A week ago I walked through a pall of weed smoke past the rapper Omelly and members of his entourage. They were talking among themselves, scrolling on their cell phones, and dragging on blunts outside of the City Avenue Chili’s Bar and Grill, on the western edge of Philadelphia. I was seriously confused by the scene. Why is he back here? I wondered, barely containing my curiosity as I ambled up the stairs toward the Chili’s ToGo entrance, careful not to gawk at the men.

City Avenue is a long, bustling thoroughfare that’s a part of US Route 1, but its most defining feature is that it serves as the dividing line between Philadelphia and Bala Cynwyd, Pennsylvania. Bala Cynwyd is a small hamlet best known for being featured in M. Knight Shyamalan’s Unbreakable. Chili’s is on the Bala Cynwyd side, and adjoins a shopping center. It wasn’t that Omelly didn’t belong in Bala Cynwyd; it’s just that he seemed too big to be back here in Philadelphia, because he’s Meek Mill’s cousin and closest confidante. Meek now lives primarily in Los Angeles with his girlfriend Nicki Minaj, and s0 — I thought — did Omelly and the rest of Meek’s Dreamchasers crew. Obviously, he could still live here. Or he could be in town to perform or visit family. But...why Chili’s? This is 2016, and hometown stars with access to more glamorous places don’t stick around Philly. And they sure as hell don’t patronize chain restaurants. Long gone are the days when Allen Iverson regularly dropped into City Avenue haunts like Houlihan’s and T.G.I. Friday’s after Sixers games.

Omelly’s presence at this Chili’s was all the more surprising considering Meek Mill’s tarnished reputation in the city and in rap music more generally. You might remember the now-infamous series of events that played out last summer. On July 21, 2015, Meek shocked the rap world when he suggested on Twitter that the reason why Drake had failed to tweet about Meek’s recently released album Dreams Worth More Than Money was because Meek had found out Drake did not write his own raps. What followed was a 10-day frenzy in which Meek and Drake traded insults on social media and a few diss songs back and forth. On the Grammy-nominated “Back to Back,” Drake asked Meek, rhetorically, “Is that a world tour or your girl’s tour?” The single was Battle Rap 101: insults, emasculation, and a reference to the other guy’s girlfriend. After all, it was Nicki Minaj who encouraged Meek to add pop songs to Dreams Worth More Than Money, a gesture Drake referenced on the warm-up diss “Charged Up." Drake capped off the debacle with a blistering performance of “Back to Back” at his own OVO Fest, as Meek memes screened behind him. To make things worse, video emerged of Drake, Kanye West, and Philly hero Will Smith laughing at the memes backstage. Social media users and even corporations joined in on the ragging.

Meek emerged from the fracas as a living, breathing “Crying Jordan” meme. His rising profile, aided by glowing coverage in such publications as The Fader, which had once called him “one of our generation’s greatest street rappers,” dipped following the rap beef fiasco. Rap fans simply didn’t seem to care about old-school notions of authenticity, as Complex’s David Drake pointed out in his essay “No Idea’s Original: Authenticity in Rap Is a Myth.” On “Wanna Know,” the Drake diss which he released one day after “Back to Back” and six days after “Charged Up,” Meek sounded truly befuddled by the state of the rap world: “Shit gettin’ different out here, it’s gettin’ spooky.”

Meek emerged from the fracas as a living, breathing “Crying Jordan” meme.

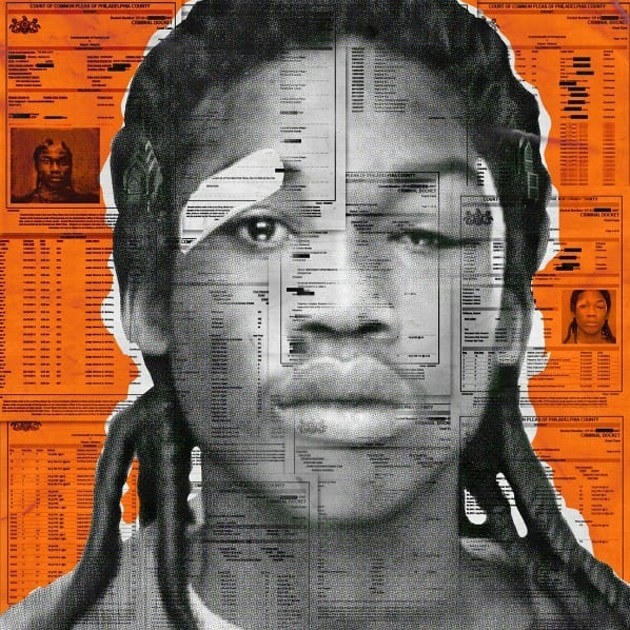

Little did he know, his reputation would take another hit. In December 2015, Meek was found guilty of violating the terms of his parole. The details that emerged during the hearings, like the fact that he allegedly submitted cold water as a urine sample, and that Drake fans called the prosecutor begging her to arrest Meek, further fueled the public’s mockery of the rapper.

