The walls were made of sandstone. There was no window, just bars on the door through which a landing stretched out to row upon row of cells. Aged 20, and a thousand miles from home, Keith Biddlecombe was locked up alone – all the queers were.

He was in a military prison in Malta, after being arrested and interrogated while serving in the Royal Navy. It was 1956. But a month after arriving, a guard would unlock his door and deliver news that would ricochet through his life for the next 60 years.

The news concerned an officer that Biddlecombe had had sex with and, under extreme duress, told the authorities about. What the prison warden told him that morning about the officer had immediate, as well as long-term, consequences.

Biddlecombe would have to travel back to England, to another prison, to serve out the rest of his sentence.

“I was trying not to think of what he’d said by packing my bags, to do something to take my mind off it,” he says.

He did not know then that he would spend the rest of his life trying to block it out.

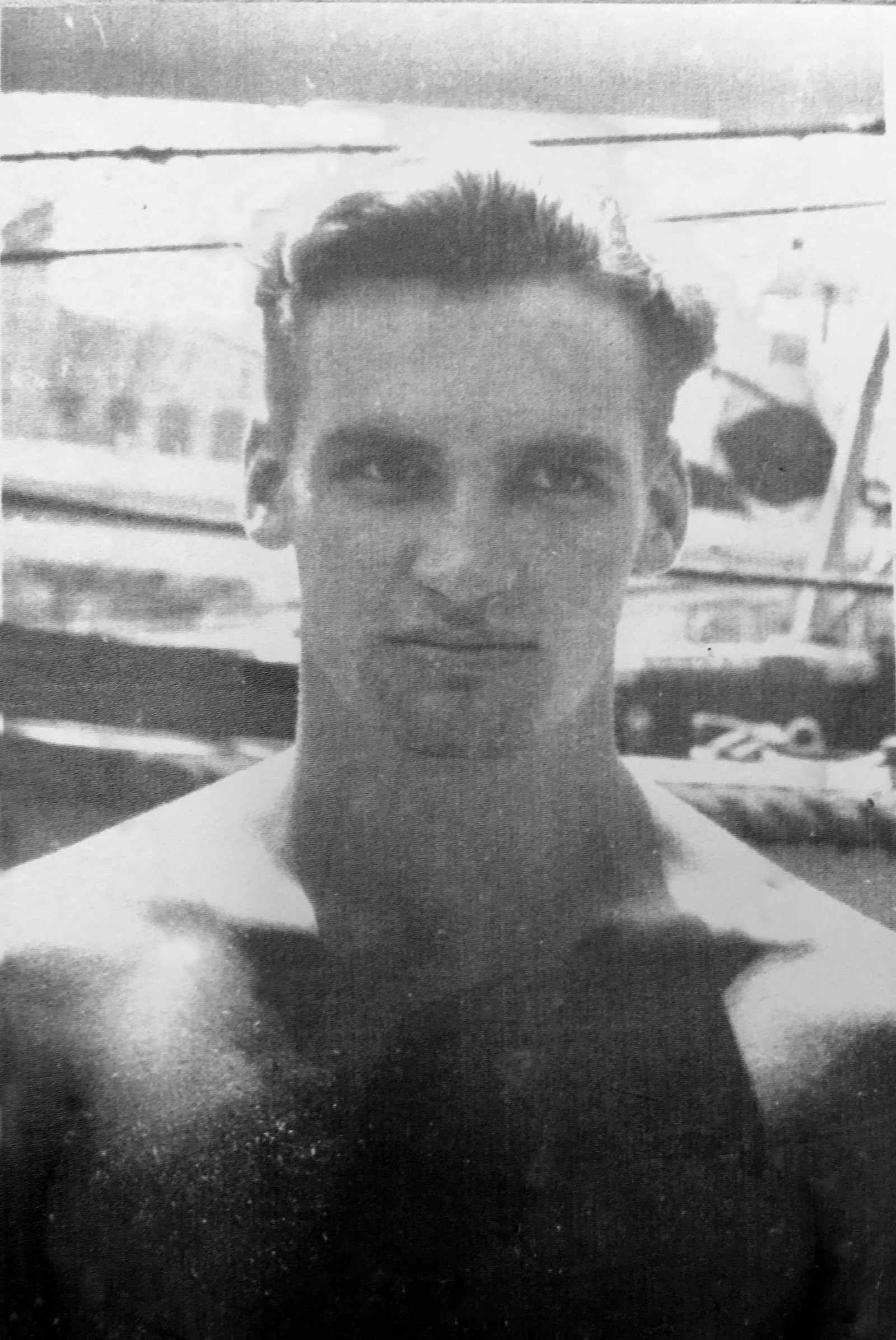

Today, Biddlecombe sits in an armchair in his two up, two down house in Brighton, removing his glasses and apologising for the tears he rubs away. He is old now – 81 – but the events of his youth, when Britain hated gay men, still intrude.

