Soon after the Grenfell Tower fire came the anger, then the questions. Now victims’ families and survivors want answers.

The tragedy has posed a long list of urgent questions about the block’s refurbishment project and the type of materials used, about what this means for fire safety in the 4,000 other residential towers across the country, and, most pressingly, about how at least 80 men, women, and children died in their flats, on stairwells, or after jumping from windows as fire engulfed their homes.

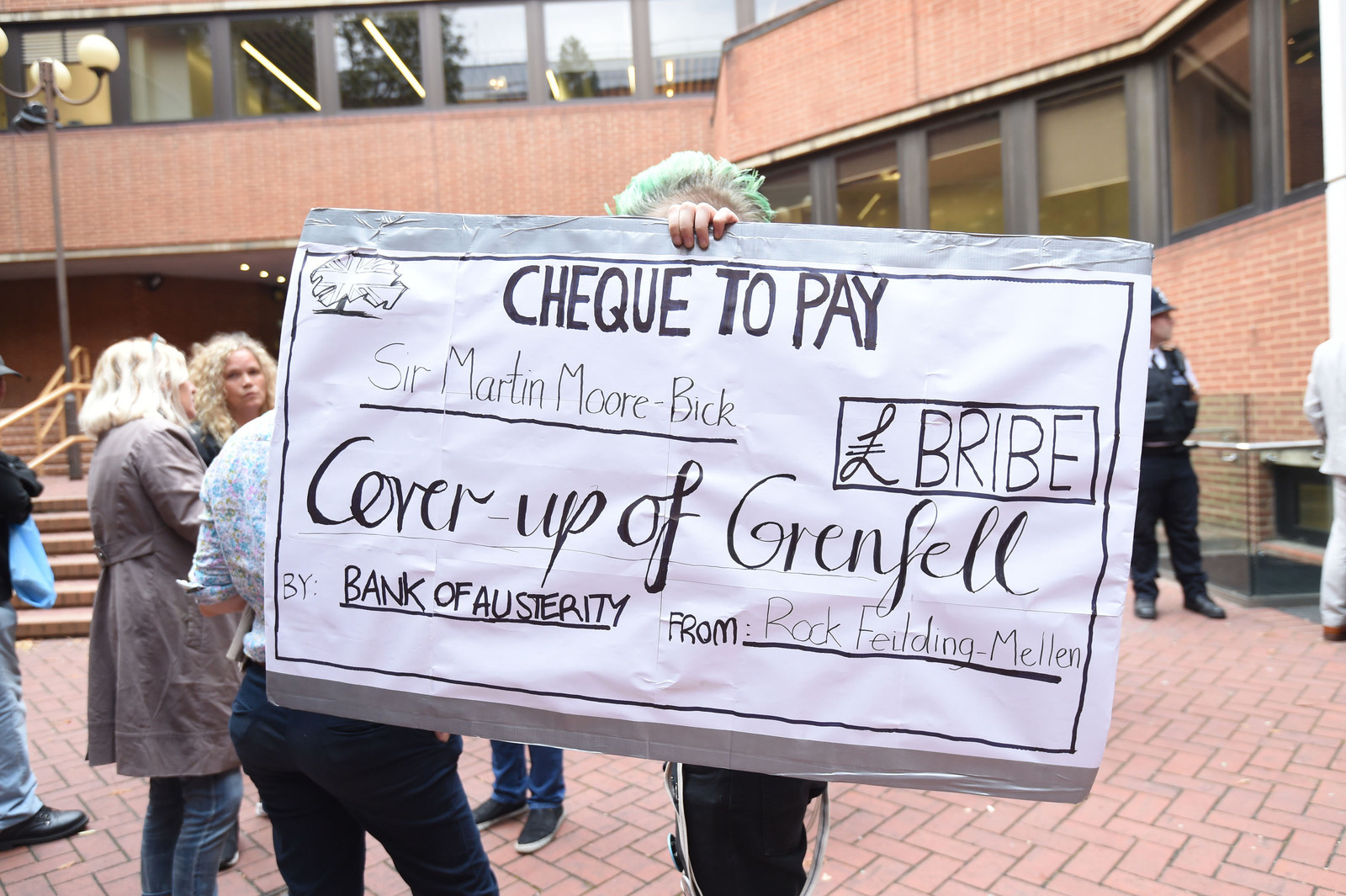

Now, one month from the hasty announcement of a public inquiry, to be chaired by retired Court of Appeal judge Sir Martin Moore-Bick, a debate rages over what shape it should take, what its terms of reference should be, who should take part in it, and whether the judge chosen to chair the arduous and complex procedure is the right man for the job.

