Poofters. Benders. Shirtlifters. Bumboys. Lezzies. This was how British tabloid headlines referred to gay men and lesbians in the 1980s — an echo of the taunts heard on the street before a beating. The stories beneath would expand on the pejoratives, justifying them with news of “sick”, “evil”, “predatory” gays — all arising from a presumption: that readers would agree.

It came at the worst time. After the burgeoning liberation movement and the shirts-off, arms-up disco era, gay men started dying in the hundreds, then thousands.

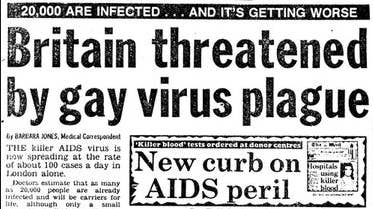

As AIDS hit in the early 1980s, Fleet Street, then the home of Britain’s newspaper industry, responded by blaming gay people for their own deaths; lying about the causes of the disease; calling for a return to the closet, to abstinence, and even to prison. Later, when the Conservative government gagged teachers from discussing homosexuality, many newspapers roared in approval.

But there was one gay man who decided to fight back, with words of his own.

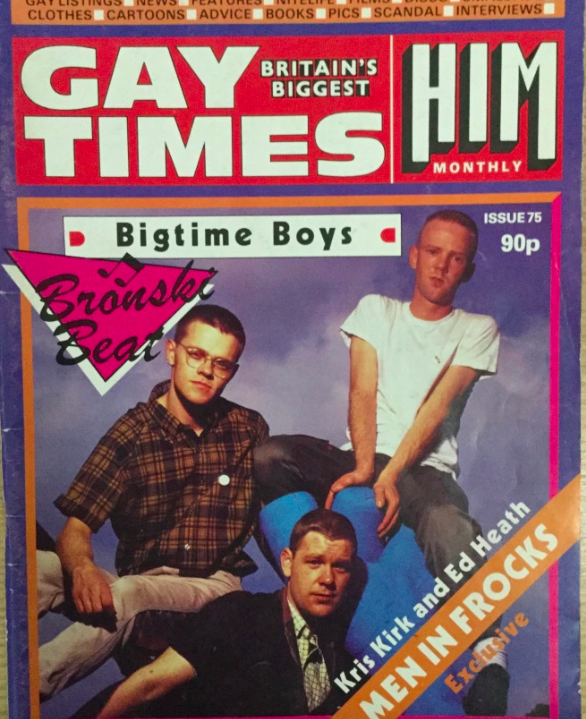

From 1983, Terry Sanderson began to document newspapers’ slurs against the community in a column for Gay Times magazine (then the most important gay publication) called “Media Watch”. He dissected the worst — the myths, the stereotyping, the outing of members of the public — and responded to the onslaught with wit and fury, all while providing LGBT people with something invaluable: a voice.

He accused tabloids of turning its coverage of gay people into a “blood sport” — the difference being that “with gay-baiting nobody seems concerned about the barbaric cruelty of it all.” He mocked the most what-the-fuck ludicrous coverage — the Daily Star’s assertion that “the Rottweiler is the gay community’s favourite pet” or the Sun’s headline: “Gays Axe Christmas”. And he lambasted his own community, too — if deemed to betray the cause.

On one occasion, Kenneth Williams, the famously self-hating gay actor, told an interviewer, “Anybody who pretends that two men can live together happily like man and wife is talking a load of rubbish.” Sanderson responded in “Media Watch”: “At the beginning of the interview, Mr Williams proclaims, ‘I am a cult’, although I’m not sure he’s spelt it right.”

The column was only supposed to be a one-off. But he didn’t stop for 25 years, outlasting all the columnists who were frothing when he first started.

He also secured a first: a historic win, holding a newspaper to account for its smears against gay people.

Earlier this year, while on a break from cancer treatment, Sanderson decided to unearth all of his old columns and publish the lot online. The resulting website, GTMediaWatch.org, now provides a unique insight into the period and comprehensive evidence of what the media, politicians, and public figures did during the most pivotal fights in LGBT history: the AIDS crisis, Section 28, the age of consent, civil partnerships, fostering, and adoption.

It’s all there, much of it in newspapers that are not the most obvious culprits.

