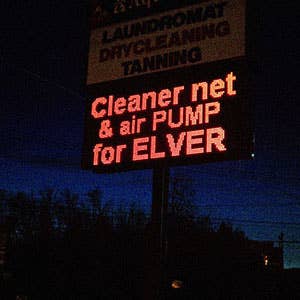

High Street in Ellsworth, a busy four-lane road lined with a Denny's, a McDonald's, an L.L. Bean outlet, and a Sun360 tanning salon, leads to Mount Desert Island and Acadia National Park. Beyond the strip malls and lobster pounds, further down east, are scarlet-hued blueberry barrens and miles of unbroken fog. Drive from southern Maine in the summer and you're bound to sit in Ellsworth traffic. Guidebooks claim the regional identity of the city has been stripped away, but at 3 a.m. the morning I arrived, a sign flashed outside the pet store in the cold night air: Cleaner Net & Air Pump For ELVER.

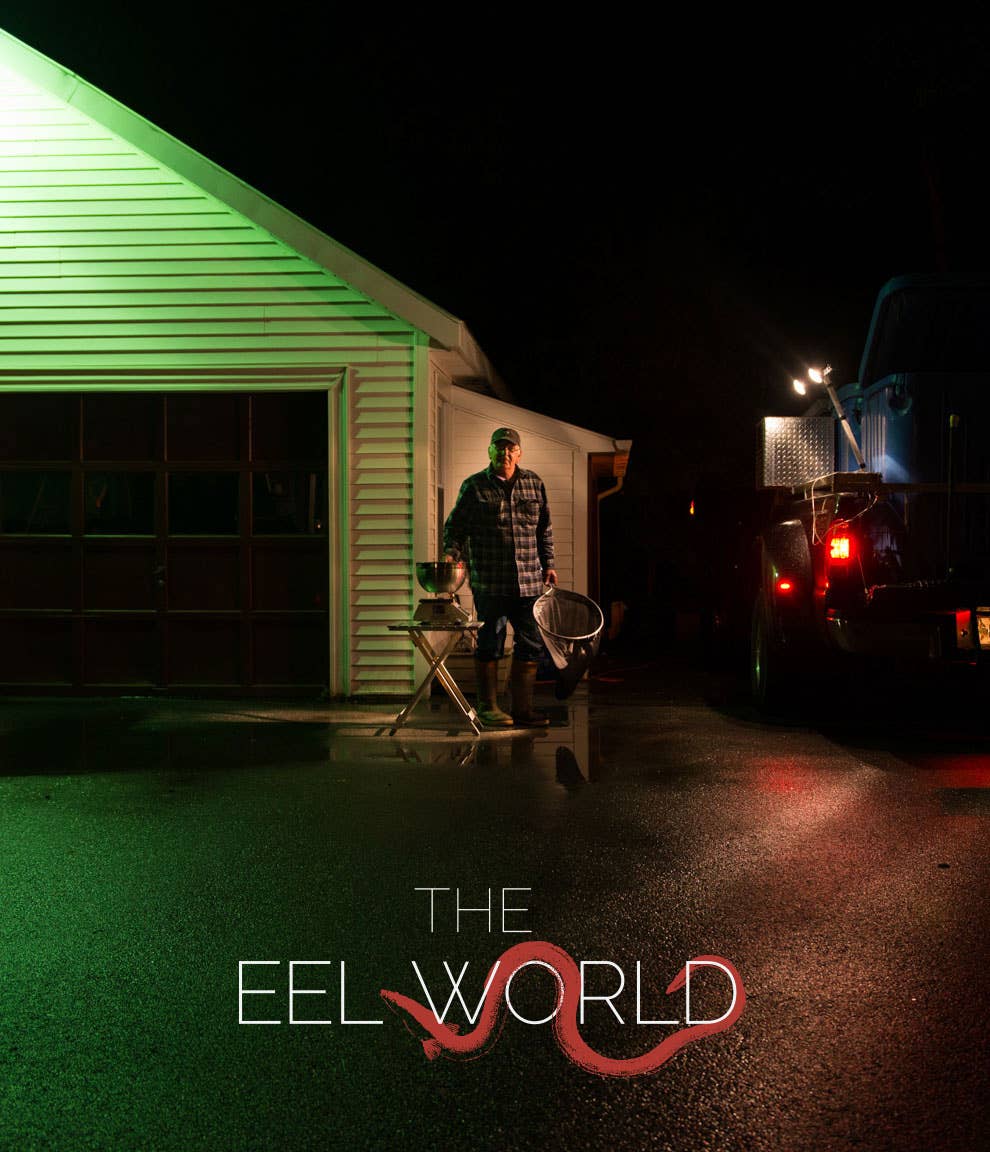

Behind Jasper's Motel and Restaurant, a yellow extension cord snaked through the window of Room 27 and connected to a 110-volt bubbler pumping oxygen into a tank of elvers on the back of a Ford Super Duty, or, as its license plate says, EEL WAGN. This is Bill Sheldon's truck. He's