For as long as I can remember, I’ve had a patch of skin on my lower back that looked odd. Only recently have I learned it’s a result of a rare type of blood cancer called mycosis fungoides, or MF.

While I’d had it checked out in the past, both the NHS and I had always misdiagnosed it as eczema or psoriasis. But this year I finally decided to push the matter with my new GP. She referred me to a private dermatologist, who took biopsies and quickly diagnosed me with MF.

It’s often missed; about 0.4 people per 100,000 per year are diagnosed with it, but more people may have it and be unaware of it, like I was. Despite being told I had cancer, I was glad to finally know what was up with my skin.

When the diagnosis was confirmed by a specialist, I said I was excited. They weren’t used to that reaction, but it all made sense when they learned that I am a programmer. Life presented me a problem, and I was looking forward to start working on it. Here are a few things I’ve learned so far:

1. Waiting is the hardest part, and Google can really fuck you over.

My initial diagnosis for MF went well, but I wasn’t actually told it was a form of cancer. It was only when I got home and searched for MF that I found out. The top link on Google was a sponsored advert, titled “Hey! Do you have a blood cancer?”; all I could mentally reply with was “Oh. I have a blood cancer”, followed by a sharp exhalation.

I called Macmillan, a leading cancer support charity in the UK, to see what was going to happen next. They didn’t know much about my particular type of cancer, but they were reassuringly calm, and did what they could to stop me freaking out. All they could really say was, “You’re going to see some specialists who will look into it, so wait it out for now.”

Knowing I had a type of cancer and not having a plan or a description of the severity was not pleasant. The five-year survival rate of my broader group of cancers (non-Hodgkin lymphoma) is 65-75%, but my actual survival chances are predicted to be much better than that. Research was not my friend in the worry stakes there, and I was very glad when specialists cleared that up for me. Perhaps I should have waited to talk to them before worrying.

2. It’s okay to retreat from your normal routine...

And I did; I simply didn’t have the mental capacity to deal with my standard day-to-day. I shied away from most social occasions, and even accidentally told my boss that none of my work seemed to matter any more. While I wouldn’t suggest doing that, he took it well. What did turn out to be a good idea, though, was talking to HR about my options moving forward.

I gave myself as much space as I could to process the diagnosis without entirely stopping work, and have been doing my job from the work sofa a lot more. After granting myself this space, I couldn’t help but feel like a strange, nonfunctioning blob stealing precious oxygen from my colleagues. In reality I was just a little quieter than usual, and spent a little more time picking the Galaxy Caramels out of the shared pot of chocolates the office has.

3. ...which is good, because your routine and plans are going out of the goddamned window.

