After four years of the Trump administration’s “war on science,” scientific organizations celebrated the news last week that Joe Biden has picked Eric Lander, one of the world’s leading geneticists, to be his top science adviser.

The role will be Cabinet-level for the first time, making Lander arguably the most powerful scientist in American history. But some critics worry that Lander — whose career has been punctuated by aggressive moves against scientific rivals and a recent incident glorifying a scientist known for his racist and sexist views — comes with some baggage.

“You know, he’s a complicated figure. Let’s be clear, compared to where we’ve been for the past four years, it’s great,” Michael Eisen, a geneticist at the University of California, Berkeley, who has clashed with Lander in the past, told BuzzFeed News. “But the way he talks about things is very much about building himself and his institution up, often at the expense of others and the truth.”

Lander trained in mathematics and taught economics at Harvard Business School before switching to biology in the 1980s. As one of the leaders of the Human Genome Project, he pushed the effort across the finish line at the turn of the millennium. He has since turned the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, which he founded in 2004, into a powerhouse for applying a “big science” approach to biology. He served under Barack Obama as cochair of the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology.

Lander’s long track record of spearheading some of the most ambitious efforts in science has led many major scientific figures to applaud Biden’s choice. Marcia McNutt, president of the National Academy of Sciences, told the New York Times that Lander was “an inspired choice.” Harold Varmus, who chaired the PCAST with Lander, told Nature it was a “marvelous appointment.”

But Lander’s rise to power has been repeatedly marked by controversy.

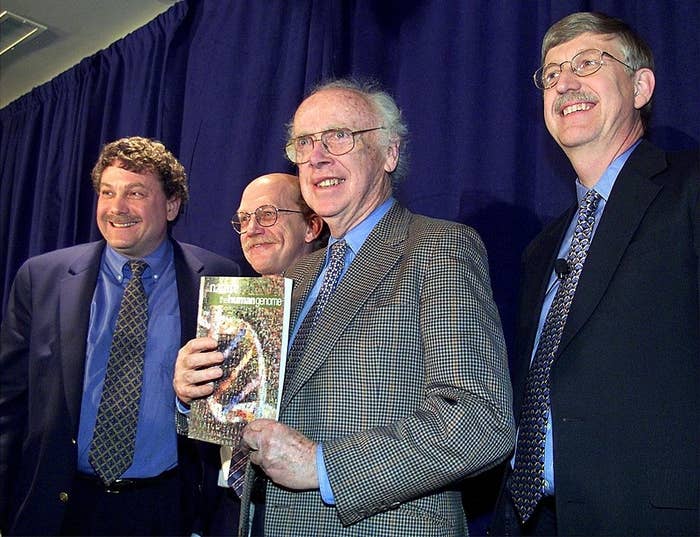

Lander was one of the main combatants in the “genome war” — the race between the publicly funded Human Genome Project and the commercial outfit Celera, founded in 1998 by Craig Venter to sequence the human genome in just three years.

By that time, the public project had already been toiling for around eight years, making a map of the human genome and dividing it up to be sequenced in pieces by many participating labs. Celera’s approach, dubbed the “whole genome shotgun,” promised a much faster timeline by breaking the entire genome into tiny overlapping fragments, sequencing them, and then using sophisticated algorithms to piece the entire sequence together.

Lander, then at MIT’s Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research, first argued that Celera’s whole genome shotgun wouldn’t work, then allegedly tried to strike a deal to collaborate with Celera, and later resumed his attacks on the company when the two projects finally published the human genome sequence in February 2001. Lander claimed that Celera couldn’t have completed its sequence without using mapping information from the public project and told a Nature reporter that the whole genome shotgun had delivered a “tossed genome salad” rather than an accurate readout of the human genome.

Still, Lander quietly retooled his lab to adopt Celera’s whole genome shotgun method when tackling the mouse genome, which he and others published in 2002.

Lander’s attacks stung Venter, who later revealed that Celera staff referred to their nemesis as “Eric Slander.”

“It was a war and tempers got really, really high,” said Robert Cook-Deegan, a specialist in science policy at Arizona State University, who has chronicled the science and politics of genomics. “Eric was one of the generals.”

Despite their high-profile dispute, Venter welcomed Lander’s nomination as science adviser, noting that he is the first biologist to be picked for the post. “I wholeheartedly concur that elevating science to a cabinet level position is the best thing for our country,” Venter told BuzzFeed News by email. “We’ve had 4 years without truth and a belief in science which is something I could never have imagined happening in the United States.”

More recently, Lander was charged with rewriting the history of the revolutionary gene-editing method CRISPR, highlighting the contributions of one of his own colleagues.

