If you suspect people are grumpier in the winter months and in the mornings, then Twitter might just prove you right.

A new study by the University of Bristol has looked at 800 million tweets and found people posted more positive things in the spring and summer months, when the days are longer.

"Circadian Mood Variations in Twitter Content," published in December in the Brain and Neuroscience Advances journal, surveyed anonymised tweets from the 54 largest towns and cities in the UK every 10 minutes for four years, to investigate how social media could provide insight into mental wellbeing throughout the year.

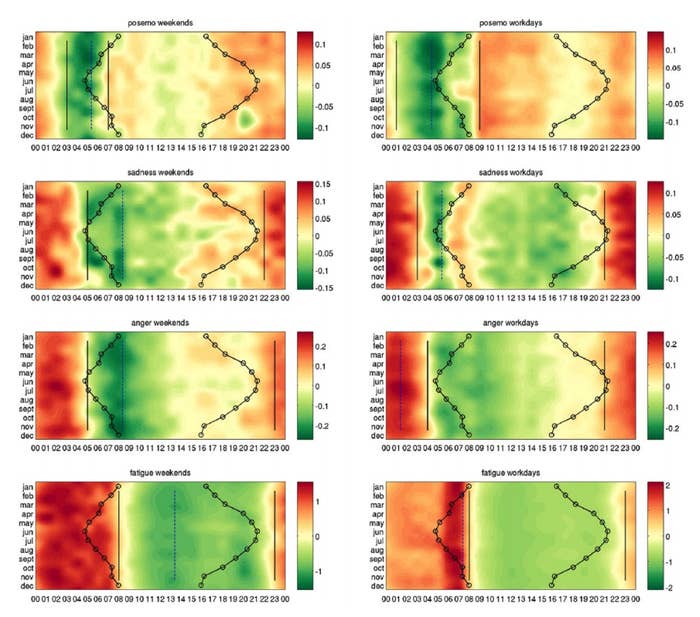

The study established a trend in the number of negative tweets people in the UK send at different points in the day and throughout the year. Unsurprisingly, they appeared to be grumpier in the mornings.

The study showed that the number of negative tweets – ones that mention being angry and tired – was stable across weekdays and weekends and over the seasons. But the number of positive emotions expressed grew higher as the days grew longer.

There are reasons to be a bit wary of studies linking word use on social media to emotion, as Pete Etchells, a psychologist at Bath Spa University, points out: “There’s an underlying assumption that if I tweet ‘I’m having a great day, I love life’, it’s a real expression of my feelings.

“But there’s not a lot of big studies showing that, so you should take these studies with a pinch of salt.” The paper doesn’t show that the changing times of sunrise cause the differing patterns of mood, just that they change at the same times. However, Etchells said that the paper shows that careful use of Twitter data can tell us new and interesting things.

The researchers found evidence that chimed with previous studies of seasonal affective disorder, where people suffer low moods as a result of receiving less contact with sunlight in dark winter months, which can conflict with their circadian rhythm, a 24-hour internal cycle that governs how we sleep and eat. Previous studies on this have relied on retrospective questionnaires on a much smaller scale.

Nello Cristianini, a professor of artificial intelligence at the University of Bristol and one of the authors of the study, told BuzzFeed News: “This is about the daily cycle of people's emotions – while these may change from person to person and from moment to moment, there is a baseline daily cycle that becomes visible when you average over many people and many many days.

“But it is also about establishing how useful Twitter data can be to measure shifts in collective mood. We have a way to measure changes in public mood, measured over many people. Slowly we are learning how to use social media to understand these average/collective movements in public sentiment.”

Etchells, who was not involved in the study, said that it was interesting in its own right, but he was most excited by how it utilised mass public data.

“It’s a good paper,” he told BuzzFeed News. “It’s not about Twitter at all, really. What it’s about is looking at whether mood varies over time in the day, and whether that changes depending on which season you’re in, using a very big data set – Twitter – to do it.”

It was interesting, he said, that while tweets including fatigue-related words seem to peak in the mornings, the time they peak isn’t affected by the time of year, even though sunset and sunrise change with the seasons. “You’d expect fatigue to change across the year,” he said, “but it doesn’t. Fatigue and anger seem to be season-invariant.

“Positive emotion and sadness, you do see some relation to season; sadness seems to get later in the day in June and July,” Etchells said.

“I see this paper as proof of principle,” he said. The authors took steps to avoid various problems with the data, such as that words like “happy” will crop up a lot around certain times of year as people tweet “happy Christmas” or similar things.

“They do some neat stats to avoid problems like that,” Etchells said. “The findings aren’t exactly groundbreaking – we tweet that we’re tired in the morning – but that’s not the point. The techniques are clever and have been used well, so it’s showing that this stuff works.”