This is Part Three of a BuzzFeed News investigation

Part One: Landlords Are Offering Young Men Free Rooms In Return For Sex And Facebook Is Letting It Happen

Part Two: This Is What Happens To Men Forced To Offer Sex To Avoid Sleeping On The Street

A 24-year-old man called Adil is talking about how he became homeless – how he started running away at 14 because his mother would beat him for being “feminine” – when he suddenly begins to describe what he witnessed after he left a homeless shelter to work in a gay sauna.

“Individuals would literally live there,” Adil tells BuzzFeed News, while sitting in the offices of Depaul UK, a homelessness charity. “There were open lounges where they could sleep and cabins where they could lock themselves inside. Our manager was completely aware, the owner was completely aware, so we just ensured that everyone was safe and the facilities were habitable.”

Other homeless gay men who spoke to BuzzFeed News would later echo Adil’s experiences – accounts that were also confirmed by the saunas themselves.

Every gay sauna in London that opens overnight conveyed the same reality to BuzzFeed News: The housing crisis has become so extreme that men are resorting to sleeping there to avoid being on the street. And the scale of the problem is so great that some saunas are having to change their admission policies, fearful of contravening licensing laws.

This, however, is just the start.

Last month, BuzzFeed News published the first two parts of an investigation into men having to offer sex to other men just for a place to stay – the gay experience of the “sex for rent” scandal – and the array of dangers they face.

In the third part of this series, BuzzFeed News today reveals how gay saunas are now at a new frontier of the homelessness epidemic, mopping up the capital’s acute shortage of affordable rental properties and social housing.

As well as providing shelter to men with nowhere else to go – men who often form part of the invisible homeless population – such saunas are also trying to manage and contain a problem that for some has become unmanageable.

Through interviews with sauna employees and owners, we reveal for the first time a further dimension to this: Homeless heterosexual men are sleeping in gay saunas, too.

“It was more than a couple of dozen,” says Adil about the number of people who would regularly sleep at the sauna where he worked because they had no other option.