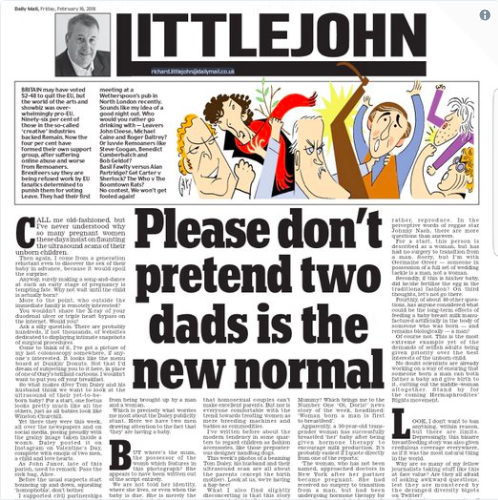

But the timing bites. As many British papers shift, now encircling transgender people with repurposed taunts, Sanderson’s decades-old polemics about the media’s treatment of “dykes” and “buggers”, and how they pose a threat to children/decency/society, foreshadowed it all.

His column also serves as a warning. This, it says, is where words lead. LGBT people are still bloodied on the street, still defiled by reporters, and now pursued on social media. Fractured, furious Britain poses fresh threats to the marginalised. Sanderson’s words call out to editors: You have a choice.

