Bronze stilettos perch on a shelf behind James Dawson’s front door. To the left sit plimsolls. Scan between them and there in cartoon simplicity is the story about to unfold. Left to right. A to B. Man to woman. Except that Dawson is not a man and the story that follows is far from simple.

He ushers BuzzFeed News into his living room, pours tea, and arranges Jammie Dodgers on a plate. We are here in his Brighton home because he needs to tell the world something.

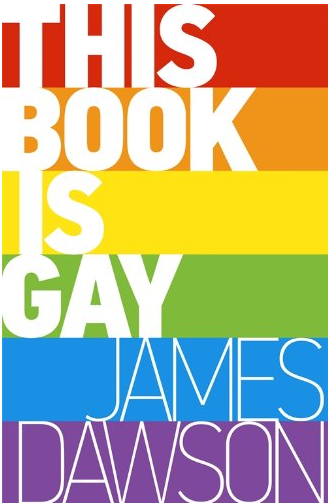

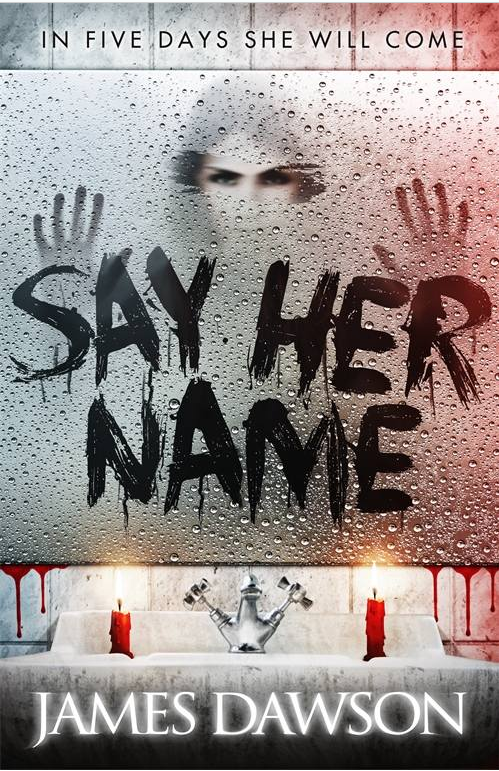

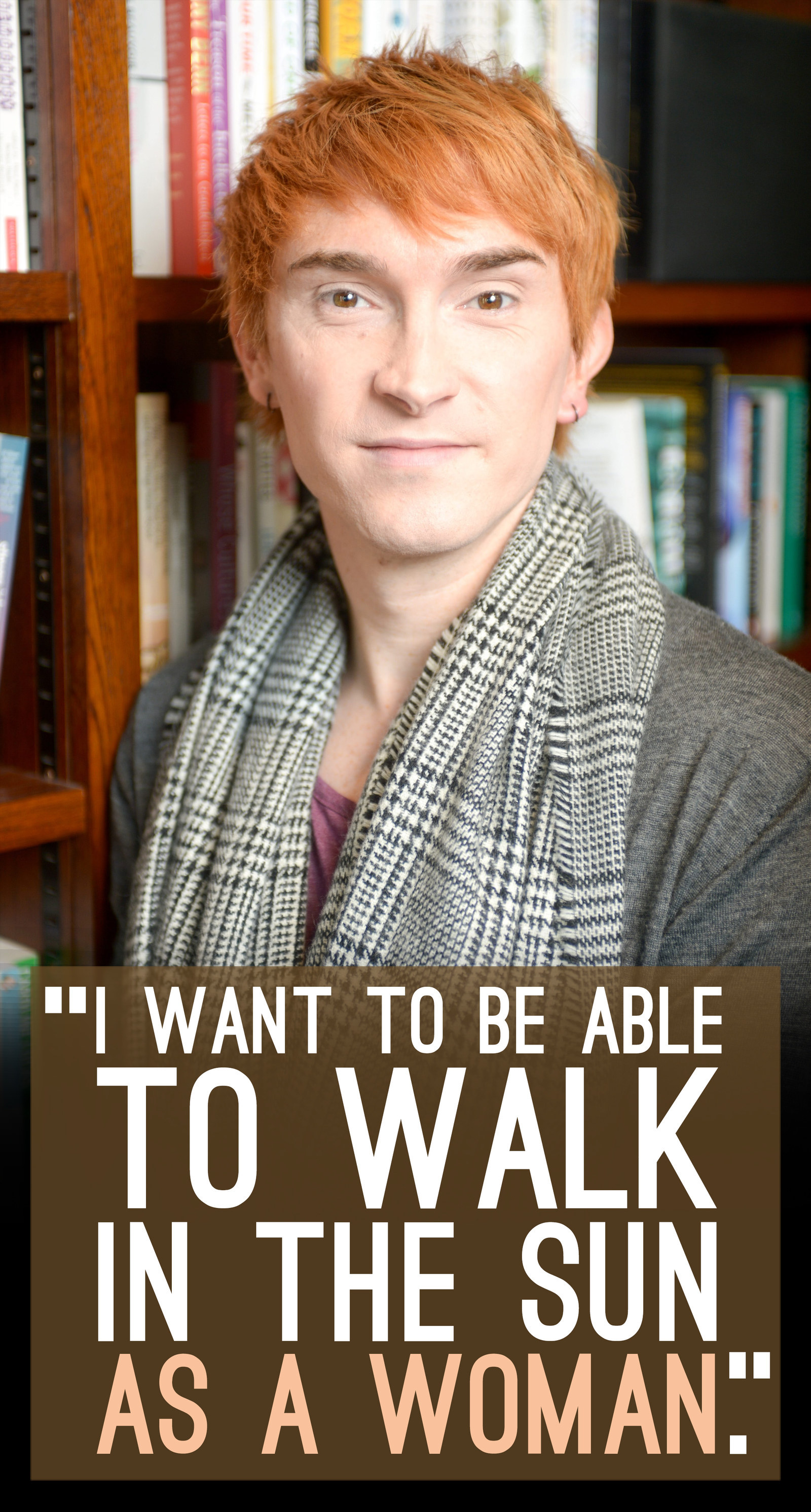

“I’m a trans woman and I’m about to start transitioning,” he says. His seven multi-award-winning books, including Hollow Pike, Say Her Name and the international bestseller This Book Is Gay, line up behind us on his desk, each bearing a name that will soon disappear: James Dawson. The male pronoun will be gone soon too, but for now he asks to be called “he” and referred to by his birth name.

“You wouldn’t call a butterfly a butterfly until it had hatched,” he says, wryly. His hair is a feathered pixie-cut, recently dyed the colour of pumpkin; his lacquered nails are black as crows.

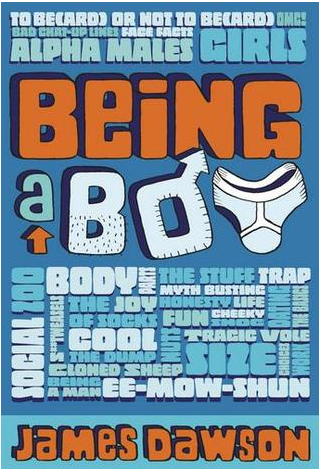

Just a few months ago, Dawson lost the hipster beard he’d grown to go with the muscles he spent years obsessively building and the tattoos he’d had branded on to him. He tried hard to be a man. He even wrote a book called Being a Boy. But, it transpires, after 30 years of trying – pretending – a lifetime of instincts rose up and shook him. “I’m not wasting any more time in the wrong gender,” he says. “So let’s get on with it.”

