Edwin J. Bernard lives by the sea, up four flights of stairs, in a small, bright attic overlooking the English Channel. As seagulls squawk through the open window and sea air billows in, a tiny picture sits near the windowsill. It is Bernard in 1995 with his arm round another man. His name was Craig. He didn’t make it.

Bernard was not supposed to either. He knew he would not. He was told he would not. But here he sits 21 years later, fingers interlocked, talking rapidly, sometimes veering away from the most unbearable memories, sometimes sinking into them – still, decades later, trying to decipher shapes in an abyss. He survived a war no one won.

Freakish luck saved him. But there is something else, other than a medical revolution that appeared just in time. It takes hours to find out what it is, when the last thing he says loops round to the very first: There is, he says, a box in the storage space above his head that he has never opened. He cannot. What’s in the box is the other thing that saved him – and he can’t bear it.

Bernard gazes over at the photo. “I don’t even know if I would recognise the me from ’95,” he says. “My sense of who I am, my purpose in life. Twenty years on I think, Who was that person?”

He looks ahead again, out through the window to a present, a year, so unforeseen as to have once seemed preposterous.

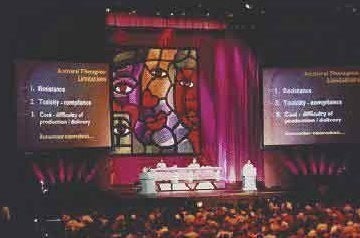

Twenty years ago, in the summer of 1996, hope surfaced. After 15 years of horror, with AIDS decimating communities, families, whole continents, a raft of startling data was presented at the 11th International AIDS Conference in Vancouver.

It revealed the extraordinary power of the new antiretroviral drugs, called protease inhibitors, which, when used together, formed what became known as combination therapy (or HAART – highly active antiretroviral therapy) – a cocktail of medication that disabled the HIV virus, cutting off its life cycle.

Although not a cure, by suppressing the virus, the drugs could change the course of an epidemic and with it the face of the cruellest of diseases. People would be saved. And people were.

It just wasn’t that simple.

This is the story of three people who prepared for an early death that never came. What they experienced – rising from their sickbeds on three different continents, the end swapped for a beginning – happened everywhere the drugs were made available. Death rates plummeted. The phenomenon of this second burst of life was given a name: the Lazarus effect, after Saint Lazarus, the biblical figure resurrected by Jesus four days after his death.

But even that story was not simple: News of the apparent miracle accelerated plans to crucify the man responsible – and kill the man he saved.

Life after near death, it transpires, changes everything.

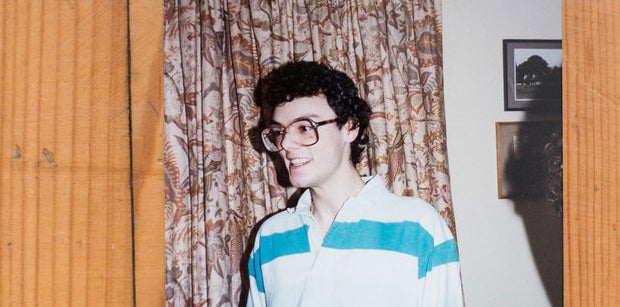

It was 1988 when a doctor told Edwin J. Bernard the news.

“He said, ‘You’re right; you’ve got HIV,’” says Bernard. “I didn’t get pre- or post-test counselling.” He was 25, from a Jewish family in Blackpool, England. There was no treatment. Instead, adverts on British television simply told people not to “die of ignorance”; a menacing boom illustrated by a falling tombstone. Thousands – especially gay men – already had.

“I went into functional denial,” says Bernard. “I also had a bit of a nervous breakdown.” Some who had been diagnosed jumped off buildings. Others had their houses firebombed.

