In the 1920s and 1930s, the port city of Stockton, California, was home to so many Filipinos that a section of town was dubbed “Little Manila.” Filipino American writer Carlos Bulosan wrote of walking down Stockton’s El Dorado Street around that time in his semiautobiographical novel America Is in the Heart, published in 1943. He saw Filipinos dressed in sharp suits while standing in front of pool halls and gambling houses. He wrote, “There must have been hundreds in the street somewhere, waiting for the night.”

Stockton is a different town now. In 2012, it was the largest city at the time to declare bankruptcy. It exited bankruptcy in 2015, and now it’s working on new strategies to improve its economy. Filipino Americans are the largest Asian American group in the city, but the community has changed since Bulosan first arrived. Last year, this resilient group experienced a sobering reminder of Little Manila’s legacy.

The Little Manila Center is a cultural and educational meeting space in downtown Stockton for the area’s Filipino American community. Last October, during Filipino American History Month, the center was vandalized. There were ripped banners and a set of misspelled, nearly illegible words like “whittie,” “brainwashed,” and “bigots” scrawled on a window.

Among the first to witness the damage was Celin Corpuz, a high school student and member of the center. She posted photos of the vandalism on Twitter. “I wanted to spread awareness that this happened in our city of Stockton, that hate crimes are real,” Corpuz told BuzzFeed Philippines. Upon deeper inspection, she tweeted, the words on the window could be read as “white property, you're a brainwashed bigot.”

Stockton Mayor Michael Tubbs responded to Corpuz’s tweet, calling the act “unacceptable.” In a statement to BuzzFeed Philippines, Tubbs said, “The impact of increasing racial hostilities at the national level has trickled down to communities like Stockton.” Tubbs added that, “although we will never know the true intent of the perpetrator until this person is caught, we remain very concerned about the circumstances surrounding this criminal act, against our Little Manila Center, during Filipino American History month, last year.”

The Stockton Police Department took a report and conducted an investigation, according to police spokesperson Joseph Silva. A white woman who appeared to be homeless was a suspect in the case, but no perpetrator was identified and the case was eventually closed. The incident was ruled a vandalism and not classified as a hate crime.

“I feel like it was an attack on our community,” said Brian Batugo, arts program director for the Little Manila Center. On the day of the incident, Batugo showed the destruction of the center’s exterior in a Facebook Live video, calling it a “suspected hate crime.” Commenters posted messages of shock, sadness, and anger, though Batugo said there was some controversy about the gravity of the situation.

“I know some people were rallying under, like, ‘Little Manila Strong,’ and usually that hashtag is reserved for, you know, there was this horrible incident and there’s death,” Batugo said. He added that what happened is subjective and “depends on how you look at it.” But to deface a community center with racially charged speech, at a time meant to celebrate their community’s history, felt like an assault, especially for young members like Corpuz. The act served as a reminder of the struggles Filipino Americans have faced for acceptance and respect in Stockton specifically, and in the US in general.

Filipino American culture has been in the news in recent years, most notably with the rise of Filipino food’s popularity. But with every piece written about the nuances of Filipino cuisine, and in turn, Filipino culture, there are many more that claim to discover a people who have been here for decades. Filipino food, in all its sour and salty glory, may finally be having its long overdue moment, while less savory elements of our culture and history are left behind. Issues that don’t fit into the pretty picture of what’s currently on trend in Filipino America are swept under the rug — like an act of racism that took place in a small Stockton community. Filipinos have been in the US for over a hundred years and have had a colonial history with the US for even longer. But for some reason, all people can think about when it comes to Filipinos are lumpia and chicken adobo.