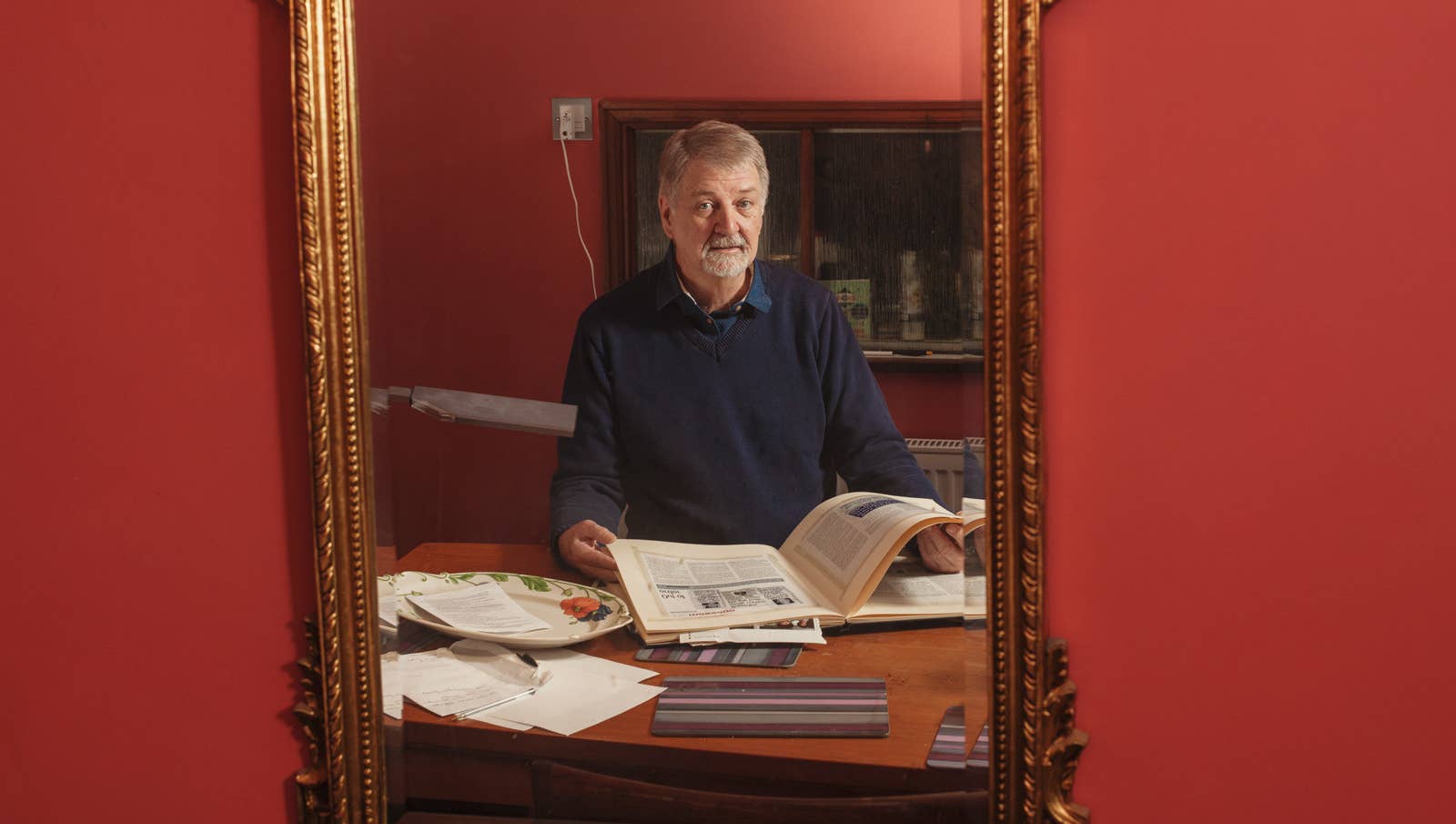

BuzzFeed News visited him at his home in Ealing, west London, to discover why he stood up to Fleet Street for so long — and what it did to him.

Nothing, it transpires, is what you might expect.

Terry Sanderson lives with his husband, Keith, in the comfy, velvety home they have shared for 35 years. Today Keith pokes his head into the living room to offer tea and hot-cross buns. On his return a few minutes later, Sanderson takes two bites and begins to talk.

He was born in 1946 in Maltby, a Yorkshire mining town, and bred among the community of pit workers, the very people who, as he was later writing his column, would give Margaret Thatcher the middle finger. “Nobody messed with them,” he says.

Sanderson’s voice is soft and rich, his accent rippled with South Yorkshire inflections. Despite the militancy of his writing and the gentility of his manner, there is something of the corduroy about him: sturdy, comfortable, sensible.

“It was always obvious I was gay,” he says of his childhood among the miners. “There was no escaping it — camp as arseholes from day one. But it wasn’t talked about.”