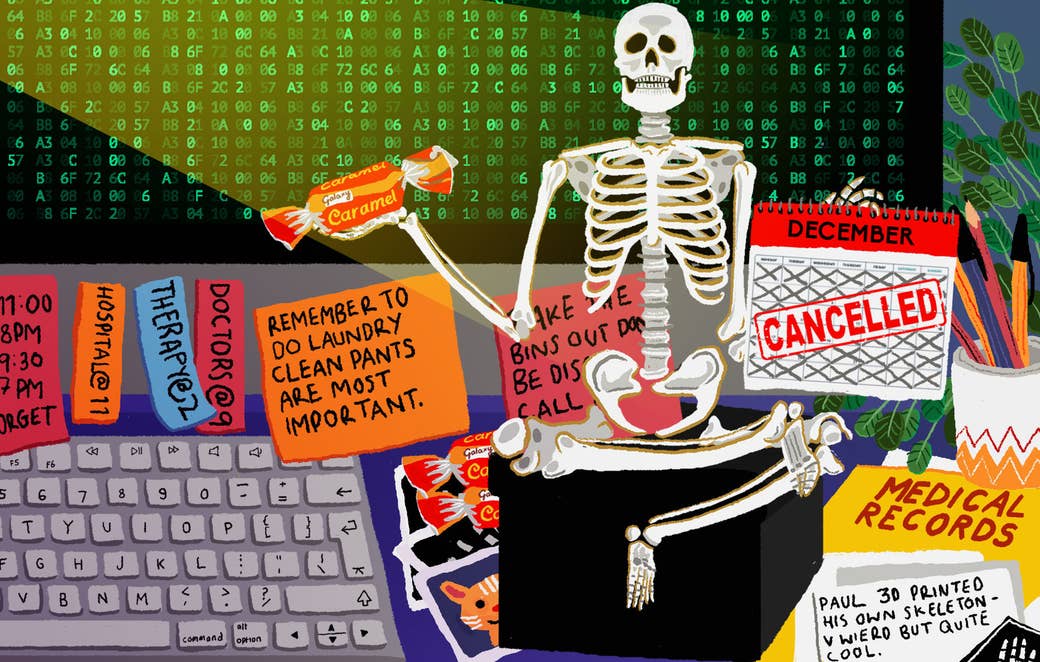

It’s difficult not to have control. I keep a tight schedule – everything is calendarised and planned to the minute. At any one time, I have at least five calendars on the go, tracking different interests and aspects of my life. And like anyone working in London, it’s pretty packed. I’ve long since been one of those awful people who has to organise drinks at least a month in advance.