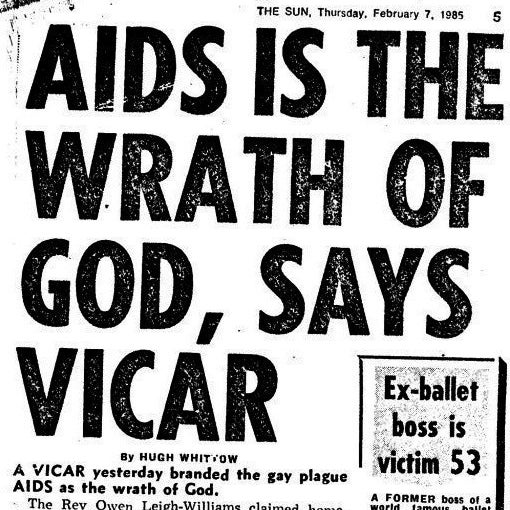

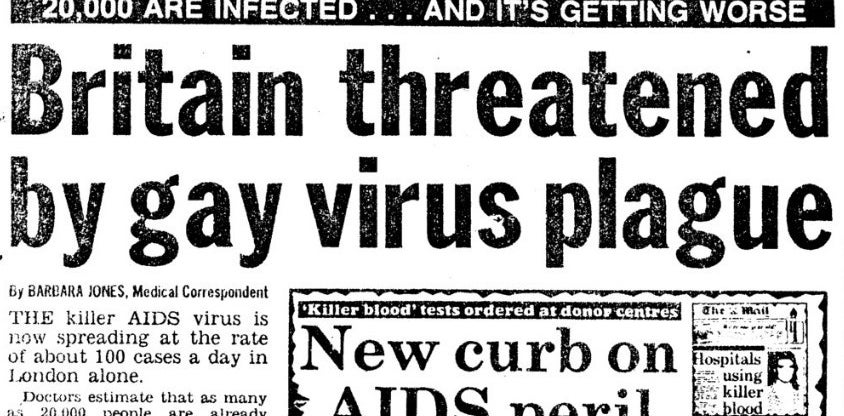

Graffiti shown on EastEnders – the first British soap opera to feature an HIV-positive character – captured a slice of public attitudes: “AIDS SCUM”. Newspapers said it was the fault of the afflicted. Christian leaders said it was God’s work – punishment. Mothers discovered that their sons were gay at the funeral. Surviving partners were locked out of wakes, wills, and homes.

Bernard found a sympathetic family doctor in Finsbury Park, north London, where he was living. He told no one else.

“In the '80s the stigma was overwhelming,” he says. “You were walking in this fog of it.” The only thing the doctor could give Bernard was advice: “Just take care of yourself.” He tried as hard as he could.

“Part of my brain was thinking, I’m gonna die, I’m gonna die, and the other part was, Don’t be ridiculous; it can’t happen to you.”

“Part of my brain was thinking, I’m gonna die, I’m gonna die, and the other part was, Don’t be ridiculous; it can’t happen to you.”

Even a couple of years later when another doctor signed a form saying Bernard had less than six months to live, so that he could apply for benefits – disability living allowance – Bernard refused to accept that a ceiling was lowering.

“I felt like I was working the system, because that wasn’t really me; I didn’t really have six months to live.” He still does not know if the doctor thought he would soon die or if she simply wanted to help him access benefits. But, in any case, apart from a few symptoms, his health was not yet in a dire state.

In a frenzy of determination to make the most of what was left, Bernard decided in 1992 to leave Britain for the US (just before Bill Clinton banned people with HIV from entering). He had dreams to realise. He wanted to be a Hollywood reporter. He also wanted a boyfriend who would look after him when he died.

Bernard’s eyes narrow, revisiting his thought process. “I knew in California there was an holistic, positive environment of people who were dying with AIDS but who had hope,” he says. “I was going towards the light.” He did not know what was coming.

At first life was good: interviewing film stars for various magazines, an ambition accomplished.

He stopped having sex, mostly.

“I had a huge fear of passing HIV on,” he says. But Bernard still wanted to find love, a love that could withstand the inevitable. In 1993 he started to feel unwell. He moved to San Francisco where his symptoms worsened – problems with his vision, pain in his feet, but nothing extreme.

“I had a mild case of the AIDS!” he says, laughing. By the following year, it wasn’t a laughing matter.

One of the chief markers of the immune system is how many of a particular white blood cell, called CD4 cells (the full name is CD4 T lymphocytes), a person has. If this number – known as the CD4 count – within a blood sample is below 200 it indicates that the immune system is in trouble. In someone with HIV, particularly if accompanied by infections exploiting the weakened immune system, another diagnosis was given: AIDS. (Today many doctors prefer to say “late-stage HIV”.) In 1994, Bernard’s CD4 count dipped below 200.

He spent what money he had on supplements and health food. Friends with AIDS started going blind – a grim inflammation of the retinas called cytomegalovirus retinitis.

In the years leading up to combination therapy, individual antiretroviral drugs, either on their own (mono therapy) or two together (dual therapy), were given to patients, to limited effect. Bernard was put on a series of drugs – AZT (Zidovudine), DDC (Zalcitabine), Saquinavir – that didn’t work. And worse, he became resistant to them.