an affable, clean-shaven guy, aged 67, with glasses and an LED light clipped to the brim of his hat. In 2012, he paid his fishermen $12 million for elvers (about a third of the estimated $40 million paid out in Maine over the season) and, for a couple weeks this spring, the elver kingpin holed up at Jasper's Motel with a half million dollars in cash. The best runs and the best money too, he said, arrived on dark, moonless, rainy nights.

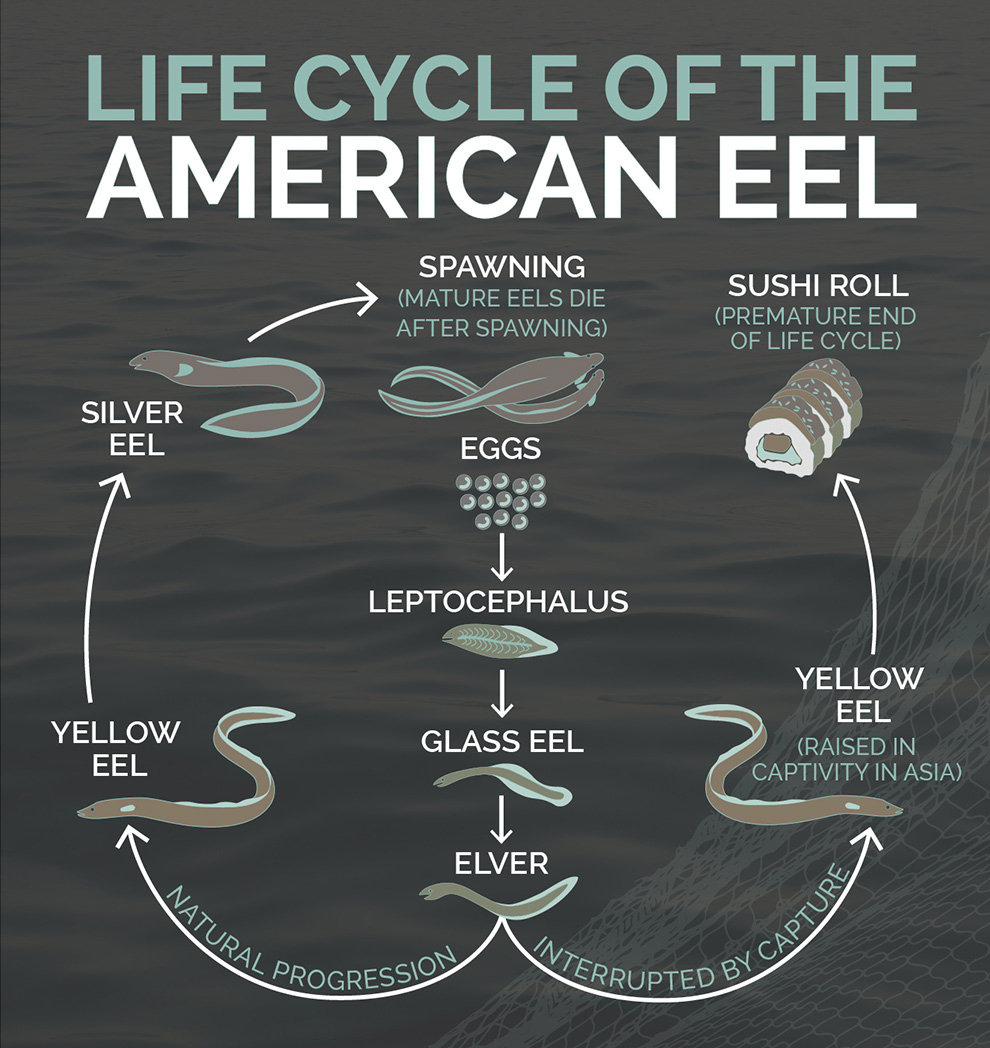

The elvers flew out of Logan or JFK international airports to China and Taiwan in clear plastic bags filled with oxygenated water to feed the fastest-growing animal-feeding operations on the planet: Asian aquaculture. The baby eels, two inches long with glassine bodies, nearly invisible sperm-shaped fauna with a thin black vertebrae and a pair of magnificent black eyes, swim inland on the final stretch of a five-month, several-thousand-mile-long quest to find a freshwater home.

