PITTSBURGH — It’s about 10 minutes into my ride in one of Uber’s mostly autonomous vehicles, and I’m starting to feel a little carsick. The car suddenly hits the brakes — hard — and the audio equipment I’m using for this story goes flying off the seat.

“I don’t know if you saw, but a motorcycle kind of unexpectedly turned in front of us, right? And so the car put on its brakes,” says Jon Thomason, Uber’s head of self-driving software. That jerky, nervous braking, which I experience many times during my hours riding in the ride-sharing company’s robot cars, is by design. Self-driving always seemed like a futuristic ideal only possible in movies; I never imagined the reality of riding in a car that could drive itself would be slow and boring, and kind of make me want to puke. But logging millions of uneventful, nausea-inducing miles is what it’ll take for Uber — and all of the other tech companies and automakers working on the same thing — to make their vehicles fully driverless, and so Uber is prioritizing keeping riders alive, even if it makes them queasy.

“We’re going to opt for being safe over personal comfort at first,” says Thomason, who joined the ride-hail company in September in the midst of a year of scandals, including the departure and replacement of CEO Travis Kalanick and a contentious trade secrets lawsuit with Alphabet over the very self-driving technology he’s working on.

Despite all the turmoil — and the legal threat to its autonomous car tech — Uber is pushing forward with its robotic ambitions. The company has four sites in Pittsburgh, including a high-tech 42-acre mini city to test its vehicles, along with additional campuses in San Francisco, Toronto, and Phoenix under Uber ATG (Advanced Technology Group), a division dedicated solely to its self-driving efforts. There are over 200 self-driving Ubers already being tested in the wild, hailable in test cities by anyone with the app; these cars can drive autonomously but are designed to have a vehicle operator in the front seat at all times.

The company doesn’t mind taking paying customers on a ride that’s not super smooth right now, because the more miles logged and data captured, the faster the cars improve. And with several companies — including Apple, GM, and Ford — vying to win the market with the same technology, the race is on to be the first company to get autonomous cars on the road, en masse, in the real world.

We continue driving around the track, a testing and teaching ground for Uber’s self-driving sensors, prediction models, and pedestrian detection engines. The site, located about 15 minutes south of downtown Pittsburgh, is where Uber puts its self-driving software through the wringer and teaches its vehicle operators how to watch over a car that can drive itself.

Uber’s test track, called Almono, looks like a mini city. It has roundabouts, working stop lights, streets lined with parked cars, shipping containers posing as parked cars (they’re cheaper), and crouching “people” (played by mannequins) on the shoulder, changing tires. There’s a wide freewayesque thoroughfare, where we max out at a very thrilling 45 miles per hour, and a twisting, ultra-narrow road with tight bends.

When testing begins, Uber employees swarm this mini city’s streets in buses, cars, road bikes, and dirt bikes (to properly train the autonomous cars to recognize “all types of motorcycles,” according to Thomason). The goal is to make sure that when an unpredictable cyclist swerves onto the road, the self-driving car hits the brakes.

The track is laced with fun house–style triggers that pop up along the way (including one of a jaywalking pedestrian), which help Uber assess the car’s onboard sensors and train vehicle operators to take over the car’s autonomy mode when its algorithms don’t react quickly enough. But the track feels more like Disneyland’s Autopia, a space with lots of room for error, and less like an actual, hectic city street with double-parked trucks, errant drivers, and lots of unpredictable pedestrians. It’s one thing to get it right on the test track — and it’s another to successfully manage the challenges of a real urban environment.

The future of driving is, well, not driving. It’s letting software take the wheel, and assuming that, if a kid comes running out onto the street, your driverless robot car will know to swerve or stop to save a life. Fully autonomous vehicles aren’t the norm yet, but semiautonomous cars with different levels of driving capabilities are already on the road.

The current generation of autonomous Ubers cars, codenamed Krypton, are frequently forced out of autonomy while they’re in operation for situations the cars aren’t yet equipped to handle, like driving over train tracks or unprotected left turns. The next generation of cars, Uber says, can drive without a human operator and have significantly more space in the trunk, where much of the vehicle’s computing hardware is stored. The company claims its high-tech cars have driven over a million miles and provided 50,000 rides, up from 30,000 rides in September 2017.

Meanwhile, Alphabet has announced that its Waymo cars will start giving people rides without a human in the driver’s seat (though there will be an operator somewhere in the car) in Phoenix, Arizona. Tesla’s Model S and Model X have a freeway-ready “autopilot mode.” And even consumer cars, like the Ford Escape, have had some autonomy built-in for years: the ability to parallel-park themselves.