But in 1995 Bernard met and fell in love with a man we will call Peter, who lived in Vancouver. Who Peter was and where he lived would prove pivotal.

“He was the man I always thought I needed; the person to take care of me while I was dying,” says Bernard. He moved to Vancouver to be with Peter. The following year the International AIDS Conference was held there, and using his reporter credentials, Bernard snuck in. He remembers the standing ovations as the data surrounding the new drugs was unveiled.

XI International AIDS Conference, Vancouver, 1996

“There was this sense that something absolutely major had happened,” he says. But as Bernard listened a horrible realisation grew. The combinations used individual drugs that he had either already taken and become resistant to, or were so similar in their chemical structure that they would most likely not work on him. “I thought, Well, it’s great that lots of people are going to benefit, but I’m not.”

He was right. By 1999, Bernard was dying; the medication not only failing but also flooding his organs with so much toxicity as to trigger chemically induced hepatitis. Peter cared for him, tended to him, a 24-hour nurse.

“My health became a full-time job,” he says, looking away, describing just the surface effects – cheeks sunken, buttocks and legs deflated; the most infamous side effects of early HIV medication, lipoatrophy and lipodystrophy, where body fat either disappears or resurfaces elsewhere.

“I had so little energy,” says Bernard. “I could choose between doing one thing per day: I could go out to the local shops, or I could cook. My world shrank and shrank. I would just sit in a chair and look out the window, out at the world, and feel like I wasn’t part of it.”

He describes this time with a kind of baffled detachment, as if recounting a childhood nightmare.

“I would just sit in a chair and look out the window, out at the world, and feel like I wasn’t part of it.”

“I knew the chances of me making the millennium were slim,” he says quietly. “I wasn’t going to see 40. We both expected me to die.”

The dynamic between the couple shifted starkly: from partners to patient/carer – and worse. “I lost my sense of myself,” he says. “I gave up my identity to become the person that Peter could take care of. He became my daddy and I was the boy: infantilised, no power, no autonomy. The relationship had to work like that, but I don’t know who that person was. I was a shell.”

Bernard was at least able to warn his family back in Britain that he was dying – a fortune many parents of gay men, especially the illiberal, did not share.

“I had found a man that was taking care of me, so I told them that so they didn’t worry I was going to die alone,” he says. His face is blank.

After Bernard made it through the millennium, he read up on the latest treatments. From this research, he and his doctor, Julio Montaner – now an internationally acclaimed HIV expert – together devised a completely new combination, using eight different drugs, including a crucial new antiretroviral medication called Kaletra.

“The combination was incredibly experimental,” he says. “It was either going to kill me or cure me.”

Within just a couple of weeks he started to feel better. The amount of virus in his blood – called the viral load – started falling. He had terrible gastric side effects, but over a period of six months, Bernard’s health improved dramatically. One day he went for a walk in Vancouver’s Stanley Park.

“It was the first time I was able to get up out of my chair,” he says. “I went out and it was like I was seeing in colour for the first time and I remember walking…” he inhales sharply, trying to keep control. His eyes fill. He swallows and starts again. “I remember walking through the park and just seeing the beauty of nature and the sky and the trees and the mountains and the sea and this feeling like, ‘This is amazing. I’m alive. I’m not going to die.’”

Bernard shifts in his chair, his face waking up, eyes darting around as if seeing a looming oasis. “It was that Lazarus moment. I came back from the dead.”

Regaining his health, his life, also meant regaining himself.

“I remember walking through the park and just seeing the beauty of nature and the sky and the trees and this feeling like, ‘This is amazing. I’m alive. I’m not going to die.’”

It destroyed his relationship.

Peter, he says, realising that Bernard would now live, finally felt able to grieve for his father who had died a few years before, a grief suppressed by the more urgent need to save his boyfriend. The grief, says Bernard, surfaced and overwhelmed Peter, but Bernard could not look after him, could not return the favour.

“Where I had been a very good patient, he wasn’t. And where he was a great caregiver, I was not. We tried to salvage our relationship but we ended up hating each other.” Bernard took a trip back to Britain to see friends, one of whom was living in Brighton on England’s south coast.

“I instantly fell in love with the place and thought, I could live here. Vancouver is beautiful but I can’t stay there; it just reminds me too much of my past, of all the ghosts, of Peter and AIDS. Now there’s going to be a new chapter to my life.”

