In the summer of 2013, billionaire Elon Musk posted a 58-page “alpha paper” introducing a futuristic “fifth mode of transportation” beyond planes, train, cars, or boats, which he called Hyperloop. The system would whisk passengers from Los Angeles to San Francisco in 35 minutes using magnetically levitating pods that traveled at high subsonic velocity in a steel tube. It was the engineering equivalent of rough draft, but the CEO of SpaceX and Tesla was too busy to build it himself. The whole point of publishing the document, he explained, was to open source Hyperloop, solicit suggestions, and “correct any mistakes.”

Legends do not typically start with a smart dude giving away a half-cooked idea for free on his company blog. Now, however, much like Musk’s other gambits, Hyperloop seems to be hovering (sorta) close to (the outskirts of) the realm of possibility.

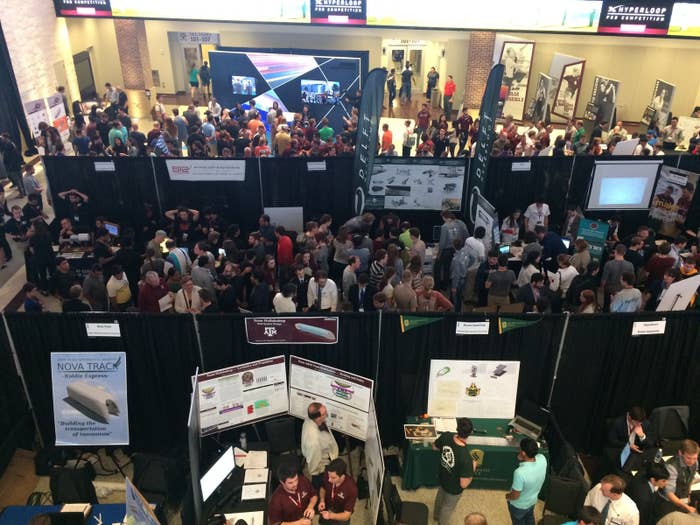

Late last month, it got even realer, as U.S. Secretary of Transportation Anthony Foxx gave the concept his blessing during the SpaceX Hyperloop Pod Competition, a two-day event hosted at Texas A&M University during the last weekend in January. A pod contest probably conjures images of Jetsons-esque vessels slapped together using space age polymers and Scotch tape. In practice, it was more like a highbrow science fair that doubled as a recruiting event for all things Elon. (When you’ve made yourself synonymous with colonizing Mars, you only need one name.)

The competition was organized by SpaceX and geared toward university students and independent engineers. The assignment was to submit detailed technical proposals for a pod that could withstand the 700 mile per hour trip. The weekend’s lucky winners were invited to build and race their designs this summer on a one-mile test track being built at SpaceX’s headquarters in Hawthorne, California. More than 120 teams participated, comprised mostly of undergraduate and graduate students in their late teens and early twenties from more than 100 universities around the world. A couple of high schools competed, as did a team assembled on Reddit that live-streamed their journey on Periscope, Twitter’s real-time video app.

The first thing contestants saw outside the stadium was a red canopy with the Tesla logo next to a Model X, the company’s newest electric vehicle. Teams who wanted to advance had to break down the cost of a pod and raise the funds to build it from sponsors or their school. Hence most seemed to come in well-under the Model X’s $80,000 retail price.

