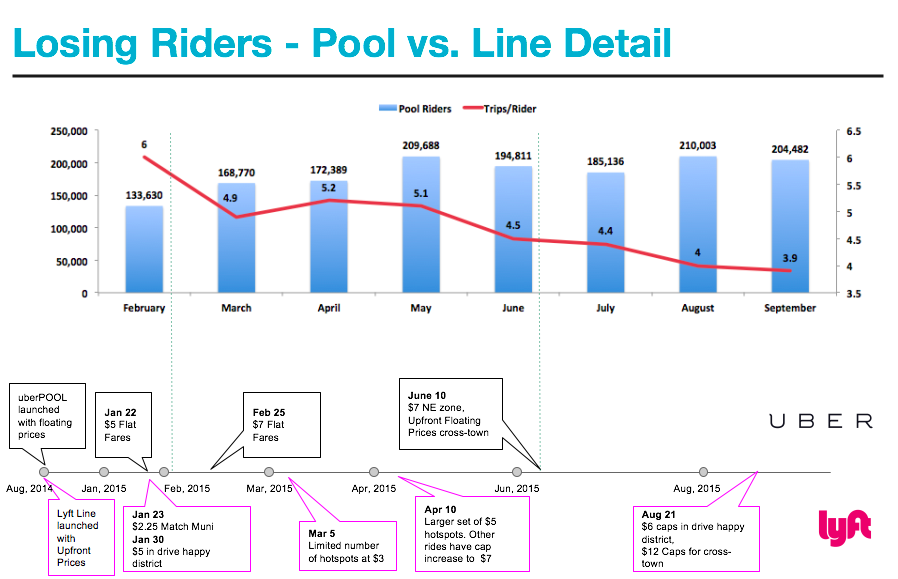

But when Uber cut the heavy discounts, ridership tanked. Sixty-three percent of riders moved on to cheaper alternatives, according to internal Uber data, and 26% migrated to archrival Lyft’s Line. Uber was, as a November 2015 internal presentation somberly concluded, “Losing SF.”

Uber — which at that point had expanded to more than 50 countries and had a rumored valuation of $50 billion — was ascendant. But it was struggling to attract riders to Pool, a service it considered crucial to the company’s future. Uber’s struggle to make Pool viable in San Francisco offers a case study of the ride-hail juggernaut’s burn-now-and-figure-it-out-later corporate ethos at a moment when it is still struggling to pinpoint a sustainable business model. Uber reportedly lost $2.8 billion in 2016, and at least $2 billion in 2015.

Uber declined comment on Pool figures obtained by BuzzFeed News.

Uber introduced Pool in San Francisco on Aug. 5, 2014 — a day ahead of the launch of Lyft Line, a similar ride-sharing service from its pink-mustached rival. An internal Uber policy memo from the time celebrated Pool as “an engineering marvel."

Uber CEO Travis Kalanick would later describe Pool as a key evolution of Uber's strategy. “Two people taking a similar route are now taking one car instead of two. And when you chain enough of these rides together, you can imagine a perpetual trip — the driver picks up one customer, then picks up another, then drops one of them off, then picks up another,” Kalanick told employees in June 2015.

If it’s working as designed, Pool is efficient — a way for drivers to spend far less time searching for fares, and for Uber to maximize drivers’ time. But for Pool to work, every “master” — the company’s internal code name for the first passenger in a Pool ride — requires second and sometimes third riders called “minions.” Pool also requires a critical mass of passengers and drivers to be able to match masters and minions headed on similar routes. For each trip in which a master isn’t matched with at least one minion, Uber loses money. The company told BuzzFeed News it now refers to masters and minions as “primary” and “secondary” passengers.

“It was a really shitty product we brought to market."

“Match rate is key,” a former Uber employee who worked on Pool in another major US market told BuzzFeed News. “Burn is a direct result of a low match rate. The higher the match rate, the less the burn.”

When Uber first launched Pool in San Francisco, the service’s match rate was terribly low. According to internal metrics obtained by BuzzFeed News, just 3,600 of the 35,000 Pool trips completed in the week beginning Sept. 1, 2014, carried master-minion pairs. That's a match rate of just 7.9%.

“It was a really shitty product we brought to market,” a former Uber employee who worked on Pool told BuzzFeed News.

Over time, Uber’s algorithms improved, and the Pool match rate inched higher. During the week beginning Jan. 5, 2015, nearly 42,000 riders took Pool, and nearly a quarter of those trips were matched with minions, according to internal documents.

But that wasn’t good enough. Uber and Lyft were battling it out with discounts, each offering lower and lower fares to entice riders. The week of Jan. 19, 2015, Uber rolled out $5 flat fares for Pool. About 125,000 riders requested Pool that week — more than double the number who had done so the week prior. Of those, 44% were matched into master-minion pairs with other passengers.

"If you burn enough up front and get those economies of scale and enough people using it, then at a certain point you’re finally going to get to a place where you have enough demand density," a former Uber employee who worked on Pool in a major US market told BuzzFeed News. "Then you finally break even — or make a profit — despite offering these very low fares."

About nine months after UberPool’s San Francisco launch, in the week leading up to May 24, the service’s match rate reached 60%. But that increase came at significant cost: “total burn” of $1.5 million. Uber was throwing cash into an incinerator to convince San Franciscans to ride Pool. The company reached a breaking point on the issue.