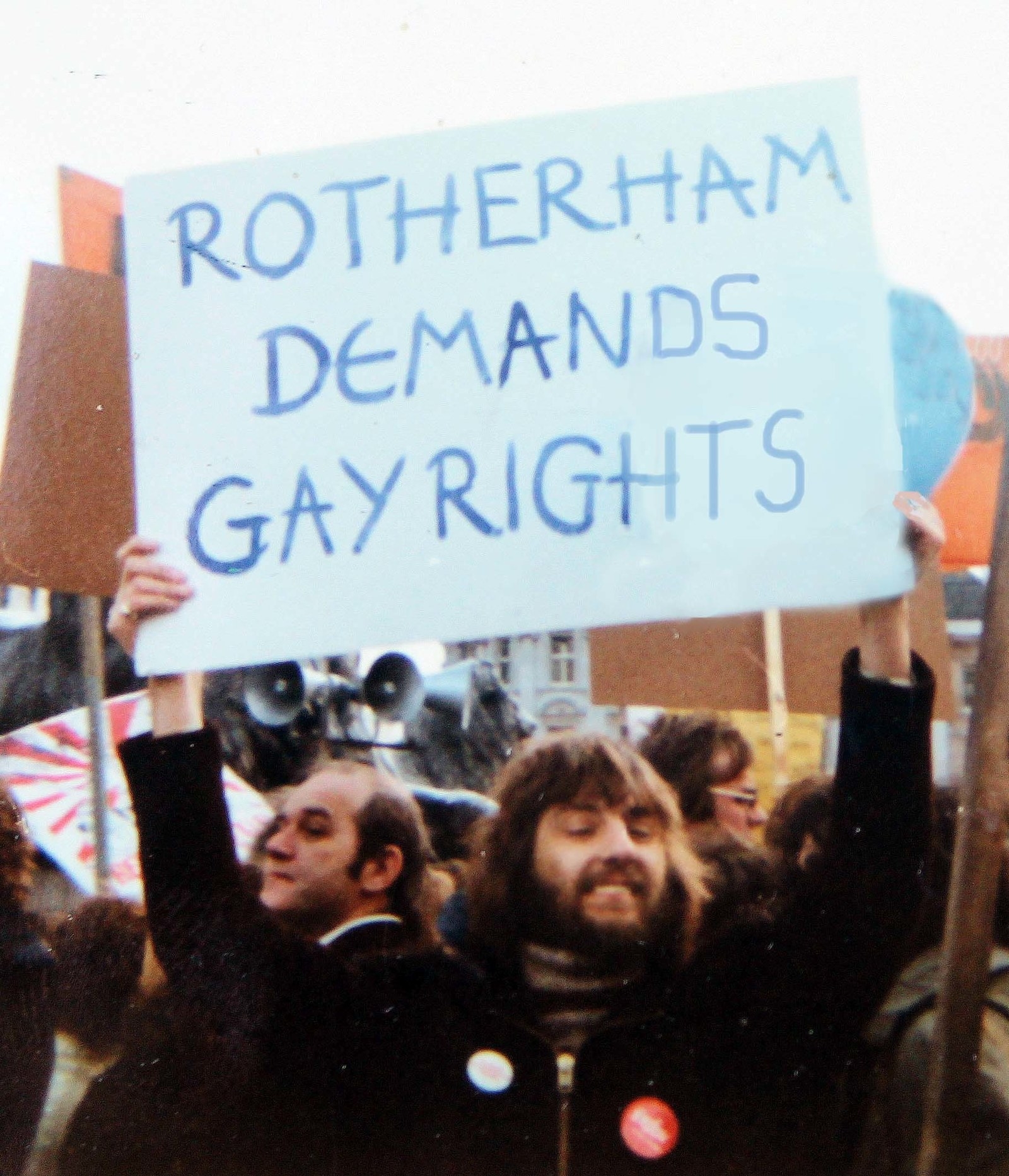

As adolescence became adulthood, isolation engulfed Sanderson. Where, he wondered, were the people like him? It was the 1970s, and the Gay Liberation Front marching through London was far from permeating small-town Yorkshire.

Sanderson decided to do something about it. While working in a photographer’s shop in Rotherham, he founded a local, Yorkshire-based branch of the Campaign for Homosexual Equality, one of the early and rather polite gay groups. The phone started to ring. “I realised there are an awful lot of people isolated and alone and frightened,” he says. But there was an even more basic revelation that would awaken Sanderson. “There were gay people all over the place!’” he exclaims. “Over Maltby, all over Rotherham, everywhere!”

From this, his consciousness grew, fuelling everything that was to come. “I started to read Gay News,” he says, referring to the publication that would become Gay Times, “and see [from its reporting] all these discriminations happening: gay people getting kicked out of their jobs, parents rejecting them."

His group became more political, dividing its members. Many lived with so much fear as to wish only to remain invisible. “Don’t draw attention” was their attitude, he says.

But instead of this deterring him, it flicked a switch. “I started to think, We want our place; why shouldn’t we have it? It made me look again at the way we were being treated in the press and think, No. You’re wrong. Stop it.”

By now, 1983, he was living in London with Keith and dabbling in journalism, just as the newspapers’ attacks mounted. “I was beginning to see all this stuff and thinking, Where is all this coming from? And, more to the point, where is it going?” It was the year that the AIDS virus was isolated.

Sanderson wrote a piece for the magazine about the media’s coverage of gay people, and impressed, the editor asked him to turn it into a monthly column. He had no idea that for the next quarter of a century it would fall to him to document the anti-gay distortions written by those whose job it was to reveal the truth.

To read any of the early columns is to be jolted by the sheer volume of attacks. In a typical example from 1985, Sanderson is left returning fire on one anti-gay piece after the other, all drawn from a single month. The first, a Sunday People spread under the headline “Ban the Panto Fairies”, saw the comedian Bernard Manning arguing that gay actors should not be allowed on “television, on stage, in clubs or pubs” in order that they don’t “corrupt the children”.

“This is rich,” wrote Sanderson, “coming from someone who for years has made a living out of uttering the most filthy racist abuse imaginable.”

Next was a Spectator columnist who had written that “extreme promiscuity has led to the Aids epidemic… a disease caught by men who bugger and are buggered by dozens or even hundreds of other men every year."

Much as others might be tempted to suggest a note of envy in the prose, such words, wrote Sanderson, didn’t even warrant their own takedown for one simple reason: They were copied. “Almost word-for-word from a column in the New York Post”.

So Sanderson jibed: “Not able to write his own bigoted column he plagiarises other people’s.”