Eel farmers need babies caught in the wild since no one's reliably bred the species in captivity. They are reared in ponds like seedlings: Plant a farm with elvers and, in six months, a pound of elvers might yield 1,200 pounds of meat that then might, at $10 a pound, fetch $120,000. Seventy percent of eels, unagi, was sold in Japan, according to one estimate by the newspaper The Yomiuri Shimbun. James Prosek's seminal book on the subject, Eels, reports that some 40% of eel eaten in a Manhattan sushi joint probably flew from Maine to Asia and back again. Scarcity drove the prices up and, stream-side, a pound of elvers sold for around $2,000. Rumor had it some fishermen were clearing nearly $100,000 a night.

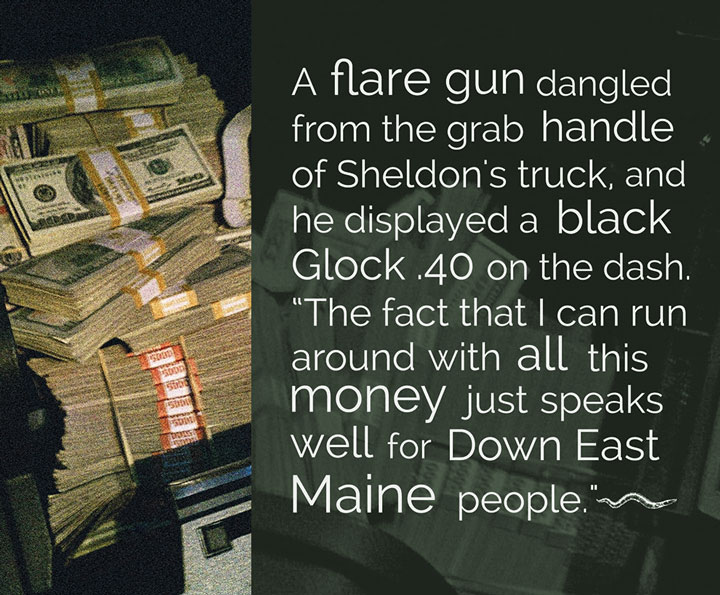

Recently the local paper, the Bangor Daily News, reported that MS-13, the El Salvadorian drug gang, was after dealers' cash. A pillhead had also followed Sheldon down to the river one night. "If I was sitting in New York City, selling roses or whatever, chances are I'd get robbed," he told me. "The fact that I can run around with all this money just speaks well for Down East Maine people. Certainly some bad apples. But to be able to operate like this, I don't know what it means, except what I just told you." Elver fishermen returned with wads of hundreds when Sheldon overpaid, which happened quite often, probably, I'd guess, on account of taking prescription medical marijuana. Nonetheless, he wasn't taking any chances. A flare gun dangled from the grab handle of his truck ("So I can shoot him in the guts," he said, pointing the thing out the driver's side window), and he displayed a black Glock .40 on the dash.

Everywhere the elver dealer went so did Larry Taylor, a stocky, 48-year-old guy in jeans and a sweatshirt. Taylor had a concealed .45, a 9 mm in his belt, and a 12-gauge pistol-grip pump. A friend told him Sheldon was looking for someone with a concealed carry permit, and Taylor, a contractor, was laid off, he said, "because of mud." (Mud season, in other words, makes outdoor work all but impossible.) All morning, the two dumped buckets of eels into a fine-mesh net. Before daybreak, a young woman in rubber boots and a big sweatshirt pulled up to the parking lot. Small talk.

"How's little Alyssa?"

"A little better."

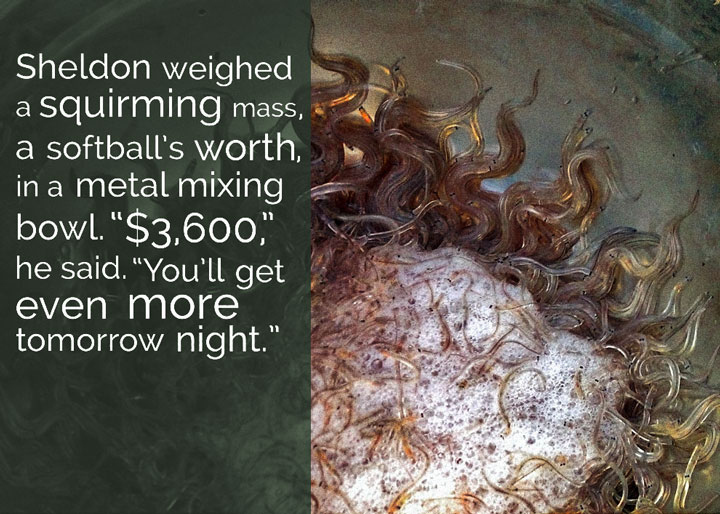

Sheldon weighed a squirming mass, a softball's worth of elvers, in a metal mixing bowl. "Thirty-six hundred dollars," he said. "You'll get even more tomorrow night."