He left Vancouver and moved to Brighton. Dispensing with the entertainment reporting of his earlier life, Bernard dedicated himself to writing about HIV/AIDS treatment, work that later morphed into campaigning to combat the criminalisation of HIV transmission.

Sex resumed too. In most cases, adhering to medication suppresses the virus to such low levels (referred to as “undetectable”) as to make HIV-positive people uninfectious – a fact that quelled Bernard’s fear of passing it on. “I remember I met someone who came here and he fucked me – the first time I’d been fucked in a decade. This sense of, ‘Oh my god! I can enjoy sex again!’”

In the early '00s he met his partner, Nick, who lives in Germany, but the distance – even after 13 years – works for them, he says: There is no danger of co-dependence.

Realising he was not going to die was step one; realising he could might even reach old age was a second, slow awakening.

“It was like being born again,” he says. “I basically lost my thirties, so I lived life again with a new vigour for everything. I could make plans – even a year or two years ahead.”

He began to see someone new in the mirror, too: someone alive, gaining weight, a complexion imbued with colour, but cheeks still sunken, the permanent telltale mark of lipoatrophy.

“I would see the scars of the battles I’d been fighting,” he says. He started having a cosmetic filler treatment injected into his cheeks to plump out the ravines. It looks natural. He no longer has to confront a reflection of the past.

Bernard begins to talk about the box above his head, and what’s in it, but before he goes any further he mentions a straight man he knows called Rob, whose story he thinks should be told.

Robert James, it emerges over the course of a morning, has the blackest sense of humour, which he deploys with a delicious cackle.

“I’m an actual heterosexual – a breeder with AIDS!” he chirps, sitting at a dining table strewn with papers and pills in his basement flat just a few streets away from Bernard. He walks with a stick. His dancing eyebrows, seasoned impishness, and reedy voice call to mind the comedian Eddie Izzard.

James was diagnosed when he was 19 in 1985, while living with his family in rural Somerset, England, and shortly before going to university – a place he had hoped would enable him to meet women.

“It was a great time to get diagnosed with the worst disease in the world with which you would sexually kill all your girlfriends,” he says with such brutal sarcasm it sucks the air out of the room. “Really good timing.”

“It was a great time to get diagnosed with the worst disease in the world with which you would sexually kill all your girlfriends.”

He also has haemophilia, the genetic disease that prevents blood clotting – in his case mostly internally, causing painful invisible bleeds that damage his joints.

Until 1985, when the medical profession started screening blood donations, the HIV virus was unknowingly contained in blood products – plasma, including a blood-clotting agent, extracted from numerous people’s blood – with which James injected himself every few days for years.

“You took the diseases of 20,000 people, concentrated them all together and then injected them into lots of people!” he says, his voice rising in satire.

Through this, James also contracted hepatitis C, a virus that has many different forms, or “genotypes”. He has several. Only some are curable.

He returns to the moment he was diagnosed with HIV. “I went in with my dad and the doctor said she’d got something to say, that she was really sorry but they’d done a blood test and I’ve got this thing, HTLV-111.” It was a year before the international medical community had agreed to call the virus HIV.

The doctor did not tell James how long he had left to live. She did not know. No one did exactly, although at the time estimates tended to be about three years.

He cannot remember what he said in response, only how determined it made him. “To make sure I had a good time when I went to university," he says, "because I’d probably not live long enough to finish the degree.”

While studying in Swansea, James was open about being HIV-positive, which spawned a thousand assumptions. Mostly, that he was gay. “I got used to coming out as straight,” he says, laughing.

Mixing in left-wing circles at college in the 1980s meant that having HIV as a white, straight man granted him immediate “cachet”, he says.

“We were in the middle of a period when identity politics was really powerful and through this [HIV] I was instantly given one. Having a friend with the ‘gay plague’ [as it was then sometimes called] was an important thing for them, so there was a sense of some people wanting to be my friend because it could add to their own credibility.”

The parents of his girlfriends did not exactly feel the same.

“They had nothing against me,” he says. “They just wished I’d fuck off and go out with someone else. They would see me as the person who was going to kill their daughter.” He pauses.

“They never admitted that.”

When relationships ended, James faced thoughts few students have to contend with.

“It would be, I’m never to going to meet anyone else again, I’m just going to get horribly ill and die,” he says, before segueing on to a broader discussion about his social life at university.

“I got drunk a lot,” he says. “To manage the ups and downs.”