The earliest recorded arrival of Filipinos to the United States was in 1587, in Morro Bay, California. But the first significant wave of Filipino immigration took place at the turn of the 20th century. When the Philippines was colonized by the United States in 1898, Filipinos became US nationals and had the legal right to work in the US. In the book Little Manila Is in the Heart, San Francisco State University professor and Little Manila Foundation cofounder Dawn Bohulano Mabalon wrote that young Filipino men left Philippine provinces to work as contract laborers — sakadas — on the sugar plantations of Hawaii. From there, many moved on to fill a growing need for cheap farm labor on the US mainland.

Located in the San Joaquin Valley, Stockton became a popular destination for newly landed Filipinos in the 1920s and 1930s. Little Manila included the downtown streets of Lafayette and El Dorado, which were lined with Filipino businesses like barber shops, shoe shiners, pool halls, and restaurants. The US was the dream for these mostly young, single, and male Filipino immigrants, often called the generation of manongs, or older brothers and uncles. Stockton was a central place for them to reconnect with friends from their respective provinces back home or to spend their hard-earned money in bars, gambling dens, and brothels.

But these manongs paid a steep price for the American dream. They sold all of their possessions for a one-way ticket to the US, imagining a country full of opportunity. Instead, they found stoop labor jobs in poor working conditions. Mabalon wrote that “work in the fields, and horrific farm labor conditions, low wages, and industrialized agriculture taught Filipina/o immigrants their place: at the bottom of the racial hierarchy in Stockton.”

Filipinos faced racial discrimination and violence. According to Mabalon, the first recorded violent anti-Filipino incident in the US took place in Stockton on New Year’s Eve in 1926. “Eight whites and Filipinos were stabbed and beaten,” Mabalon writes, “when white men entered hotels and pool halls, looking for Filipinos to attack.” The Stockton Daily Evening Record, which Mabalon says was anti-Filipino, reported that “Filipinos ran amuck, attacking whites,” instead of blaming the white culprits. In late January 1930, riots broke out in nearby Watsonville, in which whites “shot at and beat Filipinos indiscriminately.” Hundreds of armed white men hunted down Filipino farmworkers for five days, resulting in the death of a 22-year-old named Fermin Tobera.

On Jan. 29, 1930, a white mob bombed Stockton’s Filipino Federation Building. The Healdsburg Tribune reported that “whites in an automobile hurled a bomb into the building, blowing the façade clear across the street and throwing occupants of the club from their beds.” No one was killed, but the message was clear. Things were so hostile for Filipinos during this time that Bulosan’s America Is in the Heart referred to it as the “year of the great hatred: the lives of Filipinos were cheaper than those of dogs.”

Anti-Filipino incidents stemmed from the aggression of white nativists and Dust Bowl migrants who felt they were losing job opportunities to Filipinos. Filipinos were known to growers and labor organizers for being militant, borne of a need to defend themselves from mobs and to fight for their labor rights. Though they came from various provinces in the Philippines — many were Ilocanos, Visayans, and Tagalogs — they banded together across regional and linguistic divides to advocate for higher wages and better working conditions. They picketed and organized strikes during the peak of the harvest season, hurting growers financially.

When faced with armed confrontations, some Filipinos retaliated. In Little Manila Is in the Heart, Rene Latosa recounts how his father, Johnny, a labor contractor, participated in shootouts with white vigilantes: “They would drive by, and boom boom boom, and then they’d keep going. This is how they lived during that Depression. They fought for their jobs.”

Labor unrest led to clashes, not only with the ruling white classes, but with other minority groups, too. Growers hired poor whites, Mexicans, Indians, Japanese, Chinese, and Filipinos, pitting them against one another by means of segregated housing, unmatched wages, and unequal treatment. When Japanese farmworkers became growers, they were accused by Filipinos of perpetuating pay gaps among ethnic groups. Filipinos held strikes on Japanese farms and boycotted Japanese-owned businesses in Stockton. They also broke strikes of Mexican workers and other Filipino crews, which sometimes resulted in violence.