"I will? That's good."

A while later, another fisherman rolled in with less than a fifth of a pound. Sheldon hopped behind the wheel of the Eel Wagon. "Nobody else caught nothing," he said, punching numbers on the oversize buttons of his calculator. "Six eighty-four," he said, and counted out $700. "Have breakfast on me."

Around daybreak, Taylor drove over to Dunkin' Donuts, and then the two went back to Jasper's Motel, where they continued dealing in the back lot.

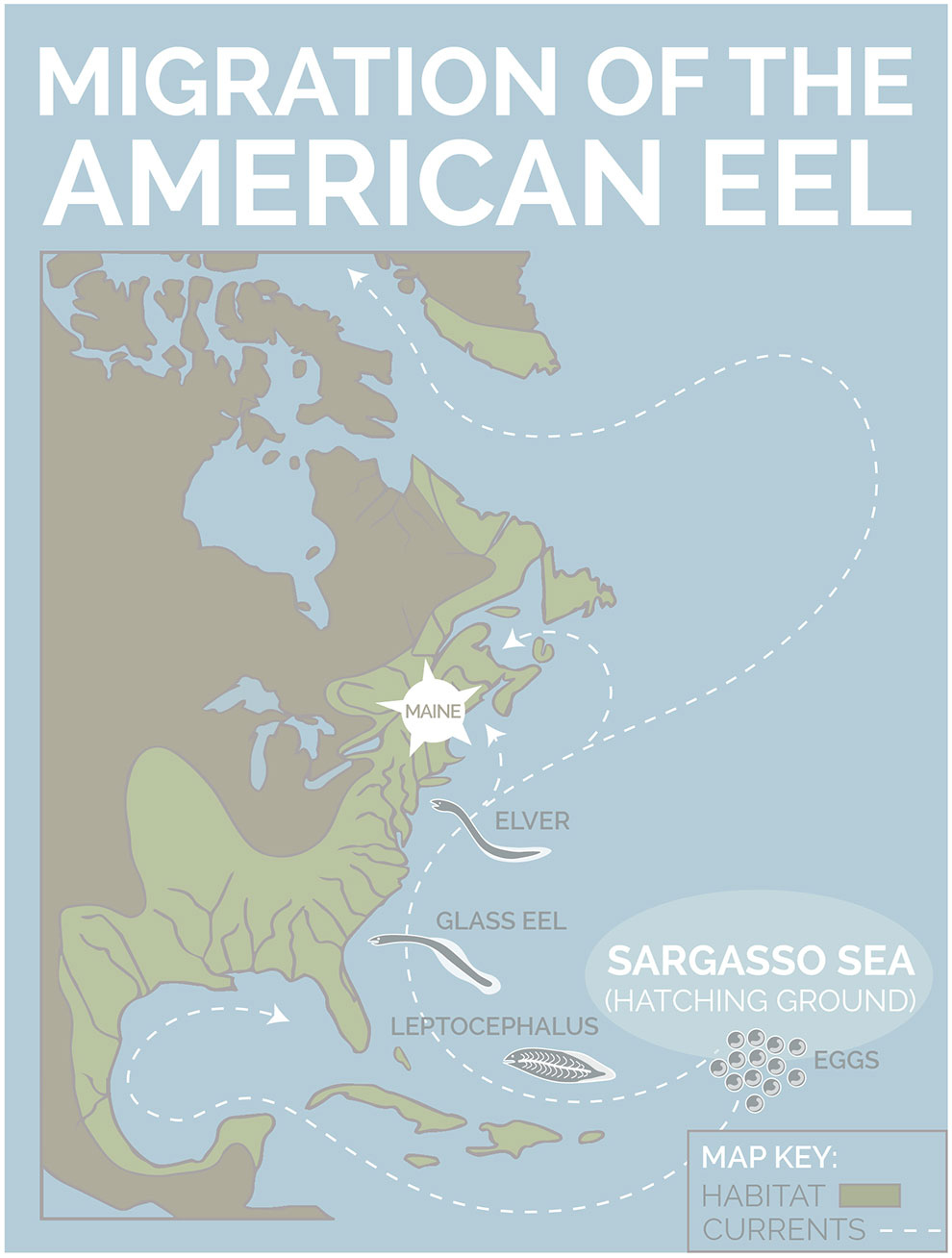

Over the next two springs, 1971 and 1972, Sheldon found transparent elvers — "glass eels," as he called them (he and many others use the terms interchangeably) — swimming up every stream he visited: the Kennebec, the Penobscot, the Pleasant, and the St. Croix. The transparent fish shimmied over waterfalls, rocks, fishways, and straight up the face of hydroelectric dams. His report, "Elvers in Maine: Techniques of Locating, Catching and Holding," describes the basic life cycle: In November, orphaned at birth in the mysterious depths of the Sargasso Sea at the heart of the Bermuda Triangle, eels begin their elusive migration as transparent ribbons "shaped like willow leaves." Known as leptocephali, literally "slim-headed creatures," they float up the East Coast on the North Atlantic Drift and — with no homing instinct — they're blown inland. They wriggle toward the smell of freshwater in Florida, up the East Coast all the way to Maine and Greenland, or to the coastal waters of Haiti and Venezuela if the currents carry the larvae southward. In freshwater, translucent glass eels develop into pigmented, serpentine elvers.

Eels live for up to 20 years, and the American species, Anguilla rostrata, once inhabited nearly every body of freshwater east of the Mississippi. Sheldon didn't say then — and no one can really say to this day — why eel migration is the reverse of most other fish and why at the end of their life the entire population heads back to their birthplace in the Sargasso Sea where they have one last orgiastic night before dying. "Wherever eels spawn," he wrote, "it seems likely that the entire North American population could be sustained by the spawning of adults from only a few of the freshwater population."

A mature female pumped out as many as 22 million larvae, and where brackish tidewater met freshwater, Sheldon began catching them in a homemade Sheldon's elver trap, a shoebox-sized cage cobbled together with wood and a window screen with a garden hose for a carrying handle. He sent one batch to Japan just to see if they made it alive. They made it, but Japanese buyers preferred the Japanese eel, Anguilla japonica. A pound of American eels were worth $30, so Sheldon went into the lobster business. By the late 1970s, a Washington Post headline read, "Japan Interested in Maine Trash Fish." ("For a while," the Post story said, an eel fisherman "was getting $300 per pound… But the bottom fell out after only a few months." One guy kept elvers in a wooden water tower in an attempt to stockpile but he too was left with nothing when the market crashed.) Former North Carolina Sen. Jesse Helms accused Japan of manipulating prices in 1978; a buyer in San Francisco told the Wall Street Journal that Americans simply didn't know how to handle their eels.