Achievement Unlocked: -Chill in a Tesla #breakapod

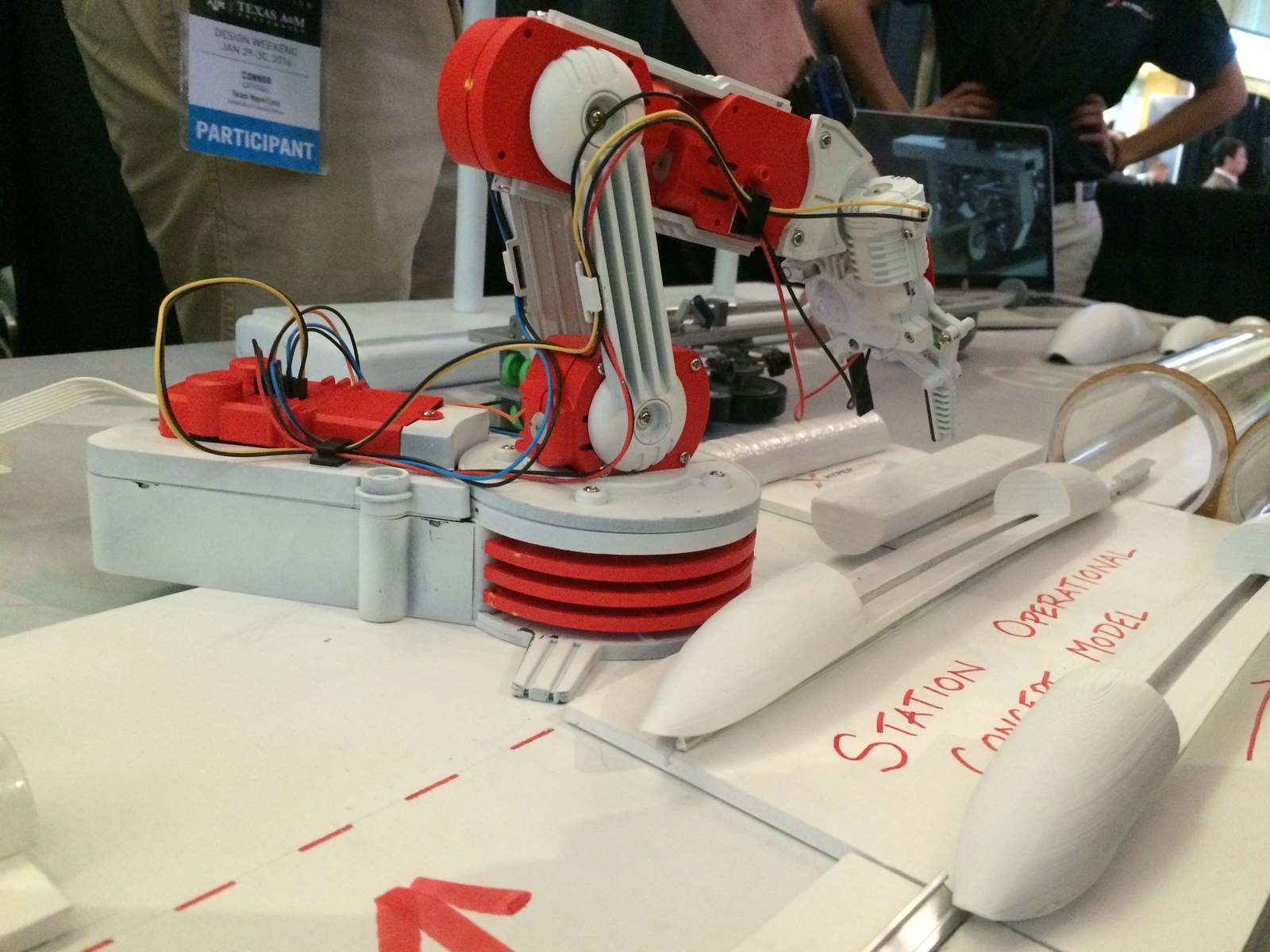

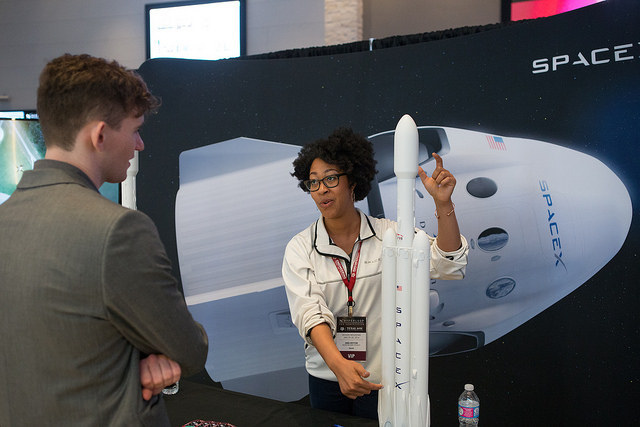

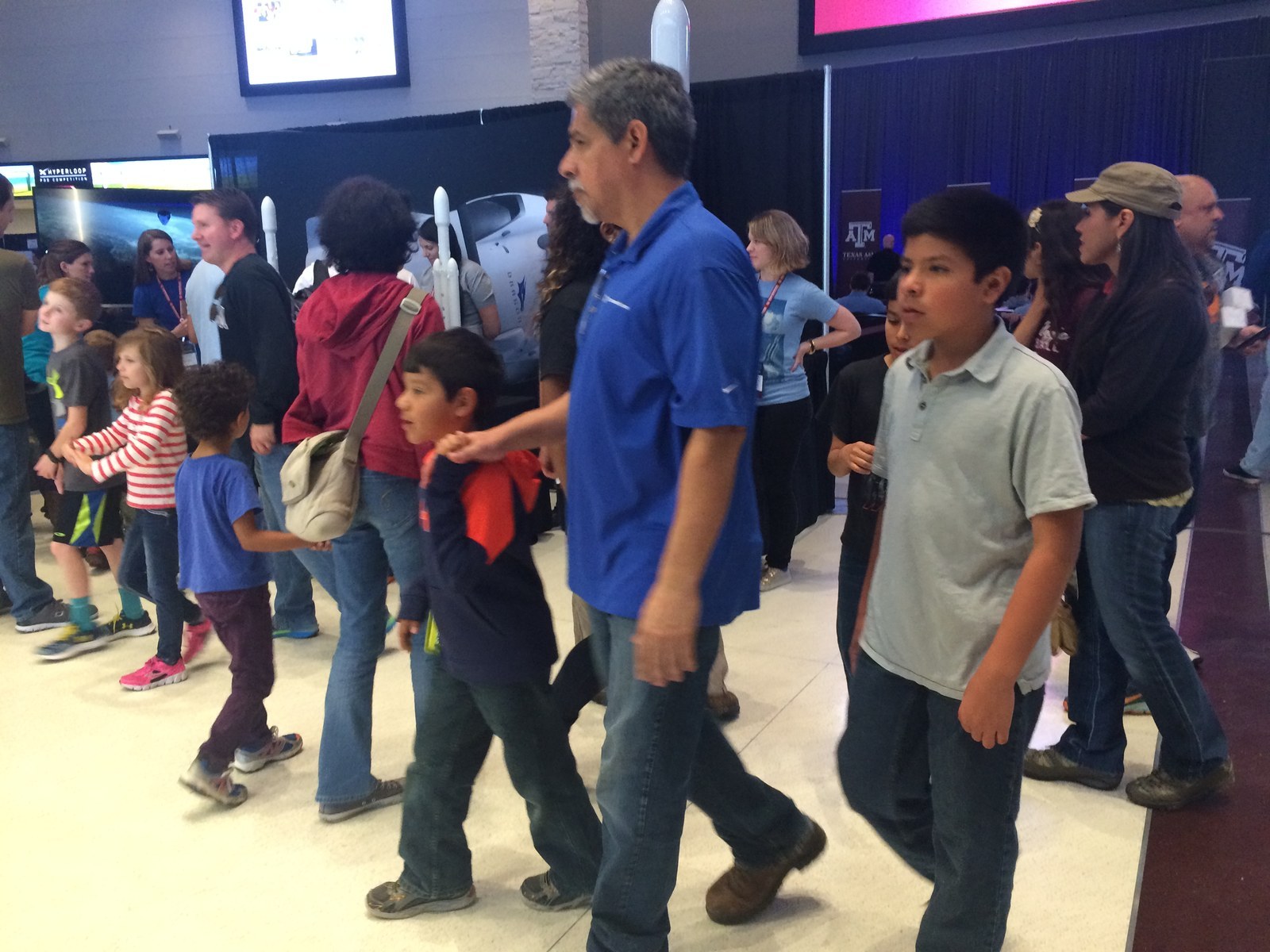

The science fair vibe came courtesy of rows of booths with as many poster boards as computer visualizations. Presentations covered topics like propulsion, aerodynamics, and braking. Tables featured props that ranged from Lego-like cranes (for loading pods onto the track) to 3-D printed pods to demonstrate magnetic levitation. The teams set up in the Hall of Champions, a 100-yard football-shaped atrium that ordinarily functioned as a “virtual museum” (i.e., a big room with lots of screens) celebrating the school’s athletic prowess. At the SpaceX table, located smack dab at the entrance, employees milled about in “Occupy Mars” hoodies and tees.