As a result of the parole violation, Meek spent a little more than three months on house arrest. It seemed that his time spent lying low was good for him; in May, Dreams Worth More Than Money won the 2016 Billboard Award for Top Rap Album. Then the drama returned. In September, rapper The Game called out Meek for allegedly telling cops that The Game was involved in the robbery of singer Sean Kingston’s jewelry at a Miami nightclub. The Game released two diss singles, “92 Bars,” and “Pest Control,” ridiculing Meek for low album sales and continuing the emasculating theme Drake established, referring to him as “Meesha,” and alleging that he won Nicki Minaj’s heart by FaceTiming her while her ex Safaree had sex with other women. This all coincided with The Game’s intense Instagram campaign marked by jokes, homophobic taunts, Nicki Minaj barbs, and theatrical threats.

Philly rapper Beanie Sigel, who had appeared on Meek’s response track “OOOUUU (Remix),” eventually attacked Meek, too. Sigel went on The Tax Season podcast and ranted for two hours, claiming that Meek was a stingy, phony gangsta rapper who had no name in the street. It was a rebuke of the highest order, with Sigel even going as far as to say that he ghostwrote for Meek and his team, and insinuating that a romantic relationship between Nicki Minaj and Drake prompted the June 2015 beef. Sigel also released three diss tracks, including “Good Night,” where he raps, “I’m the dad you never had/what’s your problem n-----, I’m like your father figure.” Meek responded to Sigel’s tracks with dismissive Instagram posts, but did not release any music aimed at him, save for a few veiled shots in a freestyle on Funkmaster Flex’s show.

In the Chili’s parking lot not far from where Omelly and company stood, there was a car parked at an oblique angle, which may or may not have been a part of the Dreamchasers convoy. The car was situated so that it could surveil the whole lot at once, giving the impression that Omelly and co. were at least aware of the security issues that could arise from their presence there, or someone else was. A month earlier, in September, Omelly and other Dreamchasers affiliates responded to The Game’s taunts with diss verses and Instagram provocations: pictures with guns and post-ups in front of cheesesteak joints. Then one of Meek’s associates sucker-punched Sigel at the Philly stop of Diddy’s Bad Boy Reunion Tour. Tensions were so high that Philly rapper AR-Ab, who was name-checked in Drake’s “Back to Back” diss, suggested holding a citywide mediation session between “all the bosses/men of honor and men with power” in Philly.

The strangeness of Omelly being back in Philly at a chain restaurant of all places was not lost on the Chili’s cashier either. As I was being rung up, I felt the wind and the smell of weed and barbecue mixing, and before I knew it Omelly was behind me. “Yo what’s up,” he said to the cashier, and gave him a handshake. He asked for directions to the bathroom and then turned the corner. “Yo, that’s crazy,” the cashier deadpanned afterwards, swiping my debit card. “What, Omelly?” I asked. “Yeah,” he said, and went to retrieve my food from the kitchen. It seemed like we both wanted to know: Why was he back here, and by extension, was Meek back here too?

I found myself thinking about that same question while listening to DC4, Meek’s latest and highly anticipated new mixtape which came out last Friday. After less than stellar showings in three separate rap battles, the question of why Meek Mill is still rapping is a relevant one, if claims from NBA players, rappers, and several think pieces are any indication.

