Puerto Rican families who fled to New York City in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria and have decided to stay permanently are now faced with the difficulties of finding places to live and restarting their lives — as government agencies fail to offer long-term solutions.

Watching the situation in Puerto Rico has been disheartening for many of the families. Electricity is still unreliable. Hundreds of public schools will be closed in the coming years. Public utilities are in debt. Universities are in crisis. The unemployment rate is 10.3%, almost triple the US national average. And a new hurricane season is approaching.

The families who decided to stay in New York City and other places with affordable-housing crises, like Orlando, have found themselves caught in the confusion and uncertainty of government bureaucracy.

Desiree Cancela, 33, left Puerto Rico on Oct. 18. Her apartment was damaged and she lost her job at Cravings, in Aguadilla. She told BuzzFeed News she's planning to stay in New York with her two children, 1 and 2 years old.

"I made the decision because my kid who has special needs has to have his medicine and physical therapy. I was stuck without a job; I couldn’t pay the rent," Cancela said. "My son also has bad asthma and we couldn’t access a hospital easily ... I was frightened."

"After perfecting my English, I'm thinking of studying nursing," she said.

But first: Cancela needs to find a permanent place to live. Through FEMA's Transitional Sheltering Assistance program, or TSA, she and her children have been living at the Rodeway Inn in the Bronx for the past four months.

Cancela’s family is one of 140 in New York state relying on FEMA's last-minute extensions to the shelter program each month. Their final extension expires at the end of June, and it’s not clear how she’s going to find and afford a place when the program ends.

As of this week, 2,135 Puerto Rican families across the country are relying on TSA for housing. Of those, 1,489 are in states outside Puerto Rico. And anyone who wants to stay is facing that same end of June deadline.

"Many of us have been here for more than six months now. Many of us have jobs; our kids are in schools," said Andrea Tejeda, 25, who left Puerto Rico for New York with her 4-year-old daughter Jadieliz on Dec. 14. She was frustrated with a lack of electricity and even water in her San Juan neighborhood.

Since arriving in New York City, she's started working at the City University of New York as a college assistant. Her daughter has been accepted into Manhattan Charter School 2, on the Lower East Side. But without housing, she's not sure how she's going to make their new life work after the FEMA program expires.

"They’re hoping we get tired and just leave," she said of the government agencies she's reached out to. She's made multiple trips to the offices of Homebase, New York City's homelessness prevention program, but says she's been shuffled to different agencies, none of which have given her concrete guidance on how to solve her housing problem come July.

She said she went to the New York City Housing Authority's downtown office on April 17 to ask about Section 8 housing, but said she was told to "go back to Puerto Rico" by a supervisor there.

"I went to NYCHA and they said, no, Puerto Rico is going to be fixed and they don’t even have space for New Yorkers, never mind us Puerto Ricans," she said.

“I partly feel discriminated against because it seems like they don’t want to help me because I’m Latina and of Puerto Rican origin,” she said.

An NYCHA spokesperson told BuzzFeed News they will investigate the incident. “This is absolutely unacceptable and goes against our goal to provide safe, clean and connected communities," the spokesperson said in a statement.

Tejeda also reached out to the federal department of Housing and Urban Development, or HUD. Officials there told her to go to a homeless shelter, which seemed to her like a step away from trying to find permanent housing.

"I just want a stable place for my daughter to grow up. We’re just shuffled from place to place," she said. "We’ll wait and see what happens; we’re still waiting to see what will happen to us."

A spokesperson for HUD, Brian Sullivan, said Tejeda may have been directed to a shelter if she said she was in danger of becoming homeless.

In the past, FEMA has funded a program allowing the federal government to work with local public housing authorities after the funds for TSA — the program that ends in June that has the Cancela and Tejeda families worried — have expired. This secondary program is called the Disaster Housing Assistance Program, or DHAP.

DHAP gives federal funds to local public housing authorities to provide security and utility deposits, lease termination payments, and other housing assistance for people, usually for up to 18 months. A caseworker helps the applicant through the process.

"It was essentially a federal government recognition that it's going to take people a while to get back to their lives and they need help for a longer time than these temporary shelter programs really are designed for. You can’t sustain people in hotel programs for years," Sullivan said.