Life expectancy around HIV would increase a little during the 1980s as more data was collected, but still, James realised that in all likelihood, rather than three years in total, he would probably have three years from when he first became ill.

“There’s a certain freedom in it: ‘Well, it doesn’t matter if I mess things up, because I’m not going to get to the end, so I’m here for a good time,’” he says, before admitting, “It’s bloody depressing quite a lot of the time.” And annoyingly, he adds, he didn’t get ill at university. “So I had to do the bloody exams.”

With extraordinary good fortune, James remained in relative good health for several years after university and moved to Hertfordshire with his girlfriend. “I thought, I’m gonna get ill at some point and when I do I’ve got three years. I need to build up savings so I can live OK for three years. That’s my plan.” He told his then girlfriend what they would do when that happened: “We’ll move back to Swansea and I’ll die on the Gower [a famously beautiful peninsula in the Welsh city]. Because I thought that would be a nice place to die.”

James stops, suddenly realising how dramatic this sounds – he hates the dramatic – and explains, “It becomes normal to have that conversation.”

It also became normal for him not to think about any long-term career, he says, or how much he was being paid, but to simply embark on jobs because they were interesting. He worked in various fields related to HIV or health: the drugs sector, homelessness, the St John Ambulance service. “I drifted around,” he says. Whenever anyone mentioned the word “pension” he would laugh. His friends began to die of AIDS.

The British government, meanwhile, started giving haemophiliacs who had contracted HIV “recompense” – compensation.

“Newspapers would call us the ‘innocent victims’,” says James, with sneering disgust for the judgment this implied about others with HIV.

One day, after John Major’s government had decided to give HIV-positive haemophiliacs £20,000 “to stop us taking the government to court”, James took the cheque into the building society.

“The woman behind the till said, ‘Ooh wow, you’re lucky.’”

In some regards, she was not wrong. James dodged all the major illnesses that prey on those with late-stage HIV: the pneumonias, the cancers. But as the years ticked by, with no effective treatment, James’ trust in doctors dwindled. So when combination therapy arrived in 1996 he was not exactly filled with optimism. He had moved to Brighton, partly on account of the fact that it has good coffee shops. He went to his new local HIV clinic.

“I thought, I really should introduce myself and say, ‘When I get ill and die I’m going to need you. Up until then I really don’t think there’s any point me coming in.’ But the doctor wouldn’t hear a word of it. She said, ‘You should start on treatment.’” His CD4 count at the time was 150, dangerously low.

“I said, ‘Treatment is a waste of time.’ And she got very angry and said, ‘No it’s not, it’s saving people’s lives and you’ve really got to do this.’” It was just after the Vancouver conference.

“I said, ‘Treatment is a waste of time.’ And she got very angry and said, ‘No it’s not, it’s saving people’s lives and you’ve really got to do this.’”

James thought she was talking “crap” but read about it nonetheless. “I saw some of the stuff from the conference and was like, ‘Oh my god, it works. Wow.’ So I went back to the clinic and said, ‘Alright.’ At the time they were saying, ‘We think this will guarantee you at least another six months of life.’” But within six months of taking it, he says, that expectation had swelled to five years.

The medication worked. James didn’t have a Lazarus effect like Bernard’s – he hadn’t been ill enough to experience a dramatic physical improvement – but instead came an existential one. He now had to grasp that he would live. This took years.

“It comes very slowly because there was always the fear of [drug] resistance, and then the next fear was getting a lymphoma or cancer that will kill you but it might not be for 10 years.” His friend Anna took him aside.

“She said I’ve got to stop living like I was going to die. I would still make comments like, ‘I don’t need to bother with a pension or having a healthy diet because I’ll be dead long before it gets me,’ and she got fed up with me making the same comments. That made me think, Actually, yes, I am going to live.”

This process was beset with other realisations. “There were moments of, Oh my god, I’m going to have to work another 30 years. I hadn’t thought of that. And, Yeah, I am going to retire, so I have to do something [about that]. Have I paid my National Insurance contributions? It hits you in waves. What am I going to do in work for 30 years? What do I want to do?” He started saving for a pension and thinking about work differently, seeking more security. He’s now a lecturer in law.

James found himself facing the previously unthinkable prospect of reaching old age.

“All that deterioration that I thought would be nicely condensed into a three-year period before death now might get stretched out,” he says, laughing wryly.

Something else happened: HIV went from being his most urgent, threatening illness, to the least. It suddenly dawned on James that he would have to do something about the hepatitis C, a slow-burning deterioration of the liver that can take 30 years to destroy it – decades he never thought he would see.

