The man known as the Butcher of Bega is hard to forget. Graeme Reeves was convicted of maliciously inflicting grievous bodily harm on a woman for removing her genitals without her consent in an operating theatre in 2002. Just as she was drifting off under anaesthetic he said to her: "I'm going to take your clitoris too."

Reeves was deregistered as a medical practitioner in 2004. Nobody would think that he ever could, or would, be registered as a doctor again.

But an investigation by BuzzFeed News can reveal Reeves was at risk of being registered by the very government agency tasked to protect the public from medical misconduct.

Documents obtained by BuzzFeed News unveil shocking failures in Australia's medical registration system that could have seen men like Reeves re-registered as medical practitioners, without any red flags being raised inside the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (AHPRA).

A draft internal briefing paper from AHPRA exposes serious flaws in Australia's registration system that could have seen criminals convicted of sexually assaulting and mutilating the genitals of patients re-registered without detection.

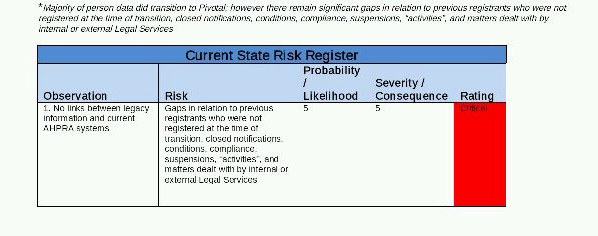

Prepared in September 2013, a concept paper titled "legacy data access" written by a staff member sets out a number of “critical” risks to the registration of practitioners with criminal records. And it reveals that the agency was at that time missing more than five million key documents that should have been passed over from state medical regulators.

A spokesperson for AHPRA told BuzzFeed News that "protecting the public is at the centre of everything we do". She said the agency has had access to all "legacy data" since 2010, and added that it had a "clear process" for checking these records.

Australia's current nationalised medical system was in part set up in response to Reeves' prosecution, and a number of other high-profile cases of medical abuse.

The outrage surrounding the crimes they committed triggered a public debate about more stringent national standards. Up until that point, medical registration requirements varied from state to state, so a single national agency – AHPRA – was established in order to oversee the thousands of medical practitioners working across the country.

This new system required the merger of disparate state registration boards for doctors, pharmacists, dentists, nurses, chiropractors, physiotherapists, and other medical professionals, who were all to be brought under the authority of one national organisation.

Many of these boards had been functioning for decades, and had made hundreds of findings of misconduct against medical practitioners leading to their suspension or cancellation. Because of the importance of these decisions, it was crucial that the information was handed over to AHPRA quickly and efficiently.

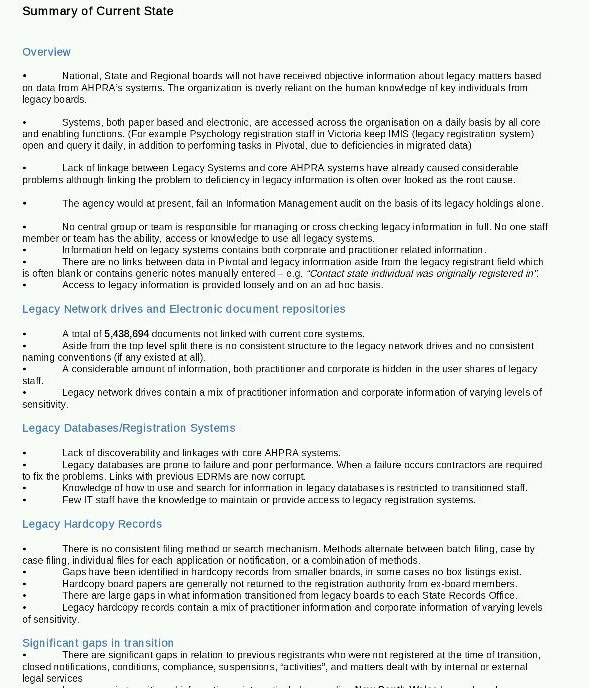

But that didn't happen. The internal briefing paper showed that the new national body struggled to manage the task of migrating decades of records of medical misconduct into one central system.