The urgency is not only personal. In a little more than four months, Dawson’s new book, Spot the Difference, will be in every primary and secondary school in Britain, as one of only two YA (young adult) books selected for World Book Day – a global celebration of books, endorsed by Unesco. As such, every schoolchild in the UK will be given a voucher to buy Dawson’s latest. He’ll be touring the country, going into schools, giving talks to thousands of kids. It will, he hopes, be just a few weeks into his hormonal transition.

No trans author has ever been given this platform; and in the UK, no YA author has ever come out as transgender before (in the US, several have, including Zac Brewer, Charlie Jane Anders, and Everett Maroon).

“I’d like to think in 2015 being trans is so mainstream now that it won’t be an issue,” says Dawson, “but sadly there will be people who will think it’s weird, and there is the worry that there will be a tabloid backlash around a ‘trans children’s writer’.” He pauses and looks up. “Mainly I’m just excited.”

On the opposite wall, above the fireplace, a painting of a Pierrot gazes at us: ruffles round the neck, a tear on the cheek, a painted mask over the face. As we talk, and Dawson’s past surfaces – a tale of disguise, suppression, and performance – the metaphor sings out.

Dawson was raised in Bingley, West Yorkshire, in the 1980s. He declines to reveal the precise year (“I’m a beautiful woman now,” he says jokingly, as if channelling an ageing diva. “We do not discuss our age.”) Bingley, he says, is “very white, very working-class, and very un-diverse”. The former mill town is famous for the Bradford and Bingley building society and for the serial killer Peter Sutcliffe, aka the Yorkshire Ripper. Dawson was not exactly in his element there.