Despite all of the drama, hopes were high for DC4. There were expectations that this mixtape would be redemptive, that it would re-establish Meek’s musical credibility and restore his name. DC4 is the fourth installment of his critically-acclaimed Dreamchasers series, which began in 2011. In addition to being a sequel to Meek’s other mixtapes, DC4 is also a send-up of the trap genre. It traffics in the genre’s major themes: bleak, bleating auto-tuned blues, heavy drug use, and street tales, but adds something more conceptual, though not explicitly so. DC4 is like a trap spaghetti western, fixated on revenge and punctuated by anthemic, operatic instrumentals that sound in places like Ennio Morricone overlaid with 808 drums. On DC4’s 14 tracks, Meek’s out to settle scores against vague forces while creating a valiant musical one of his own. Throughout the mixtape, his trademark yell transforms into a war cry. “Member they said I was done-done/Fuck, they ain’t know I’m the one, one,” he raps on the first track, laying his claim for vengeance. “On the Regular” opens with gunshots over an orchestral overture. The song follows in the tradition of Meek’s other album-openers by matching epic samples, in this case Carl Orff’s “O Fortuna,” with big boasts. “Sell a lot of dope, dodge a lot of cases/sticking to the basics/Rock a lot of chains, do a lot of things/Bottle by the cases,” Meek trumpets. “I do not see no competitors,” he gloats, “hatin cause we got ahead of ‘em.”

The swaggering continues on the bombastic “Blessed Up,” which has Meek marveling at his survival. At the beginning of the song, Big Meech of the infamous drug-trafficking organization Black Mafia Family (BMF) gives Meek a pep talk from prison. “Be who you are. You ain’t got to impress nobody,” he says, feedback from the phone’s connection crackling on the line. “You’ve been tested and you stood up, and you still standing up.” Meech delivers the album’s underlying theme as sweeping instrumentation soars underneath his monologue: “I don’t need you to be no motherfucking gangster for me. I need you to be a man.” DC4, like westerns, rap music, and many other products of American culture, is obsessed with manhood. The attacks by Drake (“Is that a world tour or your girl’s tour?” “Shout to all my boss bitches wifin’ n-----s!”) The Game (“Meesha,” homophobic taunts on “Pest Control”) and Beanie Sigel (“I’m the dad you never had,” the Nicki-Drake cuckolding allegations) hover over the tape. Big Meech’s prologue affirms Meek’s street cred, and acts as a counterpoint to the emasculating digs Meek’s faced in the last year-and-a-half.

The question of why Meek Mill is still rapping is a relevant one, if claims from NBA players, rappers, and several think pieces are any indication.

On “Offended,” Meek and featured artists Young Thug and 21 Savage anchor all of the tape’s themes by tweaking weird slang and trap tropes (eccentric ad-libs, distorted snares) to shout out shadowy foes. Young Thug twangs atop an old-time piano and 808s, spouting anachronous couplets from a pretend stallion: “I’m too high-horsed for asphalt/therefore I’m in clouds from day to dark” and out-of-left-field lingo like “I’m in Piccadilly’s with your missus n----.” (Piccadilly’s is a cafeteria chain, but the word sounds marvelously archaic in his mouth.) Coupled with Thugger’s rangy verbal tics, the anarchy and macho posturing in Meek’s verse complete the western theme as the rapper threatens some unnamed enemy, claiming he’ll “smoke you wherever we see you at.”

“Blue Notes” is the album’s centerpiece, and it’s also its heart. The song begins cinematically, with an extended intro of an organ and a few haunting, bluesy guitar licks. Then a sample of English guitar maestro Snowy White sings, “this is my blues/cause I’m back down on my own again.” Soon after, the beat drops. “Was it the money that made me a savage?” he asks. There’s a pervading sense of sadness as he explains his woebegotten choices. As White’s plaintive singing stops, so does Meek’s voice, briefly. Then he starts back up, raging against the pain of abandonment and faux friends. I realized then that maybe Meek’s tendency to yell, invariably, on 99% of his songs, is a way to beat back silence, or the uncanny quiet that makes regret rattle in the brain. On DC4, Meek’s more comfortable with his own silence; “Blue Notes” and the end of both “Blessed Up” and “Offended” feature little extended instrumental breaks that play after he’s done talking. That kind of thing is rare for Meek, who has in the past insisted on filling every second of space with shouts and loud ad-libs. DC4 plays with sonic dissonance in a way that reflects the jarring circumstances in its creator’s life.

The mixtape is also an act of cognitive dissonance. On the one hand, it’s firmly about redemption. Although on the other, he doesn’t directly assail anything or anyone. The consequence of those contradictory impulses is that DC4 feels like the setup to something grand that ultimately does not come. The record feels like a Clint Eastwood flick that doesn’t hit all the right beats. DC4’s arc is like a Sergio Leone film that’s just scenes of partying at saloons interspersed with clips of the hero outcast on the outskirts of town, without the climactic gunfight everyone expects.

DC4 feels like the setup to something grand that ultimately does not come.