It is 50 years this month since the laws forbidding sex between men were overturned in England and Wales – laws that led to the conviction of World War II codebreaker Alan Turing, the incarceration of Oscar Wilde, and thousands more jailed like Biddlecombe. “I was imprisoned for what I am,” he says.

He talks slowly, carefully selecting words. His breathing is laboured following a heart bypass, but in almost three hours he does not take a single sip of water. He wants people to know what he – what all of them – endured.

There were four brothers. Biddlecombe, born in 1936, was the youngest; a happy, friendly boy who grew up in the Isle of Wight with a Roman Catholic mother and a father away at war.

Along with six or seven other local children, he would spend endless days on the beach or in the woods playing Robin Hood with bows and arrows.

Later, finding himself to be an average student at the nearby secondary modern school, and with his father and an elder brother in the Royal Navy, Biddlecombe decided to enlist too. It was 1952.

“I could get away from home,” he says, flatly, the youthful excitement of possibilities now heavy with what lay ahead.

“At that time I had never heard the word ‘homosexual’,” he says – nor “queer”. It would be another decade before people used the word “gay” to mean anything other than happy, and another 15 before sex between men became legal.

The law against “buggery” – as the offence was known – dated back to 1533, but in 1885, the related offence of “gross indecency” was added, outlawing any sexual contact between men.

As such, the law did not only mean jail; its impact cascaded out, controlling and suffocating: an all-pervasive prison. It meant silence, ruinous shame for anyone exposed and innumerable sham marriages. Generations of gay men (there was no law against lesbianism) died with the lie. Many killed themselves. None enjoyed the oxygen of liberated love.

There were other words, too: invert, pervert, fairy, abomination. Biddlecombe had never heard those either, growing up in rural postwar Isle of Wight. “Although I’d been a practising homosexual since I was 9 or 10!” he says.

There was a boy in his school called Martin Smith. “He introduced me to what was going on, and I thought, This is great. It’s what I wanted.” But somehow Biddlecombe knew that it “must be wrong”. He told no one.

Ten days before his 17th birthday, Biddlecombe joined the navy; a move that would whisk him around the world and set him on a path that would lead to prison, and worse.

At first, however, it led mostly to a much-needed education, and much-wanted sex.

“During our training we had a lecture by a doctor and he told us about ‘social diseases’. He said, ‘Don’t play with another fellow because one of you will stay like it.’” The doctor also used the word “homosexual”.

“I came out of that room thinking, My god, I’ve been one of those for years and didn’t know it.” He did not realise, however, that gay men exist everywhere. “I thought homosexuals were only in the navy.”

After training first in barracks in Portsmouth and then on HMS Indefatigable, Biddlecombe was assigned a ship, the Mauritius, and sent out to sea. But despite now knowing he was gay, he had no idea how to act upon it onboard ship. “I was thinking, How do you recognise somebody [as gay]? How do I make it happen?” The question would soon be answered.

As a “messman” – a junior seaman who serves food and clears plates – Biddlecombe had to carry trays of food from the galley to the men.

“I was going up these stairs and couldn’t do anything with my hands,” he says. “There was a fellow there and when he came level he kissed me and held the kiss until I got up onto the floor. I spoke to him and he told me what was going on, that there were gays on the ship. I thought, Fantastic! I don’t have to look for them – I’ve found one!”

From then, he started learning who else there was like him.

“Life sort of blossomed,” he says, smiling and looking out the window for a moment. Figurines perch behind him, a patterned carpet beneath, and above, in the attic, hangs a multitude of colourful costumes – a clue to the life that eventually awaited.

As well as clandestine meetings with other sailors onboard, Biddlecombe found further dalliances ashore.

“There was a navy hostel where you could go, you paid 5 or 10 bob to stay the night – these were just chalets and doors were open. If the door was open, you looked in, and if you fancied it, you carried on.” Such trysts were rife, he says, even among heterosexual navy men.

“Those married men went ashore and got drunk and screwed whatever came to hand. They accepted it [sex between men] quite happily. There were very, very few people that I ever came across that didn’t understand it. It was all part of their life as well as ours.”