It was clear at 3 years old that Dawson was not like other boys. “My alter ego was called Princess Susan,” he says, cross-legged on his couch, a multicoloured throw draped behind him. “I was really confused about why I wasn’t a girl. I was very much drawn to female characters: Daphne from Scooby-Doo, Sheila from Dungeons & Dragons, Teela from He-Man. I used to wear my mother’s golden bedspread like a cape.”

Dawson says he was always jealous of the particular kind of attention and gifts his sister received. He would play a game with the kids down the street called Boys and Girls. “I was always a girl,” he says. He would watch his mother, who worked in a factory, get ready on a Friday night.

“That ritual of her doing her nails, her makeup, her hair. I can’t smell hairspray without thinking of my mum — that Elnett haze.”

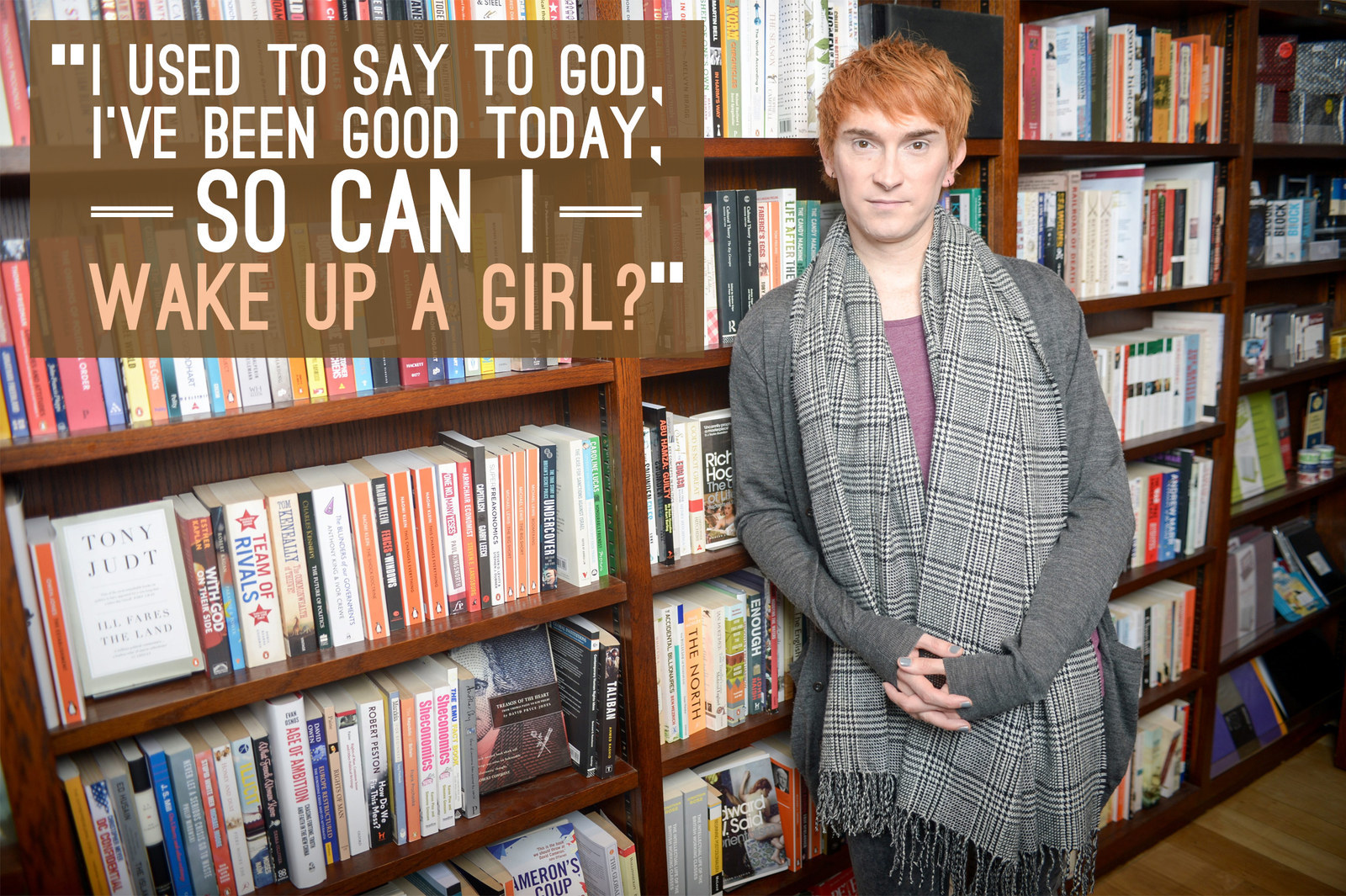

At night, Dawson would pray.