Sheldon began chasing the elver runs, traveling to Florida in January and fishing right up the East Coast. It was legal in all the coastal states. Elvers reached New Jersey in February, and when they hit Maine in March and April, he came home. In 1995, a shortage of Japanese eels sent prices from $55 a pound to $300, and anyone with a mesh net began staking out claims. Police reports began filtering in that year: Fishermen pushed each other into streams, fistfights broke out, and gas tanks, some said, were being filled with bleach. Property owners lobbied to keep the working-class trespassers off their waterfronts. Those selling adult eels for bait wanted to put a stop to catching the baby elvers. Sheldon argued the high natural mortality rate meant any elvers he caught might be eaten by predators anyway. By the late 1990s, Florida, Connecticut, and New Jersey banned elver fishing. One 1999 Bangor Daily News editorial said fishermen could not be blamed for an apparent decline in eel populations; these laws were motivated more by snobbery than biology.

In 1997, Watts petitioned the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to have the species listed as endangered. Nothing really happened. In 2011, Craig Manson, a former Bush administration official and the head of a nonprofit in California called the Council for Endangered Species Act Reliability, or CESAR, sued the feds. Some fishermen suspected Manson was part of a right-wing conspiracy to disrupt the Endangered Species Act. What better way to get the attention of East Coast politicians than by listing the eel as endangered and forcing federal agencies to remove some 25,000 dams to accommodate them, sabotaging the Act's reputation to force the issue of reform? When I put these allegations to Manson, he said, "My mother would be shocked to hear that." The legal petition he filed, if anything, appeared to exhibit a genuine concern for the species even if it was, as Watts said, some sort of "nine-dimensional chess." Either way, Watts said with all the cash being waved around, the overseas demand guaranteed a state-sanctioned extinction of some of the last eels left on earth. "We're giving our birthright to a bunch of people from Asia. 'Here, have 'em! Drive 'em to extinction!' In 20 years, the truck I bought with that eel money, the oilcan's going to break on a dirt road and I'm going to be divorced and that's it! There's your species! This is the economics of planned, deliberate extinction."

