A young man stands at the edge of the Manchester ship canal. He steps forward, and in. The water, tepid from summer, rises up his shins, thighs. He begins to wade. He wants to vanish. Now he is up to his waist.

It is early afternoon at the end of August this year, days after another man injected him with seven times the dose of crystal methamphetamine he had agreed to take. Days after psychosis set in.

Minutes elapse. Two passers-by stop, spotting the unnatural sight. What are you doing? Do you need help? There is no response. They stretch out, clasping his arm and yanking him back to the path. The next day a psychiatric unit admits him – another young man, splintered from reality.

Three months later, and hundreds of miles away, I sit on his bed in London facing him. His name is Rob. He is handsome, smartly dressed, educated.

I want to know how he got there, and how so many more like him fall out of the world most of us recognise and into a hell most know nothing about, a glimpse of which recently reached the front pages.

The glimpse came from the trial of Stephen Port, last week convicted of the rape, overdosing, and murder of four young men – a serial killer whose weapons were the drugs used to heighten sex and, for a minority, to enact the worst of crimes.

Police will now re-examine the deaths of 58 other people from the drug GHB over the last few years. The question this raises is: What have they been missing?

Throughout the reports of the trial one word recurred again and again: chemsex. Uttered in increasingly wide circles, the term refers to men having sex with each other while imbibing, inhaling, or injecting (“slamming”) three principal drugs: crystal methamphetamine (aka crystal, meth, Tina), GHB (aka G), and mephedrone.

Combining sex and drugs is nothing new, but this particular trinity of substances – and their unique effects – entwining over the last few years, along with the contexts in which they are being taken, have given rise to a secret world now spilling out into public spaces: police stations, hospitals, psychiatric wards.

Chemsex can involve two men together in private, or many more at clubs or, more commonly, house parties. The meetings are usually arranged through websites or hookup apps – which dealers also use to sell their drugs – bringing men together who do not know each other. Sessions frequently last many hours, often several days.

Inhibitions and defences evaporate.

Throughout 2015 and 2016, amid a series of conversations I had socially with gay and bisexual men about chemsex, new, darker elements to this scene began to emerge; details from unconnected participants that mirrored each other – the same incidents, the same crimes, sometimes even the same culprits. Together they formed a picture: that beneath the surface reports about chemsex – the endless hedonism, the irresistibly intense sex – there is a much blacker sea, unmapped.

And so, during the Port trial, I returned to some of those men and contacted others, to document their experiences of the hidden side of chemsex. This process triggers almost unbearable questions about what is happening.

They describe wide-scale and systematic sexual violence, the deliberate drugging of vulnerable teenagers, the coaxing of impoverished men into a cloaked world of prostitution, frequent mental breakdowns from meth-induced psychoses, overdose victims routinely left to slip into comas, and a pile-up of sudden deaths.

Rob knows of seven people who have died in the last five weeks. Anthony, another interviewee, says he knows of four in the last week. He has already lost a close friend who picked up what he thought was a glass of water and drank it. It was GHB. “They took him to hospital and six hours later he was dead. His internal organs shut down one by one.”

Other chemsex users spoke of witnessing horrors so frequently that they appear routine.

“I’ve seen guys that have been awake for five days, and the end of their fingers have gone blue because they’ve lost all circulation to their extremities, but they’re still trying to have sex,” says Glenn.

“I’ve seen guys with scars all over their shoulders because they were on crystal meth and they were convinced they had something under their skin; I’ve seen people with huge burns on their face where they’ve dropped a Tina pipe on their face; I’ve seen people so paranoid that they’re ripped their whole kitchen out looking for a camera. I’ve seen people almost sexually assaulted and the only reason they weren’t was because I stopped it.”

“I’ve seen guys that have been awake for five days, and the end of their fingers have gone blue because they’ve lost all circulation to their extremities, but they’re still trying to have sex.”

Almost no one is coming forward to report incidents to police. And most are not seeking help from services that treat substance abuse or tackle sexual exploitation.

Two men warn me not to look too deeply. There is, they say, the potential for retribution from those who benefit – and profit – from the silence.

It takes hours for Rob to build up to describing the events that led to his immersion in the canal. Before then he has other stories. He begins by talking about what happens when chemsex sessions derail, much of which clusters around one word: consent. This does not pertain only to sex.

