“I think it's very cruel to bring up the past,” says “Little” Edith Bouvier Beale in the new documentary That Summer. “To dig up the past I think is about the most cruel thing anybody can do.” The line is rich with layers of meaning, not least because Edie has become a symbol of nostalgia and bygone times through the cult classic nonfiction film Grey Gardens. That Summer, in theaters May 18, is being described as that film’s “prequel,” a word more often applied to blockbuster franchises, yet it’s an apt description that gestures to the enormous impact and influence Grey Gardens has had since its release in 1976.

Before reality television was mass-producing voyeuristic glimpses into the lives of hoarders and feuding pseudo celebrities, the cinema verité depiction of the mother-daughter duo of “Big” and “Little” Edie Beale — an aunt and cousin of Jacqueline Kennedy living together in the dilapidated Hamptons mansion of the title — achieved iconic resonance and has come to act as shorthand for evoking lost high-society splendor. These women might have been erased from history, but after their family money disappeared, their 28-room home became an eyesore, and in 1971 a “raiding party” of Suffolk County officials visited multiple times to investigate supposed health code violations. The event prompted tabloid headlines about the duo’s Kennedy adjacency — “Jackie’s Aunt Told: Clean Up Mansion” — and eventually sparked the interest of filmmakers Albert and David Maysles, who turned their lives into a documentary.

The brothers’ resulting slice-of-life portrait doesn’t offer any objective explanations of the Beales’ past, focusing instead on their creatively eccentric everyday existence. We watch as they fashion shirts into skirts, feed visiting raccoons (with Wonder bread), and sing and dance to old waltzes and show tunes. They also debate — with the passion and wit of 10 Real Housewives reunions — their often competing accounts of their life stories before ending up in Grey Gardens.

The carefully limited scope of the film, and the way it seems to preserve the Beales in the cinematic amber of the moments we spend with them, has left viewers with endless questions: How did they end up there? Did the squalor mean they had a mental illness? Was Little Edie a prisoner of her dominating mother? But it also allowed the public to interpret the women’s lives as tragic or triumphant at will, and the meanings of their story have been contested and celebrated ever since in countless forms, from an award-winning Broadway musical and movie to a Real Housewives storyline and RuPaul’s Drag Race skit.