“I used to go to bed and bargain with God and say, ‘I’ve been good today, so can I wake up a girl?’” He looks out of the window. “There was always this parallel world that I imagined. It was the ‘what if I were a girl' world. I knew what I would look like. I knew what I would be doing. I knew what clothes I would wear.” On shopping trips he would spy outfits and think, “Alternate me would wear that.” He collected dolls.

“Around that time the adults around me started to worry about why I had those things,” he says. “Eventually my dad took all my Barbies away.” His father, a sales rep, attempted without success to entice Dawson into the worlds of football and fishing. Dawson’s alternative one, of dolls and dressing up, innocence and longing, would soon turn dark.

At secondary school, the other pupils started to ask Dawson, “Are you a girl?” One of the teachers called him “Dolly Dawson”. As adolescence emerged, the other children called him “gay”, and laughed.

“One boy used to drag me round by me ears,” he says, flatly. “My ears are wonky now; they weren’t wonky before.” Some of the other kids would throw chewing gum in his hair. “I’m lucky – I was never punched.” Nonetheless, it was horrible, he says – more horrible than he realised at the time. There was something else of which he wasn’t aware: “My parents thought about sending me to a psychologist. I don’t know what they hoped that would achieve.”

By then, Dawson had stopped dressing up, confined by the fear and shame bestowed upon boys who will not be boys. He couldn't, however, avoid his burgeoning feelings for men. His first crush was Dean Cain, who played Superman in Lois & Clark: The New Adventures of Superman. He knew nothing of transgender people – in the 1990s, he says, there were no role models accessible to a child in Yorkshire. Instead, he assessed his situation and came to a conclusion.

“Given that I had been told I was a boy and I knew that if you are a boy that fancies boys that makes you gay, that was the only alternative I could see.” And so, at 15, he claimed the label “gay”. “It answered a question, it made me feel like I didn’t have to marry a woman and live in a Barratt home. The problem was that the label just wasn’t the right one.”

Dawson speaks quickly, skipping over difficult memories, rarely pausing to engage with his own words. What was happening for him, internally, during that period of bullying and identifying as gay? He stops.

“At some point during school I decided I could either feel hurt or feel nothing,” he says, gazing at the magazines in front of him. “So I opted for nothing.”

When asked if there is a link between Dawson disconnecting emotionally as a teenager to then devoting his life to writing for that age group, he agrees hesitantly.

“I just never did my puberty. And as I transition I’m finally going to get to do the puberty I should have had. I’m obsessed with the idea of transformation –chrysalis periods – because I’ve never got out of the chrysalis.”

Shutting down at secondary school proved to be a crucial pivot in Dawson’s life.

“I swapped feelings for achievements,” he says, adding that he knew education would be his only escape to a different life. “I poured myself into goals and ambitions.”

Dawson got into university, started coming out as gay, and found like-minded friends. At 22, he became a teacher, moved to Brighton, and flung himself into the gay scene, performing in an electro-punk band. He started having relationships with men.