“When someone meets someone for sex but with the intention to harm, overdosing them is one way of doing that,” he says. On several occasions, he adds, “I’ve been given more than I agreed to take. There isn’t much you can do.”

He describes men injecting more crystal meth into his arms than he wanted, or pressurising him to take higher doses of GHB – a pressure that becomes easier to exert when judgement is already skewed by the chemicals’ effects.

“The difficulty with chemsex is that there is a very fine line between having a great time and things going wrong,” he says.

Indeed, the drug GHB (gamma-Hydroxybutyric acid), which is an anaesthetic that depresses the central nervous system, producing effects similar to both alcohol and ecstasy, is notorious for the minuscule window it provides between intoxication and overdose.

The tiniest increase in dose can render a user unconscious, often for hours on end. Overdoses are frequently accidental, or self-administered. But because GHB comes either in liquid form or a powder, it is also easily slipped into someone’s glass.

With sex under way and the drugs hitting brain receptors, sexual boundaries can dissipate or, Rob says, be disregarded. Domination role-play, for example, can descend uncontrollably.

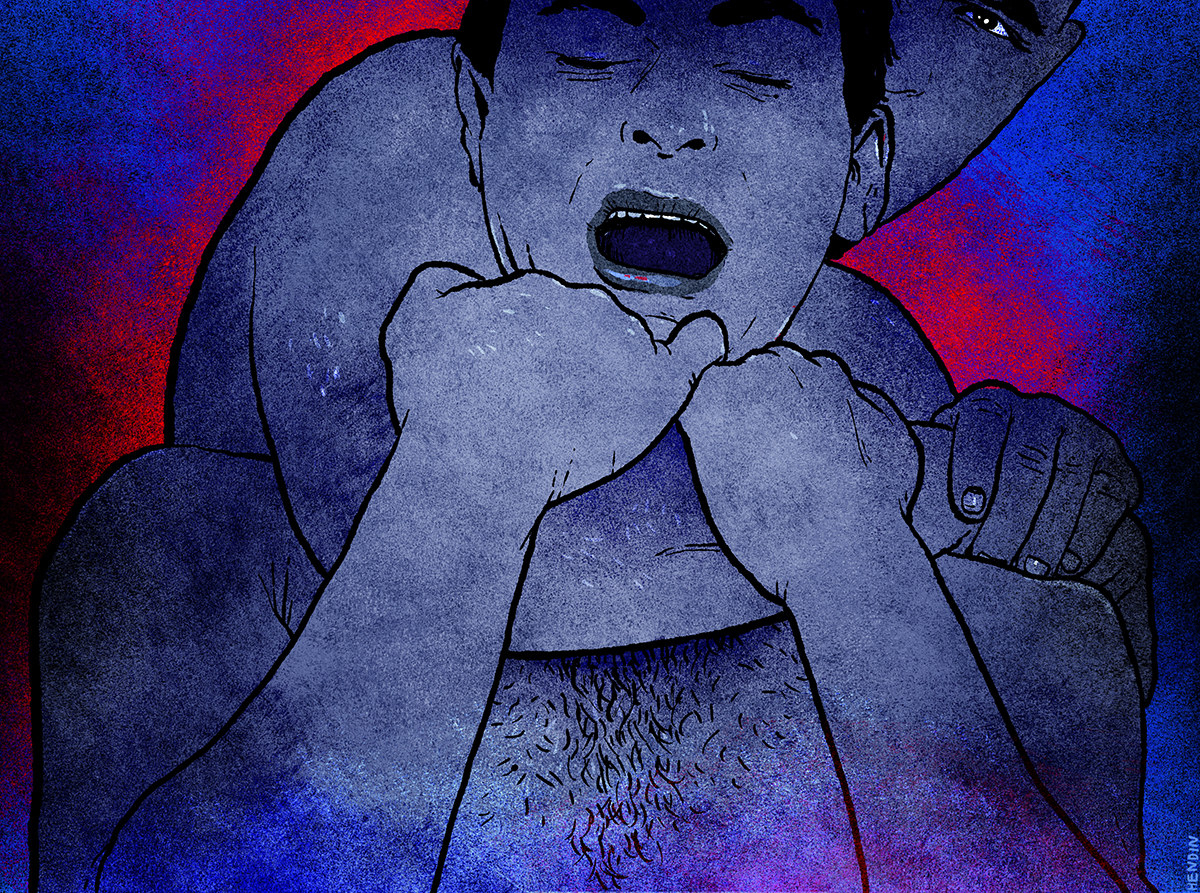

“I’ve let things happen for fear that if I didn’t…” he begins, widening his eyes to a glare to suggest the rest. “Strangulation is an obvious [example]. If you get gripped round the throat you start to think the worst: Is this going to be the one that kills you?”

On other occasions, what begins as standard slap ’n’ tickle has swerved beyond the agreed limits into punching, the pain of which is anaesthetised by the drugs.

“You don’t realise until you wake up the next morning and you’re black from head to foot on one side of your body,” he says. Rob talks a lot in the second person – you this, you that – when describing what has been done to him.

He thinks that some of the men who have administered overdoses to him – during which he has lost consciousness for hours – wanted him dead. A couple of them, he says, were angry and irritable when he woke up. He is only grateful that so far he has come round, and that on one occasion in 2011 he narrowly escaped the grips of Stephen Port.

“Some of the things they say will scare you. One said, ‘Would you like to be murdered while being fucked?’”

“We spoke online, but on the day I was meant to go to Barking [where Port lived] there was something that told me ‘this is not a good idea,’ so I decided to cancel.’”

With other men he only realised their intentions during a session, when it was too late. “Some of the things they say will scare you. One said, ‘Would you like to be murdered while being fucked?’”

Rob performs an exaggerated smile at this, to soften his words, but it conjures a grimace. He sits stooped on his bed, shoulders and neck in a C shape, as the light above him yellows his face. He does not seem to connect with what he is saying.