While a large amount of data was handed over in the lead-up to AHPRA's formation in 2010, the report noted that "there are significant gaps in relation to previous registrants who were not registered at the time of transition, closed notifications, conditions, compliance, suspensions, activities, and matters dealt with by internal or external legal services."

It assesses this as a "critical" risk for the agency with the highest possible severity rating. Information about historical sanctions against medical practitioners was "provided loosely and on an ad hoc basis". The author of the report also concluded that the organisation was likely to fail an information management audit based on these findings.

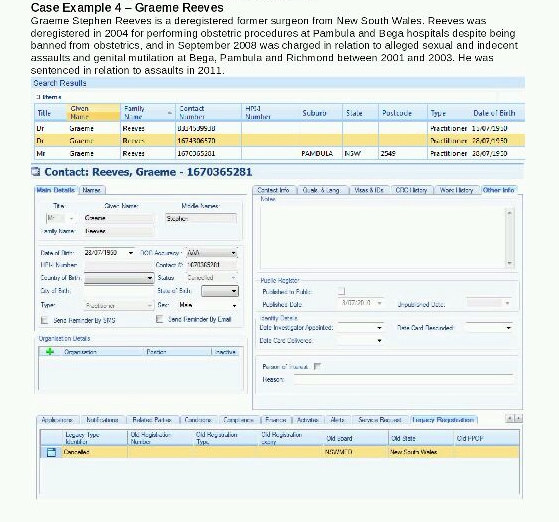

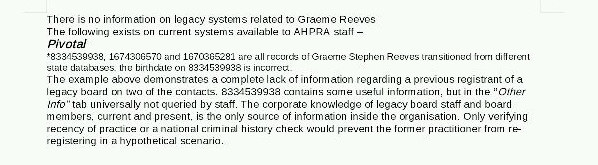

Graeme Reeves is used as a specific example in the report to illustrate the scale of the problem. The internal document shows several entries in AHPRA’s systems with Reeves' name that contain no details of his prosecution. “There is no information on legacy systems related to Graeme Reeves,” it said.

“The corporate knowledge of legacy board staff and board members, current and present, is the only source of information inside the organisation. Only verifying recency of practice or a national criminal history check would prevent the former practitioner from re-registering in a hypothetical scenario,” the document reads.

It is unlikely Reeves – who spent years battling court challenges linked to his medical career – would ever have attempted to register as a practitioner again. He was charged in 2015 with alleged manslaughter, and acquitted in November 2017. Outside the court he declared to reporters: "I'm dying."

But the briefing paper reveals that other medical practitioners convicted of serious offences could also have been registered as doctors again.

In June 2010 Jayant Patel was convicted of the manslaughter of three patients. In 2012 these charges were quashed by the High Court, and a retrial was ordered. He was acquitted of one count of manslaughter, and later took a plea deal where he pleaded guilty to four counts of fraud for dishonestly obtaining his registration in November 2013. The board banned him permanently as a medical practitioner in November 2015.

This was a complex case, but one in which serious concerns had been raised about Patel's conduct in the decade prior. He had previously been found to have engaged in serious professional misconduct in the United States by the Oregon medical board for "Gross or repeated acts of negligence in the practice of medicine" in 2000.