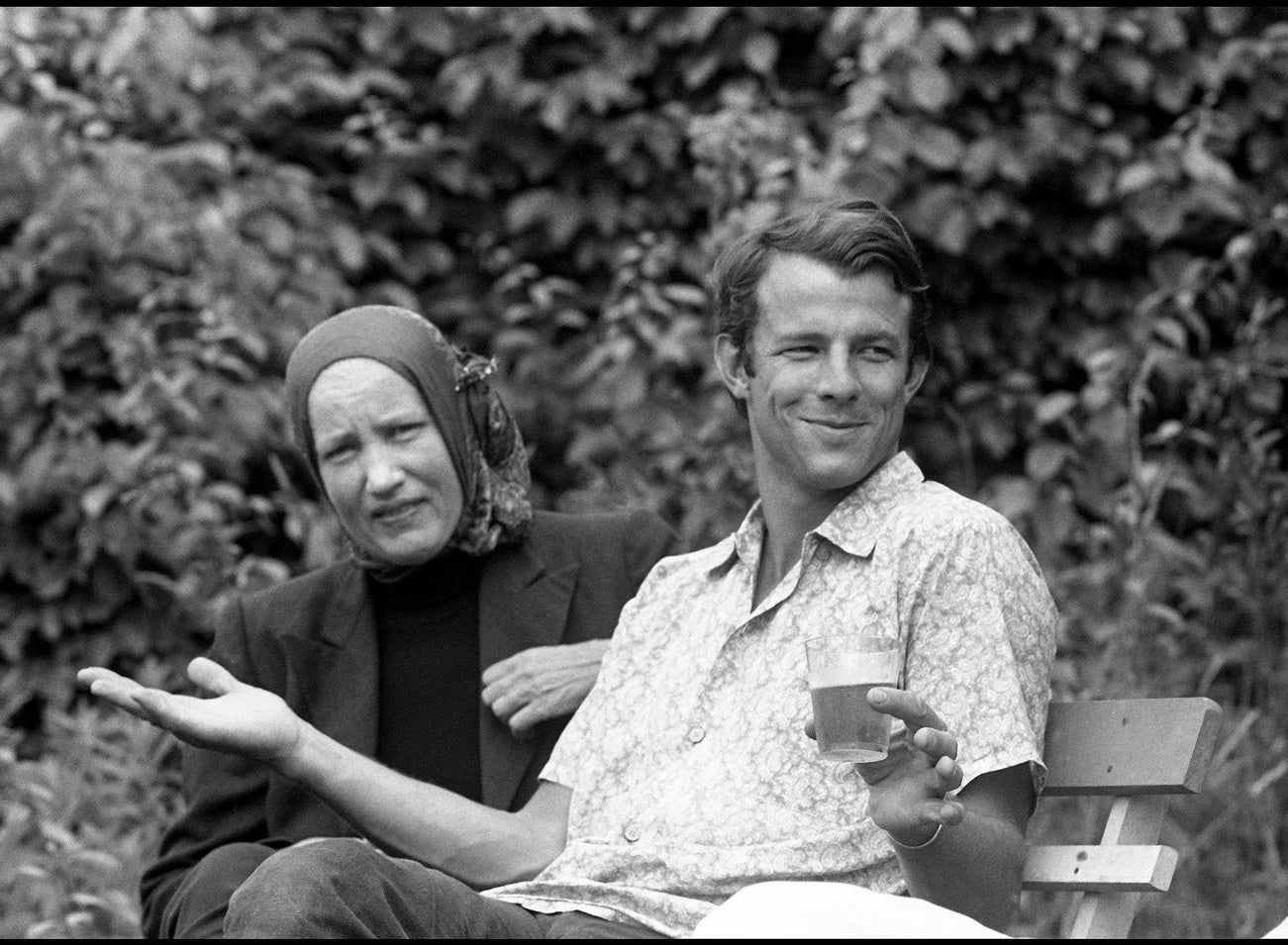

Given the amount of attention and interpretation they’ve been subject to, it might seem that there is nothing new left to say about the Beales. That Summer sidesteps this issue by delicately circling around them, through fresh found footage of Jacqueline Kennedy’s sister, Lee Radziwill, visiting her relatives during the early stages of what was originally intended to be a film about her nostalgia for her childhood Hamptons, shot by the Maysles brothers and Peter Beard, a New York photographer in Andy Warhol’s circle. That Summer was compiled primarily from that footage by the Swedish filmmakers of the critically lauded documentary Black Power Mixtape 1967–1975, and this new film speaks to our collective ongoing fascination with the Beales and the canonical status their story has achieved.

There’s no doubt that the documentary’s promotion trades on that fascination; “this is a gift to film lovers of the world, especially those of Grey Gardens,” executives from distributor IFC told the Hollywood Reporter. But That Summer provides little new information about or deeper understanding of the Beales, at least in the way that the idea of a “prequel” suggests. It offers, instead, the wonder of returning to their peculiar and enchanting lost world at a moment before they — and Grey Gardens — had become the powerful symbols that continue to resonate in pop culture today. And it reminds us that what has kept so many people fascinated by the women of Grey Gardens since 1976 is the ambiguous way the film can both evoke the idea of delusion, so often used to dismiss women’s stories, while also representing the possibility of reclamation and self-determination. There are no clear answers to be found in revisiting the world of Grey Gardens, but the questions it raises refuse, as Little Edie might say, to stay in the past.

“It’s very difficult to keep the line between the past and the present” is a phrase Little Edie utters early on in Grey Gardens, in a moment of seemingly sudden realization, and it arguably became the film’s most iconic line. The appearance of a similar sentiment in That Summer is not an accident, because it has come to neatly condense the idea of lost glamour and nostalgia that the documentary came to represent. The film itself, however, isn’t mostly a look at the past; instead, it emphasizes the Beales’ agency in constructing the story around themselves.

