On Sunday night in Las Vegas, 58 people died and hundreds were wounded in a hail of bullets that, according to a New York Times video analysis, rained down at a rate of more than nine per second. According to the Clark County Sheriff, at least some of the weapons found in the shooter’s hotel room were fully automatic, or had been altered to fire like a machine gun.

After the deadliest mass shooting in modern American history, there are renewed calls to ban assault weapons and large capacity ammunition clips.

Ask experts how to reduce the gun death toll, which exceeds 30,000 in the US each year, and you’ll get a confident answer: Background checks, combined with laws that require a permit to purchase a gun, seem to be effective policies.

But ask those same experts about assault weapons, ammo clips, and mass shootings, and they hesitate. While they are just as appalled as anyone else by how often the headlines are dominated by the latest atrocity, to them mass shooters still seem like needles in a haystack, too rare to provide definite answers. And with the gun lobby poised to pounce on any scientist who suggests new restrictions without cast-iron evidence, many are reluctant to stick their necks out.

“The problem with designing a study that will produce the evidence is that you need a lot of cases,” Jeffrey Swanson, a psychiatric epidemiologist at Duke University School of Medicine, told BuzzFeed News.

What’s more, experts don’t agree on what constitutes a “mass shooting.” Some count incidents in which four or more people died, echoing the FBI’s definition of “mass murder.” In 2013, Congress defined a mass killing as one with three or more victims. But the Gun Violence Archive takes a much broader view, counting incidents where more than three people were shot, whether or not anyone was killed. By its definition, there have been 273 mass shootings already in 2017 — about one per day.

Then there are debates over what sorts of shootings should be counted. Do you include incidents within families? What about gang-related killings? Or should you only count public, apparently indiscriminate rampages like the carnage in Las Vegas?

These difficulties explain why two leading public datasets on mass shootings, one compiled by Mother Jones, the other by researchers at Stanford University, give different numbers for incidents, deaths, and injuries.

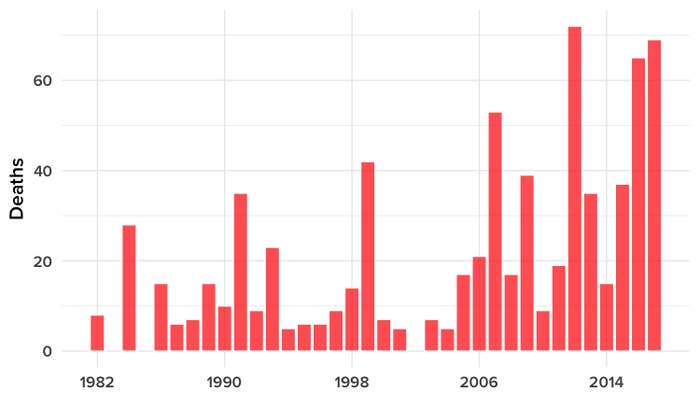

Still, by almost any definition, the toll from mass shootings is rising.

In September 1994, after an earlier spate of mass killings, the federal government banned the manufacture of certain semi-automatic assault weapons and clips holding more than 10 rounds. But the best-known study of the ban’s effects didn’t actually look at mass shootings. Instead, Christopher Koper, now at George Mason University in Virginia, concentrated on the use of guns in crime and the lethality of all gun attacks. Koper concluded that efforts to renew the ban after it expired in 2004, which ultimately failed, “are likely to be small at best and perhaps too small for reliable measurement.”

But Louis Klarevas, a researcher at the University of Massachusetts Boston, argues that the assault weapons ban did actually reduce mass shootings. In his book Rampage Nation, published last year, Klarevas focused on what he calls “gun massacres” — shootings in which six or more people were killed. “I wanted to look at the deadliest mass shootings,” Klarevas told BuzzFeed News.

Using his own database of incidents that met this criterion, Klarevas counted 155 deaths in the decade before the ban, 89 while it was in place, and 302 in the decade after it lapsed. In other, so far unpublished research, Klarevas looked at whether clips holding more than 10 bullets were used in these massacres. When they were, the average death toll was just over 10; otherwise it was a little more than 7.

For researchers studying public health, who are used to running rigorous statistical analyses on data involving thousands of people, these numbers may seem crude. But Klarevas, whose background is in homeland security and counterterrorism, where firm evidence is hard to come by, is happy to say that the assault weapons ban worked. “In my field, we do offer policy recommendations,” he said.

The best evidence on preventing mass shootings, meanwhile, comes from Australia. In 1996, after a series of massacres culminating in the death of 35 people in Port Arthur, Tasmania, the government banned a range of weapons including pump-action shotguns and semi-automatic rifles. It didn’t just prohibit new sales: Weapons already in circulation were made illegal, and bought back at a fair market price. In the decade that followed, there were no shootings in which five or more people were killed.

The US assault weapons ban, by contrast, only banned a narrow range of weapons, allowing manufacturers to evade the law by making small changes to their products. It also did nothing about weapons already in circulation.

Other gun violence researchers agree that limiting access to weapons that can unleash rapid fire should, in theory, reduce mass-shooting deaths. “Common sense suggests that the types of weapons and ammo available make a difference for how deadly the mass shootings are,” Philip Cook of Duke University told BuzzFeed News by email.

Indeed, when gun violence experts convened at Johns Hopkins University for a two-day summit in January 2013, just weeks after the Sandy Hook school massacre in Newtown, Connecticut, their policy recommendations did include a ban on high-capacity clips and a new, “carefully crafted” assault weapons ban that would be harder for gun makers to evade.

The next day, President Barack Obama called for the assault weapons ban to be reinstated. But Congress did not agree, and the current political climate seems even more hostile to the idea of banning an entire class of weapons.

“It depends upon the political and cultural will,” Daniel Webster, who heads the Center for Gun Policy and Research at Johns Hopkins, told BuzzFeed News. “I can’t say I’m optimistic.”

CORRECTION

The Las Vegas shooting on Oct. 1 was the deadliest mass shooting in modern US history. An earlier version of this story said it was the deadliest shooting in US history.

UPDATE

Updated to reflect revisions to the official casualty count.