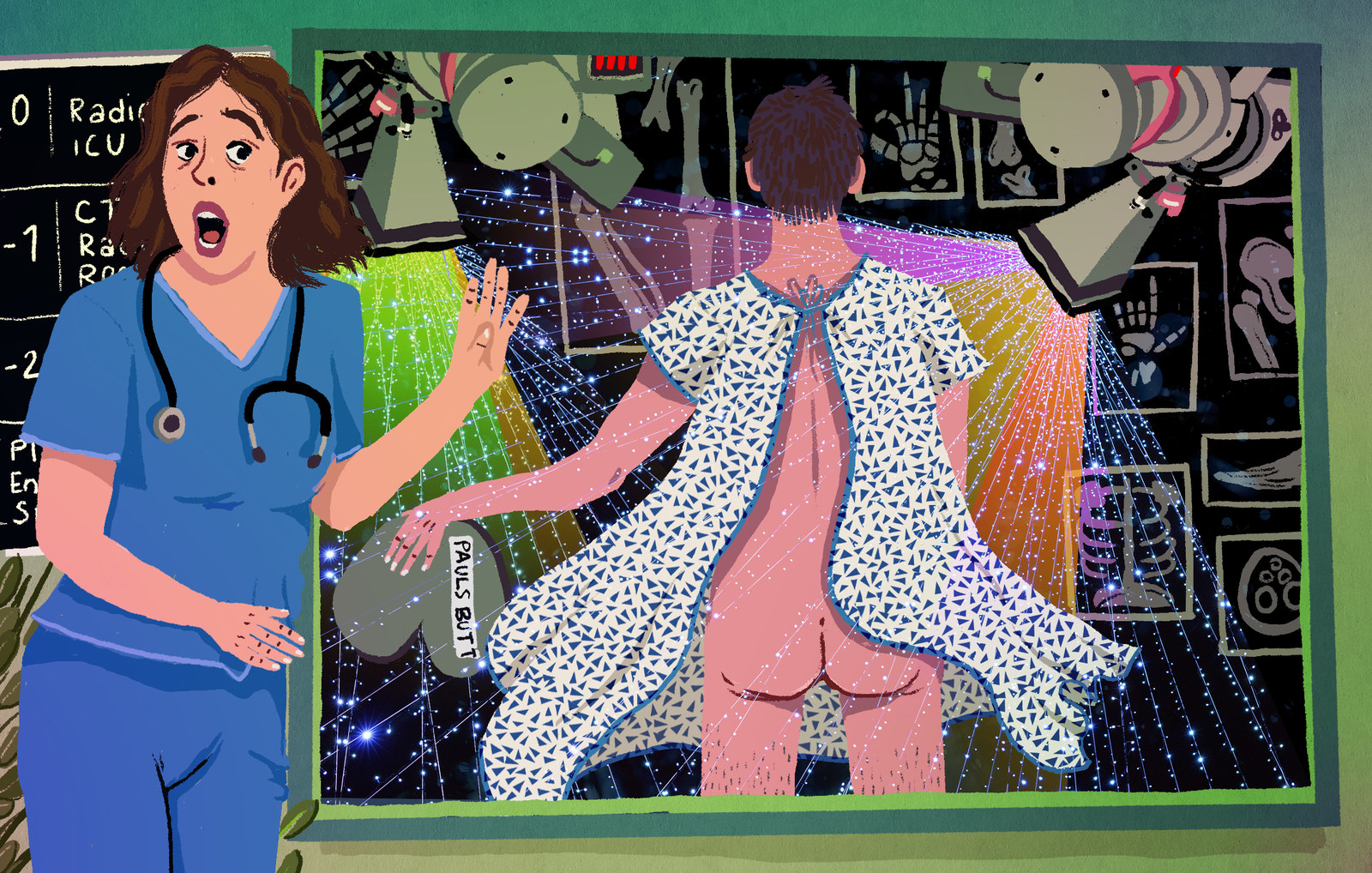

Getting a cancer diagnosis changes all that. Everything gets steamrollered over to accommodate hospital appointments, specialist checkups, treatments, and more – and in private healthcare, this moves very quickly. I went from initial diagnosis to having my butt under a radiotherapy machine in under eight weeks, with a flurry of appointments in between.

Your routine and stability get uprooted. Your holidays get cancelled, because there are now two hospital appointments that week. You miss drinks with your friends and have to fumble a weak excuse. It sucks.

4. Everyone copes differently. I printed my skeleton out.

One of my diagnostic scans was a full-body PET/CT scan. You know the kind – you’re put on a tray and pulled through a big magnetic doughnut. I had never had a scan like this before – they injected me with radioactive tracer from a lead-lined syringe, which I was absolutely certain would give me superpowers.

I’m a data dork, so I asked them if I could keep the medical imaging data – and to my surprise they happily handed it over! I loaded up the CD, transformed the DICOM data into a 3D model of my body, then extracted the skeleton from it by targeting the material density of bone.

Of course, I 3D-printed three copies of my skeleton out, at 10% scale. Reactions to this have been mixed. My counsellor thinks it's goddamned creepy. I think it’s totally rad. My radiologist was super impressed. It’s even been noted in my medical record that I’ve done this, which is the closest thing to a school “permanent record” that you get as an adult, so I’m quite proud of that.

It was a good distraction from having to actually absorb the news. I tend to cope through busywork, and this was good busywork, but now it’s complete, I’m focusing on counselling to actually deal with my grief.

5. I’m finding it useful to look on the bright side.

Yeah, I’m one of those eternal optimists. If you don’t laugh, you’ll cry, right? There are, when you look closely, a couple of bright sides. All my prescriptions are free for the rest of my life, for example! That’s going to save me so many £8.60s. Plus, how many people do YOU know who have a tiny copy of their actual skeleton printed out on their desk? Yeah, not many I bet.

Being an optimist can be hard work at times like this though; my first day back at work was tough. I’m usually so happy and upbeat in the office, but I felt fraudulent smiling back at people. It just wasn’t a very smiley week.

6. Private healthcare is fancy AF, but god bless the NHS.

Private hospitals really are something else. They’re more luxurious than most hotels I’ve stayed at. They have porters, people greet you by name, and there’s quilted loo roll. It’s really not what I’m used to, and I like to think I’m successfully lowering the tone.

The personal touch they like to add can be a little strange at times, though; my insurer called me one day, just to see how I was doing. All I could think to reply with was “Well, I’ve still got the cancer!”, which caused a super-awkward pause while they figured out how best to reply. I am great at phone calls.

It’s strange how little I thought about health insurance until I came to lean on it. It’s now something I would go out of my way to keep: personal case managers, dedicated teams, the speed at which you’re seen – it all helps reduce stress. I was even given complimentary access to some in-personal counselling after my radiotherapy, which I’m taking full advantage of. I haven’t had access to talking therapy for ages, so they’re getting an earful of entirely unrelated stuff, but they don’t seem to mind.

However, none of this works without the NHS – it's responsible for a large part of the funding my specialists receive to conduct crucial research.

7. The reactions of people close to you are heartbreaking.

There’s something about other people’s reactions that are so much more real than your own. After my diagnosis was confirmed by a specialist, it was my girlfriend quietly holding back tears on the train home that hit me really hard, rather than the diagnosis itself.

This has been a recurring theme; seeing your health and wellbeing affect other people who care deeply about you adds this whole layer of “damn, this is serious, and they really love me”. As someone who barely loves themselves 99% of the time, these reactions strike right to my heart.

I also have to be mindful of those around me – this is way more than my partner swiped right for on Tinder a few months back, for example; I’m careful not to overwhelm her with the burden of emotionally managing me on top of everything else.