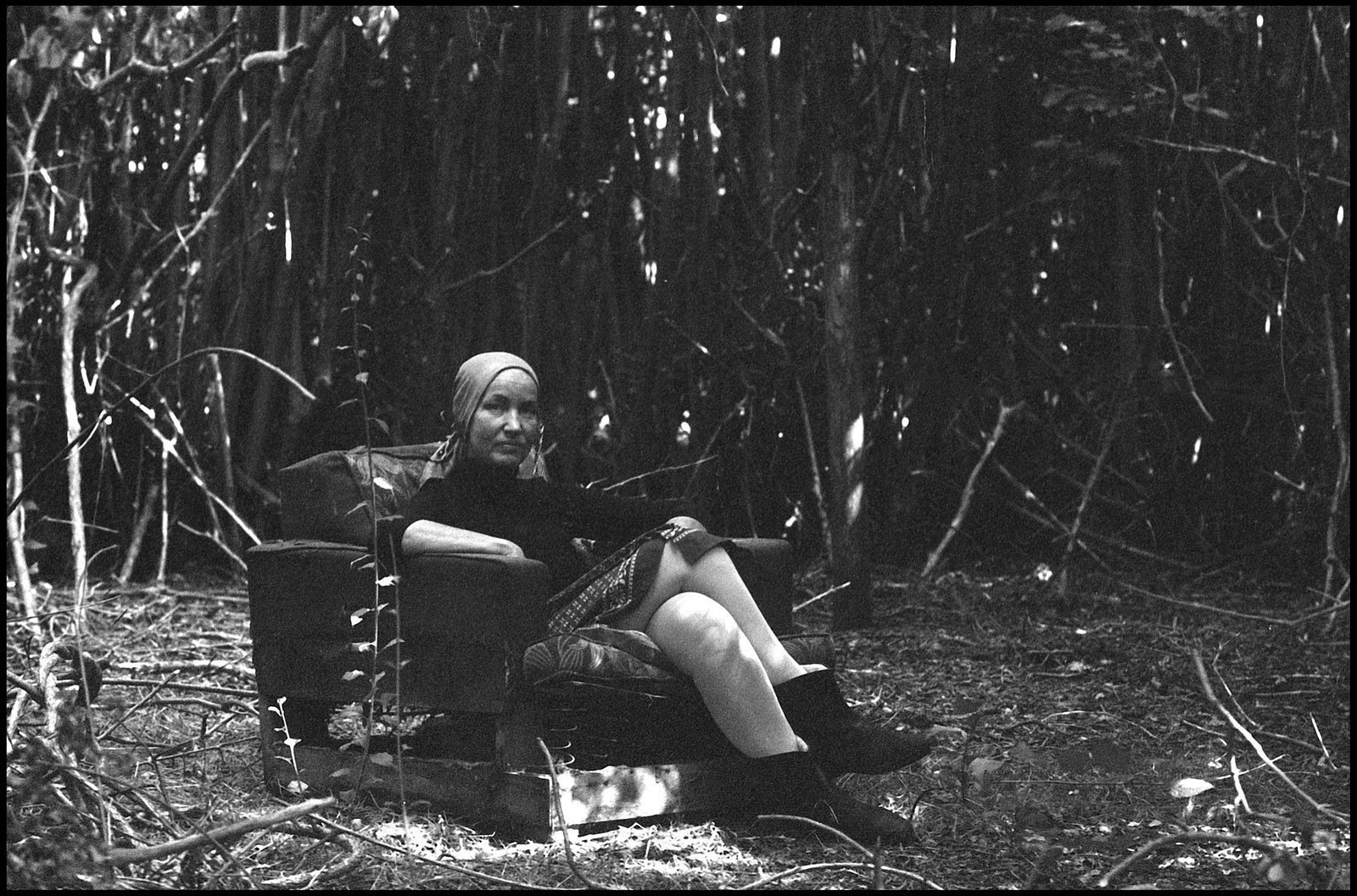

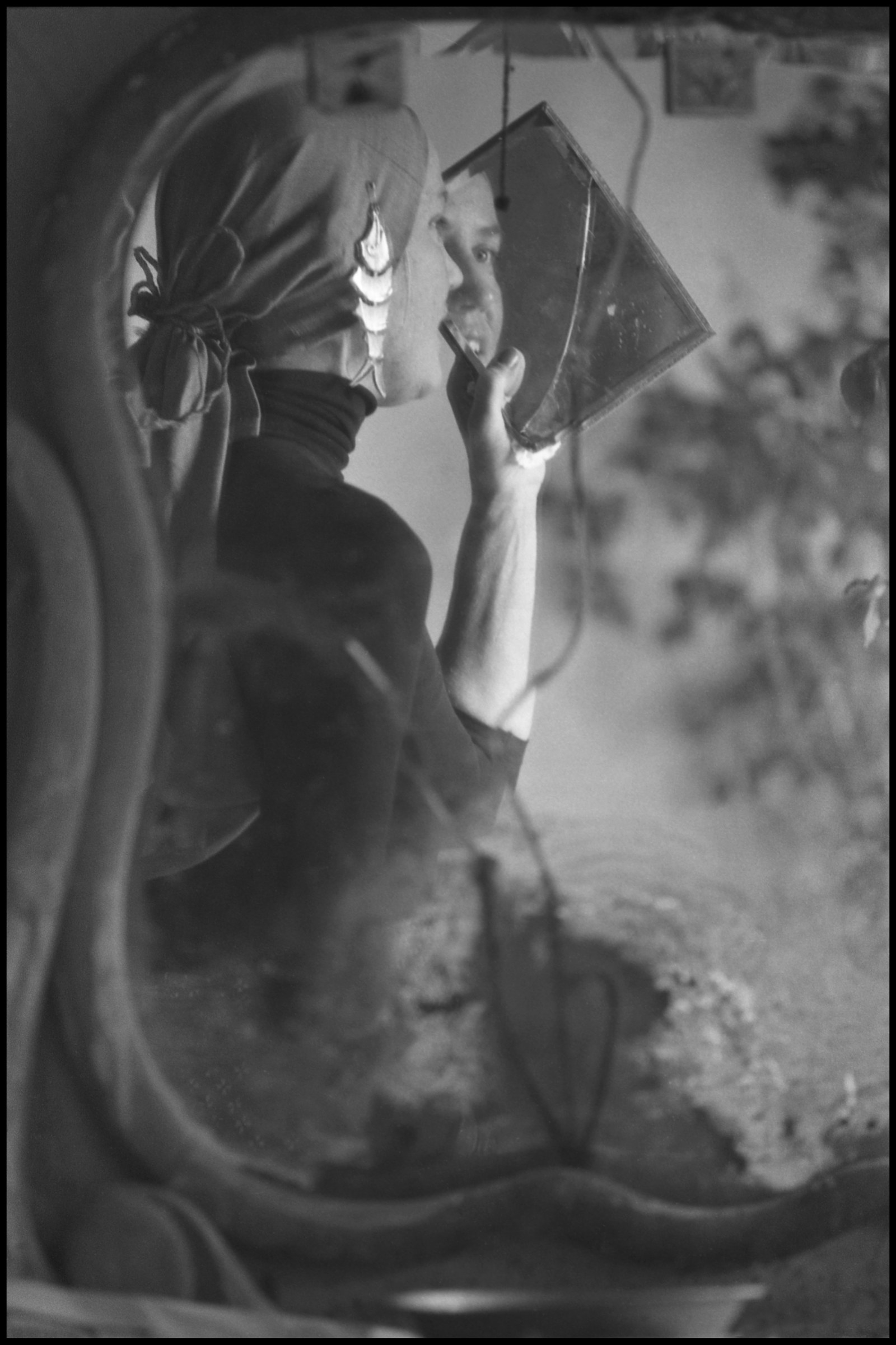

It is Little Edie’s expressive face, looking unimpressed, in her glamorous headscarf and fur coat — self-fashioning is a big part of her appeal — that adorns the movie poster for Grey Gardens. And in many ways, Little Edie is the central voice of the film, as she whispers conspiratorially, and even flirts, with the filmmakers. One of the most celebrated and re-created moments comes as Edie considers her younger life and her battles with her father and family conventions. “In dealing with me, the relatives didn’t know that they were dealing with a staunch character,” she explains, savoring the word “staunch,” which she then spells out, in her parodiable Brahmin accent. Staunch women, she says, “don’t weaken, no matter what.”