The program was born out of the Katrina, Rita, and Wilma disasters of 2005. After Katrina, nearly 37,000 families had housing assistance through DHAP, at a total cost of $552 million.

After Hurricane Ike in 2008, 27,000 families were enrolled — FEMA paid a total of $281.3 million for that program. It was extended "due to ongoing need," according to HUD, and ran for more than three years after the disaster.

But after Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria pummeled the US 2017 — the program isn’t being used.

One reason, said FEMA spokesperson Ron Roth, is “the availability of other housing options” for Maria survivors. For people staying in New York City, that idea is laughable.

Another reason, Roth said, is a 2011 Inspector General report that found the program didn’t collect data well enough to determine how effective it is — even though the program was used in the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy, a year after the Inspector General report was released.

Roth said that FEMA and HUD are using other programs which “are better able to meet the current housing needs of impacted survivors.”

Some families are getting rental subsidies that require them to find housing themselves. He said that across the country, 126,939 households have been provided with this rental assistance — totaling more than $108.2 million. The rental assistance program is available until 18 months after the hurricane, so March 20, 2019, or earlier if a family reaches the $33,300 cap on all repair and rental assistance-related costs. About 200 other families are housed in other FEMA housing lease programs.

Citing privacy laws, FEMA said they could not disclose where in the country the families using these programs are located.

But for survivors with extremely low incomes in places like New York City and Orlando — which have affordable housing crises — receiving some rental assistance doesn’t give them a way around the shortage.

For local officials, there is no easy solution to housing newcomers when there are already hundreds of thousands waiting for a stable place to live.

New York City has 175,000 public housing units in total — with a waitlist of approximately 230,000 families. It also has a maxed-out waitlist for Section 8 vouchers, a separate affordable housing program.

Asked what specifically the city is doing to help hurricane evacuees find permanent housing, a spokesperson for NYC Mayor Bill de Blasio said, "We’re working on it."

Just 7.9% of recently available apartments in New York City are affordable for extremely low-income families — earning no more than $24,500 for a family of three, according to NYU's Furman Center for Real Estate and Urban Policy. Just over 40% of recently available apartments are affordable for low-income families that earn no more than $65,250 for a family of three.

For comparison, the median household income in Puerto Rico is $19,606, according to the most recently available census data.

"The numbers are really very disheartening," said Vicki Been, faculty director of NYU’s Furman Center for Real Estate and Urban Policy, who served as commissioner of New York City's Department of Housing Preservation and Development from 2014 to 2017. "It's not easy to find an apartment in New York City at many income levels, but if you are at those very low income levels, it's really, really hard."

"It's not easy to find an apartment in New York City at many income levels, but if you are at those very low income levels, it's really, really hard."

Alternatives are scarce. Some advocates say the city should make use of empty buildings to house Puerto Rican families in need. But that has a raft of issues — primarily that most vacant buildings are owned by someone.

New York state’s response has been mostly to pressure the federal government to provide more resources. The state also provided information to newly arrived Puerto Ricans at JFK airport in the immediate aftermath of the disaster, like information packets with a link to a state-run website with affordable housing listings.

A spokesperson for New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo, who has visited Puerto Rico several times since September, said the governor has advocated for FEMA to indefinitely extend the TSA program and "offer other interim assistance to help displaced families."

"Nearly 250 days since Maria, no one should be without a roof over their head — our Puerto Rican brothers and sisters deserve better," the spokesperson said.

Mayor de Blasio has acknowledged that housing is a major challenge for Maria survivors. In the immediate aftermath, he said that the city could not help place people, and that Puerto Ricans should only go to New York City if they had family they could stay with.

But even that is not a viable long-term solution for some people. Carcela stayed with elderly relatives for three months before moving to the TSA-sponsored hotel. She had to leave because they were in public housing specifically set aside for elderly residents, and the neighbors were complaining about her toddler being noisy.

Families who spoke to BuzzFeed News said the city had initially been helpful to them when they arrived. On Oct. 19, New York City set up a hurricane service center in Harlem, a one-stop shop for people arriving from regions affected by hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria.

"I spoke to an attorney there who explained my rights," said Carcela, who said FEMA has closed her case twice because she wasn’t on the island, but reopened the case after the attorney called them in January.