One London MP, David Lammy, called for corporate manslaughter charges immediately after the fire. Graffiti and murals seen around the site of the tower in north Kensington have said the same, many directing their anger at the local council, which owned the building. The frustration that more hasn’t been done to bring those responsible to justice is palpable.

But how can this process win the trust of a wary and sceptical community and avoid becoming, as some have predicted, a whitewash or cover-up?

BuzzFeed News spoke to three barristers who have acted in some of the UK’s most famous and controversial inquiries to ask how this one can avoid the mistakes of the past and gain the confidence of those who have lost their homes and their loved ones, who worry that the inquiry won’t uncover the truth of what happened.

“They’re right to think [the inquiry may not uncover the truth] because that’s precisely what will happen unless they force the authorities to conduct a full, independent, effective inquiry,” said Pete Weatherby QC, of Garden Court North Chambers, who represented 22 of the Hillsborough families at the 2016 inquest and has acted in many public inquiries.

“That’s the clear lesson of Hillsborough, that ultimately after a judicial inquiry and a failed first inquest and multiple other legal proceedings such as judicial reviews, all of them failed. And 25 years later the families succeeded simply because they campaigned so tirelessly and hadn’t given up until they forced the government of the day to do something.”

The original Hillsborough inquest in March 1991 concluded that Liverpool fans had contributed to the chain of events that caused the deaths of 96 people – which Weatherby described as “probably the biggest miscarriage of justice in UK history”.

Last year’s inquest, 27 years on from the incident, completely exonerated the fans of any responsibility and ruled that the 96 were unlawfully killed. A criminal investigation into Hillsborough continues.

“The Grenfell victims and survivors will suffer the same fate unless they get a grip of it and are provided with a means to get a grip of it,” Weatherby said. “That means having proper lawyers who know what they are doing; it requires the proper legal avenues being crossed in the appropriate way.”

Things didn’t start well for Moore-Bick.

After he was announced as the inquiry chair on 29 June, newspapers and Grenfell families groups seized on a 2014 case in the Court of Appeal in which Moore-Bick ruled that a social housing tenant in Westminster, a single mother of five children, could be relocated to Milton Keynes, some 50 miles away.

The unease was compounded by Moore-Bick’s comments when he visited the scene of the Grenfell fire and spoke to survivors and witnesses on the day of his appointment.

This was a chance to build trust, but he told reporters that he had been asked to carry out a narrow inquiry that would not investigate wider issues surrounding fire safety in tall towers. The inquiry would, he warned, answer only basic questions such as how the fire started.

“I’m well aware that residents want a much broader investigation,” he said. “Whether my inquiry is the right way in which to achieve that, I’m more doubtful. There may be other ways in which that desire for an investigation can be satisfied.”

The government defended Moore-Bick and on 5 July a public consultation on the inquiry’s terms of reference was launched; the extended deadline is now 28 July. This is what victims’ groups were asking for, but the damage had already been done.

Things got worse for Moore-Bick on 7 July, when he was heckled and faced some tough questions during a three-hour meeting of the Lancaster West Residents Association, which represents those who live on the estate where the remains of Grenfell Tower stand.

Earlier that week, local residents and MPs had questioned whether a senior judge would struggle to understand the lives of working-class social housing tenants, mostly from ethnic minorities. The Labour MP for Kensington, Emma Dent Coad, said the retired judge was a “technocrat” who lacked the “credibility” to carry out the inquiry.

Moore-Bick told the meeting: “I can’t do any more than assure that I know what it is to be impartial. I’ve been a judge for 20 years and I give you my word that I will look into this matter to the very best of my abilities and find the facts as I see them from the evidence.

“If I can’t satisfy you because you have some preconception about me as a person then that’s up to you.”

Responding to a heckler who told him not to “get personal”, he replied: “Well I’m not getting personal – but you don’t respect me, because you say the government has appointed me to do a hatchet job.”