His haemophilia has been thrust into the foreground, too, not least because of what state he might be in physically with the condition in retirement. Over time, internal bleeding corrodes joints, which deform as they regrow.

His elbows are nobbled, distorted by the disease. Both his ankles have been operated on to fuse the bones together properly. Until those recent operations, the pain he was living with was worse, he says, than any pain he experienced through HIV.

After several relationships, James is single. “I actually like it,” he says. Partly, he adds, because he gets bored easily, but also, “I’m very bad at letting people look after me.”

In a few weeks he turns 50.

“I remember thinking it’d be amazing to get to the year 2000,” he says. “So 50 is really nice – I can say that I’m alive.”

“I remember thinking it’d be amazing to get to the year 2000, so 50 is really nice – I can say that I’m alive.”

He begins to reflect on 1996 and the effect combination therapy had on his generation. “If treatment hadn’t come along, if it had been another 10 years, I may well have died. We survived just because we were lucky.” There is a tinge of something in his voice: guilt.

“I don’t think you can live through a whole group of your peers and friends dying and not feel at some point it’s unfair that I survived and they didn’t,” he says. “I got lucky.”

There is someone else who shares this sense of luck. Someone who also knows James. She says she is privileged – “too privileged”, a description few could fit with the story that begins to unfold.

It is September 1996 and a 35-year old woman walks into Newham General Hospital, in east London. She is emaciated, broken, and close to death.

Her name is Winnie Ssanyu-Sseruma.

The doctors ask her who she is and why she is there, and run tests on her. They are aghast at what they find. A healthy person’s immune system will show a CD4 count of between 500 and 1600. Ssanyu-Sseruma’s is 1. Any passing infection could kill her. The doctors ask more questions: Where have you been? How did you get like this? What is your immigration status?

She begins to tell them. They plead with her to return, so they can tend to her, monitor her, and administer the new drugs. But Ssanyu-Sseruma is not interested. She is ready to die.

Twenty years later, Ssanyu-Sseruma sits in her living room in Walthamstow, London, revisiting that time. Her eyes are wide and fill often; her voice is soft and low – smoky. A monochrome picture hangs in the hallway behind us. It is Ssanyu-Sseruma in the 1990s, a detailed drawing drafted from a photograph of her face. You cannot see how thin she had become.

Ssanyu-Sseruma was born in Sheffield, England, in 1961, but aged 2 moved with her parents back to their country: Uganda. It was a family of seven. Now it is four.

After winning a scholarship at 19 to study in Kansas, Ssanyu-Sseruma moved east to Maryland in 1988 for an internship, and for which she was told a full medical check was required, including an HIV test.

“When I was told that the test came back positive I was thinking, Surely HIV-positive has to be good? Positive is good, negative is bad,” she says. “But the guy said, ‘HIV-positive means you have the HIV virus and there’s no cure. There’s no medicine. So we can’t determine how long you’re going to live.’ He said it in a very blasé way – as he was sitting down, getting his chair sorted. I was numb.”

From that moment, she says, her life changed dramatically. She vowed to tell no one.

“At that time, everything in the news was very grim [regarding HIV],” she says. “In Uganda HIV was well-known. The impact on people there, on whole villages – everybody just died. I didn’t know any women living with HIV [in the US] and the stigma…the combination of those things told me, ‘Just shut up.’” It also, she says, took time to understand the condition and how long she might have left.

“I thought I would just drop dead, walking on the street. So I lived life like I could die any minute. If I was sitting somewhere with friends I would think, This might be the last time I sit with these people. I would walk in a daze, bumping into people, thinking that death could come and what could that mean?”

“I thought I would just drop dead, walking on the street. If I was sitting somewhere with friends I would think, This might be the last time I sit with these people.”

The clinic in Maryland treated her sensitively, however. “I told them that I need to come to the clinic when there was no one from my [Ugandan] community there.” At the time in Uganda, she says, “there was a lot of talk about being bewitched” surrounding those with HIV. And there was another, more graphic name used instead of HIV: Slim.

“If you got it you started to lose weight. Everybody knew, and you were taken somewhere – hidden away at your request, or it’d be the family’s decision – and died a really undignified death.” By 1990 around 1 in 6 adults in Uganda had HIV.

She feared that if she was seen at the Maryland clinic by fellow Ugandans, news of her HIV status would reach her family – news that would destroy them.