There is, however, a palpable frustration in him, that despite the danger, he feels unable to stop. He cannot enjoy vanilla sex, he says, and needs the drugs to disinhibit him. There is a sweet, shy geekiness to him, as well as a passivity – his past is daubed with bullying and depression.

Rob describes a man he met at a chemsex party, for whom he climbed into a sling – a harness suspended from the ceiling – in order that the man could have sex with him. The man, he says, had brought a young guy with him from a date earlier that day that hadn’t worked out.

“They didn’t fancy each other, so his enjoyment was to fuck me as hard as he could while making this boy stand next to him watching him. He was doing it to punish him, as if to say, ‘You could have got this but you weren’t good enough.’ I didn’t like the fact he was taunting him by using me. I wanted to get out,” he says.

There was another element to the scenario: verbal abuse, centred around the suggestion that the sex would make Rob HIV-positive. “He said, ‘I want you to be my poz bitch. You’ll never forget being pozzed up by me.’”

Young and inexperienced, Rob did not feel able to say anything. “I was not going to cause a scene,” he says, but “I was moving about to try and get him to stop, to hint that this was enough.” He did something else, too, while lying in the sling, with several other partygoers just a few feet away.

“I was waving my hand at the side, to the others sitting, [as if to] say, ‘Can you get me out of the sling?’ Nobody came. I knew I was just going to have to take it.”

None of what Rob describes is alien to others I interviewed. Glenn, who is in his late twenties, has all the outward markings of self-assurance: big voice, extrovert, tall, muscular. He now does outreach work in clubs to inform gay and bisexual men about sexual health and chemsex.

“I was always very safe and always used condoms,” he says about the period when he discovered the chemsex scene. “And then I went to a guy’s house and he overdosed me on G and I woke up and he was fucking me. That’s the time I got HIV.”

He had other experiences involving overdoses. “I went to a party and someone, who was off his face, gave me this drink and it had god knows how much G – he wanted to make me off my face or didn’t measure it properly – and I woke up in hospital, in intensive care, three days later, with my parents crying.”

"I went to a guy’s house and he overdosed me on G and I woke up and he was fucking me. That’s the time I got HIV.”

Anthony, who is in his thirties, talks quickly, passionately, and desperately wants the chemsex scene to change – for people to be helped. He says a friend of his has had threesomes with a couple on chemsex drugs and describes “one boyfriend getting jealous and putting the other under [making him unconscious] so he could have sex with my friend”.