One resident countered that the inquiry wasn’t a hatchet job but could end up being a whitewash, like the Taylor report into the Hillsborough disaster.

Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn has since led calls for the process to be split into two parts: one that investigates the immediate causes of the fire and a second that look in broader terms at the problem of fire safety in tall towers nationally.

So how can Moore-Bick and this process win people’s trust?

One possible option is to appoint a team or a panel of advisers that represents the interests of the community and adds expert knowledge of fire safety and social housing. This had a profound effect on the outcome of the 1999 inquiry into the death of London teenager Stephen Lawrence, which produced a report, by Sir William Macpherson, the presiding judge, that found the Metropolitan Police to be “institutionally racist”.

Imran Khan, the lawyer who represented the Lawrence family during that inquiry, told BuzzFeed News that this was not just desirable, but essential.

“If this inquiry is going to succeed in terms of the confidence of the community, Moore-Bick has to have people on that panel who can give him the inside knowledge on what went wrong and how things work,” he said.

“In Macpherson we had Bishop [John] Sentamu, we had an ex-police officer, Thomas Cook, we had [doctor and anti-racism campaigner] Richard Stone, and I know with conversations that I’ve had with [Macpherson] since that they played a very significant part in influencing his thinking in terms of explaining the minutiae of how communities operated, the culture, the issues.

“Some reports have said there are calls for someone from within the community to be appointed – I don’t have any difficulties with that. Therefore it’s not that Moore-Bick isn’t going to make the final decision but at least he will have someone on the inside, in his ear, explaining things that he might not know about.

“If Moore-Bick does say something that sounds like a cover-up then you would hope the advisers would be brave enough to say ‘No, that’s wrong.’”

Despite repeated calls for Moore-Bick to stand down, legal experts do not think this inquiry would benefit from a change of leadership.

Adam Wagner, a barrister at One Crown Office Row who has acted in several large-scale public inquiries, including the one called after the Mid Staffordshire NHS scandal in the late 2000s, said that as much as people might not like Moore-Bick personally, the scale of the inquiry requires someone with his experience.

“The reason judges are pretty much the best people to choose for them is because ultimately an inquiry is going to be incredibly evidence-heavy. If I think back to the ones that I’ve been involved in, you’re talking hundreds of thousands of pages of documents and hundreds of witnesses over the course of a year or two years.

“To handle that amount of evidence and then write a report which is hundreds of pages long, that is the skill of a judge. And a good judge is really good at that.”

Wagner added that the public’s mistrust of inquiries is part of a wider trend that has nothing to do with Moore-Bick.

“You can’t forget that May herself has created the situation with the botched child abuse inquiry where she is directly responsible for undermining people’s confidence in the government’s ability to appoint a chair to an inquiry, and I think that the chickens are coming home to roost on this,” he said.

“People now assume that this person is unfit to lead until proven otherwise, which is a high presumption to get around.”

Pete Weatherby pointed out that there was initial scepticism about the choice of judge in the Hillsborough inquest in 2016 – Sir John Goldring, now retired – but the hearing produced a series of rulings that vindicated the families’ long fight for justice.

“There have been some very obvious, correct criticisms of [Moore-Bick] – he’s from that very narrow band of society that senior judges are from and of course there was that case that’s been reported which, on the face of it, does seem to make him not a great choice.

“But I would say that you do need a chair of some clout and therefore some of the other criticisms are perhaps going too far. The people who are saying ‘get rid of him’ need to say who they would like.

“Using Hillsborough as an example, we had another senior just-about-to-retire judge, Justice Goldring – none of us know much about him, he’d been a quiet judge throughout his career. He did a decent job and it was because he was assisted greatly by particularly the families’ representatives.

“The sort of ‘Oh my god, he’s an elderly white man from Oxbridge’ and whatever else he is – wake up and look at the reality, because you’re going to be hard-pressed to find someone who doesn’t fit that description. Scandalously, there aren’t many.”

Similarly, there was intense scrutiny over the choice of Macpherson to run the Lawrence inquiry. So much so that Imran Khan and others went to the then-home secretary, Jack Straw, to seek assurances. Khan doesn’t see intense scrutiny of judges running similar inquiries as a bad thing.

“We said ‘Hang on, Macpherson has a really terrible record on immigration cases.’ We thought he was not an appropriate individual to be dealing with an issue of institutional racism, given that he seemed to have an approach of rejecting lots of applications for asylum in this country,” he said.

