Brain-burrowing worms, flesh-eating bacteria, and microbes that short-circuit the nervous system are just some of the stowaways that Americans picked up on their travels last year.

“Food and drink can be a common source of parasitic infections,” James Maguire, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and senior physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, told BuzzFeed News. “Even here in the US, unclean drinking water can lead to giardiasis or cryptosporidiosis,” he said. Typical holiday behavior — eating at unfamiliar locations and spending a lot of time outdoors — increases the chances of picking up parasites.

US residents took an estimated 1.7 billion vacation trips in 2016. The most common travel illnesses are gastrointestinal infection, according to the GeoSentinel Global Surveillance Network, which tracks sick Americans on the move.

Between 2000 and 2012, 58% of international travellers returned with a stomach bug, 18% had fever-inducing infections like dengue and malaria, and 17% came back with a skin infection, sometimes by a parasite.

But rarer, more exotic causes are always a possibility. At the doctor’s office, returning travelers will be asked about transport and living conditions, water and food sources, and bites and the bugs that caused them. “You put them into the equation,” Maguire said.

Here are five real-world stories of parasites mystifying doctors before being caught out:

The brain-burrowing nematode

Earlier this year, a California couple returned from a trip to Maui with what they thought was a mild case of flu. But when Ben Manilla, a professor at UC Berkeley, found he couldn’t move his arm to write on a whiteboard, he and his wife got tested. The diagnosis was “rat lungworm” — a parasitic infection caused by a nematode that had lodged in the brain.

“That’s way on the unexpected list,” Maguire said.

Hawaii has seen an uptick in these infections since the 2004, when a species of snail that plays host to the nematode was introduced on the big island. The nematode, a kind of primitive worm, spends part of its life in these snails, and part of its life inside the brains and lungs of rats.

Unless they encounter a human, that is. Slug slime tracked across salad leaves, which are eaten without being properly washed, or parts of an infected slug chopped up into salads or a smoothie, are the most common sources of the infection in people, Sue Jarvi, a professor of pharmaceutical sciences at the University of Hawaii at Hilo, told BuzzFeed News.

Nematode larvae are absorbed from the gut into the blood, and course through the body until they lodge in the brain. The worms then grow, creating a cavity for themselves. One reason why the infection is hard to diagnose is that symptoms can vary: from excruciating phantom pain in the limbs, to mild flu-like signs, to meningitis. A brain swelling triggered by the worm is usually fatal.

The parasite is most at home in the balmy subtropics, including Asia, Australia, and the Caribbean and Pacific Islands. But recent reports have recorded infections in Texas, Louisiana, and Florida too. This year, a University of Florida team wrote that that the nematode had established itself in the state, and, “alarmingly,” even in regions with cooler temperatures than would be expected for this species.

The brain-eating amoeba

In 2013, an Arkansas tween became only the third person known to the CDC to survive infection by the single-celled Naegleria fowleri, an amoeba that drills into and infects the brain.

The single-celled organism lives in warm freshwater lakes and rivers. It enters the body through the nose, then heads straight up the olfactory nerve to the brain, where it triggers an inflammation and begins destroying brain tissue. Most reports of the condition trace it back to a swim outdoors.

This parasite is rare but deadly: Between 1962 and 2016, the CDC recorded 143 cases of infection, up to eight a year, almost always fatal. Doctors believe the Arkansas schoolgirl may have benefited from an earlier-than-usual diagnosis and treatment.

According to the CDC, the amoeba can’t infect someone who drinks contaminated water. But in 2011, the amoeba killed two people in Louisiana who used tap water in neti pots to irrigate their sinuses. Water samples in both of their households contained the amoeba, tests found.

Symptoms begin with fever and nausea, and as the infection progresses, it produces hallucinations and, eventually, a coma. The CDC has recorded only four US survivors to date.

A traveling Floridian hiking in New Hampshire returned to Miami with blisters earlier this year. Within days, he was in a coma in the hospital where doctors tried to save his life by cutting off chunks of flesh off his legs.

The young man had picked up one of a collection of “flesh eating” bacteria that cause “necrotising fasciitis.” The most common of these culprits is Group A strep, a relative of the bacteria that causes strep throat.

Each year since 2010 there have been between 700 and 1,100 cases of the infection, according to the CDC. These usually occur when bacteria enter and infect an open wound.

In these rare but serious cases, the infection can have deadly effects: Bacteria kill swaths of tissue and muscle by releasing a toxin.

(The rapid and gruesome progression of this parasite has made it a hit in medical dramas: In Grey’s Anatomy, a woman picks up the bacteria on her honeymoon and narrowly avoids an amputation; in House, Hugh Laurie’s character makes at least one diagnosis of the disease.)

Symptoms include chills and fever, black spots or swelling on the skin, and a sensation that resembles muscle pain. The CDC recommends staying out of hot tubs or swimming pools if you have an open wound, and keeping those wounds clean.