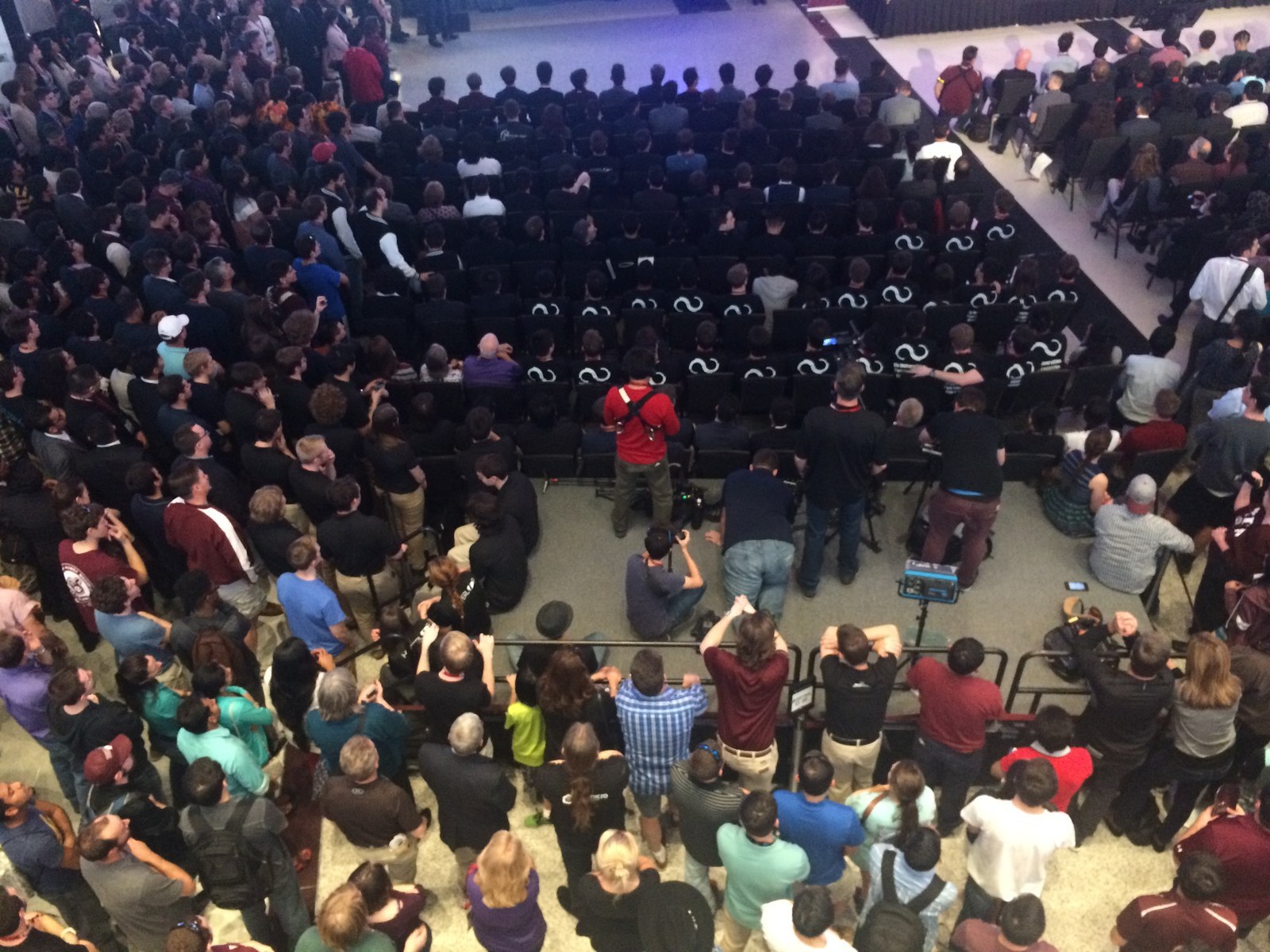

It was a tight squeeze for Foxx’s security detail, but he and the attendant camera crews toured the floor talking to the kids before taking the stage Friday evening. In front of a crowd of 1,000 engineering students, Foxx called Hyperloop the kind of breakthrough project that our ailing infrastructure system desperately needs, if not for the tubes, then at least for the tubespo. According to a Department of Transportation study, by 2045 there will be 70 million more Americans and a 45% increase in freight demand, so the federal government should consider backing big ideas that make young people want to fix our D+ transit system, he argued. “When Kennedy announced that we were going to the moon, that pushed American innovation a long way and I think you have the potential for a similar moonshot, if you will, here,” Foxx said.

Foxx wasn’t the only adult onstage that weekend who ascribed historical significance to the event. Dr. Gregory Chamitoff, a former NASA astronaut, compared it to watching the Apollo 11 landing. Professors told students that they could say they were here when it all began.

Can't @Hyperloop shout-out to everyone but did appreciate @teamhyperlift! https://t.co/SDGjyMK644

Turning a concept that looked, at first, like a nootropics fever dream into a Kennedyesque rallying cry to get the world’s best and brightest to care about congested roads is quite a coup. It’s also a trick that Musk has tried before. He revived '90s-era interest in electric cars (in the name of clean energy). He hit refresh on our 1950s fantasy of outer space (in the name of saving the human race). Rebooting American dreams left for dead seems to be his sweet spot. And Foxx’s imprimatur made it sound like Musk might be able pull it off again, this time with a sexless task-like infrastructure.

Whether you believe Musk’s messianic ambitions or call it personal branding for billionaires, there’s an incredible efficiency to his methods. He managed to associate SpaceX with Mars when the company was still struggling just to make cheaper commercial rockets. As the weekend progressed, it became clear that Musk doesn’t need to figure out a viable design for Hyperloop or watch a single pod bloom to reap the benefits.

All around him, motivated engineers were swapping ideas and dropping their resume at the SpaceX booth. No matter what, Elon wins.

For many contestants, Hyperloop weekend represented a modern alternative to Formula SAE, a popular international competition where students develop race cars for a fictional manufacturing company. Formula SAE has traditionally been “a great feeder system” for Musk, said Brogan BamBrogan, an early SpaceX engineer who launched his own commercial Hyperloop company. He said the track at SpaceX HQ was set up “with the specific intention of building a student interest competition around it.” For the students who made it College Park, the choice was a no-brainer.

“It’s a pretty easy sell: ‘Hey, who wants to make something levitate and propel itself down a giant tube?” Paul Orozco, a 23-year-old student from Florida, told BuzzFeed News. If that didn’t work, he said, “you could go on about how you’re creating a fifth mode of transportation in a totally different way...”