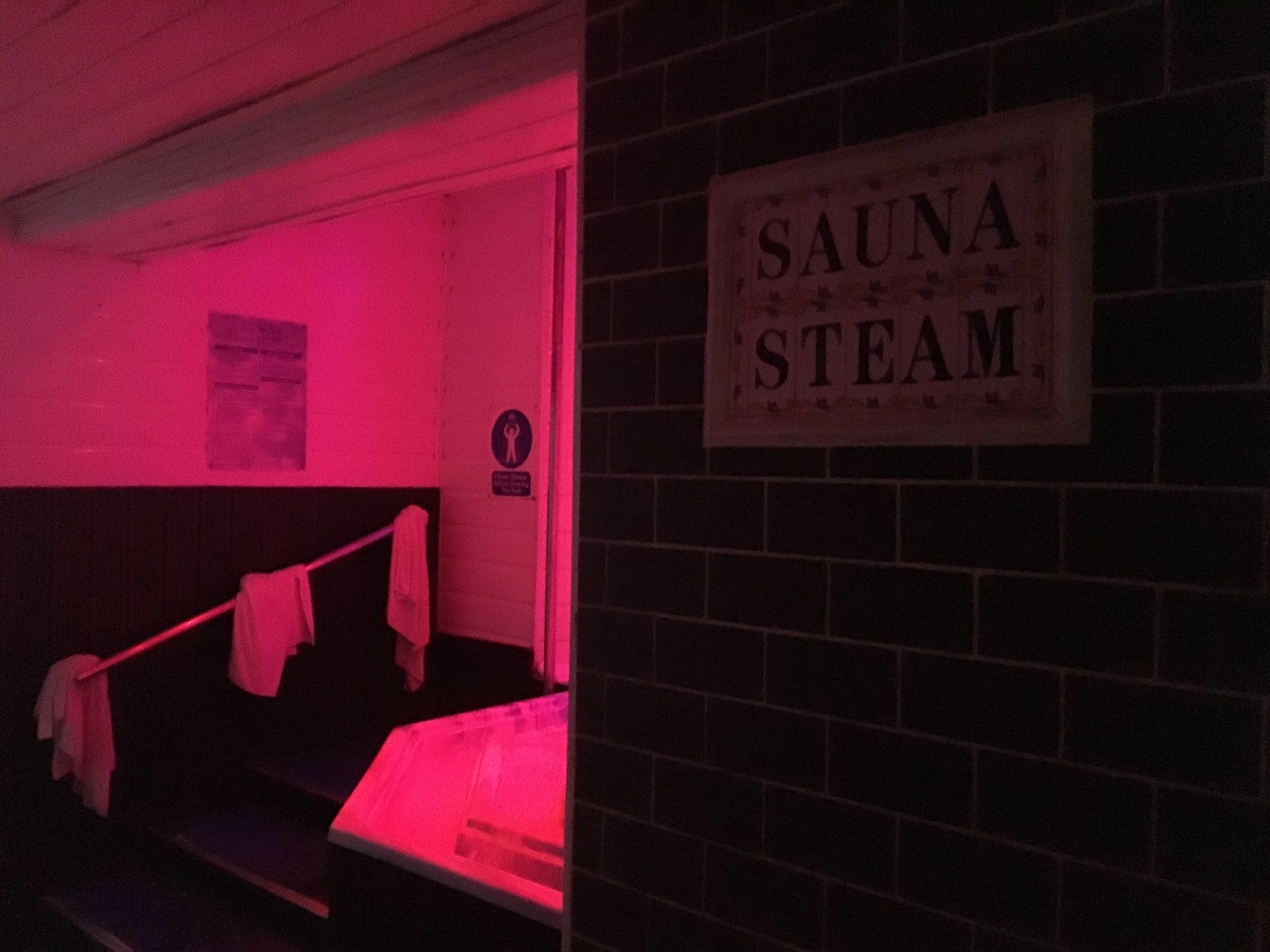

The sauna is called Sweatbox. Nestled in a quiet side street in the midst of Soho, central London – the heart of the LGBT scene – Sweatbox, which also contains a gym, has like many gay saunas both communal areas in which to relax and private booths with mattresses on which to rest.

“It was prevalent enough for us to make it a ‘no longer than eight hours’ rule,” Adil says, explaining that the admission policy recently had to be changed to manage the problem: Customers now have to leave after eight hours.

Having been homeless as a teenager, having lived at a shelter and now working with LGBT young people, Adil knows what hazards await gay people with nowhere to go. Sleeping in saunas, therefore, is to him not only “a sign of the times” but also vastly preferable to other options. “Would you rather they were in the sauna or on the street?” he says. “I would still consider the sauna a safer place.”

Overseeing this comparative safety is the owner, Mark Ford. At 54, he has been running Sweatbox for over a decade and in the last few years has been balancing two competing stresses: trying to help gay men falling victim to the housing crisis, but also ensuring he sets boundaries that adhere to the restrictions on his business. There are, he says, no easy solutions.

“There was a point at which a Polish guy – who was very sweet – had his post redirected to us,” he says. “At that point we had to say, ‘You cannot live here.’ I’m not licensed as a hotel or as accommodation in any other way, so there are legal requirements.” As such, says Ford, “I might even shorten [customers’ stay] to a six-hour rule.”

The man using the sauna as his postal address was the final straw, pushing Ford to introduce the new eight-hour rule. But even this only contains the issue within certain parameters. “There are still people who stay for eight hours and on the dot they leave. They take their belongings with them,” he says. They often return, however, a few hours later.

“There are times when we know that somebody is effectively living there – they don’t have any other home,” he says. Keeping within the terms of their license while also being compassionate becomes very difficult. “What we’ve done in the past is to say, ‘This can’t go on forever, so be on notice that you need to do something about this but we’re not going to immediately throw you out.’ They have to know they’re on borrowed time.”

Denholm Spurr, a 27-year-old gay former homeless man who last month revealed to BuzzFeed News the sexual violence he suffered from landlords while exchanging sex for rent, says at times Sweatbox was a lifeline.

“If I had the money to pay one entry that was enough for me for four days,” he says. When he had no money and nowhere to sleep, Spurr would go there on Mondays because on that day it allows under-25s in for free.

“They eventually brought in a system where if you stayed past midnight then they would charge you, but for many years Monday nights were fine because I knew I had somewhere to stay,” he says.

Against a backdrop of having to have sex with a succession of landlords, Sweatbox, for Spurr, was a break from exploitation. His use of such venues is typical among many who spoke to BuzzFeed News, describing it as part of the mix of ad-hoc, short-term arrangements on which they relied to avoid sleeping on the street: a few nights on a friend’s sofa, a night with someone they meet on Grindr, a couple of nights at a sauna, then repeat.

The trouble for sauna owners, however, is that there are many more men like Spurr.

“None of us can actually fix this problem on our own,” says Ford about the homelessness crisis facing the LGBT community. “We can’t supply them a home, but at the same time we don’t want to chuck them out on the street. Any of us can only do so much.”

It also isn’t only gay men who resort to saunas.

“We had a period when we would get itinerant workers – non-gay guys coming over from Eastern Europe and wherever else – who were coming to London to work and they found out about this amazing place on the cheap,” says Ford.

Because Sweatbox is right in the centre of London, the most expensive area in Britain, there are few places to stay for £70 per night let alone the £17 entry fee to the sauna.

As Ford and others explain, those who stay in gay saunas overnight come from a range of personal circumstances: from the straight migrant worker who cannot afford London rents, to the young gay sofa-surfer who does not consider himself homeless, to gay men who hail from other parts of Britain and have jobs in London but do not earn enough to pay for the commute as well as for rent.

As previously reported by BuzzFeed News, the average monthly rent in London – for a flatshare – now exceeds £750, and the average 18-to-21-year-old earns between £1,270 and £1,361 per month.