Everyone I spoke to referred to overdoses happening at parties and people around them doing nothing.

“It’s a common story,” says Kyle, crossed-legged on a sofa in north London. Mid-twenties, with clothes draped over thin limbs, he has the insouciant air of an art student. “Someone going under on G and the guy hosting the party being like, ‘Oh he’s fine, just leave him.’ Not like, ‘Call an ambulance.’”

Two years ago, the after-club private parties in east London he attended started modulating into chemsex orgies in the small hours.

“It got so normalised: ‘Oh, he’s gone under.’ Someone would [he rolls his head and eyes back, mimicking someone passing out] and people would laugh about it, which is really fucked up. The lack of empathy that these drugs give people – and gave me – that’s the scariest thing.”

Some who overdose aren’t even fortunate enough to be left alone at the party. “I’ve heard stories of guys being thrown out the flat into a bin outside and being left to die,” says Glenn, who, like Kyle, sees these incidents as symptomatic of the twisted, inhumane states into which these drugs whip people.

Crystal meth, in particular, is a powerful stimulant – a class A drug known for its capacity to remove not only inhibitions but also, in the frenzy of the high, human kindness, all while accelerating sexual desire, energy, and, often, aggression.

It is not surprising to those who have experienced this kind of bacchanal, that sexual violence frequently enters the room. But even when it occurs while someone is still conscious, a chemically altered state can distort perception and awareness of what is happening.

“At that point when sexual assault happens, because you feel happy – high on drugs – you don’t think about it as a sexual assault,” says Paul Doyle, who went from being on the chemsex scene to setting up – as a drugs worker – Britain’s first residential chemsex unit. “So then a few days later it might start kicking in.”

At that stage, however, denial can kick back, in part fuelled by the mental disconnection while the assault was taking place. “That’s often a safety mechanism subconsciously,” says Doyle, explaining that this mixture of confusion, psychological defences, and disconnection can lead people to think: “I know I can’t consent legally because I’ve taken drugs but if I believe I’ve been sexually assaulted will anyone believe me?”

Kyle relates to this. “By some people’s definition I have been raped more than once,” he says. “But I would never define it as that in my head – it doesn’t feel like that.”

Legally, however, there is some clarity: One must have the mental capacity to consent, and consent can be withdrawn at any time. No one I interviewed, however, describes what they have been subjected to as a crime, or has reported it as such.

Kyle also describes a group dynamic at chemsex parties that discards standard social codes: “It was an unspoken thing that if you went under on G or weren’t aware of your surroundings and people had sex with you, you couldn’t really blame them for that because you put yourself in that situation.”

Rob’s depiction is somewhat darker still: that if there is someone who is disliked by others at a chemsex party, he may become a target, either for deliberate overdosing or “the alternative method: seeing how many people can shove their cocks up his arse, and that’s where the consent issue comes in. Does he want to do that? Or does he not? With all those chems no one is going to be able to say, ‘No, he said he didn’t want it.’ The others can say, ‘We thought he did.’ It’s very easy to pretend to be innocent.”

Amid this mess of victims being blamed, or blaming themselves, and mental fog about the events themselves, Doyle says there will be many people who only realise they have been a victim of a crime when they read details of the Stephen Port case and recognise what happened to them.

“It will open up memories just by that fact it’s being spoken about,” he says, adding that it will also mean that other people will only now realise that they have been a perpetrator.

“There are people I’ve worked with who have done things… and there’s a lot of guilt there,” he says. “There can be evil people who will do things regardless of narcotics, and then people simply under the influence of chemsex drugs which lower inhibitions.”

In Doyle’s experience working with people trying to leave the chemsex scene, about 1 in 5 have been sexually assaulted. Issues of consent also extend beyond drugs and sex. Several interviewees described being filmed during a chemsex encounter without their permission or even knowledge.

“He was broadcasting it live on the internet,” says Doyle. “I didn’t know who was watching it or even what site it was on; he didn’t ask me, it was only because I saw a webcam. I just didn’t expect to see a laptop there with a camera on his bedside table. I looked at the monitor and he was streaming it.”