There were 80 judges for the event, including engineers from SpaceX and Tesla as well as faculty members from different universities, in order to vet the technically rigorous proposals. Orozco was joined by his alumni adviser Capt. Curt Taras, an Air Force veteran and civil engineer. Orozco said he was “pretty giddy” after two judges came by his booth. “He was jumping up and down when Tesla asked for his resume,” Taras confirmed.

In the middle of America and far from the app incubator that is the Bay Area, Hyperloop’s potential seemed less foolhardy and more feasible. After all, these kids probably have a better sense of whether this is doable than your average venture capitalist. They were wide-eyed, but practical, eager to explain impossibilities from Musk’s white paper and fixes they found after months of sleepless nights.

The scale of Hyperloop was a contrast to the modesty of the surrounding city with its one-story strip malls and clusters of housing developments in different shades of beige. All three UberX drivers I hailed knew about the competition. Even the fact one could summon an UberX in College Station in eight minutes or less seemed like a sign that the future was coming — and that it would be owned by technocrats.

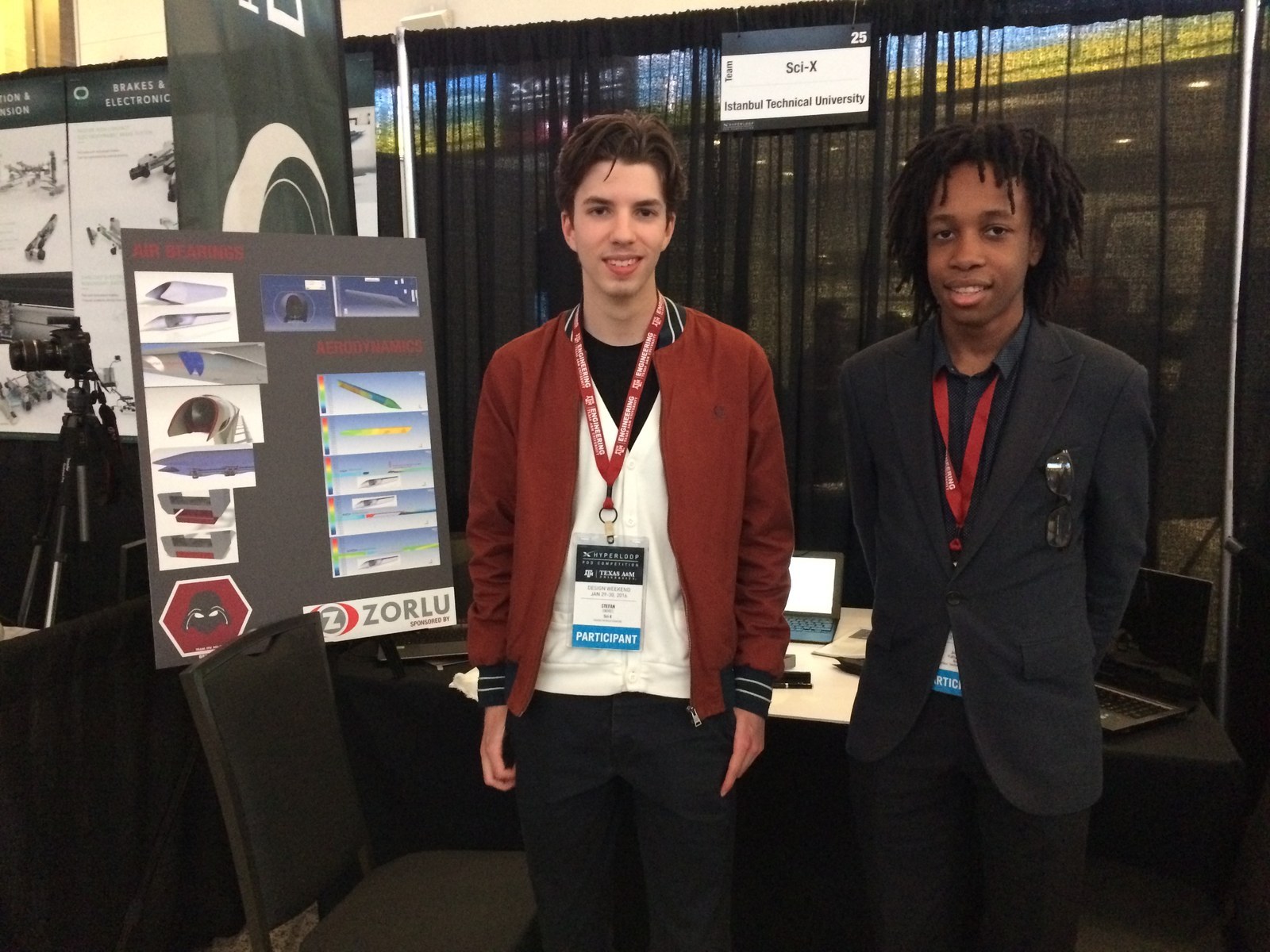

Some of the college teams had names like GatorLoop team from the University of Florida or the RIT Pod Squad from the Rochester Institute of Technology, but others included students from a cross section of schools, who spent months communicating from afar.

Jordan Kabyemela, a 16-year-old high school student from England, was on the Istanbul Technical University’s team, which also had members from Mexico and South Africa. Kabyemela, self-assured and dry, explained that the team communicates “through this website called Slack.” The group Slack is divided into channels on aerodynamics, analysis, and renders. There was also a general one about movies, where tastes diverged from “people who like Dark Knight Rises to Bratz: The movie.”

Joseph Stanek’s team was made up of students from three community colleges in suburban Illinois. “We didn’t expect it to be this awesome,” said Stanek, who is studying automotive engineering. “It’s just so surreal being down here and competing against MIT and big state universities.”

