If you blinked, you missed it: President-elect Donald Trump channeling the late Black Panther leader Huey P. Newton just minutes before his swearing-in ceremony. On Inauguration Day, Trump emerged from the Capitol Building, gave a thumbs-up, and then raised his right fist in the air. The incongruity of the fist was plain. Decades earlier, the raised fist was a signal of resistance associated with the Black Power movement. But during his campaign, on Christmas cards and onstage, Trump used the fist as an aggressive symbol of dominance, wielding it throughout his rallies after speeches. And yet the fist was also a focal point at Women’s Marches the next day, appearing on unofficial and sanctioned guides and graphics. One poster, Liza Donovan’s “Hear Our Voice,” depicted multihued female hands gripping a torch made of a black power fist, and another by Victoria Garcia, “Respeta,” echoed the classic feminist logo of a clenched fist inside the Venus symbol. The marchers were openly protesting Trump’s misogynistic behavior and political platform, but they had subtly altered his macho show of strength, too. At the Screen Actors Guild Awards on Sunday night, the cast of the Netflix drama Stranger Things gathered onstage to celebrate a win for “Outstanding Performance by an Ensemble in a Drama Series.” Moved by the passionate anti-bullying message in castmate David Harbour’s speech, several of his co-stars raised their fists to punctuate his words. A clip of cast member Winona Ryder repeatedly raising hers in a comically mechanical way as she made a series of bewildered faces went viral. The raised fist appears to mean everything and nothing at the same time.

When a man as divisive as our country’s current president uses the raised fist as he punches down (at Muslims, Mexicans, women, disabled reporters, etc.) while others use it to express unity, we need to reassess its meaning. The raised fist, once a fixed image of solidarity and strength, has morphed into a nebulous anything. It’s not unlike that ubiquitous “Arthur” meme, easily conveying irritability, mild annoyance, or actual rage. The fist has become shorthand for indignation, whether sincere or ironic, playful or deadly serious.