Part of the reason for Grey Gardens’ continuing circulation is that the stories the women told — about themselves and their relationship — raised deep, still fiercely debated questions about women’s lives more generally and the competing demands placed on them as caregivers, wives, and daughters versus their desires for artistic pursuits.

“I came here to take care of my mother. I was sick and tired of staying up worrying about my mother,” Little Edie explains about why she left Manhattan and a potential acting career to stay in Grey Gardens. “It’s a good thing you had a place to come to — recuperate at mama’s,” retorts Big Edie, portraying herself as the selfless caregiver. “She just didn’t wanna get married,” Big Edie explains, “and it was all blamed on me.”

The dialogue between the two women, and between them and the filmmakers — who include snippets of their own speech, egging the Beales on in their performances and discussions — also created a space for viewers to chime in and come to their own conclusions. Were Big and Little Edie tragically deluded or eccentrically self-determined?

Ever since Grey Gardens was made, reviewers have raised questions about its protagonists’ self-awareness — or lack thereof — because they unsettled so many gendered conventions. In a 1976 review, “Cinéma Verité or Sideshow?” New York Times critic Walter Goodman was ambivalent about their depiction, suggesting that they were exploited by the filmmakers, and presented as “a pair of grotesques” in “pitiable circumstances and absurd poses.” Yet the absurdities that the reviewer highlights — Little Edie’s famous flag-waving Fourth of July dance march, Big Edie comfortably sunbathing — seem most notable today for being transgressions of what was then considered respectable behavior for women of their class and age (they were 77 and 54), rather than an objectively embarrassing invasion of privacy.

Goodman’s disapproving survey of “the sagging flesh, the ludicrous poses, the prized and private recollections strewn about among the tins of cat food” reveals the then- (and still) reigning belief that older women’s bodies should remain private and that a woman’s dirty house must be an embarrassment — or even a sign of questionable mental health. But in the film, the Beales seem unembarrassed by their own lives and by their observers.

At one point, one of the cats pees on a portrait of Big Edie lying on the ground. “Isn’t that awful?” asks Little Edie. “No, I’m glad someone’s doing what they want to do,” her mother replies. And the way the Beales did, in fact, seem to do what they wanted to, breezily defying cultural expectations, was a huge part of why Grey Gardens spoke to so many people — and to gay men, in particular.

Grey Gardens started becoming iconic among gay men through art house showings and eventual release on VHS. "It served as a kind of recondite, East Village version of camp, classical Hollywood," University of Sussex film professor John David Rhodes told the Advocate. "It was one of the films that all of us quoted to each other.” Thanks to this gay fame, Little Edie even performed a cabaret act at a West Village club in 1978.

In part because Big Edie died a year after Grey Gardens was released, it was primarily Little Edie, who died in 2002, who became the real-world star of the documentary’s ongoing afterlife. She is still referenced everywhere from Lady Gaga’s “Applause” music video to RuPaul’s Drag Race. These references are tributes to Edie’s ingenuity and avant-la-lettre minimalist chic fashion sense; like the documentary, they celebrate her defiant work of self-making despite her ostensible lack of resources.

Throughout the aughts, the story of Grey Gardens was also adapted in more “prestige” forms, like a 2006 Tony-award winning Broadway play — which has an entire song about Little Edie’s “revolutionary costume” — and a 2009 HBO movie starring Drew Barrymore and Jessica Lange. The HBO movie is more clearly in dialogue with the documentary and its afterlife, attempting to fill in gaps of information, trying to explain the glimpse of the Beales we see in Grey Gardens through their romantic disappointments and their lives before (and in Little Edie’s case, after) its release. The filmmakers are characters in this fictionalized version, and Grey Gardens the documentary becomes a kind of triumph, as if it fulfilled Little Edie’s ultimate dreams of fame; we see Barrymore happily performing her cabaret show in the closing credits.

