Dean Mitchell lives in his own version of paradise. But not for much longer.

Nestled in ancient Sussex woodland a few hundred yards from a main road leading south to Hastings is what the 39-year-old calls his hobbit house. It has no running water or mains electricity and appears to have been carved out of the landscape around it. It’s covered in moss and vegetation; birds nest above its doorway. It looks like it’s been there forever.

Mitchell, rolling a joint as he sits beside his crackling fire, explains how he built the house single-handedly over two weeks, three years ago, after buying the quarter-acre plot of land for £7,000. The breakup of his marriage had left him with nowhere to live and sent him into a deep depression.

In a few weeks’ time, the local council will order some bulldozers to demolish his idyll. While it’s his land, Mitchell never asked for planning permission and the council has been fighting him through the courts since 2015 to get him to take the house down. In July the High Court finally put an end to the matter by granting Wealden District Council an injunction to force its removal.

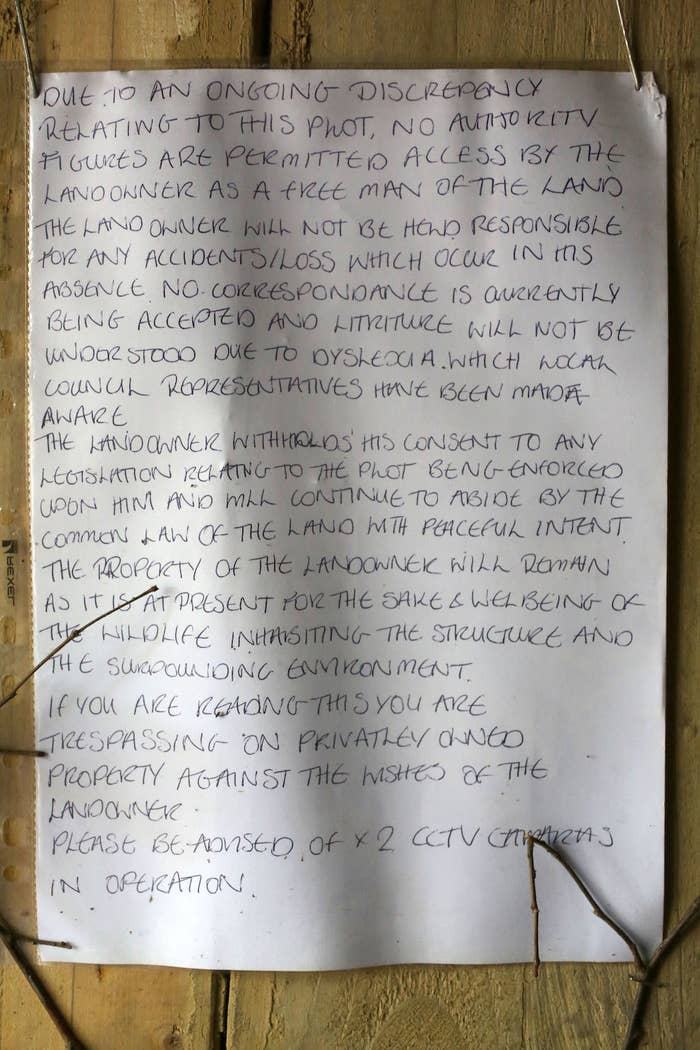

Mitchell didn’t fight his case in court – he says his dyslexia stops him from reading the court papers. But more importantly, he considers himself a “freeman on the land”, an obscure term with roots in the US’s anti-government, libertarian movement of the 1970s, used to describe people who believe they are not bound by law as determined by parliament, or any law they have not consented to. It’s Mitchell’s land, his rules, and at least while he's there he is not bound by any man-made law, he says.

He’s not alone: Stories of freemen, who frustrate court hearings with strange babble about the Magna Carta and maritime law, occasionally percolate through the legal community and social media, where Facebook groups such as “Practical Lawful Dissent” attract thousands of followers.

But who are these freemen, who sometimes refer to themselves as part of a lawful rebellion against the legal control of citizens’ lives, and where does their ideology come from? Is this a subculture movement built on a conspiracy theory? Or are they making an important point about an individual’s rights and how we are governed by the state?

“I was happily married, I had a house in Hastings, I had two kids, a 14-year-old and an 8-year-old. And she just decided that was it – obviously people fall out of love, I understand that. So we went through the divorce and I moved into my workshop in the garden for three weeks,” says Mitchell.

