Yuliana Ramírez learned she was pregnant in December 2016, about a month after splitting up from her boyfriend, Luis Diego Jiménez. She had no doubt Jiménez was the father, and as a dental technician in the Costa Rican capital of San José, Ramírez felt she would need financial support from him to help raise the child.

But Jiménez, the publisher of a sports magazine, demanded proof that he was the father before agreeing to pay child support. So in April 2017 the pair decided to get a paternity test, selecting a lab at the Hospital Clínica Bíblica, the largest private hospital in Costa Rica. It offered a test that could be run on a sample of Ramírez’s blood.

When the results came back more than two weeks later, the testing report said that Jiménez was “excluded as the biological father of the fetus.”

Ramírez had been depressed even before the test result. But after she got the report, she was “devastated, totally confused,” Ramírez told BuzzFeed News, in an interview conducted in Spanish in May of this year. “I could not keep working.” Jiménez wanted nothing more to do with her. Even her family doubted her, she said.

Under Costa Rican law, Ramírez was able to name Jiménez as the father and require another paternity test, this one run by an internationally accredited government lab after the baby was born. In November 2017, that test established with almost 100% certainty that Jiménez was the father.

Jiménez accepted the new result. While he and Ramírez are not back together, they now share custody of their child, and Jiménez is providing financial support. He told BuzzFeed News that he was happy to learn he had a son, but furious about what happened with the first test: “Very angry, first of all, because my son was born without the necessary support he could’ve had from the beginning.”

I spoke to Ramírez and Jiménez last month, in separate interviews via videoconferences from the offices of Linea Law, the firm that is seeking compensation for them from the private hospital that offered the test, Clínica Bíblica.

Ramírez and Jiménez didn’t know this when their samples were taken, but the test wasn’t run by Clínica Bíblica. Instead, it contracted out to a local lab called CEDIMEG, which in turn sent the samples off to a company in Toronto called the Health Genetic Center (HGC), also known as the Prenatal Genetics Center.