A similar thing has happened to Anthony, he says. The second time he went to the house of a man hosting a chemsex party in east London “he was sat on the bed in the middle of all that was happening and he had his iPad on. There was a guy either side of him watching this porn. I stopped and looked over at the iPad and was like, ‘Oh that looks quite hot, what porn is that?’ It was me from the last time I was there.”

"I just didn’t expect to see a laptop there with a camera on his bedside table. I looked at the monitor and he was streaming it.”

On another occasion, it wasn’t being filmed that bothered Anthony, but what was about to take place on camera.

He was at a man’s flat, in a one-to-one chemsex session, with three webcams on. They had been having sex on G for several hours, he says, during which the man had become more aggressive, including slapping him. The man withdrew, told Anthony to go and shower, and asked him if he would wear a blindfold when he returned. “I was like, ‘I’m not really into it but I’ll give it a go.’”

When Anthony came out of the bathroom “there was this other guy in the living room”. The third man was just as surprised to see Anthony: They knew each other. Anthony also knew that the man was HIV-positive but refused to take medication. When medicated successfully, antiretroviral drugs prevent HIV from being transmittable sexually. Without them, the individual remains infectious.

Anthony realised what had happened: The host had invited the man round without showing him a face photo of who was there, and, Anthony believes, with the intention of getting him to infect Anthony.

“I was going to be put into a sling, blindfolded, off my face, and he had snuck the guy in while I was in the shower, to then breed me, unawares.”

Anthony, however, who exudes an air of impishness, saw the man and simply said, innocently, “Oh my god, what are you doing here?” The apparent plan had been foiled.

Although he is keen to emphasise that much of chemsex is fun, exciting, and sexually liberating, it is through Anthony that some of the sadder, socioeconomic factors emerge. He had come out of a long-term relationship when he ventured on to the chemsex scene in 2014. He had no job and nowhere to live.

“I ended up going from sex party to sex party for three weeks nonstop, just for somewhere to be,” he says. Anthony looks both boyish and knowing; an open face with been-there-done-that facial expressions. “I think there’s that huge element in London – a hidden homelessness thing.”

Kyle became homeless amid his chemsex usage, the drugs pressing what he calls the “fuck-it button”, where the mundane responsibilities of life, such as showing up for work, are jettisoned. “I just left my job, didn’t pay my rent for three months, and then obviously my landlord kicked me out,” he says. The graduate ended up back at his parents’ house, working in a café.

“I ended up going from sex party to sex party for three weeks nonstop, just for somewhere to be.”

Intersecting with this, says Anthony, is hidden prostitution. “There’s this grey area where people don’t identify as a sex worker – this unspoken thing of ‘drugs is the currency we’re using for me to do things to you that you’re only doing for the drugs.’”

As well as people who otherwise would not sell themselves being paid with drugs, straightforward money-for-sex transactions arise, especially for chemsex users in poverty, like Anthony.

“I got into a conversation [on a dating app] with a guy asking if I wanted to come over and he would pay me £600 to host a sex party,” he says. The man was a banker. “I said, ‘No, I’m not an escort.’ This went on for an hour and then I was just like, ‘fuck it’. So he sent a Mercedes to pick me up. I went to this luxurious penthouse apartment.”

“He got us so high,” he says. “He didn’t like escorts, and this is telling: He liked picking on people who he knew would need the cash but who aren’t seasoned enough to know the tricks [of the trade].”

In this scenario, every notion of personal agency is removed. “There are certain things, which when sober you would be empowered enough to say no to, but when you’re high and someone is pushing for that and you’re at his pleasure and it’s his drugs, then you do end up doing them.”

He sets the scene of that particular party: “This fat old dude with loads of money – he was the only one wearing a T-shirt because he was so fat, but no pants – was going round shovelling drugs and G into people in the hope that someone would go a bit squiffy and he could swoop in. The guys were basically bait.”

The host would subject young men to a particular line of questioning that disturbed Anthony. “He would say, ‘Tell me about the first time you had sex,’ which obviously would be when you’re younger, but he would push the boundaries of that and ask about my family and my nephews and be like, ‘Does your nephew ever touch your dick?’”

“The guys were basically bait.”