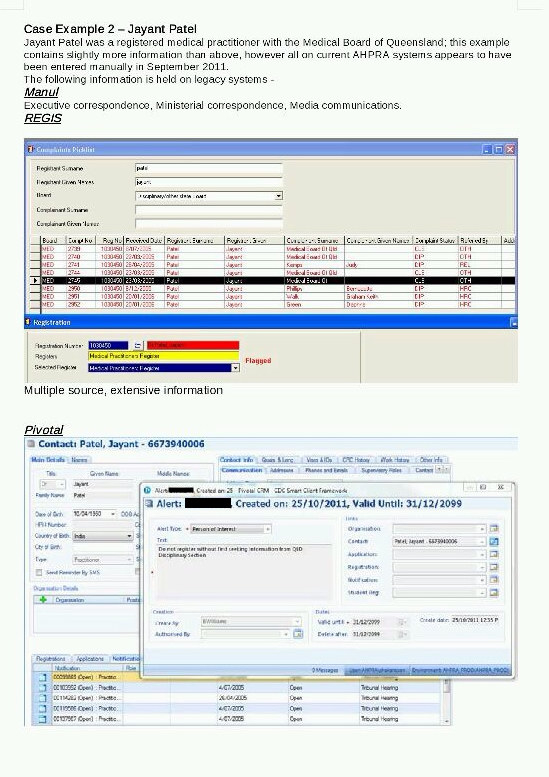

Despite the many public concerns about Patel, AHPRA's electronic systems held scant information at this time on his registration. Its internal systems only disclosed 10 "notifications", which are made when there is an allegation against an individual.

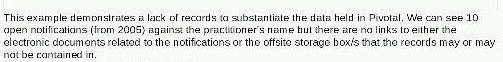

But the allegations of criminal misconduct and charges in court are absent; no context is provided. The report noted Patel's case “demonstrates a lack of records to substantiate the data held in Pivotal [AHPRA's record system]. We can only see 10 open notifications (from 2005) against the practitioner’s name but there are no links to either the electronic documents related to the notifications or the offsite storage box/s that the records may or may not be contained in.”

Aside from a brief note that advises staff, in the event that Patel applied for registration, to check with the state office before re-registering him, the report states "there is no other information widely available for AHPRA or the boards to make any information decisions should the individual decide to re-register in any state or territory."

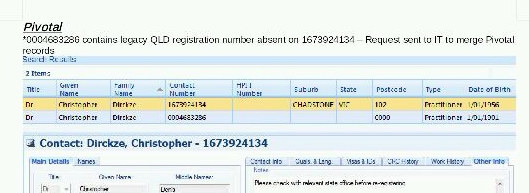

The internal report also looks at the registration of Christopher Dirckze. In 1997 Dirckze was de-registered as a medical practitioner in Australia after being found guilty of "infamous conduct". He was HIV-positive, and was found to have had unprotected sex with two current patients. He was found to have defrauded Medicare, misused the doctor-patient relationship to borrow money from patients, and encouraged an untrained person he knew was HIV-positive to assist in minor surgical procedures. Once again, AHPRA's own records reveal scant information about these historical events.

The greatest risk for the agency is that a medical practitioner who has been struck off previously may go undetected because of the poor state of recording. The internal report warns that failing to take any action puts AHPRA's work at risk and leaves open "a wide gap in relation to protecting public health and safety".

A number of critical concerns are identified on a risk register set out in the paper. This includes that “National, state and regional boards are unlikely to have received objective data from the system. Human knowledge from key individuals and the collective memory of the organisation appear to be the primary source of information.”

It also warns that "no one staff member or team has the ability, access or knowledge to use all legacy systems", posing further risks that historical sanctions against medical practitioners have not been updated.

Medical professions that employ fewer people are also a particular risk. The report said there are "large gaps" in information transitioned from professions including chiropractic, podiatry, physiotherapy, optometry, osteopathy, dentistry, and pharmacy. In a shocking finding, the report states that: "In some circumstances no legacy information transitioned.”

The report concludes: “The agency would at present, fail an information management audit on the basis of its legacy holdings alone.”

The paper sets out several options for improving the agency's handling of personal data and medical malfeasance files, some at considerable cost to the agency.

BuzzFeed News put detailed questions to AHPRA about the report's findings, the measures it proposed, and the concerns raised about the prospect of practitioners being re-registered.

A spokesperson for the agency declined to answer specific questions about the report.

She said in a written statement: "Protecting the public is at the centre of everything we do. This includes being responsible about how we collect, protect and use data."

She added that the agency had access to all legacy data since 2010 and "a clear process for checking legacy data whenever needed, such as every time someone who used to be registered before 2010 applies for registration, every time we receive a notification (complaint or concern) about someone who was registered before 2010 or when we issue certificates of registration status."

In relation to Reeves, Patel, and Dirckze, the spokesperson said: "As with all other practitioners who had been previously registered before 2010, we had access to the legacy information about the practitioners you named in your query since the National Scheme came in to effect."