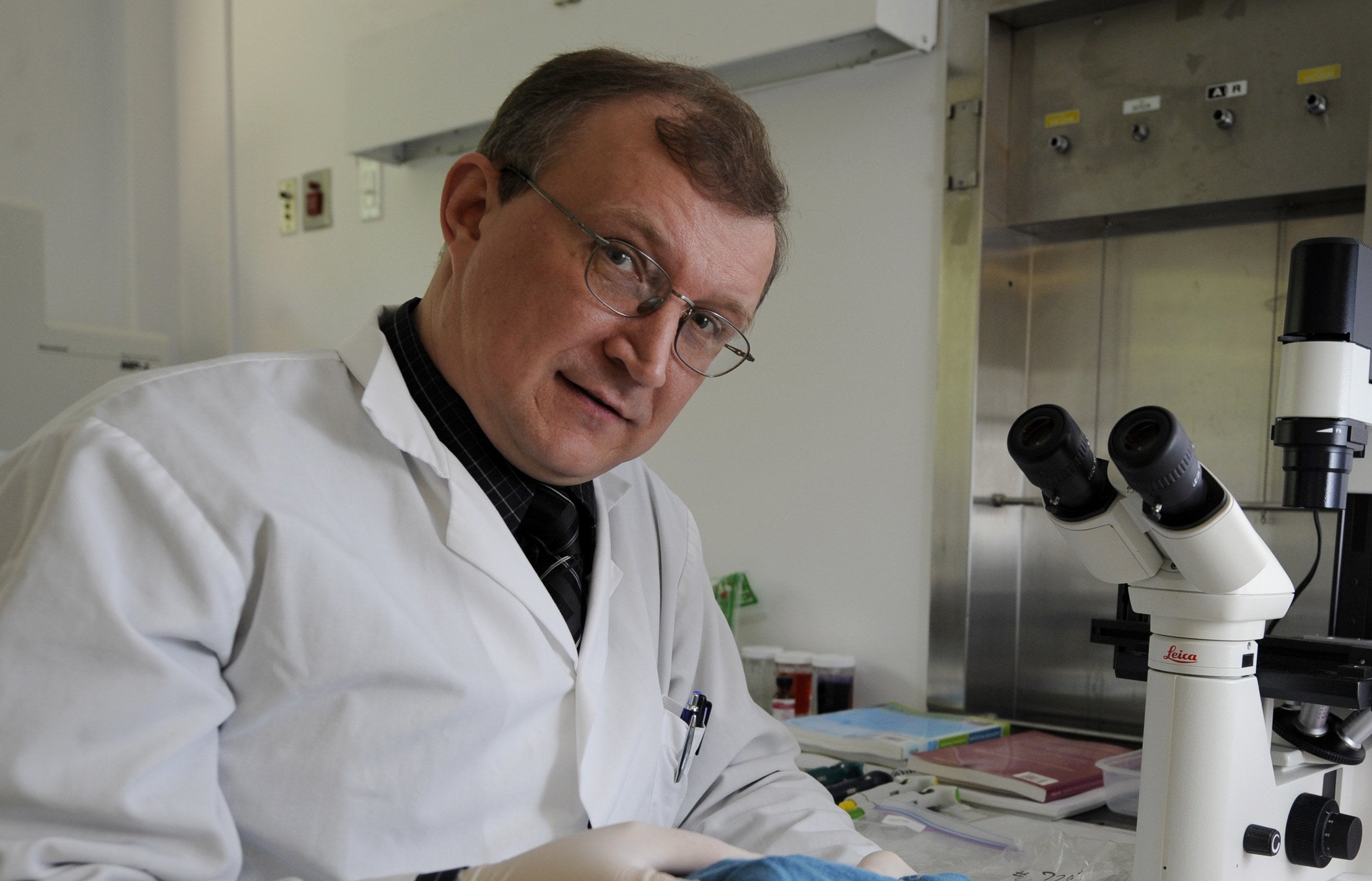

I know those last two names all too well. Almost a decade ago, while working for New Scientist magazine, I published an investigation into HGC’s prenatal paternity test. I spoke to women whose lives were upended by incorrect results and spent months dissecting the test’s serious scientific flaws. Shortly after my article was published in December 2010, HGC and its CEO, Yuri Melekhovets, sued for libel, setting up a long legal battle that finally came to an end in April this year.

In December 2018, I was vindicated in a ruling from a Canadian court. “No matter how damaging or disparaging it may be to the plaintiffs, the truth can never be actionable,” the judge wrote, concluding that the criticisms made in my original article were justified.

“Yuri Melekhovets, for all his claiming to be a dedicated scientist, did not behave like one,” the judge wrote.

But Melekhovets wouldn’t give up. He and HGC filed an appeal, claiming the trial judge was biased — focusing in particular on an incident in which my defense counsel offered him cough drops when he was feeling unwell. When that appeal was thrown out in December 2019, Melekhovets and HGC sought leave to appeal to the Supreme Court of Canada. That was denied on April 23, finally bringing the case to a close.

But I can take little satisfaction from this victory for investigative science journalism while I know that the test is still on sale. Customers thought the test was backed by rigorous science. The court ruled that it wasn’t.

“The evidence is overwhelming that the science necessary to confirm the assertion that the test was reliable and accurate was not done,” the judge in my trial wrote.

The DNA testing industry is largely unregulated. In the US, Canada, and other countries, companies are allowed to sell DNA tests without going through the approval process required for prescription drugs or medical devices. They don’t need to provide any scientific data confirming that a new test, whether used for medical diagnosis or to prove paternity, actually works as advertised.

If a DNA test is used to prove paternity in court, then a lab will need accreditation from a body such as AABB, formerly the American Association of Blood Banks, which provides some quality control. But what’s sometimes called “peace of mind” paternity testing, done outside of a legal setting, is a free-for-all that potentially puts unsuspecting customers at risk.

My protracted legal battle shows that this needs to change.

DNA paternity tests change lives. Based on the results they receive, couples may decide whether to stay together or split up. A child can gain a father, or lose one. The DNA tests may lead some women to decide to terminate their pregnancies. There should be no room for error.

So in 2009, when one of my regular expert sources, Denise Syndercombe Court, a forensic geneticist now at King’s College, London, told me that she had performed prenatal paternity tests for two women who had been considering abortions that contradicted results provided by a lab in Canada, I felt obliged to investigate.

If a pregnant woman wants to take a paternity test, the conventional approach is to sample cells from the fluid or tissue surrounding the fetus, which carry its DNA. That profile is then compared to DNA from cells swabbed from the cheek of a possible father. The problem is that the invasive procedures needed to sample fetal cells have a small chance of triggering a miscarriage. HGC’s test, by contrast, promised to give an answer by safely drawing blood from a pregnant woman’s arm.