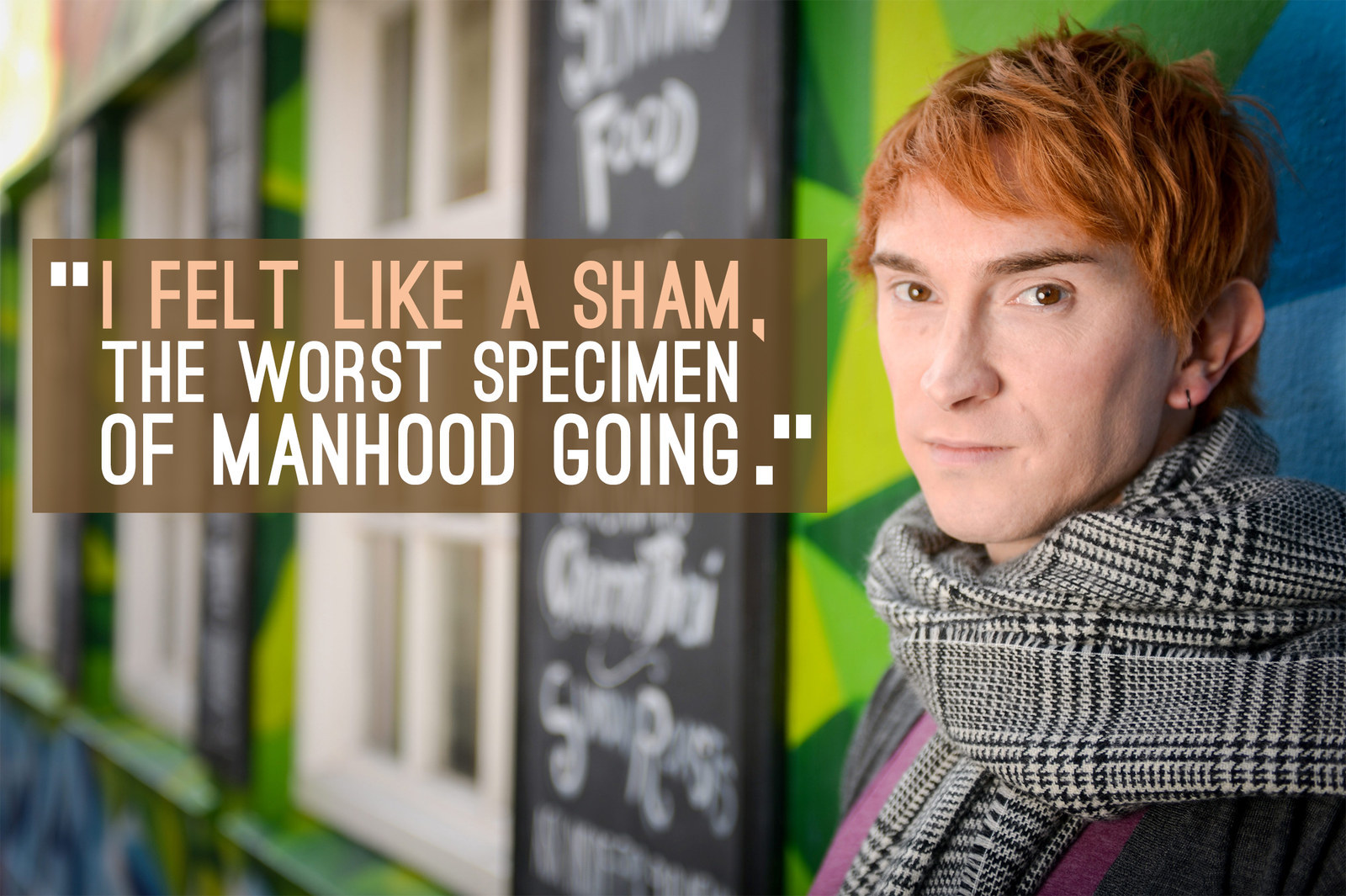

“But it always felt like roleplay,” he says. “And there was something inherently wrong with the dramas I was casting us in, because the issue was never them, the issue was me: I could never understand how they could love me, because I felt like a sham, the worst specimen of manhood going. I didn’t understand what they found attractive. There was always this thought: What do they even see in you? You’re just not a man. And they’re gay.”

This sense of inadequacy, combined with the fetishisation and expectation of masculinity on the gay scene, prompted Dawson to hit the gym endlessly. Sometimes he went twice a day.

“It wasn’t healthy,” he says. “I was firmly convinced I could weightlift my way out of femininity.

From 2012, Dawson’s books – including the aforementioned Hollow Pike, Cruel Summer, Under My Skin and Say Her Name – sold fast, being translated into multiple languages and garnering critical acclaim. His pithy, frank style resonated widely with young people, leading Patrick Ness, the celebrated author of A Monster Calls, to describe Dawson's latest work All of the Above – a teen romance – as "everything you'd want in a best friend: funny, rude and totally has your back."

Dawson could write young female and male characters with equal three-dimensional flare: the insecurities, the friendships, the sex, spots, and burning intensity of being a teenager, conjured with levity and precision. Dawson side-stepped into nonfiction, too: Being a Boy provided the ultimate guide to male puberty. And early next year sees the publication of another nonfiction title, Mind Your Head, exploring mental health issues in young people.

But there was one book that would change Dawson's life: This Book is Gay, a no-nonsense handbook for growing up as lesbian, gay, bi, or trans. While writing it, he was working part-time for First Story, an organisation that brings authors to schools in deprived areas. One day, in 2013, Dawson was giving a workshop in a south-London comprehensive when he met an 11-year-old called Charlie.

“She had decided in year 7 that she was going to start going to school as a girl,” he says. “She was so cool and smart and I just thought to myself, Imagine if that had been you, if you’d been able to have your whole life in the right gender. I realised, If she can do it in a Lambeth school, aged 11, you have no excuse at 30. None. You’ve got to confront this.”