But since the city closed their assistance center down on Feb. 9, Puerto Ricans still trying to apply for housing, welfare, and FEMA aid were left without a central place to go to be guided through processes they're not familiar with. They're instead relying on volunteers, people who were already part of New York's Puerto Rican community — like Soldanela Rivera, who has been supporting people who feel disconnected and overwhelmed by the systems they're trying to navigate.

"These are my people. This is just a terrible, terrible calamity and the incompetence and racism they're dealing with on top of that," Rivera said, adding that the city's resources center closing has been a blow to the community. "So again the people with the least resources, the least time are picking up the pieces."

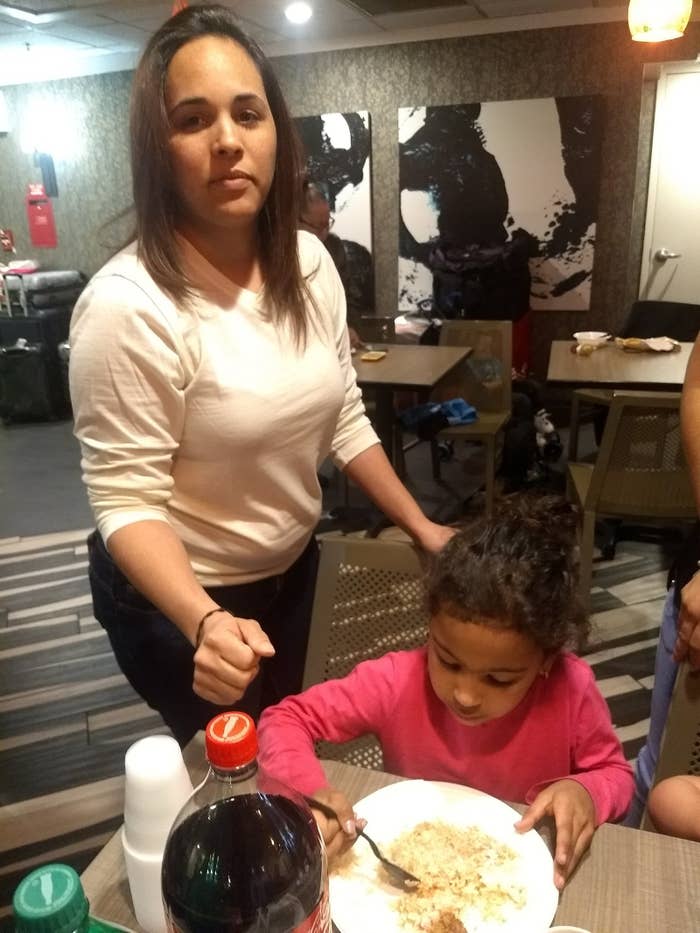

At one recent Sunday meetup, Carcela, Tejeda, and a dozen others gathered in the modest lobby of the Midtown Convention Center Hotel in Manhattan, where some of the families are staying, sharing lunch and trading stories about the past eight months of their lives.

"Puerto Rico has become more hostile," Tejeda said. "I lined up three to four hours to get water, only to reach the front of the line, and there was no water left. Food and water were crazy expensive. And their availability was like, one day yes, one day no, one day yes."

Another woman, Gloria Martinez, 52, said she left her home in Toa Baja, in the north of Puerto Rico, on Jan. 9. She said she still didn't have electricity by the time she left, and she was worried about the effect of the instability on her 17-year-old daughter, Joanelly.

At the same time, her husband had become abusive and she was fearful for her and her daughter's safety.

Joanelly is enrolled at the High School of Hospitality Management in Midtown Manhattan, down the road from the hotel they're living in. Martinez said her daughter has good grades and wants to apply for colleges outside Puerto Rico, because there are more opportunities. Martinez is studying English to be able to apply for jobs — she has a degree in information systems and a master's in information security and fraud investigation.

"I will be at ease a little emotionally when we have a permanent place to sleep, when I know we won't be on the street. And where my daughter is safe, which is the most important thing for me," she said.

Martinez is also trying to find a place to live after the TSA program ends. She's been to Homebase offices several times, she said, and has applied for rental assistance through the city. She received an initial $500 emergency payment from FEMA and approval for the TSA program.

"We came here with certain hopes,” said Martinez, “and the reality of the situation has been quite different.”