Because of these harsh living conditions, few Filipina women immigrated to the United States. Filipino men socialized with white women, escalating racial tensions. In California, Filipinos could not marry white women or even own property. Signs that read “positively no Filipinos allowed” were displayed openly on hotels and other businesses around Stockton. Filipinos, along with other people of color, couldn’t cross Main Street into the richer, white sections of the city.

Little Manila was largely destroyed in the 1960s and 1970s due to misguided city policies, according to Little Manila Foundation cofounder and executive director Dillon Delvo. In 1999, as part of widespread sprawl development, city officials destroyed one of the last remaining blocks of Little Manila to build a McDonald’s and a gas station. Today, just three buildings from old Little Manila remain between a freeway and a crumbling sidewalk. The area is bleak and, in certain parts, deals for drugs and sex are conducted in broad daylight, Delvo told BuzzFeed Philippines. If it weren’t for some banners and signs that read “Little Manila Historic Site,” the area’s deep Filipino American history would likely be forgotten.

The Little Manila Center is about 15 minutes away from old Little Manila. When it was vandalized, Delvo wasn’t surprised. In fact, he was expecting it to happen and was relieved it happened the way it did. “No one was hurt. No one was getting deported,” said Delvo. “End of the day, it’s just some banners that can be easily replaced.” Months after the incident, the banners still haven’t been changed and graffiti is still on the window. Delvo said they will change things eventually, but he wants people to see what happened.

“I think what’s more upsetting to me is how some folks in the Filipino community have sided with Trump and those types of politics,” Delvo said. Following the 2016 election, a survey showed Filipino Americans were the highest supporters of Donald Trump among Asian Americans. Delvo said, “I actually like the fact that this has happened because I think it’s important for us to have reminders that the Filipino community is not exempt from hate.”

Delvo believes it’s important to acknowledge these moments especially in the context of Filipino American history, much of which has been forgotten. The Delano Grape Strike, led by Filipino American farmworker and labor leader Larry Itliong, is often overshadowed by the work of Mexican American labor activist Cesar Chavez. While Chavez and the United Farm Workers became the face of the Delano Grape Strike in the 1960s, Filipino farmworkers were the first to walk off the fields; it was Itliong who appealed to Chavez and his fellow Mexican laborers to join the strike.

This neglected history is also partly due to the nature of assimilation. When Filipinos faced dangerous acts of racial violence, they were often told to keep quiet by their own people. Mabalon wrote that, after the bombing of the Filipino Federation Building in February 1930, an editor of a local Filipino American paper said, “We must live here in such a manner to reflect the best that there is in the Filipino people. We must give them the right impressions.”

In America Is in the Heart, Carlos Bulosan wrote about the wonders of walking down Stockton’s El Dorado Street in old Little Manila. He found so many Filipinos that he hoped to “see a familiar one.” The asparagus season had ended and most of the Filipino farmworkers in town “had no other place to go.” But after witnessing violent acts of racism, Bulosan found himself questioning this new land and country. He wrote that the streets were not free to Filipinos, that they would be stopped each time they drove a car, that they were suspect when seen with a white woman. He concluded that “in many ways it was a crime to be a Filipino.”

After the incident at the Little Manila Center, things have gone relatively back to normal, with a slight difference: People outside the community started to learn about the center and even donated to help with repair costs. They raised about $3,000 from mostly Filipino American supporters. A bulk of the aid came from Filipino American college student groups. “The silver lining behind this is that people started paying attention,” said Batugo. “It’s unfortunate that it happened, but people started thinking, ‘Oh, there’s a center downtown that’s dedicated to Filipino American history and art?’”

The Little Manila Center opened in 2014, but the Little Manila Foundation, cofounded by Delvo and Mabalon, has been fighting for their community since 2000. Delvo says one of their main goals is to dig up the forgotten history of Filipinos. He believes that remembering and learning from their history is a way to empower their marginalized community.