Eric Meyhofer, who is currently leading the company’s self-driving efforts, points to Uber’s built-in network of paying passengers in need of a ride as its key advantage in the race to bring autonomous vehicles to market. “We have the machine running well enough that large quantities of miles are coming in every week from each city,” he says, “and that’s what gives the developers the data they need to test their software every week and get better and get more reliable.”

UberX customers who are paired with a self-driving Uber pay normal rates (surge pricing and all) and have a chance to request a human driver instead. Those who opt in will get to experience what it's like to be in an autonomous vehicle firsthand.

When I take a ride on the construction-clogged streets of Pittsburgh, the first thing I notice is that my car is hardly self-driving. Every few minutes, vehicle operator Jonathan Dailey grabs the wheel, and a chime indicates that the vehicle has transitioned out of autonomy. Dailey holds his hands in the eight and four o'clock positions, as if he's about to start steering, for the duration of the drive.

“We call it the ‘light-touch grip,’ where we touch [the wheel] but are not manipulating controls,” says Dailey. “I do keep [my hands] there just in case, because we have a lot of noncompliant drivers around that cut us off, or stuff like that.”

The car slows for a garbage truck ahead and, although there’s plenty of room to pass around it on the left, the Uber comes to a full stop and doesn’t budge. Dailey takes over the controls and navigates around the truck, while another operator in the front passenger seat, Jutaporn Huesman, flags the incident for review.

As we’re driving down Butler Street, a heavily trafficked, narrow two-way route through the city’s hip Lawrenceville neighborhood, a wide truck that’s parked in a loading zone juts into the road. The self-driving Uber successfully squeezes around the truck but, a few seconds later, about five feet past, hits the brake, hard. “There was a bit of latency there,” Dailey says.

By “latency,” he means the sensors detected an object in the lane and stopped — too late. “We’re running a newer software, so it’s not completely dialed in yet,” Dailey says, probably in reaction to the panic that suddenly flashed across my face. Self-driving Ubers have had a few issues since they launched, including one running a red light in San Francisco and another flipping on its side after a crash in Arizona (according to a police report, however, the Arizona crash was the result of a (human) driver hitting the Uber vehicle). Autonomous driving software has also been linked to a death. In Florida, a driver using Tesla’s autopilot mode was killed while speeding on a highway.

Aside from a few other hiccups — including coming to an unexpected halt on Liberty Avenue, a main road, because the software (wrongly) predicted a woman opening a car door was going to jump into the street — the ride is entirely uneventful and, mostly, v e r y s l o w. Uber’s self-driving cars, when in autonomous mode, follow the speed limit at all times, even if, for example, a 25-mph limit applies only when school is in session. So impatient Pittsburghers, eager to get by, are right on the heels of our speed limit–abiding Uber the whole time.

Matthew O’ Polka, a Pittsburgh resident from the Bloomfield area who says he lives on one of the main streets Uber uses for testing, tells me sharing the road with a self-driving Uber is “like driving behind a super-cautious driver.”