One of the women who ordered the test, called “Kathryn” in my original article to protect her privacy, told me that she was going to abort the fetus she was carrying, based on the result provided by HGC. “I said to my counsellor that there’s absolutely no way I can go through with this pregnancy if it’s that guy’s,” she said.

But nagging doubts about the results caused her to contact Syndercombe Court for a second test, done by sampling fetal cells from her amniotic fluid. It revealed that the father could not be the man identified by HGC.

Over the months that followed, I found more customers who’d been given paternity test results from HGC that were subsequently contradicted by labs with the accreditation to perform court-directed paternity tests.

Although a pregnant woman’s blood does contain some fetal DNA, it’s in a mixture that is dominated by the woman’s own DNA profile. That makes it hard to detect fetal DNA from the blood alone — but not impossible. Today, two companies, the DNA Diagnostics Center (DDC) of Fairfield, Ohio, and Ravgen of Columbia, Maryland, market noninvasive prenatal paternity tests in the US. Both have published peer-reviewed scientific validation studies and DDC has also obtained AABB accreditation for the test. BGI, based in Shenzhen, China, published a validation study for a similar test in 2016.

But at the time my original article was published, in December 2010, HGC was the only company I could find worldwide that was running such a test. While several other websites were selling paternity tests using pregnant women’s blood, they all turned out to be brokers that ultimately sent the samples to HGC for processing.

Melekhovets had never published any data to show that his methods worked. In 2001, when he first put the test on sale, it relied on detecting the same genetic markers, known as short tandem repeats, or STRs, that are widely used in conventional paternity tests and in crime scene DNA analysis.

But when some customers turned to other DNA testing labs for a second opinion after the baby was born, they found that HGC’s results were inconsistent with follow-up tests run using the same markers. And in 2003, two such customers, Milan Jeknich and Kimberly Robbins, won a default ruling from a court in Arizona against another of Melekhovets’ companies called HealthGene, over a result that falsely identified Jeknich as the father of Robbins’ son.

Robbins had a credit card bill detailing payment to HealthGene, which processed payments for HGC. But Melekhovets took no responsibility, replying to a letter from the pair’s lawyer saying that HealthGene was a veterinary testing company. He didn’t show up to defend the case, and because he’s based in Canada, Jeknich and Robbins ultimately gave up on collecting the damages awarded by the Arizona court.

Testifying in my libel case, Jeknich wept as he recalled how he was devastated by learning that he was not actually the father of Robbins’ child. “I felt like somebody who had their baby switched at the hospital,” he said.

After 2006, Melekhovets abandoned STRs and began running his tests on genetic markers called single nucleotide polymorphisms, or SNPs. In his court testimony in my libel case, Melekhovets conceded the earlier test using STRs was “not sensitive enough to detect presence or absence of fetal DNA.”

When I looked at testing reports using SNPs, it was clear that his revised test still had serious problems.

First, he used too few SNPs to provide statistically meaningful results. Syndercombe Court testified in my trial that you would need to test “about 50” SNPs to reliably determine paternity, rather than the 10 to 12 shown on HGC’s testing reports.

The results came back with a DNA profile for the nonexistent fetus, and indicated that I was its father.

Kathryn and other customers who sought follow-up tests from labs using conventional methods again got results that contradicted HGC’s conclusions. And experts told me that some of HGC’s testing reports were scientifically implausible because the results were inconsistent with the known evolutionary history of the Y chromosome, which is passed from father to son.

Posing as customers to conduct my investigation at New Scientist, we sent in a blood sample from my editor (a woman who was not pregnant), plus cheek swabs from a male colleague and I. The results came back with a DNA profile for the nonexistent fetus, and indicated that I was its father.

All of this evidence — and more — was heard in March and April 2018 in the Ontario Superior Court of Justice in Toronto. Well before trial, my lawyers obtained a court order giving our main scientific expert, Bruce Budowle of the University of North Texas Health Science Center in Fort Worth, access to HGC’s lab, its testing protocols, and results from studies that Melekhovets claimed had validated his test. It was the first time that any independent scientist had been able to scrutinize his work.

Budowle found that the studies “would not satisfy any accepted standards for validation testing.” What’s more, as the judge explained in his ruling, HGC routinely ran a DNA-copying reaction known as PCR through many more cycles than the maximum recommended number. That increases the risk of errors, for example by copying tiny quantities of DNA from the environment that happen to contaminate a sample.