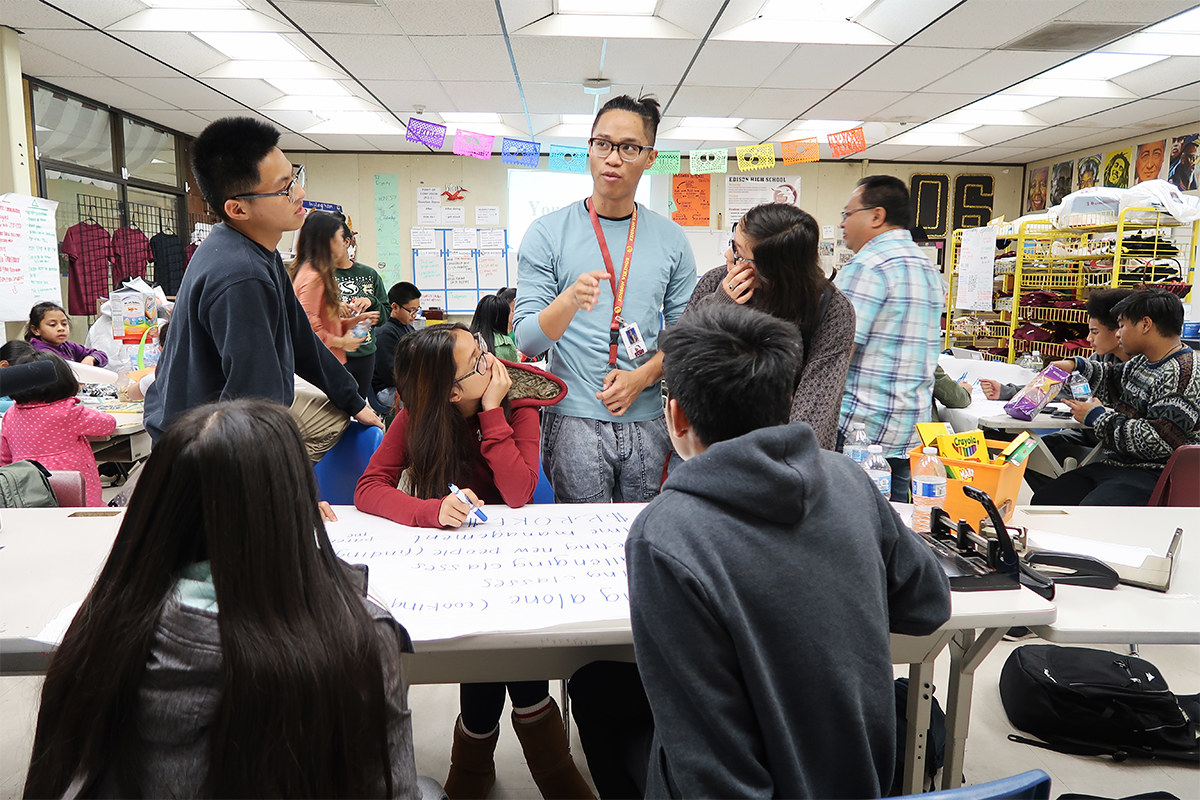

The center is like a museum aimed at preserving their fragile history. Relics from Little Manila’s heyday are displayed, among them black and white photographic prints and old wooden trunks filled with possessions of that early generation of manongs. Delvo said he teaches lessons about Stockton’s Filipino history to his students: “We’re trying to empower younger generations with this knowledge and connect them directly to it.