The zombie protozoan

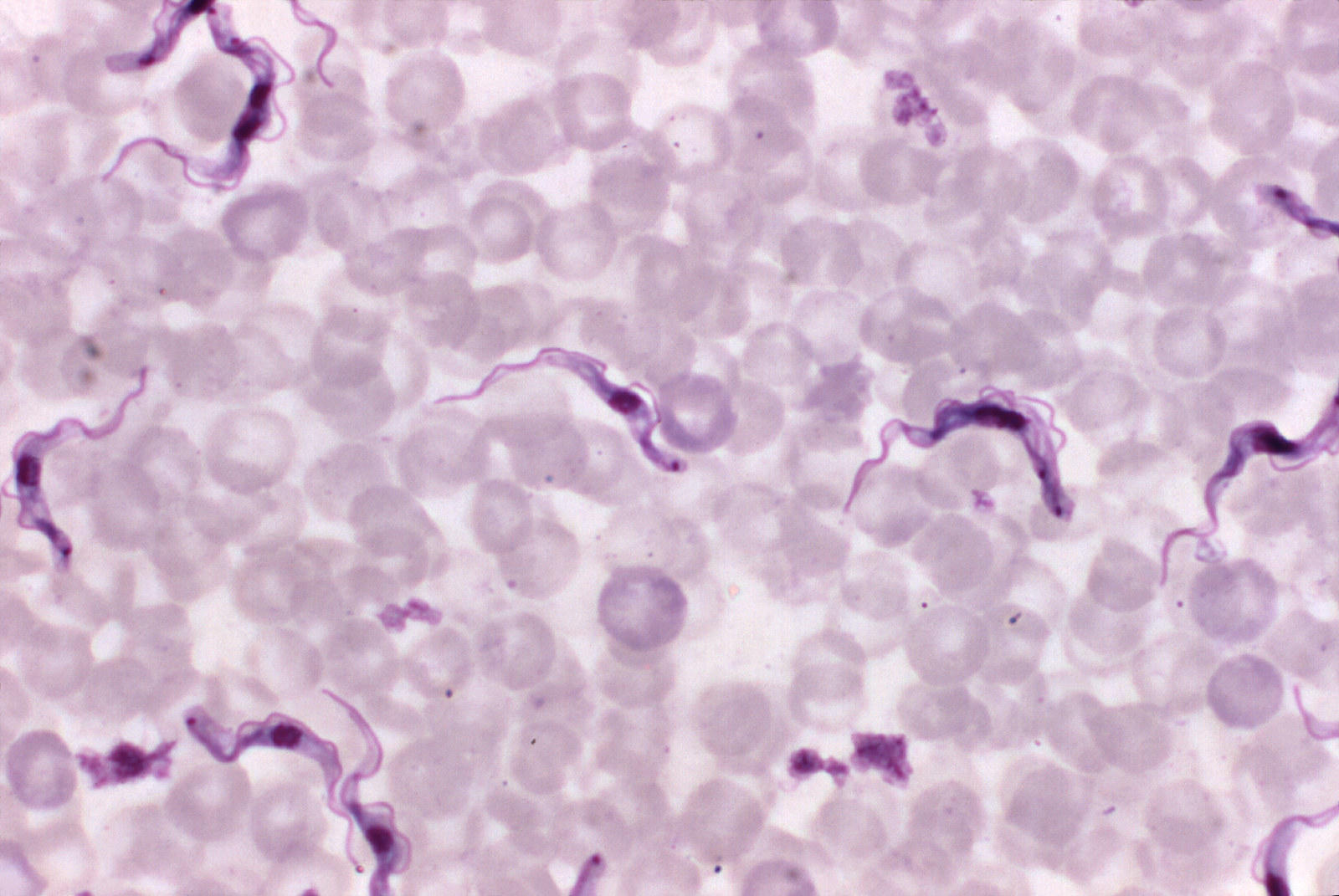

Public health agencies are winning a battle on “sleeping sickness,” or trypanosomiasis, in the 36 countries in sub-Saharan Africa where it is endemic. But the odd traveler still occasionally falls prey.

“Any time there’s a case of sleeping sickness — that’s memorable. It’s very unusual in travelers but it does happen,” Maguire, of Brigham and Women’s, said.

About 98% of those are by caused by the parasite Trypanosoma gambiense.

Tsetse flies are carriers of the parasites, and they inject them into the bloodstream of any animal — including humans — they bite. From the bloodstream, the parasites invade the central nervous system and cross the blood–brain barrier.

The symptoms unravel over years. Several months in, they trigger headaches and muscle pains. Eventually, the protozoan’s takeover of the central nervous system results in personality changes, trouble with balance, and possible paralysis.

Ignoring the condition can result in coma, and eventually death. But depending on the stage of the infection, treatments differ: Meds for both stages are available in the US.

The hookworm in hiding

Two weeks after a beach vacation in the US Virgin Islands, a 45-year-old woman reported an itchy rash on her knee. About two weeks in, the rash had evolved into zig-zag bumps.

“Those lines you see, those wavy lines, that is the parasite burrowing. If you saw a time-lapse, one edge would move over time,” Chaiya Laoteppitaks, an emergency physician at Thomas Jefferson University Hospitals in Philadelphia, who recorded this case in The Journal of Emergency Medicine this year. “It looked like a textbook example.”

It was a case of hookworm infection, caused by one of a family of wormlike parasites that usually live in dogs and cats. Excreted in animal poop, the worms are on the hunt for the next host, and can enter the skin of a person walking on the beach or lying in the sand. They can’t get much farther, though, so show up like a stray strand of reddish-purple wool just under the epidermis.

The symptoms of the parasite are gross, but mild: itching, some soreness, light swelling. Treatments exist, but some parasitologists suggest waiting it out about three months until the worms die, after which they will simply waste away and disappear.