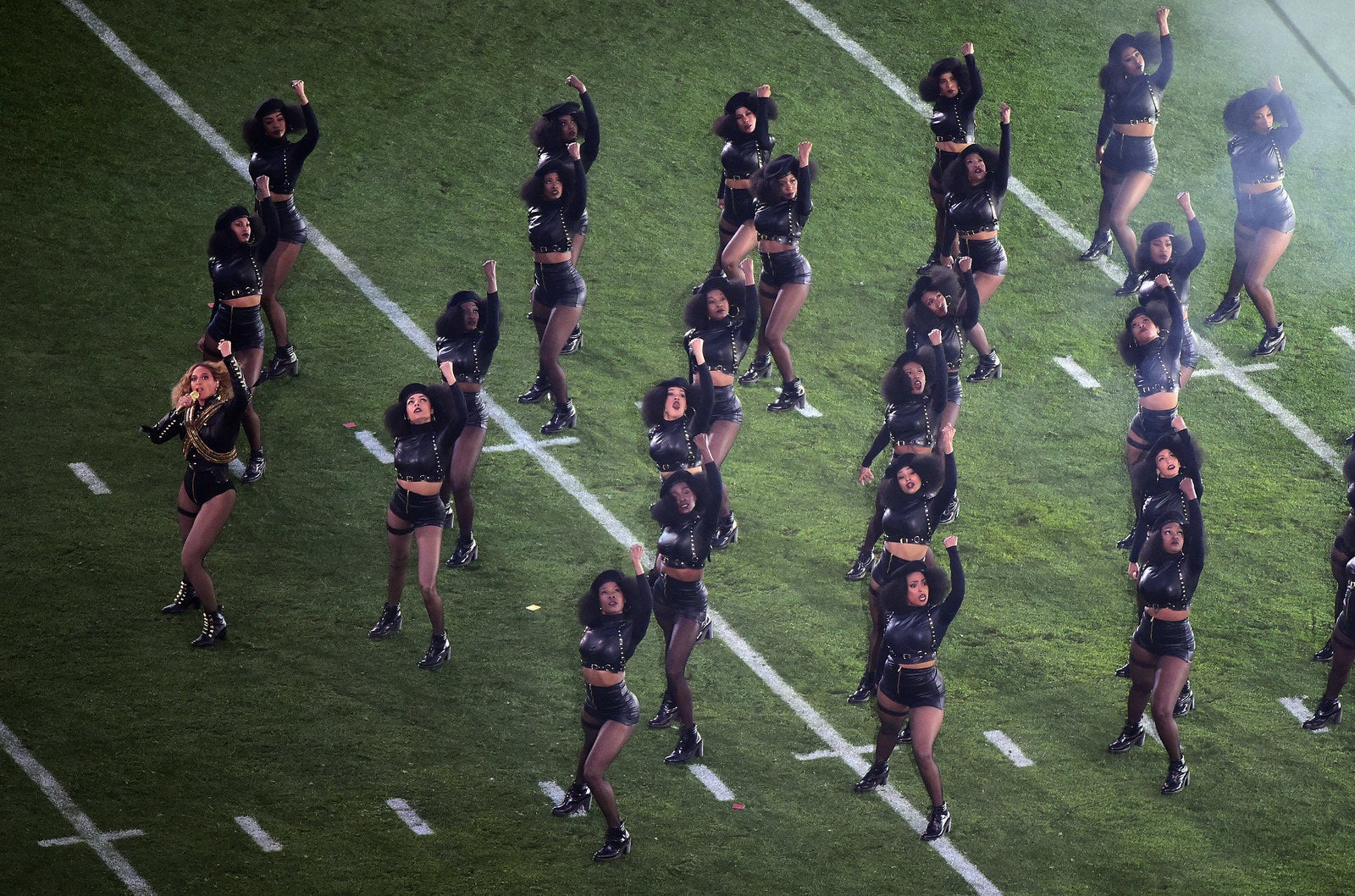

Today the raised fist is as easily found on soapy primetime TV as on a smartphone keyboard. Beyoncé employed it in a music video, Super Bowl performance, and promotional photo last year. The TV show Empire used the symbol in its season opener. FX’s The People v. O.J. Simpson re-created the moment from the infamous murder trial when a juror flashed the black power fist at Simpson in the courtroom. What’s palpable in those scenes is the slipperiness between sincerity and performance, and how both impulses can be evident in the same gesture.

They’re great examples of camp, that ultimate performative mode. Camp, a style and sensibility that emerged from queer culture, has a somewhat slippery definition, but is characterized by exaggeration, excess, affect, and reappropriation. In “Notes on 'Camp,'” Susan Sontag’s landmark writing on the aesthetic, she measures camp “to the degree of artifice, of stylization.” Cultural theorist Andrew Ross, in an essay called “Uses of Camp,” claimed that “camp involves a rediscovery of history’s waste.” The raised fist is not waste in the conventional sense. But it is a symbol that’s been repurposed throughout history by various movements, embedded within visual cultures and discarded, only to be recycled again later. In 2017, the raised fist is where straightforward solidarity and camp collide. And it’s also a perfect symbol of how black American culture is performed and consumed by people both of and outside of the community. Most importantly, it’s about how black Americans, like the meaning of the fist, are constantly redefining ourselves.

Of course, the raised fist is also still a genuine political gesture, as shown by its appearance in controversial moments last year, both in this country and abroad. In May 2016, 16 black West Point cadets faced criticism for raising their fists in a graduation photo that went viral online. At the Rio Olympics, silver-medal distance runner Feyisa Lilesa crossed his fists in an "X" at the finish line to protest human rights violations in his native Ethiopia. On the heels of Colin Kaepernick’s silent protests during the national anthem, fellow pro athletes supported his effort by raising their fists during pregame ceremonies. After the police killings of Terence Crutcher and Keith Lamont Scott, students of the University of Michigan, Michigan State, and the University of North Carolina all used the fist salute. And protesters against the president's executive order banning immigrants from seven predominantly Muslim countries have displayed the raised fist on signs.

Naturally, certain mottoes and slogans from the civil rights and Black Power movements have fallen out of fashion, but the raised fist remains a hugely popular visual signal of defiance and solidarity. The co-optation of the raised fist as a patriotic symbol, winking cultural reference, and even totem of irony show that it is just as much about how we perform protest in the 21st century as it is about communicating resistance.

The early origins of the raised fist hint at how it would be used many centuries later. According to Assyrian Origins, a book on Assyrian art edited by former Met Museum curator Prudence O. Harper, artworks depicting the clenched fist date back to ancient times and were associated with procreation, prayer, and “the manifestation of sheer physical strength.” The raised fist became a go-to symbol for solidarity and strength for labor unions, American leftists, civil rights activists, white supremacists, and the Black Panther Party. In 1971, Ms. co-founders Gloria Steinem and Dorothy Pitman Hughes posed for an iconic photograph in Esquire magazine, raising their fists in interracial solidarity. But arguably its most famous use in the recent American history is by Olympians John Carlos and Tommie Smith during their awards ceremony at the 1968 games in Mexico City. Carlos and Smith’s “black power salute” got them suspended from the U.S. team and turned them into galvanizing figures.

That the Olympians’ 1968 protest has become synonymous with the raised fist is inevitable, given how much it has resonated within black American culture. In ’70s films and TV shows, their real-life act of resistance became a way to subvert the white mainstream and show black pride while calling attention to shallow, romanticized notions of protest culture. In Melvin Van Peebles’ blaxploitation classic Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song (1971), about a guy who saves a young black man from a police beating and becomes a fugitive, the fist is like the jive slang some of its users talk; it shows the thin line between a common cultural expression and a form of comedic relief. On the sitcom Good Times, the precocious, militant Michael Evans parodied a Black Power revolutionary, a performance complete with the clenched fist and impassioned cries of “the man” and “right on” interjected at hilarious intervals. Already then, in the ’70s, a focus on parody and nuance reframed the gesture outside the realm of activism. As civil rights and Black Power organizations were decimated by the FBI’s COINTELPRO, the fist became an inside joke, a way to show the limitations of gesticulation alone.