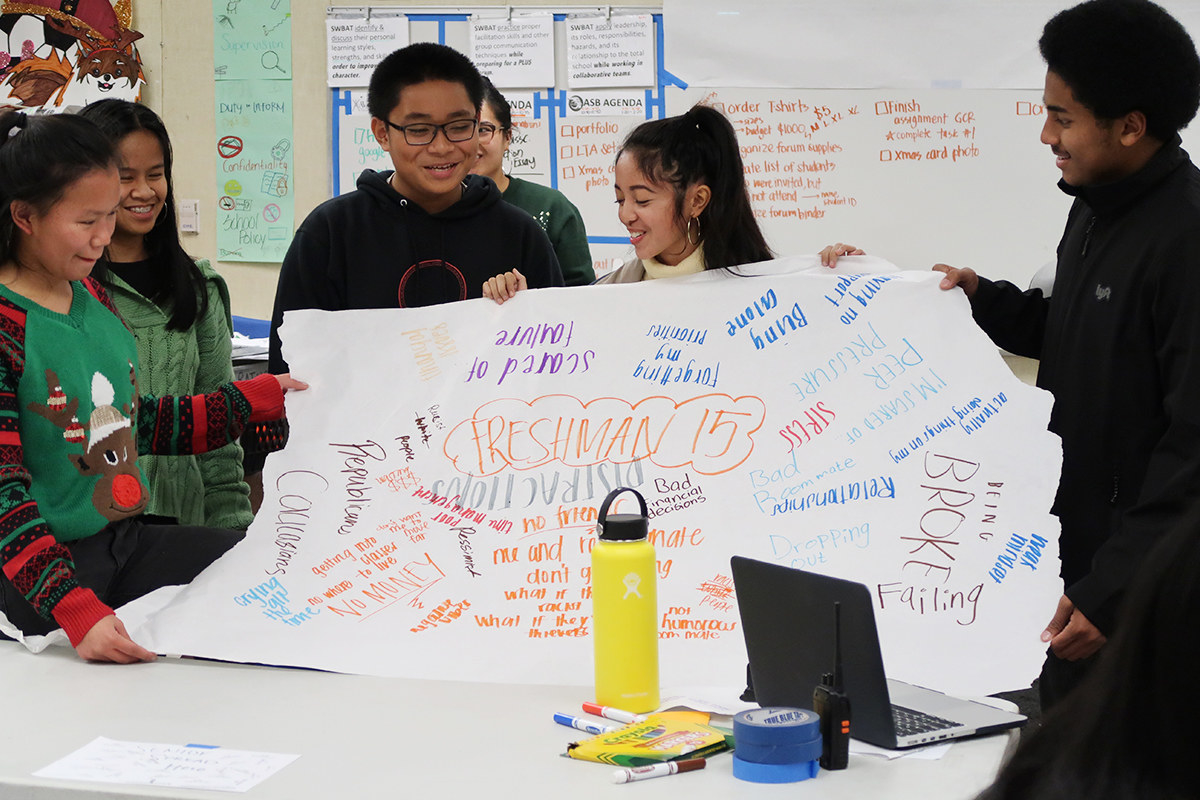

The center offers a traditional dance program and an after-school program where students come to learn about subjects like Filipino history and ethnic studies. They’re not graded for any of this work, but they show up every week to eat snacks and talk culture. “I really like learning about things that are not really taught in my own classroom, and I like the environment here because the teachers are amazing,” said Corpuz, a member of the Little Manila Center’s dance troupe and a participant in the after-school program.

To this day, Corpuz feels the vandalism that took place at the center was a hate crime. She and her friends move forward by being active members here, continuing their work in learning and promoting their community’s storied history and culture. “We embrace the fact that we got vandalized as a symbol of resistance,” she said.

Decades after Carlos Bulosan first wrote about his traumatic immigrant experience in the early 20th century, history has repeated itself in the 21st. An act of vandalism at a community center seems trivial compared to larger acts of racial violence, but it’s a reminder of what happened to Filipinos in the past and injustices faced by immigrants and people of color today. Indeed, Filipinos are not exempt from hate. If this had happened to another larger, more powerful group, would people have moved on just as easily?

While some aspects of Filipino culture may be more visible in mainstream American culture, there’s always room for more. Whether it’s by reading a book, or paying a visit, there are many ways to prevent the legacy of Carlos Bulosan, the manongs, and the Filipino Americans of Stockton’s Little Manila from being forgotten.