Assured of his feelings for men and certain he did not want to marry a woman, the navy offered Biddlecombe the prospect of an alternative life, for a while at least. “I was happy, thinking it’s going to give me a living for 12 years,” he says.

But then in 1956, after a trip to Singapore, he was sent to Malta on the Reggio, part of the Amphibious Warfare Squadron. Life – and sex – continued as normal for a while until a man, who to this day Biddlecombe will not name, propositioned him.

“He had just got a ‘dear John’ letter from his girlfriend and he came to me because he wanted sex. Against my better judgment we got together. He wasn’t gay. All he wanted was a port in a storm.”

One night they went up onto one of the mess decks that were empty. “We went in there, closed the door,” he says. “I was lying on one bunk, he was lying on the other. We had shorts on.” They did not have sex.

“We were just lying there thinking of going to sleep,” he says. But then the officer of the watch came round, with the petty officer, to do inspections – the former of whom Biddlecombe had previously had sex with. “He saw us and tried to shove the [petty] officer back out but [the petty officer] also had a torch and said ‘there’s something there’. On came the lights.”

In an instant, Biddlecombe knew what this meant. “I got up and said, 'Right, that’s it, we’re caught, get on with it.'”

But he did not know what the procedure was; that first they would be questioned separately by their superiors, or that it would not only be an interrogation. “They said, ‘We want the names of the people you’ve slept with.’”

Without supplying these names, Biddlecombe was told, he would be given five years in prison. But if he gave the names, the sentence would be reduced to 12 months. Initially, Biddlecombe refused, uncomfortable about incriminating anyone. But then, he says, “My divisional officer said, ‘It’s OK because all they’ve got to do is to deny anything happened.’”

There was an army officer who Biddlecombe had been with ashore, so, trusting the advice from his officer, he told them about this, although he did not know the officer’s name.

He also did not know that as part of the investigating procedure he and the man he was caught with would then be taken to the sick bay, and that the ship’s doctor, with officers present, would perform an examination on the 20-year-old so intrusive that he would begin to mentally disassociate from what was happening.

“It was a metal cone,” he says, blankly, as if trying to reject the memory, “which they put in." He looks away. “Then they pulled the handles apart.”

Biddlecombe does not elaborate at first. He starts to change the subject, reverting back to when they were caught, before eventually returning to what happened in the sick bay.

“I had to grit my teeth and close my mind down,” he says. “It was as painful as you can imagine. A gross violation of me.” After looking inside him, they took the metal cone out.

“They said there was bruising which could not have been caused by anything other than sex.”

He begins to describe the experience as humiliating but is frustrated at the inadequacy of the word and, unable to conjure a better one, gives up. With a look of detachment he adds, “I tried to cope.”

The other man, he says, came out screaming. He was shouting, too: “I’m not a fucking queer.”

The law did not care. The government, the judicial system, the navy, and society generally did not recognise sexual orientations or identities, only behaviour that transgressed the sexual norm.

Next was the court martial: Military law mirrored criminal law in this matter and so the following day, the two men stood trial in Fort St. Angelo, Malta.

Biddlecombe thinks he pleaded not guilty to the charges – gross indecency and buggery – but he cannot remember. He describes the process with such disconnection, in part because they were barely questioned at all (“you stand there, you’re charged”), it is as if he wasn’t even there.

“The lawyers were doing all the chatting,” he says. “It was very strange – I’d never been to court before.”

The charge of buggery was reduced in court to attempted buggery, through lack of evidence, but both men were found guilty of this and of gross indecency. As expected, they were given 12 months. Biddlecombe’s papers were docked, the corners cut, removing any references and in turn little hope of rehabilitating himself on the outside world.

The other man was immediately sent back to England to serve his sentence. But Biddlecombe was kept in a military prison in Malta – the jail with the sandstone walls. He was held there to await the trial of the army officer he had told his superior about. Even without a name supplied, the military authorities had deciphered who it was and captured him.

During that month, in a cell measuring 8 feet by 6, all Biddlecombe could hear at night were the guards – a tranquillity that was later not afforded him. In daytime he and the other inmates were set to work, making football nets. Sometimes they could stretch their legs in the courtyard.

But it was here in his cell in Malta, that after that first month, the warden unlocked his door one morning to deliver the news about the army officer that would stay with him forever.

“He said, ‘Pack your bags, you’re going home.’ And I said, ‘Well, what about the trial?’ And he said, ‘No trial. The man shot himself. Blew his brains out.’”

The news itself hit like a bullet.