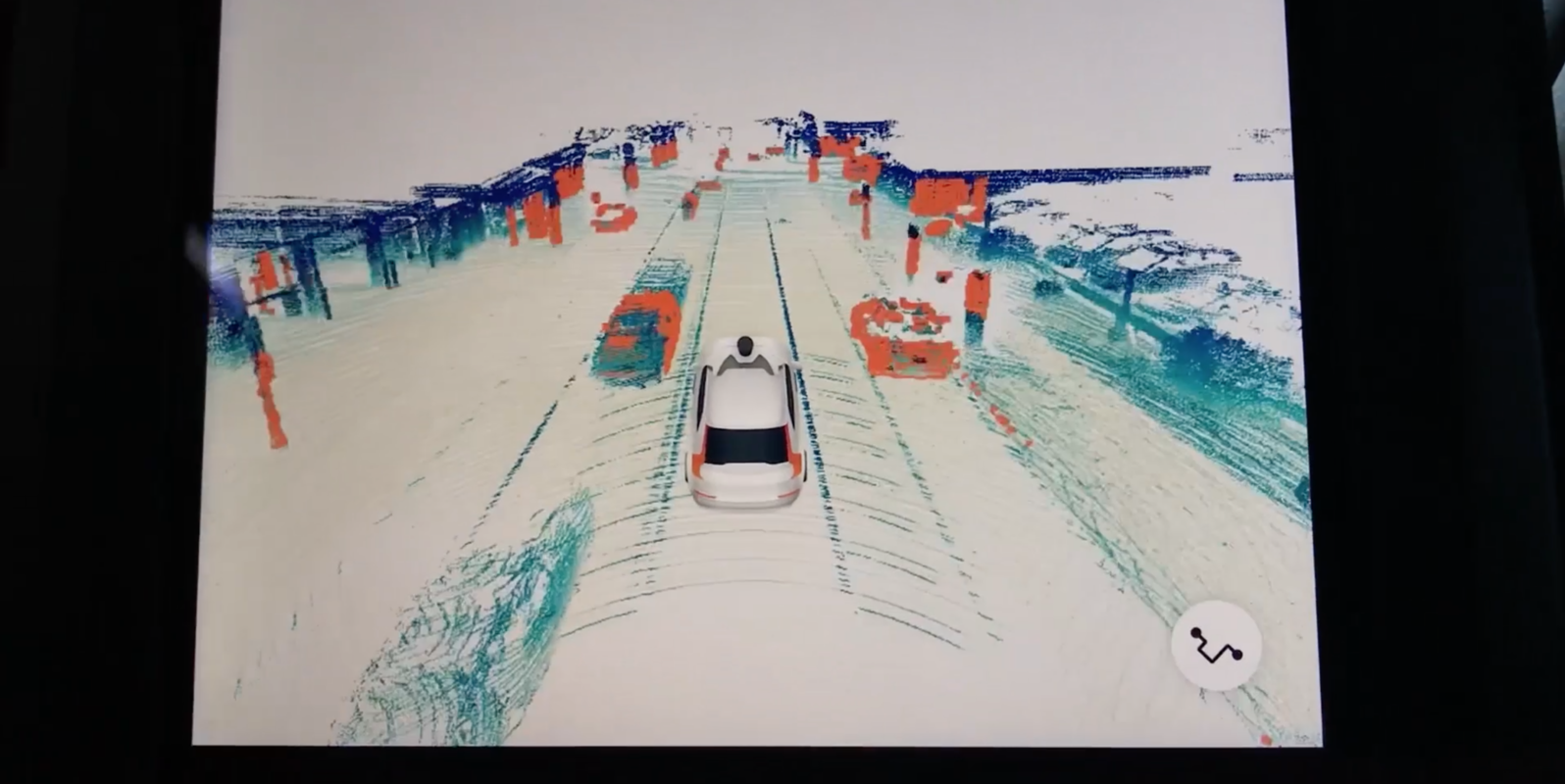

Self-driving Ubers only take very specific routes that have been mapped by an internal team at Uber. “Maps tell us lots of interesting stuff that we don’t have to compute on the fly,” says Thomason. “We can find [stoplights and stop signs], but it’s even better when we have those stored away. And that helps with scenarios like the sun being behind the stoplight, which happens in California.”

Having stored mapping information also means the car doesn’t need to rely on road lines to center itself in a lane. Instead of looking at, say, where the yellow stripe splitting a two-way road is, the car’s path is predetermined by mappers. “We kind of decide at a map level generally where the driving path should be,“ Thomason says.

That reliance on maps, though, can be problematic. At one point the Uber begins driving into the middle of a new bike lane that, according to our vehicle operator Dailey, hasn’t been mapped yet. Our trusty human overseer takes the car out of autonomy as soon as he realizes the car is veering into unwanted territory.

A resident I speak to, fourth-year University of Pittsburgh dental student Giana Lupinetti, says autonomous Ubers don’t drive the way humans in her city do. “I would say Pittsburgh drivers are a little bit more aggressive. People here tend not to abide by the rules. That’s why Ubers stand out a little bit.”

On one winding road, for example, the car takes exceptionally slow, cautious turns, because it can't see down side streets occluded behind the road’s bends.

It would be frustrating, I imagine, to be in a rush and also be stuck in an Uber that moves at a glacial pace.

Uber’s self-driving fleet operates like clockwork. The vehicles are deployed from centralized garages where the morning shift comes in at around 5:30 a.m. and starts picking up passengers at around 6 a.m.. Then around 3:15 p.m. in the afternoon, the cars are refueled, and cleaned back at base.

There, the cars are plugged in and begin uploading massive amounts of data — including hours of high-resolution video footage and radar recordings. A car’s camera captures *everything* that happens around it and that footage is reviewed meticulously.

Meanwhile, the next shift of self-driving Ubers prepares to hit the road.