From there, he says, his gender identity became clear through a succession of small realisations. “And it was a proper surprise that I wasn’t gay, was never gay, and was trans the whole way through,” he says, pausing, as if to evoke the penny dropping. “Damn.”

“There was a real sense of time wasted, and immediacy, like, You’re still relatively young, quick, get on with it.” He told a couple of friends. “They said, ‘Look at us, we’re an artsy crowd, you don’t need to go through a big medical transition!’"

He tried out being androgynous while in the electro-punk band and it wasn’t enough.

“I did all that with makeup and costumes – I would go out in a fur coat and eyeliner but I was still a boy called James and still male. It’s about fulfilment, fulfilling what I was always meant to be.”

Dawson eventually found the courage to go to a therapist specialising in sexuality and gender identity. The first session didn’t exactly play out as he expected.

“He said, ‘You’ll never be a woman; you’ll be a trans woman, it’s different. You’re never going to have a period, or a baby, or a fully functional vagina.’ I went home from that session so despondent, but I realise now he was doing good therapy because I had completely unrealistic expectations of the process, the waiting list, and the endurance test that transitioning is.” The therapist asked Dawson a question that took him six months to answer.

“He said, ‘How would you feel if you go through this whole transition and you’re still not satisfied?’ Because we had talked a lot about the fact that I’m never satisfied and it’s haunted my whole adult life.”

In the end, Dawson came to a conclusion and told himself the words that will define the rest of his life: “You’re definitely a woman.” But, he adds, “transitioning isn’t a magic wand; it isn’t Hogwarts. If I’m lonely now I’ll be lonely after I transition. If I’m unhappy now I’ll be unhappy after I’ve transitioned. The only thing that will have changed is my gender. My baggage is coming with me.”

Dawson went home to Bingley to tell his mother. She was, he says, worried he wouldn’t be able to find a boyfriend, but, along with his father, said, “Well if it makes you happy.”

“My mum and dad are quite unsurprised,” he says. “My sister thought I was being very brave. Trans people hear that a lot. It’s a shame we have to be brave.”

Dawson’s GP referred him to an NHS Gender Identity Clinic, and he’s hoping for his first appointment before Christmas in order to start taking hormones as soon as possible.

“Right now I’m a transitioning woman on a waiting list,” he says. He’s started buying women’s clothes and shoes, and experimenting with makeup – “lots of black eyeliner, boots, and leather” – and is considering facial feminisation procedures.

“I’m really worried about that first day I step outside head-to-toe, makeup, hair, clothes,” he says, pulling at his scoop-neck top. It is the first time he has sounded frightened.