In response to his 2016 account in the journal Cell, critics charged that Lander downplayed the role of Jennifer Doudna of the University of California, Berkeley, and Emmanuelle Charpentier of the Max Planck Unit for the Science of Pathogens in Berlin, playing up the role of his Broad Institute colleague Feng Zhang. It came as Berkeley and MIT were involved in a bitter patent fight over CRISPR — a conflict of interest that Lander told the Scientist he had discussed with the journal, but was not disclosed in the article.

Doudna and Charpentier shared the 2020 Nobel Prize in chemistry for their work on CRISPR. They did not immediately respond to requests from BuzzFeed News for comment on Lander’s nomination.

In comments on the article at the time, Doudna called Lander’s account “factually incorrect” while Charpentier described it as “incomplete and inaccurate.” Jezebel covered the incident under the headline: “How One Man Tried to Write Women Out of CRISPR.” Doudna’s Berkeley colleague Eisen weighed in with a blog post that called Lander “an evil genius at the height of his craft.”

Following the incident, the biomedical news site Stat wrote that Lander had “morphed from science god to punching bag,” suggesting that the incident had released a tide of resentment from researchers struggling to win grants while Lander’s institute attracted vast amounts of federal and philanthropic funding.

Lander got in hot water again in 2018, when he led a 90th birthday toast to James Watson, codiscoverer of the double-helix structure of DNA, despite Watson’s long history of sexist and racist comments, including that Black people have genetically inferior intelligence. Calling him “flawed but strident,” Lander praised Watson for “inspiring all of us to push the frontiers of science to benefit humankind.”

Scientists blasted Lander for his comments, spurring him to apologize on Twitter and in an email to colleagues at the Broad Institute: “People who have called this out are correct. I was wrong to toast, and I’m sorry.”

In 2019, after Jeffrey Epstein’s arrest for sex trafficking and suicide in federal custody, photos emerged of Epstein talking to Lander and other Harvard and MIT luminaries at a 2012 meeting held in the office of Harvard mathematical biologist Martin Nowak, who had received millions of dollars in funding from Epstein. Lander, who has not been reported to have received any money from Epstein, told BuzzFeed News in August 2019 that he was invited by Nowak and did not know who was going to attend.

“I later learned about his more sordid history,” Lander said. “I’ve had no relationship with Epstein.”

In his remarks when introduced as Biden’s nominee for the top science adviser position on Jan. 16, Lander stressed his commitment to diversity in science. “After all, scientific progress is about someone seeing something that no one’s ever seen before — because they bring a different lens, different experiences, different questions, different passions,” he said. “No one can top America in that regard — but we have to ensure that everyone not only has a seat at the table, but a place at the lab bench.”

Karen James, a molecular ecologist at the University of Maine, who criticized Lander’s toast of Watson at the time, said she was encouraged that Biden has picked Alondra Nelson, a Black woman sociologist who heads the Social Science Research Council, as Lander’s deputy.

“Still, I would be reassured if Lander would publicly address these incidents again soon, in light of his new role, demonstrating that some self-reflection and learning has taken place,” James told BuzzFeed News by email.

Those who are close to Lander say that his strength lies in recognizing how to advance a scientific goal and then mobilizing people to make it happen. “Eric is very much an organizer of people,” his brother Arthur Lander, a developmental and cell biologist at the University of California, Irvine, told BuzzFeed News. “He likes to think about what can be accomplished, who can do it, and how can I twist their arms to do it.”

“You can’t separate what he can do positively from his style of leadership, which is very aggressive,” Cook-Deegan said.

Even Lander’s harshest critics accept that these qualities will be an asset in driving forward Biden’s scientific agenda in a difficult political environment.

“Certainly political skill and the ability to sell things at a high-concept level to the media and politicians is important, and Lander has that,” Eisen told BuzzFeed News. “But I do think that it’s important that people who are going to interact with him have some understanding of why he’s not a universally loved figure in science.”

In his appointment letter, Biden told Lander to focus on five sweeping areas: learning public health lessons from the coronavirus pandemic; harnessing science and technology to tackle climate change; ensuring the US can compete technologically, especially with China; guaranteeing that the fruits of science and technology are shared with all Americans; and ensuring the long-term health of American science.

Lander did not immediately respond to a request for comment from BuzzFeed News on previous controversies that have attracted criticism. Responding to news of his appointment on Twitter, he said that meeting Biden’s challenges would require teamwork between scientists, technologists, and the public.

Disclosure: Peter Aldhous teaches in the Graduate School of Journalism at the University of California, Berkeley.