In a somewhat ironic note, just as most rap fans concluded that they didn’t care about the Drake ghostwriting accusations, DC4 proves that Meek does not really care to address many of the controversies that have derailed his career and personal life, and that have also delayed this project outright. Although he responded to the Drake feud with belated diss songs on the EPs 4/4 and 4/4 Part 2, on DC4 he doesn’t address any of the feuds directly, which proves disappointing given the long wait. He just goes back to basics, to quote a line from “On the Regular.” His avoidance of musical conflicts is not surprising given his recent track record of halfheartedly engaging with his rap beefs or the ideas that undergird them. It’s just odd that given the high stakes, he’s chosen to disregard major career events to offer a portrait we’ve mostly seen before. His ambivalence toward direct attacks parallels the purpose of the spaghetti western, which film critic Pauline Kael claimed “eliminated the morality-play dimension and turned the Western into pure violent reverie” in her book The Age of Movies. DC4 avoids the morality of Meek’s beefs by refusing to get mired in the details. It doesn’t matter who’s right or wrong, now. On the mixtape Meek Kanye-shrugs at the whole drama while insisting he’s triumphed over it all.

DC4’s lyrical content is certainly redundant. You might wonder, after all that’s happened in his career since DWMTM, why he’s retreading the same old lyrical terrain: women, expensive jewelry, luxury lifestyle, brags about Nicki Minaj, nostalgic references to his tough upbringing, and street life. The answer might be because it’s easy to do, fans love it, those topics form the foundation of his artistry, and it’s propelled DC4 to the top of multiple digital charts. But the less obvious one is that Meek is testing the waters of a new concept, and a radical one at that: the notion that rap is post-beef. If Meek Mill, the man who for months was the internet’s joke, can fail to really engage in beef, and more importantly, survive the onslaught, that’s truly extraordinary, and hasn’t been done before. Now that Meek is standing again, as evidenced by DC4’s early commercial and critical success, it appears that beef may not have the same power to sell records (The Game’s recent beef-fueled album 1992, only sold 32,000 records its first week), and end careers. Meek Mill is no Ja Rule, even though he faced arguably stronger forces than Rule did in the early 2000s, when he went to war with 50 Cent. Meek has weathered hit diss records and the scorn of much of the internet and the original rapper-slayer 50 Cent, who proclaimed Meek’s career “over” earlier this year after the two exchanged shots on social media. Meek’s reluctance to directly attack his foes is a bold statement that’s made even more ironic given his history, and the infamous tweet that precipitated his downfall. By ignoring controversies, he’s basically saying that gimmicks and faux-feuds don’t matter, only music does.

It appears that beef may not have the same power to sell records.

DC4’s offbeat western tropes also allude to the strange place hip-hop is now. At the moment, hip-hop appears to be at the cusp of a new frontier. There are new rules to contend with, and anything seems possible. Record companies are a dying breed, streaming is the dominant mode of consuming music, Kanye West regularly complains of the Apple-Tidal wars, to the point that one of the most treasured alliances in the genre’s history, West’s partnership with Jay Z, appears to be on the rocks. (It’s rumored that Jay Z chose not to appear on Drake’s “Pop Style” out of respect for Meek Mill, who’s managed by Jay’s Roc Nation.) Rap beefs don’t have the same impact as before, and podcasts, not diss songs, are where folks feel most comfortable airing grievances. Certainly, Meek’s decision to not really address the beefs in music, opting instead to go on the Tax Season podcast in an episode that aired Monday, further illustrates this break from tradition.

From listening to his podcast interview, it was clear that Meek’s split from conventions upset Beanie Sigel. Their feud has rippled across the city’s rap scene. After The Game’s disses galvanized the city’s rappers, Sigel’s attacks fractured alliances, as Meek explained on Tax Season. It was not just a rap beef, or a generational divide: It was a battle for the soul of Philadelphia’s rap scene. The city is known for gangsta and battle rap, both hyper-masculine, macho subgenres. Recent events have called into question Philly’s rap identity. Does it just want to be known as a place that breeds battle-rappers when the commercial appeal of such artists has begun to diminish?

Before Meek Mill was sentenced back in February, he told his judge that he was a different man. "I just want to ask you for a chance to turn that corner and be a changed man," he said. "You said you saw something in me ... I want to prove you right. I believe I can be the bright star you intended me to be." It’s too soon to tell if DC4 will redeem him. Meek is a prodigal son, living in LA now, but forever fond and partial to his hometown and the streets that made him. To me, that’s what that Omelly sighting signifies — Meek’s cousin chilling in the Chili’s parking lot, likely aware of the heat his cousin had in his hands.