It wasn’t just the national newspapers. In the same column, Sanderson selected a delightful mezze of local paper bigotry. “Gays are EVIL” was the headline in a recent edition of the Bromley Leader. The Plymouth Evening Herald described a mere advert for a gay club as “an offensive gay club poster”. Meanwhile, the Solihull Daily Times blared in a headline: “Row over poofs and queers”.

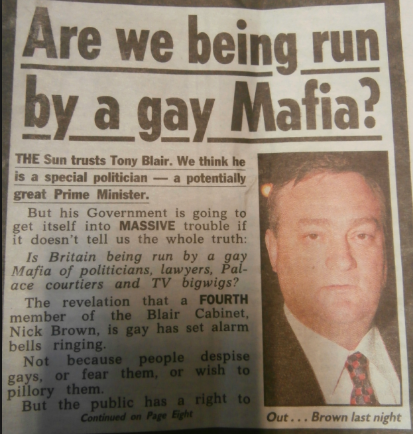

In the same column, he reported that the Sun, Britain’s bestselling newspaper, had “negative gay stories almost every day for the past few weeks”. In one, the paper branded a council leader “barmy” for campaigning for black and gay people to be protected from murder. “Does Mr Murdoch’s excuse-for-a-newspaper applaud mindless thuggery then?” Sanderson asked. “It seems so.”

His column warned that “these are crude and extreme attacks but they are becoming more frequent,” with a call to arms that would be repeated often in the forthcoming years. “It’s up to us all to ensure we don’t let these slanders go unchallenged,” he wrote, encouraging readers to complain to the editors as it takes “a long time to counter hatred and persecution once it takes hold.”

These attacks, in the press and in the street, came at a time when there were no legal protections for LGBT people: the law did not recognise anti-gay hate crimes, you could be fired or evicted because of your sexuality, and the age of consent was 21 for gay men.

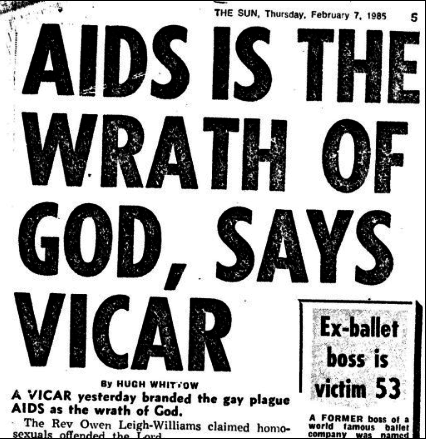

But it was the AIDS crisis, rising through the 1980s, that brought Sanderson’s column into terrifying focus.

Shortly after the Sun’s near-daily anti-gay coverage, The Times declared its official position in a leader editorial: “Many members of the public are tempted to see in AIDS some sort of retribution for a questionable style of life.”

“It’s all our fault, is it?” fumed Sanderson in “Media Watch” before quoting a headline in the same edition of the paper: “Is it wise to share a lavatory with a homosexual?”

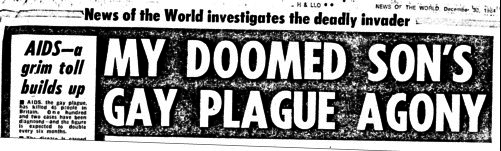

But the Times, in its tenor, was among friends. “The News of the World carried ‘gay plague’ headlines in three consecutive issues,” wrote Sanderson, detailing each one: “Victims of gay plague long to die”; “My doomed son’s gay plague agony”; “Art genius destroyed by gay killer bug”.

All of which, he wrote, reeked of a “sick self-congratulation” redolent of a self-soothing lie: “It can’t happen to us because we’re straight.”

When the Sun then called gay men “walking time bombs” with the “killer disease AIDS” who are a “menace to all society”, Sanderson wrote to the editor, Kelvin MacKenzie, asking “whether he was prepared to take responsibility for acts of violence which might be incited against gay men by this highly provocative editorial”. This wasn’t hypothetical: people living with AIDS were having petrol bombs thrown through their letterboxes.

MacKenzie’s reply was reported in Media Watch: “I do not accept that our editorial did any more than urge all homosexuals, in the interests of the entire community, to think twice before giving blood.” This did little to dissuade Sanderson from referring to the staff at the tabloid as “Suns-of-bitches”.