Chemsex prostitution became a regular occurrence for Anthony: “I would be chilling out [on drugs] for two days and then some old guy on Grindr would want to join the party and pay £200 for half an hour.”

By then, he was also drug-running for a major dealer. “I would get my drugs for free and I would be taking drugs to a client, so there was that symbiosis,” he explains.

Anthony’s descent into this world might seem extreme but to talk to him – articulate, funny – is to be confronted with how normalised such experiences are for many. Most stories conveyed by these men are told with matter-of-fact detachment, not out of a breezy disregard for what they have endured, but in the manner of someone simply attempting to cope with it.

In the end, says Glenn, the sinister side of chemsex is the final product of a process that begins with one thing: “Loneliness. What you’ve got with this scene is people trying to not be lonely any more, but drugs turn them into really nasty people so it perpetuates the whole situation.”

Other interviewees offer further explanations: internalised homophobia destroying people’s self-esteem, rejection from families prompting a desperate need for connection, a desire for total escape to avoid pain in general, depression, body dysmorphia forcing the need for inhibitions to be removed – a vast, invisible mental health crisis. Or, like with Kyle, it is a steady drift, often unintentionally, from social fun into unhinged darkness.

Anthony, for example, talks about seeing young, naïve guys arrive at a party equipped with boundaries and good intentions. “Then you see them six hours later being fucked bareback by four people.”

He says chemsex offered “intimacy without investment” after his relationship ended. “If you’re emotionally hungry and the only thing you’re reaching is that, that’s really fucking sad.” And the cost can be greater than most could imagine. The consequences for mental health, in particular, are dire.

“I got sectioned for four months,” says Doyle, who describes depression, exhaustion, and hallucinations. Kyle knows three people on the chemsex scene who have had breakdowns. The mere fact of staying awake for several days is enough to trigger one, he says.

“I did crystal meth and after day one at the party I was at home freaking out for four days, not eating, not sleeping. I didn’t talk to anyone, I stared at the wall; it was insane. I remember seeing that the soles of my feet were bleeding just from walking up and down my bedroom.” He says he’s never told anyone that story.

Paranoia, along with psychosis detaching the individual from reality, swamps people for hours, days, even weeks. Anthony says he went on a 12-hour coach journey because he thought the police were following him. On other occasions he’s wandered the streets for 18 hours, after which, “You don’t know where you’ve been, what you’ve done, or what was real.”

Doyle has also suffered dramatically on a physical level. “I got diabetes because the amount of drugs had damaged my pancreas,” he says. “And I found out I had liver cancer.” He has finally gone into remission but through his work sees myriad health problems with his clients, particularly viruses such as HIV and hepatitis C. Almost invariably these come from intravenous drug use and condomless sex, but in a few rare cases, diagnoses have arisen from the most extreme practices scarcely ever seen in treatment facilities.

“You don’t know where you’ve been, what you’ve done, or what was real.”

“Blood-swapping,” he says, describing it as a practice involving the injection of a drug, letting some blood out and injecting that into the other person. “It used to be taboo. I would never have had clients five years ago telling me they did it. It is a fetish for some people, a way of connecting.”

It should be stressed that most gay and bisexual men are not involved in chemsex. This is a minority within a minority, with the more extreme activities concerning yet another even smaller minority within that. There is also a scarcity of reliable, large-sample statistics on chemsex drugs usage, although the 2014 England Gay Men’s Sex Survey offers a useful indication.

Based on a sample of 15,360, 8.4% had taken crystal meth at some point, 12.5% had taken GHB, and 16.5% had taken mephedrone. When asked about drug usage in the last four weeks, these figures drop to 2%, 3.2%, and 5.3% respectively. Beyond this, anecdotal evidence from users and drug workers fills in some of the gaps.

The age range, says Doyle, is unprecedented, with people using chemsex drugs ranging from 16-year-old boys up to “people in their seventies and eighties. For the first time we’ve got drugs hitting our whole adult age group.” He suspects from conversations with fellow drug workers that underage boys are doing it, too.

We also know from drug workers and charities that it is a national issue but with epicentres in London, Brighton, and Manchester. We know too that accessing meth, G, and mephedrone is quick and easy through dating apps – in one day during the research for this story, I switched on Grindr and without me contacting anyone, two dealers sent me messages offering their products. Grindr did not respond to my request for a comment on this.