Scientists from the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources consider the European eel (Anguilla anguilla) endangered and met in July to discuss the imperiled status of the Japanese eel. Meanwhile, American eels went from $300 a pound to $3,000, creating a black market halfway around the world. If the nighttime standoffs and the poachers caught in New Hampshire and Rhode Island this year were any indication, the promise of striking it rich — with or without a state-sanctioned license — proved irresistible all along the Atlantic coast. In early February, three men were caught with 24,250 elvers in New Jersey. (One of them, Robert Royce, was once allegedly involved in a scheme to import 25 tons of marijuana from Haiti. He'd since changed his last name but not, it seemed, his ways.) Marine patrol officers caught another New Hampshire man in Maine with over 100,000 illegal elvers. Selling a pound of illegal elvers would probably cover the fine.

One morning, after Sheldon smoked his prescription meds and began writing out receipts, I asked if he ate at the sushi place across from his motel, which sold roasted unagi (freshwater) and anago (saltwater) for $5.50 and a signature roll with eel for $12.50. Eel tasted like spaghetti, as far as he knew, but the Asian chefs were after the texture. They filleted and grilled the oily flesh over an open flame, or steamed and smothered the meat in soy sauce. Every year, Japan celebrated Doyo Ushi No Hi, a traditional eel-eating day in late July when restaurants served unagi as a source of stamina during the sweltering summer heat.

"I had smoked eel one time," Sheldon said, "and I tasted it for two days." All of a sudden, he opened his door and rolled out of the Eel Wagon, leaving its door ajar, money locked under the armrest. Seconds later, he returned with a single elver, a translucent wriggling worm of a fish, its thread-like black spine visible through the skin. The elver tickled his palm. He tilted his head back, opened his mouth, and dropped it in. Eyes closed, Sheldon gripped the skin around his Adam's apple. Then, he swallowed and waited. "Right around here," he said, "he starts swimming back up."

"I don't have any for you. I'm selling to China."

"Well, we pay you the same."

"Nope."

"Well, we pay you more."

Sheldon then called his buyers — Chinese guys who wired him $600,000 on handshake deals — and said, "These guys want to pay me more for the eels. It's pretty hard to turn down a bigger offer."

"We'll match the price. Fuck the Koreans."

That, in so many words, Sheldon said, was the reason so many dealers and fishermen and poachers were running around. There was simply too much at stake.

Six hours into the day and not yet 9 a.m., his cell phone went off, a duck call: quack, quack, quack. "Go ahead," Sheldon said.

"Sorry to bother you. It's Solomon. You down by the river or up at the hotel?"

"At the hotel. Take your time."

A stream of water spilled into the parking lot at Jasper's Motel and a line of fishermen formed — lobstermen in hip waders, young guys in Adidas track pants, a woman in a neon Harley sweatshirt. All carried five-gallon buckets outfitted with battery-operated aquarium pumps. The pumps had names like Hush Bubbles and sold for $15 down at the pet store. Fishermen dumped buckets of water through a fine-mesh net. Sheldon weighed out the elvers and counted out hundred-dollar bills. Around 9 o'clock, a woman with brown hair who looked about 40 walked toward Room 27.

"I don't need toilet paper," Sheldon said, shouting. "I don't need towels." (The housekeeper took him seriously and delivered neither towels nor toilet paper to Room 27.)

One of the guys standing at the Eel Wagon said, "He don't bathe."

Sheldon lowered his voice. "I don't," he said. "I'm in the water every day."

When he returned from his nets on the Union River, everyone else stood back. Four pounds and later six pounds. (For those keeping score at home: That's one night, a bad night, mind you, and he'd have paid out nearly 20 grand for those elvers.) One fisherman said, "The man can fucking fish." Sheldon said it was simply a matter of knowing when to set out your nets.

Prior to the arrival of the elver-dealing kingpin and his armed assistant, the Drug Enforcement Administration raided Jasper's Hotel in an apparent drug bust. Another morning I visited, Jeff Camber, 55, a self-employed blueberry farmer in hip waders and a Budweiser hat, brought his catch in. Camber held court in the parking lot as if he were giving a stump speech. (I couldn't tell if it was for the benefit of the press — or, as the fishermen joked, maybe he was running for local office.) He despised the semi-vacant strip mall across High Street, where drug dealers reportedly sold pills, $50 or $60 a pop, wide open in the parking lot. As much as a third of the eel money, by some estimates, went to pharmaceuticals. Camber said he'd found his daughter's works stashed all over his house and, on top of all that, she overdosed at this very motel on Christmas Eve. (She survived.)