He ended up with about £15,000 from the sale of the family house in his hometown of Hastings and spent that on his quarter-acre site and the building materials to construct the hobbit house.

The turning point was when, already feeling suicidal as a result of his broken marriage, he suffered a slipped disc in his back. He was offered treatment, but only if he went to drug rehabilitation because of his regular use of magic mushrooms and cannabis. When he refused, a doctor told him: “Then there’s nothing I can do for you.”

This was the moment Mitchell checked out of mainstream society. “That’s when I decided. I’ve paid my taxes, I’ve worked hard all my life, and this is how society’s paid me back? I thought, Right, that’s it, no – I’m going to make a stand,’” he says.

Having planned to kill himself, Mitchell tearfully explains, he then visited a church to ask for forgiveness. The sermon convinced him that suicide was wrong.

Then came the hobbit house. It’s a small but impressive structure, completely in keeping with the natural environment. Wood-carved mushrooms lie around the site. Mitchell works two to three days a week making things like this for paying clients, for which he pays tax, he’s keen to point out. He has held parties here but says he has always turned the music down when asked. He has a good relationship with his neighbour, a cattle farmer.

Mitchell says he didn’t attend that court hearing because, as well as the difficulties with his dyslexia, the summons notice said the date was “to be confirmed”, signalling to him that it wasn’t set in stone. Fundamentally, however, he simply doesn’t think the court has any jurisdiction over him.

“To me there are no rules. As long I don’t do no wrong,” he says as his dog bounds through the trees, chasing after sticks. “I don’t feel like I’m bound by the law. If a policeman come up here, he’s on my land. I’m smoking marijuana, I’m taking magic mushrooms, and yes, I’m breaking the law but I’m not causing no harm.

“I feel people should be able to live how they want without being told what to do.”

A spokesperson for Wealden District Council said: “This enforcement action against an unauthorised dwelling in woodland has been taking place since February 2015. Throughout this time we have strived to make Mr Mitchell aware of his situation and offer him assistance.

“His appeal in January 2016 resulted in a 10-month extension to the deadline for removing the construction. This has been ignored. We welcome the decision by the Mr Justice Holroyde this July. We have allowed Mr Mitchell a further three months in which to dismantle the wooden construction.”

But what made Mitchell come the conclusion that as a freeman he was not bound by the law?

“The thing that got me more into this was when someone turned round and told me about birth certificates. You’re born into this world, you’re given a birth certificate, it’s got a code on it. You have this code all your life, and if you took that number into a stockbroker’s market he would tell you how much you’ve earned throughout your life and how much taxes you’ve earned.

“So basically they are banding you. And I don’t want to be banded. It’s like a bird being born. A bird doesn’t get told what to do, it just lives its life. That’s what I’m doing.”

This is common trope of freeman ideology: that what we think passes for identity is actually a construct. As freeman sites and forums would have it, your actual name and identity is a work of fiction created for the convenience of the state, which would like to control you. It’s only through this invented persona, the theory goes, that you can be made to follow man-made law. Hence why some freemen refer to themselves as “[first name] of the family [surname]” or add “commonly known as” to their titles, to point out the difference between their real and “fictional” names.

Mark McKenzie, 54, told Manchester magistrates’ court in May that he did not have to pay any council tax because he is a freeman who is “independent of government jurisdiction and holds the archaic belief that all statute law is contractual and therefore only applicable if an individual consents to it.”

He was sentenced to 40 days in prison and asked to pay the £7,000 in council tax he owes on his Moss Side house.

The same month, Oliver Pinnock, 36, a professional lightweight boxer from Leigh-on-Sea in Essex, was sentenced to 25 days in prison for the same offence, and told to settle his £875.44 debt with Southend Council.

He tells BuzzFeed News that in fact does not identify as a freeman, although he does believe that he is not bound by laws that came after the Magna Carta (the Great Charter) in 1215.

"I discovered an article in the Telegraph from 2001 that quite clearly stated that article 61 of Magna Carta 1215 had been invoked under the correct protocols of British constitutional law," he says.

"The Queen was petitioned and made a reply. The more I looked at this, the more I realised we were illegally joined to the EU against our bill of rights and Magna Carta, which is a binding contract between sovereign peoples and the monarchy."