“HQ was telling us we could not be burning the amount of money we were,” one former employee said. “We couldn’t just give out subsidies that high anymore.”

As of June 2015, Uber had spent $6 million per month to “get UberPool right,” one internal memo said, referring to the burn rate.

On June 10, Uber broke its price war with Lyft. After months of flat fares for Pool rides across San Francisco, Uber dramatically reduced its $7 flat-fare zone to the northeastern corner of the city. The average Pool fare increased from $7.64 the week of June 7, 2015, to $9.44 the week of Aug. 23 that year, according to internal documents.

Almost immediately, the financial impact was clear. In the week prior to the price hike, Uber burned an average of $4.93 per Pool trip. Afterward, the company was taking in about 90 cents per trip, after accounting for driver payments and promotional spending.

But the price hike caused a sharp drop in ridership. Pool did just 184,000 trips that week, compared to nearly 235,000 the week prior when prices were lower.

“Every time we did something to reduce burn, our ridership went down,” a former Uber employee told BuzzFeed News. “The riders were just so used to getting discounts.”

An Uber presentation from November 2015 hammered this point home: “SF is down 18% on Pool since uncoupling pricing from Line.”

To alleviate some of the financial pressure, Uber considered increasing its “safe-rides fee." That fee was publicly described as a surcharge to cover safety costs like driver background checks, but internally, Uber felt it could also be used to offset the cost of matching Lyft Line's pricing, according to a document obtained by BuzzFeed News. Increasing the safe-rides fee to $1.50 from $1.00 in San Francisco would help trim about $650,000 to $900,000 in burn costs from September through December, an internal analysis found. In October of that year, Uber raised the safe-rides fee to $1.35. (In February 2016, Uber agreed to rebrand its safe-rides fee as a booking fee as part of a false advertising lawsuit settlement. Uber told BuzzFeed News that the "safe rides" moniker may have appeared overly simplistic.)

But in fall 2015, Uber wasn’t just losing riders — it was losing drivers, too. Twelve percent of its most active drivers left the platform from July to November 2015 compared with just 3% from January to June that year. “To pull competitor drivers to our platform, we need to offer better earnings potential now that Lyft [trips per hour] is comparable,” an internal document noted. A survey of nearly 700 Uber's most active drivers drove the point home: “‘Power drivers’ are less engaged — at least half are driving on Lyft. Why? Better economics.”

Convincing drivers of the promise of Pool was no easy task. An "Uber Pool Sucks" thread on the UberPeople.net forum hosts pages and pages of complaints: "this uber pool crap is a nightmare for the driver and a losing proposition,” reads one. But Uber was resolute. “Pool pricing may appear like a fare cut to drivers, but we maintain that drivers will earn more with Pool than with UberX because their utilization rate is higher,” the company explained in an October 2015 policy memo. A 2015 analysis of San Francisco Pool trips seemed to bear this out. It found that drivers who accepted Pool fares drove about 5.8% more than drivers who did not for an hourly wage increase of about $2.40.

"You would have to make some ridiculous assumptions to arrive at that number."

But former Pool managers told BuzzFeed News Uber’s math here was perhaps a bit too optimistic. “You would have to make some ridiculous assumptions to arrive at that number,” said one who worked on Pool in another major US market. To reach such a figure, this person explained, Uber would need to base its calculations on extremes: a driver who accepts all Pool rides versus a driver who accepts none. “Quite frankly, it’s rather misleading,” the former employee said. (Uber later paid the Federal Trade Commission $20 million to settle allegations that it misled drivers about potential earnings. BuzzFeed News reported last June that the net pay for drivers in some markets is comparable to that of a Walmart worker.)

To ensure Pool’s viability, Uber needed to cultivate an endless supply of repeat customers. So that fall, it doubled down on its attempt to woo commuters away from their cars and public transportation — and to the Uber app. To do that, Uber considered an idea from Kalanick himself: a multicity “Give Up Your Keys” campaign through which people would exchange their old cars for Pool credits. That idea never came to fruition. But Uber also outlined a possible partnership with WageWorks that would allow commuters to pay for Pool with pre-tax dollars, which it later announced in August 2016. Since then, Uber has partnered with transit agencies and cities across the country to subsidize rides.

About three years after its debut in San Francisco, Pool is now in 34 cities across 12 countries.

“POOL works better the more people use it at the same time and at the same location. As a new product, we offer discounts to encourage riders to try it out,” an Uber spokesperson told BuzzFeed News. “We’re proud of how far we’ve come with POOL, where today in San Francisco riders choose it up to 50% of the time."

Uber is still locked in a bitter price war with Lyft — and now has additional competitors as well. In New York, the ride-sharing shuttle van Via has taken aim at the commuter market with $5 rides, and recently raised $100 million and expanded to Chicago and Washington, DC. Gett, a Tel Aviv–based ride-hail company that operates in 100 countries, recently purchased the New York–based Juno, combining their forces in the battle for more market share.

The battle is far from over. “Each ride-sharing market is sort of independently contestable city by city,” said Arun Sundararajan, a professor at New York University and author of the book The Sharing Economy.

Pool also serves as an early test for Uber’s bigger bet on the future of transportation: the idea that people will one day summon shared self-driving cars to get around.

“The justification in their mind is if you make that investment now … the investment will pay off. And the person who's the leader when that happens is going to be sitting on a multi-hundred-billion-dollar market,” Sundararajan said. “This is why they raised so much money, and why they’re spending it the way they are.”