Depending on their political orientation, black artists in the ’80s and ’90s used the fist to garner appeal. The staged political rally in Public Enemy’s “Fight the Power” music video, with fists rocking righteously throughout, sewed together themes from Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing and real-life instances of police brutality. During the 1991 Super Bowl XXV, Whitney Houston raised her fists triumphantly at the end of her legendary performance of “The Star-Spangled Banner.” Writing for The New Yorker, Cinque Henderson observed, “By making the idea of freedom the emotional and structural high point (not just the high note) of the anthem, Houston unlocked that iron door for black people and helped make the song a part of our cultural patrimony, too.” Her emphatic gesture at the apex of the song, in which she raised her arms in a literal “V” shape, tweaked the raised fist image, if ever so slightly. Comfortable on the Super Bowl’s national stage, she remixed the fist as a vaguely patriotic gesture, a Gulf War emblem of victory.

At the dawn of potential cold wars with Russia and China in the late 2010s, the fist is gotten a campy makeover. The raised fist’s use in Empire and elsewhere in pop culture is a self-referential commentary on how it can be deployed as a political accessory. In one episode of Empire, Taraji P. Henson’s Cookie Lyon emerges from a gorilla costume and shouts “How much longer?” as a crowd lifts their fists in sync at a political rally. Embedded within this campy setup is a surprisingly moving call-and-response on the failures of the prison industrial complex. The show does a great job of pointing at how artifice can blur with meaningful activity.

In 2017, you’re just as likely to see it adopted passionately by a protester as you are to see it — in various emoji skin shades — ironically planted aside a warning to stay “woke,” or politically conscious. You can use the fist to show solidarity while simultaneously undermining it by poking fun at activist posturing. In a viral video, “Hoteps Hoteppin,” writer and comedian Radha Blank raises her fist ironically at the end of a humorous rap song about ineffectual, comically hypocritical black nationalist men. The gesture is just a part of her satire, like the all black-wearing macho brothers dancing behind her in the video. What we’re seeing now with the fist’s use in black pop culture is, in a way, sampled feeling. This usage is akin to what rap producers do with old R&B and soul records. In the hip-hop way, contemporary clenched-fist references show up out of familiar contexts, flush with new meanings. Although Sontag claimed camp is apolitical, the aesthetic shows how bad taste can expose even worse things, like fraught public policy, racism, sexism, and homophobia.

In its various incarnations in black American culture from the ’60s onward, from half-serious nods to fake political rallies, on Empire and in Public Enemy’s “Fight the Power” music video, to memes, to the Beyoncé photo, the fist has been recycled from “history’s waste” into both a conspicuous symbol of resistance and the very failure of resistance measures in this country. Out of the vacuum of black traditional leadership, blasted from FBI’s COINTELPRO, imprisonment, the crack epidemic, and the co-optation by activists into electoral politics, Black Lives Matter eventually emerged. Just as the BLM movement is a paragon of horizontal leadership, a rebuke of the charismatic black male leader model, the super-obvious, always adaptable clenched fist is an unstable symbol of what it means to be critical in our times, turning in on itself and becoming something wholly new.

But, to echo Cookie Lyon, how much longer will the fist serve as a complex symbol of power and performance? Can it continue to be a vital gesture with so much irony in the mix? Camp is partly about excess and exaggeration, about holding the pose too long, or overpronouncing words, or lingering on the awkward. So maybe the long-term use of the fist in black pop culture, across generations, will one day show us again what larger point physical gestures have without vibrant institutional policies behind them. Thinking of the black power salute on the front page of The Black Panther Intercommunal News Service, (the Party's official newspaper), next to its emoji counterpart is pretty disorienting — though for different generations, each version is undoubtedly moving. Maybe now it takes camp to do what courage did then.

In a world that appropriates and mutates every symbol until it’s reduced to a sad, emojified shadow of its former self, how will this vital symbol of strength in the face of oppression (or even total annihilation) retain its intensity? The hope is that it does not become just another peace sign or smiley face, the kind of symbol that adorns Mini Cooper bumpers and preteen earrings. At the Women’s March on Washington, activist and scholar Angela Davis critiqued institutional oppression, uplifted intersectional feminism, and, in a rebuke of Trump’s comments, called for “resistance to the attacks on Muslims, on immigrants [and] on disabled people.” Davis, notably, did not end her speech with the black power salute she helped make famous as a political prisoner in the early ’70s, a symbol that undoubtedly flashed back at her from a sea of handmade signs. Standing to the right of Davis, a sign-language interpreter translated her words into hand shapes. It’s a beautiful moment, watching Davis’s speech stretch out to all the people Trump’s raised fist, and all that it stands for, has tried to diminish.