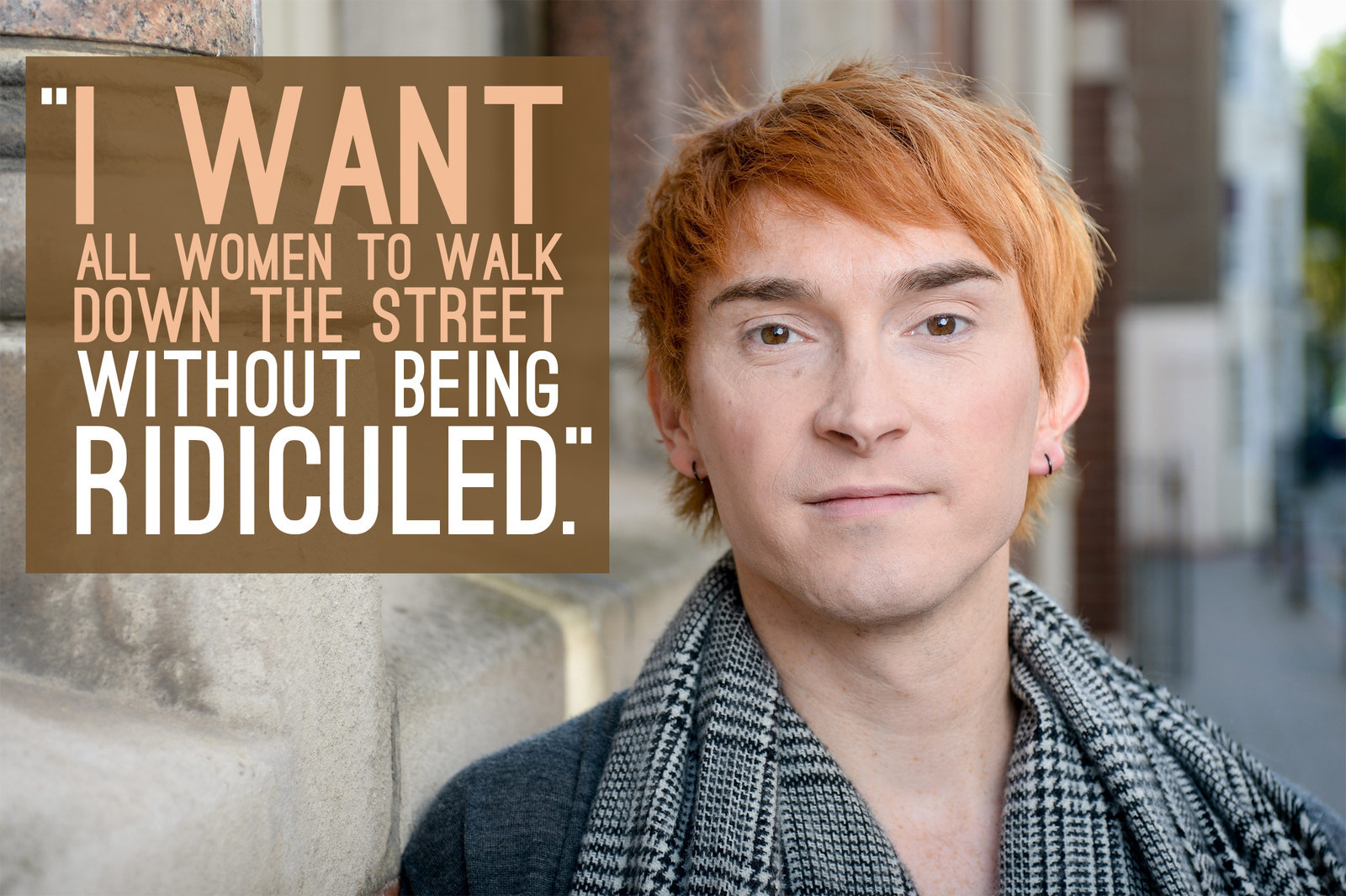

“This currency of passing [as a woman] is bollocks: We’re all women, we’re all trans women, and I want to get to a place where all women can walk down the street without being ridiculed. Because I’m becoming a woman I’m buying into a lot of bullshit that all women have to put up with – this idea that women are flawless, finished, retouched products who must never be seen looking a day over 30, or without their eyebrows drawn on, never mind a stray body hair.”

Dawson’s feminism kicked in further after deciding to hormonally transition. The day after he finally vowed to go forward with the process, he woke up the next morning and found himself thinking he couldn’t have a fried breakfast.

“Straightaway my mind knew I could not be too young or too thin. Where did that message come from?” he asks, knowing exactly where.

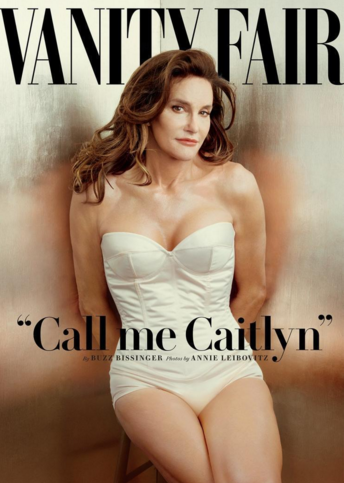

Part of Dawson’s motivation for disclosing his transition publicly is as a reaction to Caitlyn Jenner, whose ultra-glossy “reveal” on the cover of Vanity Fair was far removed from the experience of every other trans woman.

“It wasn’t achievable, because we’re not millionaires,” he says. “If I had billions you wouldn’t have seen me for dust. I’d have been at the best clinic in LA and I would have been sitting here right now with an entirely different body and wardrobe. At least now there isn’t a house in the Western world that isn’t aware of what a trans woman is, but the problem is, is that what people think a transition is like? That we vanish for two months and come back with a new face, hair, and an Annie Leibovitz cover spread? For most of us it’s slow and frustrating.”