8. Figuring out how to disclose appropriately is difficult.

A big part of the reason for publishing this is so my friends can read it and understand why I’ve been so flaky recently. I haven’t told many people yet, for various reasons: It might just seem irrelevant to the context, their reactions can be upsetting, or you just don’t want to ruin their morning by telling them. After all, they might already have had a horrible experience with cancer, and you don’t want to cause them grief through recollection.

It makes for a tricky balancing act. When those around you notice you’re a little down in the dumps, it’s only natural for them to ask what’s up, and you wonder if it’s appropriate to actually tell them. But sometimes, when you do, lighter replies like “Well, that’s a shitter, want some wine?” can be the best.

On the other hand, when you want to tell someone to back down or be nicer, playing the cancer card could really make you look like a dick, as it’s not a proportional response. This makes disclosing difficult, because a lot of the time it would be really disruptive to do so, even when you do need some space.

9. I don’t have superpowers after radiotherapy – I’m just tired.

Being tired all the time is a bullshit superpower, but I’m told it will pass in a few weeks time as my body heals up the area.

The treatments weren’t quite what I expected – for example, I thought radiotherapy treatment would take ages, but my initial sessions have only taken about five minutes each. It took longer to measure and plan the treatment area than it did to have the actual treatment! Together with the PET/CT scan, the radiotherapy gave me a valid excuse not to sit next to old people or babies on the train for two whole days, since I might have irradiated them a little bit. The perks just keep coming!

They have to cut out a piece of lead to protect the rest of your body from the radiation, so now, somewhere in London, is a lead shield in the shape of my butt. They wouldn’t let me keep it. I did ask.

10. Life goes on around you, and it can make you feel very small.

I’m a doer – I like to get things done and make progress whenever I can. Stepping back from life has been tough; you don’t want to feel like you’re letting everyone down, even though you know they’d understand.

I tend to go a little bit quiet on social media when at appointments, since they all seem to be in lead-shielded basements where I don’t get a phone signal. Twice now, I’ve had DMs from people saying, “You’re shitposting on Twitter a lot less than usual, are you OK?” I guess that sometimes you want a social media and work flag that says “Yo, things are really rough for me right now, please be nice to me”, but as my friend Holly points out, that just isn’t a thing.

11. A cancer diagnosis can require a lot of mental capacity, sometimes without warning.

Imagine a brain diagram of normal stuff. Eat, sleep, job, friends, etc. That’s all suddenly dwarfed by “WOMP! CANCER!” and everything else takes a giant hit as it’s swept aside.

The amount of headspace it requires is always in flux too. Some days, it’ll be absolutely fine, until without warning you find yourself staring vacantly at the potato mashers in John Lewis and the staff have to ask you if you need any help.

I’ve had to rely on a lot of reminders and alarms recently just to ensure that the basics get done and nothing backs up too much. Doing the laundry, taking your medication, putting the bins out, remembering to do the washing up – I forgot them all at least once, and I had to bite my pride a little bit when setting up reminders for such basic things.

12. My relationship with my body has changed.

I only really become aware of my health recently – it took until I was 27 to begin to get my act together as an adult somewhat. I have started to take the time to actually go to the dentist, get GP checkups, and realise that I am not indestructible.

As a bonus, I’m really not afraid of showing people my butt any more; so many different medical professionals have seen it at this point. Luckily, I have an excellent bottom, but it still takes a bit of getting used to in order to be casual about it.

13. At the end of the day, I’m very lucky.

Yes, I have incurable cancer and an unattractive patch of skin, but I’m still here and will continue to be. I am very aware that there are people going through so much worse than I am, and sitting in the waiting room of the cancer wing at Guy's really highlights the mix of brilliant people this bastard of a condition affects.

For quite some time I felt like a fraud. While my cancer is incurable, it’s very likely that I’ll die of something else first. Yes, I have to manage it for the rest of my life, but this is a very low-risk type of cancer, which makes me feel a like a fraud compared to the majority of scarier cancers. The treatments are not intensive – there probably won’t be any hair loss, and life will largely go on as normal.

Replying to “How are you doing?” with “Surviving! You?”, “Getting there!”, or “Grurrrrghhh” is just honest, helpful, and typically British lift chat. I’ve since started smiling back at people again, and while sometimes it cracks, I’m getting there.