During the trial, Melekhovets treated our witnesses’ scientific challenges to his test with disdain. “I don’t need to convince other scientists how good this test [is],” he said. He called Budowle, a pioneer of forensic genetics who until 2009 was the FBI’s leading expert in DNA testing, an “office person.”

But he offered little in the way of scientific evidence to dispute my conclusion that HGC was marketing a flawed test giving unreliable results that had devastating consequences for some of its customers.

“There is no evidence other than the unsubstantiated claims of Yuri Melekhovets that the test works,” the judge concluded.

No evidence. Seeing these words in the ruling makes my blood boil, given the costs in time, money, and human suffering that Melekhovets and HGC have caused.

Valuable court time was squandered. My former employer’s insurer is now trying to recover legal costs of more than $1.5 million Canadian (about $1 million US) awarded against Melekhovets and HGC. Even if my lawyers are successful in that quest, it won’t cover the full sum spent defending the case. New Scientist’s managing editor, Rowan Hooper, testified at trial that the legal action had a chilling effect on the magazine’s journalism, making it less inclined to pursue investigations.

But what really makes me mad is that “no evidence” was enough for Melekhovets to sell his unreliable test to thousands of customers — causing untold harm.

In her affidavit, Tatiana Volossiouk, Melekhovets’ wife and HGC’s laboratory manager, testified that she had performed about 3,000 of the tests. “It is impossible to know how many of these tests are inaccurate and wrong,” the judge wrote. “Those affected may never know. They may find out years in the future.”

Contacted by BuzzFeed News, Melekhovets rejected the evidence heard in my libel trial and threatened to sue me again. “The judge, who barely understands the basics of biology, in his decision gives me advice on how the prenatal test should work and how to do science,” he wrote in a statement sent by email. “It’s the same thing as if I gave him advice on how he should conduct legal proceedings.”

Linea Law is now trying to negotiate compensation from Clínica Bíblica for the incorrect result Ramírez and Jiménez received in 2017. Their son’s third birthday is later this month, but his development has been slow, and Ramírez said he still hasn’t started talking. While the law firm isn’t blaming the child’s problems on the incorrect test result, it wants Clínica Bíblica to provide monetary compensation and ongoing medical care.

Clínica Bíblica did not respond to requests for comment from BuzzFeed News.

Linea Law ordered another paternity test from CEDIMEG, the local lab that sent the samples to HGC, in January 2019. This time CEDIMEG sent the samples to DDC to run a conventional paternity test, which again concluded that Jiménez was the father.

Melekhovets said in his statement that the wrong result could have been caused by a mixup of the samples in Costa Rica. “This is likely because it could turn out that the samples from the alleged father that CEDIMEG sent to us for the prenatal test and the samples that were sent to another laboratory are from two different people,” he said.

CEDIMEG declined to comment on the initial incorrect test result from HGC. “Since 2018, we do not have any commercial or professional relationship with the company,” Carlos Santamaría, its director, told BuzzFeed News by email.

“[O]ur CEDIMEG laboratory complies with the strictest standards of good laboratory practice, which includes the respective custody of the different samples we process,” Santamaría said.

If we don’t want unproven DNA tests to become the snake oil of the 21st century, we need something similar to drug approval for genetic testing.

The harm suffered by customers of HGC and its brokers who have received incorrect test results can’t be undone. What’s needed, to prevent this happening again, is a regulatory system that treats DNA tests more like drugs or medical devices.

Accreditation and quality testing for labs that sell genetic tests to the public should be mandatory. And before a novel test can be put on the market, its validity should be established through rigorous scientific trials.

There’s a precedent for more stringent regulation: New York State demands that DNA tests performed on its residents must be ordered by a doctor, attorney, or other qualified person, and be performed by a lab with a permit to run the test issued by the state’s Department of Health. That goes for paternity tests as well as for medical testing.

Before the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, snake oil merchants roamed the US with impunity. The act paved the way for the FDA’s role as the gatekeeper to bringing a new prescription medicine to market. If we don’t want unproven DNA tests to become the snake oil of the 21st century, we need something similar to drug approval for genetic testing.

But don’t just take it from me. Take it from Kathryn and her daughter, nearly aborted as a fetus. Take it from Jeknich, reduced to tears on the witness stand as he recalled his emotional roller coaster from more than 15 years before. And take it from Ramírez and Jiménez, still struggling to gain compensation for the error that caused their son to enter the world without a father. ●

UPDATE

Updated to clarify that Bruce Budowle is at the Health Science Center of the University of North Texas.