Even when the evidence was clear that heterosexuals also had HIV, the Sun, wrote Sanderson, “still insisted that AIDS sufferers were ‘gay plague victims’” and merrily printed headlines unencumbered by facts: “Beer mugs may spread the disease”.

Broadsheet newspapers did not escape the glare of “Media Watch”, either. The Telegraph published a column arguing that it wasn’t scapegoating to accuse gay men of spreading AIDS because “male homosexuals are undoubtedly responsible”.

Under this quote, Sanderson wrote a multipoint plan of action for any reader wanting to fight the bombardment. He suggested blitzing editors with letters and phone calls to insist on responsible reporting; writing to MPs and the National Union of Journalists; telling friends and family the truth about the virus — anything to counter the lies.

Seeping out of every sentence was not so much Sanderson’s fury as his terror: Friends were dying, gay men were being attacked, but newspapers kept going.

“It became very intense,” he says now, looking away. “The opposition and hostility was day in, day out. ‘Severe’ is not the word. It was horrendously hostile. I thought if this goes on much longer, there’s going to be some kind of terrible reaction.”

Two years later, in 1987, “Media Watch” revealed how much the tabloids had changed. “Perverts Are to Blame for the Killer Plague” was the Sun’s headline on Dec. 12, under which the accompanying leader article asked: “Why do homosexuals continue to share each other’s beds? ... Their defiling the act of love is not only unnatural but in today’s Aids-hit world it is LETHAL.”

This was mild compared with the Daily Express, which quoted — without comment — one of its readers: “The homosexuals who have brought this plague upon us should be locked up ... Burning is too good for them. Bury them in a pit and pour on quick lime.”

Sanderson feared that homosexuality itself would be recriminalised — not a stretch when the Sun had suggested locking gay people up, since they were, apparently, an “evil threat to society”. And so, Sanderson wrote that, with 4 million readers and other papers emulating its vitriol in a fight for circulation, “The Sun is a serious threat not only to the quality of our lives but now to our very existence.”

He remembers how frightening it was, this malignant wallpaper plastering the country — in part because newspapers were much more powerful and widely read than today. “They were so insistent: Everything about gay life was negative,” he says. At times even other mainstream news outlets cried out. The Guardian warned in 1987 that such coverage represented a “sustained attempt to resurrect the mob”.

Many gay people Sanderson knew at the time simply refused to look at newspapers, “pretending they didn’t exist”. But all the while, he says, much of Fleet Street was “inciting other people to violence” against lesbians and gay men. He feared worsening bloodshed. In a six-month period between late 1989 and early 1990, there were four anti-gay murders just in West London where he lived. It took until 2006 for the first person to be found guilty of such a crime.

“I used to make the point to journalists all the time — words can lead to actions, and the violence of your words can provoke people into feeling justified in actually violating real people in the street,” he says. “They never accepted that was the case.”

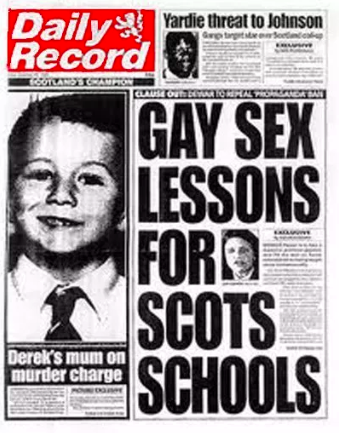

In 1988, when Section 28, the new law preventing mention of homosexuality in schools, was in the news, Sanderson again used “Media Watch” to galvanise the community: “Now we must be ready to fight it every step of the way.” The legislation had been born of a media-lit moral panic over books informing children that some people have two mothers.

Once alight, the editorialising became ever more puerile. When activists, for example, “threatened” members of the House of Lords over the bill, the Sun responded: “It could have been worse for their Lordships. The poofters could have threatened to KISS them instead.” (Anti-gay language was often helpfully capitalised.) The People wrote of the same alleged threats: “Time was when we thought hell had no fury like a woman scorned. That’s nothing compared to a poofter peeved.”

Even the insults were inexpertly delivered.

In many of the columns, Sanderson’s tone was so confrontational as to feel as if it could have been written last week; not because of today’s omnipresent fury but because his fuck-you stance was so distinct from the self-loathing that rendered many apologetically congenial at the time.