But the mysteries the HBO movie sets out to solve with imagination were never so clearly addressed in real life by the Beales or their documentarians. Precisely because of the mysteries left in the wake of Grey Garden’s release and the women’s ensuing stardom, That Summer’s promise of a return to the scene of the documentary’s origins has already generated a lot of excitement; the Hollywood Reporter calls it “a must for fans of the Maysles' film.” Director Göran Hugo Olsson’s new film approaches the Beales obliquely rather than directly, offering glimpses of Big and Little Edie that reaffirm what we already know about them, rather than trying to construct a definitive narrative about what we don’t.

Like the original documentary, That Summer isn’t an attempt to explain how Big and Little Edie ended up in Grey Gardens, or to pin down their story into cause and effect; instead, it provides slightly more context about a planned film that preceded Grey Gardens. The title refers to the summer of 1972, which Lee Radziwill spent with Peter Beard in the Hamptons. Radziwill was initially interested in Beard making a film about her Hamptons memories, and she wanted the Beales — her cousin and aunt — to narrate some of it. This new documentary is constructed around recovered footage of the women shot by Beard at the time. Voiceover from Beard, who was interviewed for the documentary, and snippets of an interview Radziwill did with Sofia Coppola in 2013 contextualize the footage.

Like the Maysles brothers, Beard was fascinated with the Beales and disagreed with East Hampton officials’ attempts to frame the women as deluded or delinquent. “I never thought of the Beales as unfortunate or sad, except very excellent at feeling what it was like to hold on to the past,” he explains in That Summer, emphasizing their agency in the same way that the eventual portrait of Grey Gardens did. “They were in a dream world, and it was okay."

Radziwill, who got the women to open their doors to the filmmakers, also supports the understanding of the Beales as eager participants in the films made of them; she says, “The Beales were terribly attracted by the cameras, adored to have their picture taken.” In the found footage, we see Radziwill interacting with them as they deal with the house repairs that she and her sister arranged for, a reminder that the grimy house we see in the later documentary had already been fixed up.

In many ways the footage seems organized to echo the women’s later portrait — there are plenty of vignettes about their bickering and a performance of an old song by Big Edie. There are no clear new revelations, whether about mundane details of their life or their relationships with their family and neighbors, as Variety’s review points out. But some of the scenes of the women’s interactions with Radziwill in particular, who always speaks to them in a calm and understanding tone, provide a more intimate and less overtly performative view of them.

They are less the freewheeling, artistic eccentrics of the later documentary and are still in shock over East Hampton township’s 1971 raid of their house. Little Edie complains about the lack of power and being “always filthy dirty in your horrible house, you’re disgusting. I'll never feel right in this place, ever.” Big Edie tells Radziwill, who listens sympathetically, “You don’t know what that housing thing did to me. I was destitute. I had an awful winter, terrible winter; we had an awful time keeping things going here.”

Beard’s voiceover provides the most insight. He describes his time with the women as "the most wonderful visitation series I've ever enjoyed,” adding that there “was no bad side to it, ever.” In one scene, Lee Radziwill’s children visit the Grey Gardens raccoons. “That's why the roof went,” Big Edie says, “but we didn't care. We loved the raccoons.” And the children’s wondrous excitement is a poignant reminder of how the women’s disregard for conventions could look through different, less jaded, eyes.

“I just always see it as a very beautiful state of being on a flying submarine, on a spaceship,” Beard says. “It was just fantastic.” Were the women tragic or happy, delightful or delusional? By framing their fantastic world on their own terms, and not through the usual gendered tropes that would “explain” their actions, Grey Gardens threw those questions back at the public. And in letting them remain unanswered, the latest return to the film’s world reminds us of why its heroines remain — at least in our cultural imagination — so vibrantly alive. ●