“We wanted to say ‘We’re testing you, we’re keeping an eye on you. And the reason we’ve gone to the home secretary to challenge your position as the chair is because you’ve got a history and you’ve got to prove to us that we are mistaken and that your history is not going to affect what you’re likely to do.’

“Certainly from the TV coverage it looks like some of the [Grenfell] survivors are putting their marker down, because of the concerns they have about [Moore-Bick’s] history, and I think that’s absolutely right.”

In the end, Khan said, Macpherson’s rarified background may have actually helped the inquiry reach such strong conclusions.

“One of the good things that comes from lawyers like Moore-Bick is that they are from very different backgrounds. Macpherson was from a military background and he had no idea [about] race.

“When that [report] came out, he came out very much in favour of the criticisms and because of his background he didn’t feel afraid to make those criticisms and go out on a limb. That’s the background of some of these judges who come from that environment where if they see something they say it and they have no fear – there’s no political baggage, no sense of having to be accommodating to all parties.”

What Moore-Bick could do, however, according to Weatherby, is set the right tone in his dealings with the survivors and victims’ families.

“I think that [saying it would be a narrow inquiry] was such a faux pas that I think he is on the back foot now and he’s got to recover some ground. I think it’s a very bad mistake to go to any group of victims or survivors of a disaster of this scale and effectively say ‘trust me, I’ll sort this out.’

“I think that’s the wrong approach. I can tell you that with my 22 families at Hillsborough, I said I knew they’d had a train of lawyers and worthy people, judges and whoever else, come to them down the years and say ‘trust me, I’ve arrived and I’m going to sort it out.’ I’m wasn’t going to say that to them, and I didn’t.

“I said ‘I’m just going to get on with the job and if you don’t like the way I’m doing it then you must get rid of me.’ That was my approach. It’s not quite so straightforward with a judge – they have to be independent. He needs to turn up and say to them that they are at the centre of the inquiry.”

Khan agreed that a “legalistic” promise to simply follow the evidence and be impartial wouldn’t set the right tone.

“Moore-Bick has to say ‘Right, you have questioned me and now I’m going to deliver the goods.’ He has to see it in that fashion rather than in a resentful way,” he said. “During the Lawrence inquiry we had very senior police officers who rather than put critics at a distance instead brought them closer and said ‘Tell me what I’m doing wrong, tell me how I should be doing things.’”

Some Grenfell victims’ groups have argued that an inquest – where the cause of death would ultimately be decided by a jury – would be more effective in holding those responsible to account. But an inquiry has distinct advantages: The chair can issue an interim report, which is expected from Moore-Bick this year, and the terms of reference can be set to whatever the chair wants and be updated over time.

For Weatherby, the best chance of getting the outcome the families want will come from setting the terms as wide as possible. The inquiry into Lawrence's death simply said it would investigate “matters arising from the death of Stephen Lawrence”.

It is incorrect, said Weatherby, that the families of victims and survivors won’t be allowed to ask questions during the inquiry. It’s not an automatic right, but it does happen quite often, through people’s legal counsel. “I’ve just finished a four-month public inquiry and, believe me, I asked a lot of questions on behalf of the family,” he said.

“In a simple, straightforward public inquiry, it may be that the family wouldn’t ask questions, but with anything complex it would be impossible to have an effective public inquiry if they didn’t, so that’s not really an issue.”

The dangers associated with getting this process wrong and losing the trust of the affected community are huge. The outcome could be that the families refuse to take part altogether.

“He needs to say that he will involve [the survivors and victims’ families] to the utmost and he will conduct to the best of his ability not only an independent judicial statutory inquiry but one which is effective and will deal with as many of the relevant issues as is possible,” said Weatherby.

“Unless he says things like that, he will not gain the confidence of the survivors and there is a real chance – and this is only a guess – that they will not take part. Ultimately that’s a big issue. I don’t have any inside knowledge, but there will be voices saying ‘What’s the point here? This is a whitewash.’ And there are many examples of whitewashes in public inquiries. The survivors may well say ‘We’re not playing.’

“I’m not saying that would be right or wrong. I’m saying Moore-Bick runs that risk unless he gets a grip here. He needs to get a grip with the families and he needs to do it publicly.”