In 1990, Ssanyu-Sseruma discovered that one of her brothers was also living with the virus; the same year her mother died of cancer. Her brother died of HIV-related tuberculosis in 1992. The following year, her father died of cancer.

Winnie Ssanyu-Seeruma in the mid-1990s

At the clinic, she was given a counsellor, to try to help her cope. His name was Philip. He was gay, a Christian, and HIV-positive too. Philip was the only person she told about her HIV status.

“It was really good to be able to talk to him,” she says quietly. “He was a really good source of support. One day I went into the clinic and there was a new counsellor and I said, ‘Where’s Philip?’ And they said, ‘He died.’”

Ssanyu-Sseruma’s hands come up to her face, still in disbelief. “I said, ‘Oh my god.’ Just last week he was here. This week…” Her voice fades. “That scared me to no end.”

By 1993, incredibly underweight and in worsening health, Ssanyu-Sseruma made a decision: She would die at home in Uganda. It wasn’t only for her sake.

“It would be too expensive for my siblings to bring my body back home, but they would have insisted on it,” she says. “So I thought, I’m going to make it easier for you.” She sold most of her belongings, and left the US with two suitcases.

One of them contained six months of pills – including AZT, one of the mono therapy drugs – that her clinic had given her. She returned to Uganda, to the village of her childhood, Kajjansi, knowing there would be no more drugs after six months.

“I was hoping I would die very quickly – that death would snatch me away,” she says with a snapping gesture. “I didn’t think I had anything to live for. You get infected, you have the disease, you go through this horrendous process, and then you die. Who was I to think otherwise?”

Soon after the pills ran out, Ssanyu-Sseruma contracted tuberculosis, which preys on the immune-suppressed and had seized her brother. But by then, she had support from someone else: her sister, who both knew other HIV-positive people and knew some of the clinics in Uganda.

She sent Ssanyu-Sseruma to a private practice that gave her the drugs to treat TB. Once that had cleared, another opportunistic infection attacked her: pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP). This form of pneumonia killed many people with AIDS. The clinic again provided her with the necessary drugs and again they worked.

But a third problem arose: diarrhoea. It was so extreme and chronic that Ssanyu-Sseruma knew that it alone would be enough to finish her. After several months, nothing she had tried – including what the private clinic gave her – had worked. There was only one thing left. Her aunt, who she says favours going to see witch doctors, made a suggestion.

“She said, ‘I know this person who can cure it.’ And I said, ‘I’m not going to a witch doctor.’” Her aunt insisted the man was in fact a “traditional herbalist” but Ssanyu-Sseruma was not convinced. There is, she says, a fine line between the two. She feared not only that the herbs wouldn’t work, but also that they would be dangerous.

“I thought, This [diarrhoea] is what’s going to kill me if I don’t sort it. And if I sort it through the witch doctor it [the herbal medicine] is going to kill me anyway, so what is my option?”

The fear of the herbal medicine only sharpened with the accompanying instructions.

“The herbalist said, ‘The best time to take them is at night – 4am – because this stuff will come out of you, you get through all that and then you can sleep in the day.’ It terrified me.”

She spent two days with the concoction in front of her before she could summon the courage to take it. As the herbalist had warned, a substance did come out of her. “I don’t know what,” she says. “I wasn’t about to look. But after two days? Nothing.” The diarrhoea stopped and never returned. “I couldn’t believe it,” she says.

“I was broken. I was just waking up and thinking, Hmm, I’m still alive.”

Ssanyu-Sseruma still has no idea what the herbs were, but she later heard that some herbs specific to Uganda have been found to help with diarrhoea – that this wasn’t a one-off. Although the diarrhoea had gone, the weight loss continued, and Ssanyu-Sseruma knew she couldn’t survive much longer. By then, early 1996, she had been living with the clock ticking for eight years.

“I was broken,” she says. “Broken. I wasn’t forward thinking. I didn’t like myself. I was just waking up and thinking, Hmm, I’m still alive.”

But one of her other brothers, who had moved to England as he too was born in Britain, refused to let her give in. “He told me, ‘Winnie, why are you killing yourself in Uganda when you know you can come to the UK?’” Eventually, in September 1996, Ssanyu-Sseruma agreed to a two-week trip. In London there was an opportunity.

“I thought, If I’m going to die, I need to know how long it’s going to take; I need to know how bad my immune system is.”

And that is when she walked into Newham General Hospital.