It almost seemed too bad to be true, like a fish story in reverse. The kernel of truth I heard was this: We're just trying to scrape by, me and the lifelong clammer who walked bowlegged, the recent divorcée who'd spent her life savings fighting an ex-husband's cancer, or the guy who tried to get locked up every winter just so he could eat three square meals a day for the first time. Eel money paid taxes; it paid for "decent vehicles," and it paid to fix up family homes. Five grand of one woman's eel money went toward cosmetic breast surgery. (The recipient, a 28-year-old recovered drug addict who didn't have a job, told me it wasn't dramatic, but had been a boost to her self-esteem.)

Later that morning, Dennis Tozier, a big guy with sweat-matted hair, emptied his bucket and, referring to a long-simmering feud with another fisherman, said, "Back when it was $30 a pound, nobody was fighting."Another fisherman showed up with a clipboard. A group of men listened as Sheldon read a handwritten statement on why global warming probably meant more elvers would be coming to Maine. There were only so many places to put a net in and you only have two months to fish. They kept the middle third of the river clear for the elvers to pass through and stopped fishing two nights a week. No one really expected the money to last even if the species survived. The semi-exclusive club had to protect against poachers and the hundreds of Native American fishermen and women that some seemed to consider poachers. Everyone was trying to cash in on the most lucrative thing Down East Maine had seen in years. Camber, who claimed some Native American blood, said he'd threatened to conk out a guy with a tribal permit dipping in front of his net. I was later asked, rhetorically, I suppose, "Have you ever seen a glass eel on a cave wall?" Racism or resource scarcity, it was a fine line.

One Sunday night in late March, Donnell Dana, in patched denim jeans and a camo Remington ball cap, walked along a silvery mat of grass with a dip net, a fine-mesh net mounted on the end of a long pole. He had seen the osprey and crow return to the Pennamaquan — its sandy banks still drained of color, the maple forest melting with snow — a sign that the elvers would come wriggling in on the nighttime tides.That night, 16 marine patrol officers parked green pickups near the bridge in Pembroke, a town straddling a remote tidal inlet about as far down and east as you can get in Maine. Their doors slammed shut and, with halogen flashlights drawn, officers unmoored three nets tied taught to the Pennamaquan's banks. All belonged to tribal fishermen.

The raid set off a cascade of phone calls and, within minutes, 50 Passamaquoddys — many from the Pleasant Point Reservation, a hurried 10-minute drive to the east — lined a narrow road, a winter's worth of dust swirling in their headlights. The state fisheries commissioner, Patrick Keliher, received intelligence from U.S. Customs and Border Protection that an additional 150 members of the tribe crossed from Canada into Calais, 40 minutes to the north. State police arrived for backup. (Because of amount of cash going around, the commissioner later told me, a lot of guns were being carried.) Frank Miliano, 6'3" and 200-some-odd pounds with tattoos lining both his forearms, rushed toward the state officials, according to Newell Lewey, a tribal leader with a runner's physique, glasses, and a graying ponytail, who held Miliano back by his shirt. Miliano was pissed, Lewey told me, saying, "No fucking way you're taking my fucking net."

Dana heard the commotion down below and kept dipping for elvers. He didn't want to argue about fishing. He wanted to do the fishing. Dana strayed no more than a mile from home; he didn't feel welcome further south where rival fishermen might cut his nets or steal his catch. Most nights, he drove home and combed sand fleas out of his catch with a pool skimmer and a credit card.

Down the road from Dana's house, a black Mercedes full of Asian traders pulled into Tim Sheehan's gravel lot, six hours from Logan Airport, looking for elvers. Sheehan, a boyish former biology teacher turned seafood dealer, said the elvers arrived at the end of winter when there was nothing, when everyone was dirt-poor, when the clam prices were down. The sardine canneries had closed, the cod were long gone, and urchins disappeared overnight. Elvers offered a $40 million opportunity in a county where the official poverty rate stood at 20%. He'd even offered to go 50/50 on nets and waders with tribal fishermen.

The threat of listing the entire species as endangered had, in effect, capped the number of Maine elver fishermen at 744. When four new licenses came up for grabs in Maine earlier this year, 5,200 residents applied for the lottery. Tribal leaders — asserting a historic and inherent right to fish — sold 575 licenses, which prompted commissioner Keliher's visit. Maine was no longer in compliance with a federal management plan, jeopardizing the entire elver season. After visiting his kids on Easter Sunday, Keliher drove to the frigid banks of the Pennamaquan to take a stand.