“I sat down on my bunk in my cell and cried my eyes out,” he says. Although he tried to distract himself with packing, it could not stop the torrent of taunting thoughts.

“I thought, If I hadn’t said anything he would still be alive. It’s my fault. I never thought in my wildest dreams that someone would do that because of me, that a man would kill himself because he slept with me for one night.”

“It was all mixed up: I thought, Why would he do that? Life being gay is not that bad, you can cope – at least, I can cope, why couldn’t he?”

Biddlecombe tries to conjure an explanation.

“Being a military man, a military family, 60 odd years ago, if his family found out he was gay… It would be shame. He couldn’t hack it.”

He looks around the room, scanning back and forth as if still looking for reasons.

“I have tried hard not to think about it,” he says. “A lot of it is blocked out. It was my only way of coping.” But then he stops and looks straight ahead again.

“That man’s death I have carried with me for the last 61 years.”

Back in England, he was sent to Shepton Mallet prison in Somerset. Built in the 17th century, it was originally for civilian use, but from 1945 it became a military jail, housing nearly 300 inmates, some court-martialled for murder. It also contained an execution block.

There was a similar-sized cell for Biddlecombe here, but with a small window high up. Again he was locked up alone, in keeping with five other men who were also serving sentences for the same offences. Everyone else shared, ensuring they knew why those six men were there.

Biddlecombe was still 20. Court-martialled, disgraced, and imprisoned, he had to write to his parents in the Isle of Wight. He was only allowed to send one letter per week, with a pencil, on a small sheet of paper.

“I explained that I’d been dismissed of Her Majesty’s service, and imprisoned for 12 months for gross indecency and buggery,” he says. “I said, ‘If you want to see me I will come home. If not, I will make my own way in the world.’”

His mother wrote back.

“She said, ‘We all love you. We want you to come home.’”

This wasn’t the only letter he received. A woman he had known most of his life, a family friend who had looked after him as a young boy when he became a chorister, who would give him lunch after church, wrote a letter. One line he has remembered his whole life: “She said. ‘We are not ashamed of you, we are ashamed for you.’”

Like her, not everyone in England agreed with the buggery and indecency laws. Following the second world war, it was being implemented with such increasing frequency that by the mid-1950s more than 1,000 men a year were being imprisoned. Some, like Alan Turing, who had helped secure Britain’s victory against the Nazis, chose chemical castration over jail. Turing subsequently killed himself.

While Biddlecombe served his sentence, a report was being prepared that would begin the process of overturning four centuries of legal oppression against gay men.

The Wolfenden report, as it became known, was commissioned by the Conservative government, and comprised a committee of experts, led by Lord Wolfenden, who conducted interviews with people affected by the laws. The report concluded that “homosexual behaviour between consenting adults in private should no longer be a criminal offence”. But the government, at the time, ignored the advice.

Biddlecombe, like more than a thousand others, remained in jail. The relative peace of the Maltese prison was not replicated in Shepton Mallet.

“There was one evening where a chap I’d worked with in the workshop started shouting, which went on to screaming,” he says. “He screamed all night. I thought, For goodness' sake, shut up, not realising that the man was going insane.”

The man was taken away in a straitjacket.

For Biddlecombe, the immediate fight was to keep his sanity. He starts to explain how he compartmentalised his thinking into three areas: focusing on what he had to do, which in his case was working in the prison mending boots and exercising when he could; dreaming and hoping for things in an attempt to cheer himself up; and ignoring thoughts of the outside world and what might lie ahead.

“I’m a sensible sort,” he says. “That’s how I survived.”

He also had sex. Every single week. On Thursdays only, inmates could do three things: play games, change their underwear, and shower. The warden would send the prisoners down landing by landing.

“Then we six [the ones serving sentences for buggery or gross indecency] were sent to shower together,” he says. “The screw who was a naval chief petty officer – and gay – took us down, we had a shower, he then turned off the water, turned on the steam and said, ‘Right fellows, you’ve got 10 minutes.’” It wasn’t long enough for anything too involved, says Biddlecombe, smiling, “but enough”.

His 21st birthday also happened to fall on a Thursday, a coincidence that led to an event upon which the rest of his life would pivot.

They had two deliveries of post each day. After the first arrived with nothing for Biddlecombe, he thought perhaps his family might send a birthday card for the second delivery. But nothing came. He assumed the worse: that the disgrace meant rejection after all.