Neil – who wanted his only first name mentioned – works at Chariots, perhaps the most well known of gay saunas. It was previously a chain, but over the past few years has seen London branches in Farringdon, Streatham, and Shoreditch close, the last of which – in an area of prime real estate – was sold to developers. Last month, Chariots’ Waterloo branch closed, leaving now only its large Vauxhall venue. Neil used to work at Waterloo but recently moved to the only remaining location.

“At the Waterloo branch, there was a 24-hour operation [in terms of opening hours] seven days a week, so we had to monitor people … and make sure they’re not staying over the 24-hour period,” says Neil. “Some weren’t even living on the streets, some were working but didn’t have any accommodation, so they would stay overnight and then leave in the morning. It’s not the traditional person living on the street.”

He remembers one particular customer “who came into the Waterloo [branch] for many years”, says Neil. “He lived in the Midlands but worked as a chef in London, so he came in on the Monday and would stay over at the sauna every evening, go to work every morning, and then at the weekend go back.”

It is the only solution for many trying to survive in London today, he says. “The rents are so high and even if they’re on a wage they can just about afford the travel into London, but they can’t afford the rent as well.”

Sometimes Neil gets to know these customers. “At the Waterloo branch, if I noticed someone was there four or five days in a row then I’d enter into conversation and say, ‘Are you working? Are you living in London?’ And it tends to be they’re working but have no accommodation.”

The Vauxhall branch closes every morning at 8am, so rather than staff having to monitor who is outstaying the allowed 24-hour limit, all customers have to leave. With the amount of business at the weekend, says Neil, it would be impossible to monitor all visitors to ensure no one was outstaying the 24 hours. But the situation overall is “extremely difficult” to manage.

Most of the customers, in Neil’s experience, are not like Spurr. “They’re in their late thirties to late forties,” he says. “I think it’s a lot easier for younger guys to move in with their friends, but for the older generations it’s not so easy and there’s a certain [stigma] – that an older person should have their life sorted out and not living on people’s sofas, so I think it’s harder for older people.”

As with Sweatbox, Chariots also has straight customers. At this venue, says Neil, they come “during the daytime, they don’t stay overnight. They just come in here and watch TV and go after five or six hours. Maybe because it’s warmer, rather than being on the street.”

Regardless of sexuality, saunas across London are having to contend with how the housing problem affects the community. Employees at Pleasuredrome, one of the other major gay saunas in central London, and the Locker Room, a smaller sauna in south London, also confirmed to BuzzFeed News that men sleep there.

It is “common”, says an employee at the Locker Room, although his counterpart at Pleasuredrome was unsure of the personal circumstances of the men who sleep there. “I can’t really comment on whether they’re homeless or not,” he says, adding that some “come with their suitcase”. Pleasuredrome has a maximum stay of 12 hours and its “deluxe pods” – private cabins – have an eight-hour time limit.

Mark Ford at Sweatbox, meanwhile, wants to do more than simply try to manage the overspill from the housing crisis. He wants to help gay men find accommodation and find each other.

“My dream,” he says, “is to open a more community-based business,” in which part of Sweatbox would be used for gay men who are looking for flatmates to meet. “What I see in twentysomethings is those that end up in a gay flat-share get through life much better – you need a support network when you’re gay and [with gay] flatmates you’re launched into a community.”

By connecting gay men who may have fled to London in order to be with their own community – to be themselves – but who cannot pay the high rents, says Ford, at least some could be prevented from resorting to exchanging sex for shelter or sleeping in a sauna.

“The real heart of it,” he says – beyond all the economic problems – “is loneliness, isolation. I think a lot of these kids wouldn’t be homeless if they hadn’t fallen through the cracks and gone down a path from which they couldn’t return.”

Adil, his former employee, knows this from experience. For him, though, it’s policies and perceptions that need changing just as much. He grew up in a Muslim, Middle Eastern British household – not easy, he says, when you’re queer. His mother beat him with her fists, feet, and any implement that came to hand: “a skipping rope, brooms, sandals”, even a radio antenna. But when he fled he found no help.

“I wasn’t considered vulnerable by any local authority,” he says. So he would go home. In order to do so, he had to comply. “I would make promises that I would change,” he says. What he means is that he would promise to be straight. It was, he says, “another padlock on the closet”.

When Adil finally left for good and ended up in the homeless shelter, he was the only gay person there. Finding a job at Sweatbox, then, wasn’t just about the money; it was to be around other gay men – some of whom, he soon realised, were homeless, queer, and isolated too. People who go unnoticed.

There is something, therefore, that Adil cannot understand: that despite what LGBT people can suffer at the hands of families, employers, landlords, and wider society, and despite the high rents and low housing stock in the very areas the community flocks to, the authorities that are meant to protect those in need often do not help. “Being gay and homeless,” he says, looking out the window suddenly, “isn’t considered ‘vulnerable’.”

Some names have been changed.