The challenge for the police and the justice system now is to encourage people to come forward. But many I interviewed were afraid, beyond not being believed or of police homophobia, that if they reported being assaulted while under the influence, they would be investigated for drugs offences.

The Metropolitan police told me, “Our priority would be to investigate the sexual offense allegation” and that it is not a criminal offence to have drugs in your system.

But a spokesperson for the Crown Prosecution Service directed me to the Code for Crown Prosecutors, in which there is one key line regarding drug users as witnesses to a crime: “The more serious the offence, the more likely the witness…will be prosecuted.”

Given that supplying drugs is the greater offence than possession, that should reassure victims. However, simply passing a needle or a glass containing G – routine in chemsex – to another partygoer could constitute supply.

The silence surrounding what is happening, agreed the interviewees, is compounded by a paucity of services available. There is some specialist help for those suffering from problems caused by chemsex, at sexual health clinics such as 56 Dean Street in central London and with some LGBT charities such as Galop, London Friend, and the addiction organisation Antidote. But these can never cater to the sorts of numbers that might need it.

The day Paul Doyle comes to see me, he had received some news about his residential unit in Cornwall, the only one of its kind: “I had a phone call this morning to tell me it won’t be staying open much longer.” By January it will be gone.

Meanwhile, says Doyle, drug counsellors across Britain continue to phone him, needing information about chemsex because they know so little.

There is one final detail that he describes, about where on the body chemsex users are often injecting the drugs, which reveals more than it should. “Stabbing it in their groin, their feet,” he says. “Places that are dangerous. Places that can’t be seen.”

But it was what was in the needle that led Rob into the canal that Saturday afternoon. Two days before, he had invited a man who he met online over to his house. “His only interest was to get the chems inside me. There was no foreplay, just, ‘I want your arm, let’s get this into you.’” Rob agreed to take half a milligram of crystal meth.

But the man, whom Rob describes as much bigger than him, kept pushing the syringe. “When the 3.5mg went in my whole brain started…he could tell that really hit me. I was scared. His clothes came off as quickly as he possibly could and said, ‘Time to get up inside you, mate, you’re never going to forget this.’”

The man started putting his hands round Rob's throat while penetrating him, he says. “I fought this as if to say, ‘That’s too much.’ I hadn’t gone under enough for him to do anything without me belting out, so he said, ‘Ugh, I can’t do anything with you.’” The man stopped and got up. Rob was shaking but eventually the man went to leave. His parting words, says Rob, were, “I’ll turn up somewhere where you least expect me to.”

It was only after the man left that Rob looked around his bedroom – where we sit now – and saw what cemented his belief that the man had wanted him dead. “There were two full syringes of crystal left.”

“You think doors are opening and people are coming in through the window. You think BBC TV are filming you.”

That evening, the psychosis began to rage. “I was seeing friends, family, everyone, walk past this door. You think doors are opening and people are coming in through the window. You think BBC TV are filming you.” The following day he sat in London’s Euston station “debating whether to sign into a mental hospital”. Instead, he boarded a train to Manchester and stayed with a friend, but the next morning his mental state started spiralling downwards.

“I’m seeing all sorts of things, people taunting me saying, ‘We knew we couldn’t trust you.’ I went round Manchester, wandering the streets, lost. I went out towards the motorway. I thought, Let’s get out of here, let’s just die. I managed to get back into the city centre and towards the canal. I’ve never started the suicide process before. I started putting one foot in the canal and then another…”

The two men who grabbed him from the canal put him in an Uber back to the house of his friend who later took him to A&E. After being transferred back to London, Rob spent five days at the Maudsley psychiatric hospital. It took another month for the visions, the paranoia, and the psychosis to abate.

Rob has been referred to a psychiatrist and is under the supervision of his local mental health team, but his biggest fear now is not what happens to him, but to others.

“There is a whole generation growing up in their late teens who won’t have had proper sex or consent education, who are naïve and who are vulnerable,” he says. “My worry is they will find themselves having gone through what I and lots more my age have gone through – but no one is willing to talk about it.”

Some names have been changed to protect the identities of participants.