When the CD4 test came back the doctor tried to persuade her to go on combination therapy.

“He said, ‘Your body is in very bad shape. At this point, it’s not just HIV. You have AIDS.’ That was the first time I had heard that – someone referring to me as having AIDS. I broke down.” But she still didn’t agree to go on the medication.

“He said, ‘Your body is in very bad shape. At this point, it’s not just HIV. You have AIDS.’”

“I was fixed on dying,” she says slowly; the words resonate around the room, an inversion of the sunshine coming through the window. Her brother suggested she attend an HIV support group run by a charity called Body and Soul.

“There must have been 60 people – the majority were African women, and many were Ugandan women,” she says. Most HIV services and charities had been staffed by and often unintentionally directed at white gay men since the 1980s, an alienating experience for many outside this demographic.

“I just sat there and women were saying how ill they had been, and like Lazarus they had woken up and they were better and they couldn’t believe it. I watched and heard and listened, one after the other, and I thought, I want to be like them.” Her eyes glisten. “That’s what made me stay.” She remained in Britain, went back to the hospital, and said to the doctor, “I’ll do everything to be like them.”

Within six months, Ssanyu-Sseruma was transformed.

As the virus became suppressed and her CD4 count began to rise, she started eating and sleeping properly. But it was more than physical improvements. “It was a combination of the treatment and the change in my mindset – I wanted to live,” she says.

She leans in; her voice suddenly crescendos. “I’m telling you it’s like something woke up inside of me! I had energy – oh my god – everything just…you know how a flower in spring just happens? That buzz. It was amazing.”

She started attending as many support groups as she could, volunteering at some, taking courses in HIV treatment, becoming heavily involved in the HIV sector, “Networking! I could network for England!” Within a year, Ssanyu-Sseruma had met a man, with whom 20 years later she is still in a relationship, albeit on-off.

“I was able to really liiiiiiiivvvvve…” she says, stretching the word into breathy, almost sung emphasis “…like I’d never lived before, because I felt like it was a second chance at life. It was coming back from the brink.”

It’s nothing like how she lived before 1996.

“The way that you appreciate life, the way that you deal with people,” she says. “I feel like I’m a lot kinder to myself. I think through things and my relationships with other people. I really wanted to be a good person, a supportive person, and for me it is a very conscious living…” She starts to bang her hand on the table, beating out the syllables of “living” as if wanting to shake other people to live vigorously, to vibrate with life.

Today, Ssanyu-Sseruma works as an international development consultant, monitoring community-based HIV and health projects. She also sits on the board of the Kaleidoscope Trust, which seeks to improve life for LGBT people around the world. But there is one other thing she does, which she mentions only when asked what makes her happy now.

“It’s just how I am now. Living with a purpose.”

“I have this project that I started in my village [in Uganda],” she says. “It feeds vulnerable kids breakfast before they go to school.” The scheme, called Bridging a Gap Community Initiative, began feeding 44 children, half of whom, a local leader told Ssanyu-Sseruma, would have died without the daily meal. Now they serve 150 children.

“It’s very fulfilling,” she says, smiling, eyes flickering up as if back in Kajjansi. “It’s just how I am now. Living with a purpose.”

Last year, a group of people who have been living with HIV/AIDS for decades published a declaration, calling on the world – which has often looked away – to hear their experiences, and to provide help where it is still needed. It contained a phrase that rings out over the struggles of Bernard, James, and Ssanyu-Sseruma:

“We had the audacity to survive.”

For Bernard, this audacity came at a price. He starts talking about the box, sealed above him. It is full of photos. Photos of him and Peter.

“I can’t look at those photos,” he says. “Guilt. I feel guilty that Peter took care of me and then I left him. I said, ‘I cannot do this.’ I think that was my last moment of selfishness. It wasn’t just that I needed to take care of Peter, it was also the idea that I could leave all the awfulness behind – the hardest period of my life – and reinvent myself.”

In the end, he says, it came down to a single impulse: self-preservation.

Bernard walks down the stairs with the photographer, Laura, out on to Brighton’s pebble beach. A mother and daughter are perched on little fold-out chairs, chatting. As Laura crouches to snap Bernard ambling along the front, the mother and daughter regard the scene, quizzically. Why are they taking his photo? What’s so interesting about him? It’s a fair question. Millions have the virus but don’t have the drugs – without which they’ll never have a Lazarus effect.

Bernard stops and turns toward the expanse. He looks out, below the blue-grey horizon and into the benign indifference of the waves.