When I asked Stanek whether he follows Musk's exploits, he pointed me to the silver Tesla pin on the lapel of his sports coat from his part-time job as Tesla product specialist, the company’s term for salespeople, at its retail store in the Oakbrook Mall.

From almost any vantage point in the Hall of Champions, one could spot members from Open Loop, a 100 or so person team, half of whom were in attendance, all sporting T-shirts with the group’s swirly honeycomb logo. In fact, most of team wore matching gear. Hawaiian shirts for the Panther Pod team from Florida Tech; whereas the team to beat, Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands, wore stiff toothpaste-colored button-downs with the logos of their many sponsors printed on the back. Delft made their very professionalized presence known with huge fin-shaped signage that gave their booth twice the height.

Nova’s booth, in contrast, was in the same hallway as the concession stand, through a set of double doors and about as far as one could get from the stage. Twenty-two-year-old Cairo University student Samar Abdelfattah was the only representative of her team who could make it because her three teammates couldn’t get visas in time. Abdelfattah, whose headscarf matched her pink sneakers, said she learned about the competition from SpaceX, “mainly because we keep checking the website.”

Both Nova and the Reddit team, called rLoop, won awards that weekend. An rLooper named Eric Matzner was easy to spot because of the smartphone harness over his shoulder, which looked like an exoskeleton and made satisfying crunching sounds when he adjusted it. Matzner, the one live-streaming on Periscope, asked one of the reporters to type quieter during the opening ceremony.

A representative for SpaceX told BuzzFeed News that the competition did not track gender, but that roughly 10 to 15 percent of the team captains were women.

Hundreds of student proposals, even wickedly innovative ones, does not a “fifth mode of transport” make, but the weight of private funding and big brands buttressed the sense of optimism. There was a Lockheed Martin booth with an F-22 Raptor simulator (no real relation) and a whiz-bang set up from Arx Pax which makes the magnetic field architecture used by some of the teams, and used it to build the Hendo Hoverboard, which actually hovers. In fact, the most evocative rendering of Hyperloop came fromAECOM, the $4 billion corporation building SpaceX’s test track. Visitors who dropped by their booth could watch it through VR headsets.