It’s clear that Uber is making a huge investment in self-driving technology, and wants to get its cars on the road — fast.

“It’s a really hard problem. …. 20 people aren’t going to solve this. I mean, they would solve it in 50 years. You’re not going to have a small team do this. For us, time to market matters,” says Meyhofer, who was appointed head of Uber ATG recently after the former lead, Anthony Levandowski, was accused of stealing self-driving car technology from Google.

In 2015, Uber announced it was creating a strategic partnership with Carnegie Mellon University and that it was also creating Advanced Technologies Group. Shortly after, about 40 of CMU’s researchers, including Meyhofer, left to go in-house to Uber.

The team had 45 people in January 2015; nearly three years later, Uber ATG has over 1,500 employees. Of the department’s growth, Meyhofer comments that “it’s been like drinking from a fire hydrant for the last three years.”

Thomason aspires not just to bring more self-driving taxis on the road, but to be the “premier autonomous vehicle platform provider.”

“We have a network that is second to none today, as far as ride sharing goes,” he says. “And we are going to bring vehicles onto it, with our autonomous software. We’re going to bring third-party suppliers in, we have a great relationship with Daimler, we have this relationship with Volvo. We are planning to make a platform that companies can come in and bring their cars into.”

Moving from its current network of human drivers to autonomous vehicles would be hugely beneficial to Uber's bottom line. While both Meyhofer and Thomason say Uber will still rely on human drivers for the foreseeable future, labor is expensive, and a robot driver would eliminate the cut Uber has to pay its drivers to complete a ride, driving down costs and potentially increasing profit. And not having to rely on human drivers isn’t the only motivation for Uber to embrace self-driving tech. In 2014, the company’s founder and former CEO Travis Kalanick pointed to a future with less congestion, safer rides, and the economic benefits of not having to own a car — with autonomous Ubers at the center of it all.

The company and its drivers have had a contentious relationship over the years. Uber touts its platform as one that “boosts the incomes of millions of American families,” while in reality, many drivers earn little money — in some cities, they barely make minimum wage after expenses. Uber is currently fighting a class action lawsuit from drivers who say they should be classified as employees, not independent contractors, and are entitled to gas and vehicle reimbursements.

Thomason says the company’s interest in self-driving is about expanding its reach: “Uber is providing lots of capabilities for people to provide for themselves, and get rides when they need it, but we really need to have the flexibility to send cars right where we need it, when we need it. And [self-driving vehicles] will give us that.”

Senior Product Manager Emily Duff-Bartel also points to the cars’ safety: “There’s tons of statistics around freeing up city space for parking, turning it into green spaces … but the big thing is the 1.5 million lives that are lost every year to traffic fatalities, that this technology can really start to make an impact on and improve.”

There are other benefits, too. Robots, for example, can’t discriminate in the same way that human drivers can:

I just had an @Uber driver stop, look at me, say “no”, and drive off. Without me in the car. And uber charged me $5 for that.

But the company’s efforts could hinge on its upcoming trial with rival Waymo, which is seeking $1.9 billion in damages. It’s unclear what will become of ATG should Uber lose the case.

What is clear, however, is the inevitability of autonomous vehicles. In addition to Alphabet’s Waymo, companies like the Ford-backed Argo AI, the GM-owned Cruise Automation, Apple, Audi, Intel’s Mobileye with BMW, MIT’s nuTonomy, and Tesla, with its new self-driving trucks, are all working on eliminating humans in the driver’s seat — and many, including the Department of Transportation, cite the 2020s as when we should expect them all over our roads.

But not so fast, says MIT professor Jonathan How. “It’s going to take a long time… There’s going to be an expectation where you see cars at more autonomous levels than Tesla, for example, in that time frame, but they will only start to appear in limited deployments.”

Steven Shladover, of University of California Berkeley’s PATH (Partners for Advanced Transportation Technology) program, agrees: “One might be able to drive in an autonomous vehicle in a very limited set of conditions ... but to get to a vehicle that can get everywhere, that people can ride is all sorts of weather conditions, is not something that’ll happen in my lifetime," he says. "And I don’t think it’ll happen in your lifetime, either.”

Self-driving cars may not take over our roads by 2020, or even close to that, but they will become more and more prevalent in, How believes, “limited deployments,” like in certain cities, campuses, and airports. And while the world’s biggest tech and automotive companies run real-world tests to make autonomous driving a reality, these robot cars are going to drive slowly, cautiously — and make us a little carsick — until they can learn to drive like humans. ●