“We were just about to go up to our cells and be locked up when the master-at-arms [naval prison officer] came out of his office with his hands behind his back. He called my name and said, ‘It’s your birthday, isn’t it?’ And I thought, Bugger’s been looking at my records. But he said, ‘Do you know how I found out? Because this lot came for you today,’ and from behind his back he brought out a pile of birthday cards."

At this, Biddlecombe begins to cry, stopping for several moments to contain himself so he can continue the story.

On the top was a card in a fancy box covered in satin. It was from his mother and father. On top of that was a half-pound of sugar – which would have taken him a week in the prison cobbler’s to earn enough money to buy – and an apple and orange, “something which we never got in prison”. They were presents from the prison staff.

“I went back to my cell with this lot, dropped on the bed and cried my eyes out.”

As Biddlecombe removes his glasses to wipe his eyes, now wide and blinking, he looks grateful, even today. But that was not all. Because inmates were allowed to play games on a Thursday, that evening, as ever, he sat with his friend Paddy and played chess.

During the course of that evening, “People I didn’t even know came up and said 'happy birthday’.” His voice cuts out again as he tries to remain composed. “They left sugar, sweets, chocolate. I went back to my cell that evening, my arms full, threw the lot on the bed and cried.

“It was something which you can say changed my life, because I was there thinking, What am I going to do when I get out? How am I going to face my parents? I hate people in the outside world. But when this happened I thought, If people in here can be that kind, then there must be kindness outside that I may be able to latch on to.”

This kindness propelled him through everything that followed. He left prison after six months, thanks to good behaviour, returned to his family, and devised a 10-year career plan to override the lack of references and the stain on his record.

First, he worked in a coal mine, where he made a further discovery: that despite the cruelty of having been imprisoned by his own country for a victimless crime, people “are not evil and wicked and against me for what I am”. From here, he worked in department stores, eventually becoming a window dresser before turning his creative talents to making costumes.

He shows me up into his attic, where racks of elaborate, beautifully crafted fancy dress still hang – the ones he hasn’t sold to costume hire shops.

Ten years after he left prison, and a decade after the Wolfenden report, the Labour government finally took its advice and repealed the laws incriminating gay men with the introduction of the Sexual Offences Act 1967. What did Biddlecombe think at the time?

“I took a deep breath and thought, About bloody time,” he says. “But as usual with law, what is it actually going to mean? Is it going to get better?” In gay pubs at the time, he says, it was the “topic of conversion – some people thought it was good, some people like me were a little sceptical, saying, ‘They say we’re going to be free, but let’s wait and see. I’ll believe it when it happens.’”

The repeal, although still today referred to as the “decriminalisation” of homosexuality, was only partial. It allowed sex between men only in private – precluding, for example, sex in rented accommodation – and only if both parties were over 21, and not members of the armed services. It also, says Biddlecombe, sparked a spate of hate crimes.

But it triggered the beginning of emancipation.

Now out of prison for 10 years, Biddlecombe was himself beginning to feel it. “One evening at home, I looked into a mirror in the kitchen and said to myself, Why the hell can’t somebody fall in love with me?” He realised in that moment that he liked himself. “There’s no point hating yourself, is there?” he says.

He had relationships, seven in total of several years each, which he calls “affairs”; the last ended not long ago.

In that time, Biddlecombe witnessed a revolution sweep by. But he did not become involved in activism. He was, he says, just trying to get on with life outside prison. “I was quite happy, quite content.”

And so, as a few dozen marchers swelled to hundreds of thousands, as discriminatory laws were torn down one by one, and as the pink triangles pinned onto gay men by the Nazis morphed into millions of fluttering rainbow flags, Keith Biddlecombe carried on, working, loving, living.

He never forgot what was done to him, or the man who could not cope with the shame. But he is not angry. “I blamed myself for being caught,” he says.

The government has offered pardons for all those convicted under the old laws, but Biddlecombe isn’t interested. “We have never committed a crime,” he says. What he wants is compensation, something that would actually make a difference to his life. He still lives in a rented house.

Today, he finds himself the object of admiration from those who never knew what life was like before. Last week, he received a Pride award from Attitude, the gay magazine, which baffled him and which he dedicated to all those who suffered as he did. But he is left with a transformed world that he can still enjoy.

“I like being gay,” he says. He talks about the gay friends he had over the previous night for a fish supper. “I have now got to the state when I can do that sort of thing, incorporated into my life, and I’m happy.”

What advice would he have for young gay people today? Biddlecombe thinks for a long time before answering.

“Live your life as you want to,” he says, his eyes flickering as if seeing himself six decades ago with those other young men, ignoring the law for the sake of love. “Be faithful to yourself."