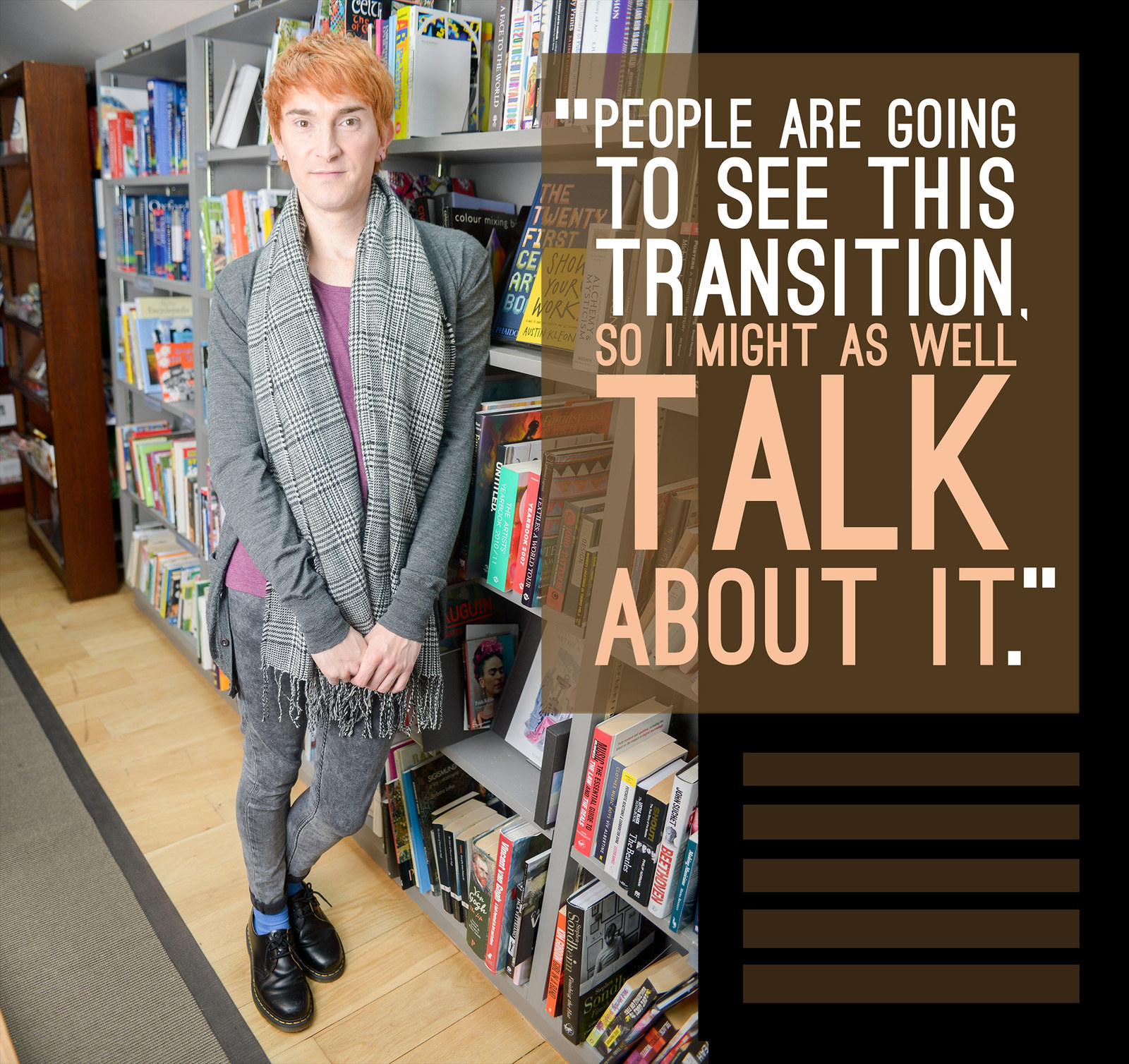

For Dawson, the marathon that is transitioning on the NHS will not only be long but public. His diary of professional engagements for 2016 is already filling up.

“People are going to see this transition,” he says, defiantly. “It’s going to look weird, my hair is going to look awful – there’s no way I can hide that so I might as well talk about it, write about it, and reveal it.” (He's currently in talks about documenting his transition for Attitude magazine.)

The practical considerations are piling up –when to change his passport, when to use the women’s toilet for the first time, how to negotiate relationships – but his priority is to set the transition in motion. There are the professional considerations, too, such as whether to change his name on already published works. At the moment he feels happy to publish new titles with his new name. He wants to wait until he is absolutely sure on the name before he reveals it.

Dawson’s publisher, Hot Key, has been supportive from the outset, he says. When he told people there the news, he had already been selected for World Book Day. “Their question was, ‘Where do you think you’ll be in your transition by next March, when World Book Day is?’ and I said, ‘Well, it will be well underway.'”

Ultimately, Dawson wants not only for his transformation to be swift, but for societal change to swift too, so that all trans people can come out and feel free.

“I hope that in a year or so I will be considered a woman and can go out as a heterosexual woman and date men and not have to dwell in specialist underground lairs,” he says. His eyes narrow, drifting off somewhere for a moment.

“I want to be able to walk in the sun as a woman.”