The charter was invoked before parliament was established, he says, therefore any man-made laws are in essence null and void.

Freemen base much of their ideology around Magna Carta, the treaty that was designed to make peace between King John and rebellious English nobles. Mythology has surrounded this charter for centuries and it has become a global symbol of individual liberty against despotism, even though almost all of its content has been repealed or annulled over time.

Article 61 of the charter is often cited as proof that English citizens can opt out of abiding by law by statute - although, as historians and sceptics have pointed out, this article was only in use for three months and specifically referred to curtailing the power of King John and 25 barons, not the general populace.

Though it is illegal to film or take photographs in court, YouTube has several videos showing freemen baffling magistrates and judges with their interpretation of ancient legal codes and their refusal to accept the authority of the court.

An independent barrister, who is frequently briefed by the Crown Prosecution Service and who asked not to be named, occasionally sees such cases in court and has prosecuted two so-called freemen in the last two years.

“They are generally pretty difficult to deal with. Both people I prosecuted refused to recognise the court and refused to have any constructive discussion with me,” he says.

“Both were charged with relatively minor driving offences. When asked to identify themselves in court, they typically answer with something along the lines of ‘John X, agent for the fictional legal personality Mr X’ and then attempt to make various arguments about the court not having jurisdiction because they have not consented to the legal contract of the law.

“Personally I cannot see any prospect of a ’freeman’ argument succeeding. None of their concepts have ever been upheld and the whole belief comes out of an erroneous concept – that one can opt out of statute law as if it were a contract.”

Both of the cases the barrister prosecuted ended in convictions. In one, which was heard at crown court, the defendant was sent to the cells for a few hours for contempt of court due to his obstructive approach.

A famous case in Canada, a divorce hearing in Alberta in 2012, set out much of the history – and flaws – of the freeman movement and its neighbouring ideologies. The husband against whom the wife was filing declared that he was a freeman and therefore not bound by any ruling of the court and did not have to pay any more in divorce settlements.

"For the record, I, Dennis Larry Meads, and for the record a child of the almighty God Jehovah, and not a child of the state," he said.

In his ruling, the judge came up with a useful phrase to describe this kind of "vexatious" tactic: The organised pseudo-legal commercial argument (OPCA).

Summing up the case, the judge said: "To repeat myself, the OPCA arguments he has advanced have no effect or meaning in Canadian law. They offer him no rights, no indemnities, and certainly not a pot of gold or silver to call his own."

Whether it’s effective or not, that doesn’t seem to stop people believing it.

“The law, everyone should abide by it. There are essentially the Ten Commandments, cause no harm – common law. But the legal system, the statutes are only binding on you if you consent to them,” says Dave Murphy, who posts YouTube videos to the Allegedly Dave channel, which has 22,000 subscribers and more than 3 million views to date.

“One of the tricks they use is to ask you if you understand. What’s really happening is that you think the policeman is speaking to you in English but he’s actually using the language of legalese, which looks and sounds like English but it’s not. When you say you understand the words coming out of his mouth, but what you’re actually saying is ‘I accept to be bound by this.’”

Murphy is a high-profile freeman who is often cited as something of an authority in lawful rebellion/freeman circles. Aside from this, Murphy believes the Earth is flat and recommends drinking urine as a way to alleviate the effects of asthma and nerve damage. He was working across the Hudson River from the World Trade Center on 11 September 2001 and watched the attacks happen. He would later become a firm believer in the “deception” behind the official story of 9/11.

In 2009, having given up a lucrative computer programming career in the US, he attempted to start the Freeman League – an autonomous collective of like-minded people. The group began camping on a stretch of land near Grantham, Lincolnshire, and just like with Mitchell’s hobbit house, the local council put a swift and complete stop to their plans to build a self-sufficient village.

A series of widely shared YouTube videos from 2012 show Murphy – at great length – being stopped by a police officer while driving a convertible Mercedes. He refuses to give over his identification or insurance details.

After much discussion and confusion, he is taken to a local police station and arrested for not cooperating with police – he kept moving his fingers as officers attempted to take his prints. He spent six days in prison on remand and was told by a judge that that in itself was punishment enough. He never got the car back.

Murphy claims that because he was never charged with failing to provide identification or insurance, the police generated the obstruction charge as a way to stop him “asking some very awkward questions about people’s right to travel” during a court case.