“I got into that mindset quite deliberately,” he says. “I thought, ‘No, I’m not going to apologise, I’m going to tell ’em. I had to — on behalf of other people who were still frightened and cowed by this aggression from the tabloids. I had to say, ‘No, you can stand up and say fuck off.”

At other points, however, he simply sounded arch, as if sighing while inspecting his nails. When the Evening Standard wailed about a “Storm over gay sex books for 2 year olds” (also during the Section 28 furore), Sanderson countered, “Presumably these books are available in a school for infant prodigies who can read at the age of two?”

And when EastEnders became, in 1989, the first British soap opera to show a gay kiss, Sanderson quoted the Sun: “The homosexual love scene between yuppie poofs was screened in the early evening when millions of children were watching” before puncturing the hypocrisy therein: “just in case any Sun-reading kiddie missed it, the shocking peck was photographically reproduced for their edification”.

The Guardian, which later claimed to be “the world’s leading liberal voice”, was not without fault, either, Sanderson says. He accuses the outlet of “giving a voice to people who should never have one in a paper like that, simply because they felt they should have balance.” Sometimes it was worse than that. “Media Watch” highlighted the reporting of a vicar who had been caught cottaging, entrapped in a public toilet by a policeman, but rather than criticise the police, the Guardian published the defendant’s home address. At one point, its coverage led to gay protesters occupying the newspaper’s offices.

(Much later, in 2004 and 2013, further protests would be staged there, but over anti-trans columns. These contained phrases such as “man in a dress”, “dicks in chicks’ clothing”, “shemales”, “trannies,” and a warning to trans people: “You really won’t like us when we’re angry.”)

Sanderson’s column also mocked newspapers for what they didn’t say. In 1987, When James Baldwin, one of the most important voices of the 20th century, died, “Media Watch” scoffed: “The two subjects on which James Baldwin wrote most passionately were racism and homosexuality. His obituary in The Independent managed to fill three long columns without once mentioning the writer’s gayness.” This omission was an “affront to his memory and to the dignity of the whole gay community”.

Similarly, in 1984, when Gay’s the Word bookshop was raided by Customs and Excise officers, with 144 titles confiscated on the grounds of obscenity — books by such apparent pornographers as Jean-Paul Sartre and Gore Vidal — the column fumed: “No mention in the national newspapers”.

In this, “Media Watch” captured a cold truth: Newspapers were uninterested in the harm committed against gay people because they were too busy committing it themselves.

On occasion, however, the papers would report hate crimes — in order to cheer. When homophobes vandalised a flowerbed that had been planted in Manchester to celebrate Pride, the Sun’s “predictably jeering reaction”, wrote Sanderson, was: “Anti-gay gang wipe out pansies!”

But he didn’t only use his column to fight back. He took action. He went to the Press Council — or “invertebrate Press Council,” as he called them — the body that was supposed to regulate newspapers, and made complaint after complaint after complaint. All of which were, for years, rejected on the grounds of press freedom (“We must be free to call them benders!” was the argument).

But then, in late 1989, a new, liberal man took charge of the council: Sir Louis Blom-Cooper.

“I went to see him,” says Sanderson before lowering his voice conspiratorially. “He said, ‘keep making complaints and it [a successful ruling] might happen.’”

So in early 1990, Sanderson rounded up some recent columns by Gary Bushell, a columnist for the Sun notorious for his anti-gay abuse, and made a complaint to the council. These columns contained such refined terminology as “woofter” and “poof”, attacks on television programmes that “promote homosexuality,” and lines such as, “It must be true what they say about nobody being all bad … even Stalin banned poofs!”

Months later, and for the first time in its history, the Press Council upheld a complaint against a newspaper for using anti-gay language. Sanderson had won.

In its ruling, the council said: “The words ‘poof’ and ‘poofter’… were so offensive to male homosexuals as not to be a matter of taste or opinion” and therefore should only be printed where “necessary for the purpose of proper understanding of the item in which the offensive words appear”.

Sanderson remembers the day the adjudication arrived in the post.

“I jumped in the air,” he says, beaming.

The joy did not last. Along with newspapers bristling with indignity for being told off, the Sun itself responded with the headline: “You Can’t Call ’em Poofers” under which the paper raged against the council for its “lordly manner over language” while accusing gay people of “appropriating” the word “gay” from its dictionary definition.