Hours before the judging hall was opened to “the public,” which turned out to mean kids — actual kids, intensely curious ones — and their parents, who braved whatever space was left in the hall and in some cases traveled from Dallas or Austin for a glimpse. Near the Arx Pax area, one dad was trying to explain coefficient friction to his tweens. The 2 p.m. demo for hoverboard was crowded with children. “We put a baby on it before,” one of the demonstrators told a girl in the front row as they waited to get things started. “Whoa I’m 6! I’m 6!” she said, possibly to imply she’d be a much better passenger.

The best indicator of the burgeoning economy around Musk’s alpha paper is Hyperloop Technologies, one of two companies trying to commercialize the idea and arguably the farthest along. It was co-founded by Musk’s friend, early Uber investor and Obama bundler Shervin Pishevar, and Musk’s former employer, BamBrogan. Musk has said he will wait and see before backing any one company, which leads to a lot of people wanting to make “super clear” declarations about Musk’s lack of involvement that ending up coming out sort of hazy.

But in an interview with the co-founders and their new CEO, Cisco veteran Rob Lloyd, two themes came up that also put the concept (if not their implementation of it) closer to reality.

Lloyd repeatedly mentioned Hyperloop as a method of transporting cargo. While armchair industrialists worry about whether Hyperloop passengers will be able to pee, behind the scenes, well-funded folks are working on something your senator might want to stamp through. According to Lloyd, “U.S. regulators would love to see us solve freight and cargo problems” and would “be comfortable if that was the first commercial use cases” — pitched to, say, the same lawmakers who are looking into driverless cars. Once the cargo scenario is proven out, it would bring the company “just a step closer” to using Hyperloop for passengers.

Just like SpaceX was associated with colonizing Mars while its rockets were only traveling as far as the International Space Station, perhaps Hyperloop could symbolize exponential leaps in infrastructure, while the bulk of profits came from hauling cargo.

Hyperloop Technologies has already secured investment from China, Europe, and Russia and interest from regions contemplating high-speed rail projects that might be willing to move quicker, said Lloyd. Those “global” implications got more specific listening to Bambrogan talk about his schedule in the media room. Bambrogan is the archetypal badass engineer and wore red suede high-tops that fit the part. From Texas, he was going to Moscow and then Dubai, “where I’ll be meeting with his excellency Sheikh Mohammed.” There was something about Hyperloop Technologies working with Deutsche Bank and SNCF. “If the Sheikh decides —” he said, just before the conversation got drowned out by a camera crew.

Musk’s absence was a constant bummer to contestants throughout the weekend. But he made a surprise appearance after the awards ceremony, compelled to Texas by the #WhereIsElon hashtag that students had started using instead of the official one, #Breakapod. The billionaire showed up in his standard jeans and leather motorcycle jacket ensemble. When Musk paused before speaking, he kept raising the toe of one boot straight up while digging his heel into the stage, giving the effect of a contemplative leprechaun.

Somewhere in the midst of the half-hour Q&A, Musk’s true genius started to reveal itself. A student asked for advice on how to actually build this thing. “If you’re trying to create a company, it’s important to limit your variables,” Musk explained. “I would advocate starting with the simplest use. So I’d probably advocate wheels.” The students cracked up. Here was the man behind the alpha plan telling them that the science they had been chasing after for six months was maybe more like fiction.

Musk echoed Foxx's sentiments about the importance of government involvement and funding. In response to a question from a student about tackling big ideas, Musk told the story of how before SpaceX, he initially intended to send “a small greenhouse” to the surface of Mars, so “we’d have this great money shot of green plants.” An image like that “could get the public excited, and if the public got excited then they would give NASA more money.”

During the Q&A, one of the students also asked Musk how he convinced people that his idea weren’t crazy. “Actually that's generally what they thought,” he replied.