But didn’t he lose the car because he wasn’t following the law governing motor vehicles?

“It was actually stolen from me,” he says. “How can the police take something from you without due process of law? Unless you go in front of a judge and a jury and it’s found that you’ve broken the law, how can you be punished?

“The police aren’t lawyers, they’re not judge and jury – how can they confiscate things off you before any wrongdoing has been established? We’re talking about a dictatorship of criminals. We’ve just been brainwashed.”

And also like Mitchell, Murphy says his “awakening” came around the same time as his divorce from the mother of his two children.

“Part of my awakening and questioning the world was questioning my marriage. Just like pulling at the threads of your life, I pulled at the threads of my marriage and it fell apart. If one partner wakes up and sees the world different and the other doesn’t, there’s an awful lot of strain that comes into the relationship.”

Both men’s stories suggest that such outsiders rebelling against the mainstream are doing so as much for personal reasons as wider political ones.

Sometimes, in rare cases, whether by design or accident, freeman strategies do apparently have the intended effect.

Trevor Hill, 58, from Derbyshire, claims he hasn’t paid council tax for years. There is no law, he says, that compels people to pay council tax nor any legal framework to force people to pay it. (Under section 47 of the Council Tax (Administration and Enforcement) Regulations Act 1992 nonpayment carries a maximum three-month prison sentence.)

In March 2015, Hill, along with another man, Simon Henry, appeared at Chesterfield magistrates’ court having been served a liability notice for failing to pay council tax.

Henry refused the magistrate’s request for him to take off his hat and turn off his phone. “This is my thought, consciousness, and religion and you cannot deny me these rights,” he told the court. Hill said he refused to give the court his consent to continue. According to a press report, he was led out of court while referring to his rights as a freeman on the land. They were two of 484 people the court was chasing for nonpayment of council tax at the time.

“With me I just completely rejected their authority to deal with a civil debt in a criminal court. They have no jurisdiction,” Hill says now, more than two years on. “Every letter I’ve sent to the council had been ignored. And to this day I haven’t paid my council tax.”

Hill phoned the police while stood in the dock: “I refused to leave and then I phoned the police, because the magistrate has failed to give me their oath and that’s against the law. I said: ‘They are breaking the law and I would like them arrested.’

“They told me to put my phone away and I said they had no authority, because I was a human being and they had decided to be persons. I was the highest-ranking person there, or human.”

Hill explains that a “person” is a legal entity or a fiction created purely for jurisprudence. “I don’t want to be a legal fiction, I want to be a human,” he says. Again, like so many freemen, he refers to birth certificates as proof of this.

Hill doesn’t refuse to obey all laws – he works as a driver and accepts that road safety legislation is necessary – and he claims that all he is asking for from the council is a breakdown of what his taxes are being spent on before he will agree to pay. He is essentially a small-state conservative worried about governments wasting resources. Why, he asks, can’t he pay the private company that empties his bins directly?

Asked where he first found the freeman ideology, his answer is telling and explains how the idea has travelled from North America to the UK: “I think the internet opened our eyes to a lot of this. Before the internet you had to go to the library and read all this. But now it’s at your fingertips. And everyone has a smartphone or a computer at home and it’s opened up this world of information.”

According to J.J. McNab, an expert on anti-government extremism in America, Freeman ideology has its roots in the Posse Comitatus (“force of the country”) movement of the 1960s and 1970s, which refused to acknowledge US law or taxes. While these ideas went dormant for a time, they reappeared in the sovereign citizen movement of the 2000s, which saw American, Canadian, and Australian patriots declare themselves exempt from all government statute.

In the 1980s the so-called redemption movement, largely based on the thinking of white supremacist Roger Elvick, popularised the idea that birth certificates had a financial value attached to them.

But in the end, whatever rebels may say, more often than not the law wins.

Mr Justice Holroyde, in giving judgment on Mitchell’s hobbit house, praised the builder’s “considerable skill in building the structure”.

“He has produced a letter, which confirms his own assertion that he has been able to do useful work in clearing parts of the woodland and in seeking to deter fly-tippers,” he said.

“He has, however, done all this in breach of the planning control which aims to protect and benefit the public as a whole and which applies to everyone – even those who, like Mr Mitchell, declare themselves not to be bound by the legislation and not to consent to its application to them.”