But separate documents obtained by BuzzFeed News indicate a "small number" of medical practitioners have been registered in error since June 2010, including one practitioner who wrongly gained registration for a period of 11 months without detection by the agency.

It is not known whether any of these practitioners registered in error were able to obtain registration due to the record-keeping failures identified by the author of the first report.

The Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency is different from other federal government agencies. Because health is generally a matter for state governments, it was created by an agreement of the Council of Australian Governments. As a consequence, it is not a federal statutory agency and is not periodically scrutinised by parliament in the way that the Department of Health or Education might be.

In 2016 there was a push by parliamentarians to improve transparency around the medical complaints process. A Senate inquiry was convened, chaired by Greens senator Rachel Siewert, tasked with a broad remit to examine AHPRA and the handling of complaints by various medical boards. The inquiry made a number of recommendations to improve how AHPRA and the medical board handled complaints. In particular it noted that "the committee considers that there is scope for a broader investigation of the framework underpinning medical regulation in Australia".

It argued that a further Senate inquiry should be convened to examine the role of AHPRA and the various medical boards, and how they handled and resolved serious matters.

But the Australian government declined to accept this recommendation. In an October 2017 response it said that a number of reviews were already being implemented: "Work is

currently underway as a result of these reviews, in collaboration with jurisdictions and

AHPRA, to make improvements to the Scheme, especially in relation to notifications and

complaints processes".

Despite assurances that the agency is managing well, a recent case indicates there are other concerns over how the agency deals with allegations of serious misconduct against medical practitioners, and how it stores records internally.

In a recent decision in the ACT Civil and Administrative Tribunal, disciplinary proceedings were launched by AHPRA against Dr. Mohamed Helmy.

Three women came forward to make serious allegations of inappropriate sexual contact against Helmy. One of those women, identified in court proceedings as RJ, initially lodged a complaint with the Australian Federal Police (AFP). She alleged that Helmy had "touched her sexually whilst she was trying to pull away, and saying no".

The AFP notified AHPRA about the allegation. The medical board decided not to take any immediate action, but to commence an investigation. Two months later, the board decided to refer it back to police and took no further action, according to the tribunal decision, "as it was an alleged crime". But the AFP also closed the case, and had no further contact with the complainant.

It appears the outcome of this was that RJ's allegations were never tested in their entirety in the tribunal. The tribunal member notes that the woman "has not been contacted or asked to assist with this hearing".

"Without making any conclusions about what happened on 15 August, it seems that this matter fell between the two agencies," senior member Bryan Meagher wrote in his decision. "This is regrettable.

"It is to be hoped that RJ has been able to put it behind her and has not been adversely affected by the way the matter was handled or not handled."

Helmy was ultimately found to have engaged in unprofessional conduct. He was reprimanded and had several conditions placed on his registration.

A spokeswoman for AHPRA told BuzzFeed News that immediate action was taken in relation to Helmy, but acknowledged that it sought to make improvements to how it responded to allegations of sexual misconduct.

"We have an ongoing focus on improving how we engage with people who have made a notification, including extensive work in improving how we handle matters where allegations have been made about sexual misconduct," she said.

"All of these matters for doctors are now dealt with by a committee backed by investigators specially trained by Centres Against Sexual Assault (CASA). This also includes working closely with police forces in each jurisdiction."

It is clear there have been broader concerns raised about the agency for some time. The number of complaints against Australia's medical regulator has doubled in the last 12 months. Figures from the national health and privacy ombudsman reveal it received 181 complaints in the 2015–2016 year. This jumped to 363 in the 2016–2017 period, the highest number of complaints ever recorded since the agency was created.

A spokeswoman for AHPRA told BuzzFeed News that complaints about health practitioners had jumped by 14% in the last year, and there had been a 13.9% increase in notifications about registered health practitioners in the same period.

"In this context, it is not surprising that there has been an increase in complaints about how we work. We have an ongoing constructive relationship with the office of the National Health Practitioner Ombudsman and have a made a number of improvements in the light of their feedback," she said.

Contact Paul Farrell securely using the Signal messaging app on +61 457 262 172