Dana, 57, born to a Passamaquoddy mother and a white father, has been fishing since the early 1980s. He fished for elvers with a state-recognized tribal license. When I asked about the tattoo on his wrist — AIM, for American Indian Movement — he said it was a mark of drinking too much on the reservation when he was 16. Once before, state officials threatened to take away his right to dig for clams and dive for urchins and, when that happened, in 1995, Dana said he'd go to jail before buying a license. Now he didn't want to get involved. He wasn't looking for trouble, and his son was out on probation. There were no jobs. A fishery might collapse overnight. He'd seen it happen before. If officials shut this one down, you could kiss the elvers good-bye. Chances are he'd never see opportunity like this again. (I never saw him again; the cell phone number he gave me has an automated greeting, "Your call has been forwarded to an automatic voice messaging system of" and someone, Dana presumably, says, "Captain Morgan.")

By the time I heard the story of the Easter Sunday raid from a dealer named Randy Bushey, a wiry guy with a cigarette-stained mustache and a gold lobster lapel pin, he said he'd tipped Keliher off after buying elvers from a tribal fisherman with a license numbered 566. That Sunday, Keliher stopped by his seafood dealership on the drive to Pembroke. According to Bushey, he said, "What are you doing, Bush?"

"Breaking out the Winchesters," Bushey told the commissioner. "You're going to need them."

Keliher claimed that these rumors about an armed standoff in the middle of the night between "nine wardens and 400 Indians" at best represented an exaggeration of a much smaller truth, like someone had caught the fish of a lifetime.

At the heart of all the conflict, though, the elvers did appear to be the fish of a lifetime — even if it were just enough eel money to put a roasted chicken on the table or a grilled unagi to quell the heat, whether it was the fate of a species or just some pills or a joyride in a small plane above the reservation.

When I met Newell Lewey, a tribal leader whose house overlooks the Pennamaquan, he told me the Passamaquoddys had fished and hunted long before previous gold rushes decimated cod or herring or urchins. The tribe would never cede its rights. The state's limit on elver licenses was a thinly veiled attempt to take what little opportunity there was left. "It's like throwing one bone to bunch of hungry wolves. Five hundred years of this," he said. "Divide and conquer. That's what they do best." Lewey told me twice, just to be sure. "It's like throwing one bone to bunch of hungry dogs."

Further north, where the St. Croix River divides St. Stephen, New Brunswick, from Calais, Maine, cars lined up on a bridge at the border. Underneath, a single elver net bobbed like an oversize white condom stretched by an icy, swift-moving current. Behind a brick Customs and Border Patrol building, Doug Wood and his dad John sat in a white van buying elvers; the sign on the side of their van said, Got Glass Eels? (The upside to working near Customs, the younger Wood told me, was the lot had 24-hour video surveillance. He still kept a handgun holstered under his jacket just in case.) Through a barbed-wire fence, down a rain-slicked trail, the river bobbed with 17 nets — all Passamaquoddy fishermen.

One evening, I met Fred Moore III on a street that dead ends at the river. Moore, 53, a ruddy-faced man missing lateral incisors on the left side of his mouth, coordinates the tribe's fisheries committee. We were accompanied by Mark Richter, 50, a former member of U.S. Airborne who acted as security. He had a sheathed hunting knife on his belt and, Moore told me, a concealed carry. The spring peepers had just emerged in the brooks, and we walked to Moore's camp, a blue pop-up tent with two nylon chairs and a pile of Dunkin' Donuts coffee boxes.

The wind picked up on the riverbank at twilight. High above the rushing river, an icy 38 degrees, a colony of turkey vultures circled. The black birds, with distinctive V's notched in the underside of their wings, moved in a slow counterclockwise flight. They arrived when the interstate was built, Moore said, and they were chasing an osprey. He descended into thought. "We can identify with that osprey. Got its rights from the same place we did. Vultures come by and attempt to drive it out. When newcomer government convinces the osprey to leave, we'll be right behind him." Moore laughed.

He'd been accused of being an instigator, telling tribal members they ought to fish. Bounties on Indian weren't popular these days, he told me, but the tribe seemed to be hated just because they existed. Moore said he personally went to meetings with state officials when he might otherwise be fishing because he didn't know who would do it. As I was about to leave, Moore said, "Why's a dog lick his own dick? Because he can." He laughed again. That night, he caught two wriggling elvers and set them both free.

Maybe these elvers were among those that survived, scaled the Grand Falls and Woodland dams, and lived out their lives. In 20 years, perhaps they would evade turbines and fishermen and bluefin tuna and porbeagle sharks and make the long migration back to the Sargasso Sea. The life cycle of the American eel ran counter to almost every other known fish. Some suspected the story of the eels ran counter to endangered species cliché "You don't know what you've got till it's gone." In truth, no one ever knew what they had.

"Did something right tonight," Tilghman said. "I guess."

"Sure. Been waiting for that." Sheldon weighed out a bowl full of elvers. "Two point three four," he said, and counted out $100 bills. As I recall, the one-armed fisherman pocketed $4,200 that morning.