But the backlash eventually ebbed, says Sanderson, as newspapers began to realise “which way the wind was blowing”. Their readers were changing before they were.

Sanderson’s complaints were not only about journalists’ offensive language, it was also their actions. “Every week in the News of the World there’d be some vicar or actor or someone just getting on with their life and they’d be outed,” says Sanderson. Some of whom had been caught cottaging, thereby revealing how co-joined the anti-gay forces were: “It was the police who told the press.”

One of the most prominent figures to be outed by the press was the chat show host Russell Harty. “He never really recovered,” says Sanderson. But there were also members of the public; in one instance a surgeon was exposed for his HIV status. “He was hounded out of his job because of what the papers were saying, frightening people. I just thought, Why don’t they say that if you follow the correct procedures, nobody is at risk?”

Some public figures fought back, playing the papers at their own game. When the News of the World was tipped off about the sexuality of Gorden Kaye, the beloved ‘Allo ‘Allo actor “went to the Mirror [its rival],” who were “much more sympathetic” and who then published it on Saturday, ruining the Sunday paper's exclusive.

The outings continued. “It never occurred to them that they were harming people,” he says.

But what about Sanderson? What effect did reading and responding to all this, week in, week out, for decades have on him?

He looks straight ahead. “I was outraged and angry about all of it, but I didn’t let it penetrate,” he says flatly, in almost mechanical defiance, before explaining what distinguished him from many during this period who were simply trying to cope — childhood rejection bleeding, often literally, into adult brutality.

“As a child, I always felt safe in the bosom of my family,” he says, a rarity for LGBT people then, if not now. His relationship built upon this. “If it hadn’t been for Keith, it might have really got to me. He’s always looked after me and made sure no catastrophe overtook me.” Sanderson pauses for a moment. “Although he couldn’t protect me from cancer.”

From the late 1990s, they both worked for the National Secular Society, Sanderson as its president before Keith (whose surname is Porteous-Wood) took over the same role in 2017. Sanderson eked out his modest fee for the column through other journalism and by working as a psychiatric nurse.

And then, a few years ago, the call came: A new editor had decided to ax the column. Sanderson is sanguine about this. “I knew it would have to come one day,” he says. “The magazine was losing money; they had to regenerate it, make it more lifestyle-y.”

Now retired, and no longer scanning the papers every day, he remains aware of what is happening in the media, and it worries him: the new campaign, this time against trans people.

“The whole thing is starting again,” he says. “They seem to need a scapegoat, someone to project all societal discomfort onto. People are fed up with the political system and somebody’s got to pay. It’s usually a minority that can’t hit back.”

IPSO, one of today’s press regulators, is currently conducting a review of newspaper reporting on trans issues. The Times is meanwhile fighting an employment tribunal against a former editor suing for anti-trans bullying and discrimination who argues that the paper’s coverage is itself evidence of this. Many trans people are frightened by the coverage — unable to look, some unable to leave the house. Christine Burns, one of the pioneers of the community who helped create the Gender Recognition Act, told staff at the Guardian last week of the effect anti-trans reporting was having: “I’m scared to death.”

One of the problems regarding how journalists approach the trans community, says Sanderson, is “people don’t understand it, and that was a very similar thing with the early days of gay visibility. It was new to them, and something they thought only existed in a tiny, tiny minority living somewhere not here.”

Sanderson seems, at 73, disconnected at times from the horrors he documented — perhaps necessarily so — but at others, certain memories shake him: the fear-mongering during the AIDS crisis in particular. “Somebody should have been punished,” he says, “for the way they misinformed people to create panic.” As for Kelvin MacKenzie, the then-editor of the Sun? “I’ll never forgive him,” he says.

We change the subject to his recent treatment for cancer. What’s the prognosis now? “Hopefully gone,” he says in a touch-wood voice. “But I’ve got to see [the doctor] again next month for my three-monthly checkup.” As he continues talking about the illness, unspoken parallels begin to resonate, crackling between the malignancy in the body and the stoked malevolence outside.

“It’s always in the back of your mind,” he says, his voice dropping to a hush. “It’s always a possibility that it’s lurking somewhere. Waiting.”

BuzzFeed News approached the Sun for comment. The newspaper declined.