When you die, you won’t just leave behind your 401k, your belongings, and your life insurance. You’ll leave your Facebook photos, the embarrassing emails you wouldn't want anyone but your best friend to read, and the meme tweets you might not want to survive you, too.

Whether or not you want to control what happens to your digital afterlife is up to you, but if you don’t make any plans, it might make it harder on friends and family to wrap up ties when you’re gone. So set aside some time to prepare for the worst case scenario — it’s much easier than you might think.

Start with a will, the most important preparation you can do. You can write one for free online, and it can take as little as 15 minutes.

“For a single person, it’s going to take them 15 to 20 minutes to prepare their simple will,” said Brent Pope, founder of DoYourOwnWill.com and a former military lawyer. Pope’s website starts with a quick questionnaire and then automatically compiles a document that can be downloaded as a PDF. LegalZoom and RocketLawyer offer similar services, but require paid membership (although each service offers a limited 30-day and week long free membership trial, respectively).

You’ll name someone to take care of your “estate” (or, everything you own, including stock, money in your bank account, and belongings). That person’s called an executor* and, according to Pope, you should pick someone you trust to handle a serious matter and “can be as non-emotional about the process as possible.” They’ll file all sorts of important paperwork and need to keep a level head. If you store important documents or info on a hard drive or other location, you’ll want to note that in your letter of instruction to your executor.

Then, you’ll decide where the things in your estate will go and who gets them. If you have kids, you’ll name a guardian* for your children. Easy.

*You should, of course, talk to your named executor or guardian to make sure they’re comfortable with the role. If you die and they refuse the role, your estate will be passed on to the state.

But you can’t just print out a form on a website: You have to sign the will.

“People save it on their desktop or print out their wills and don’t sign them. It needs to be a wet pen to a piece of paper. If you take the time to write it, take the time to sign it,” Pope advised. When you sign it, you’ll also need the dates and signatures of two witnesses who are at least 18 years old and won't receive any benefits from the will. Every state is different, but in many places wills do *not* actually need to be notarized — that’s the process to certify that the person signing the document is actually you, by showing some form of identification or comparing fingerprints.

Additionally, be sure to check on each of the assets named — some can be affected outside of your will. Say, for example, you'd designated someone (also called a “beneficiary”) to inherit your 401k or life insurance policy, which is something you can do when you sign up for either. If you decide to leave everything in your will to someone else (perhaps because you wrote a will after the fact and forgot you had already chosen a beneficiary), the 401k or life insurance policy won’t respect your will. It’ll pass the assets to the beneficiary, no matter if it’s a crazy ex-spouse or someone else equally undesirable.

Keep in mind, you’ll need to revisit and update your will after big life events: when you get married, have kids, get divorced, or get a big job promotion and increase your income levels in a serious way.

OK — now your will’s out of the way. Move on to the second most important thing: the passwords to your accounts.

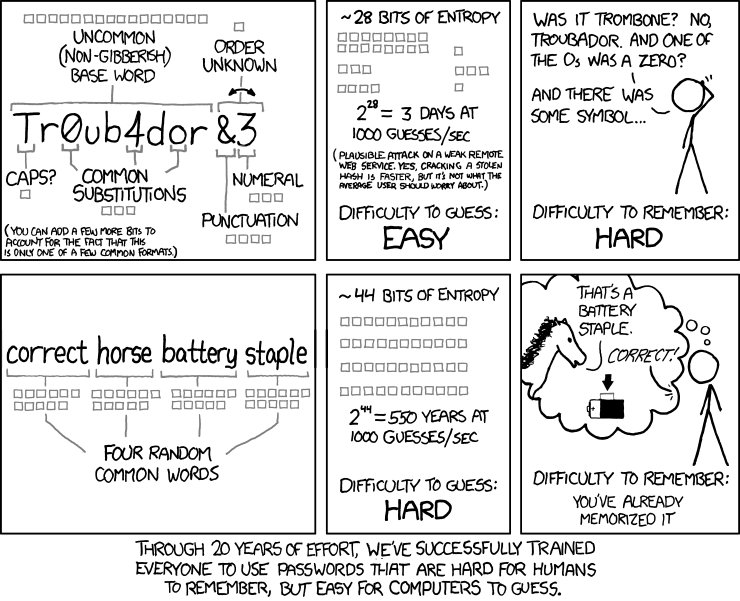

This is where it gets a little tricky. Security features like two-factor authentication and software like password managers protect your accounts while you’re alive, but they make it incredibly difficult for your trustees to gain access to accounts.

Password managers** are GREAT and everyone should use them. They help you create long, randomized passwords that are hard to guess and then encrypt the passwords, making it incredibly difficult for hackers to break the code. Most managers just require you to remember one password: your master password (which should be equally long and random). But you can use your manager’s “Emergency Access” feature (both LastPass and Dashlane offer it) to give a trusted person access to your account without knowing your master password. You decide how much time should pass before they’re given access, so you can decline access if needed.

So that solves the problem of your passwords, but what about two-factor authentication?

If you use SMS to receive codes that allow you to sign in to your online accounts, it may be incredibly difficult for your executor or trustee to get them. There are two ways to get around this:

- Instead of using SMS, you can get a security key, which is a physical gadget that can be plugged into a computer’s USB port and acts as a second factor authenticator for Google, Facebook, Dropbox accounts, and many more. Keep that key wherever your will is stored.

- For accounts that don’t allow security keys, create backup codes if you can, and print them out or store them in your password manager. Because you’ll need to use these codes occasionally yourself, make sure you generate a new set of codes every year and update wherever you’re storing them.

**LastPass and Dashlane are fantastic free options with premium upgrades. 1Password, which only offers a paid version, is a better option for families ($60/year for 5 people).

Google has its own way of managing its users’ deaths. It’s called the Inactive Account Manager.

It's pretty self explanatory: You can set a “timeout period” after which Google will treat your account as inactive. Once it’s deemed inactive, you’ll get a text or email — and Google will notify trusted contacts whom you’ve designated. You can decide whether or not the account should self-destruct and even set an auto-response in Gmail. You can also elect to automatically share all or some of your Google data — photos, documents, emails — with someone after the timeout period.

Facebook also has a plan for sudden passings.

Friends and family can report the death to Facebook with a memorialization request (proof of death is optional, but the company does require a date of death). The profile will then say “Remembering” So And So, but no one will be able to take over your account if you haven’t set what’s called a “Legacy Contact.”

After the profile is memorialized, you won’t show up in places like birthday reminders, People You Know, or ads.

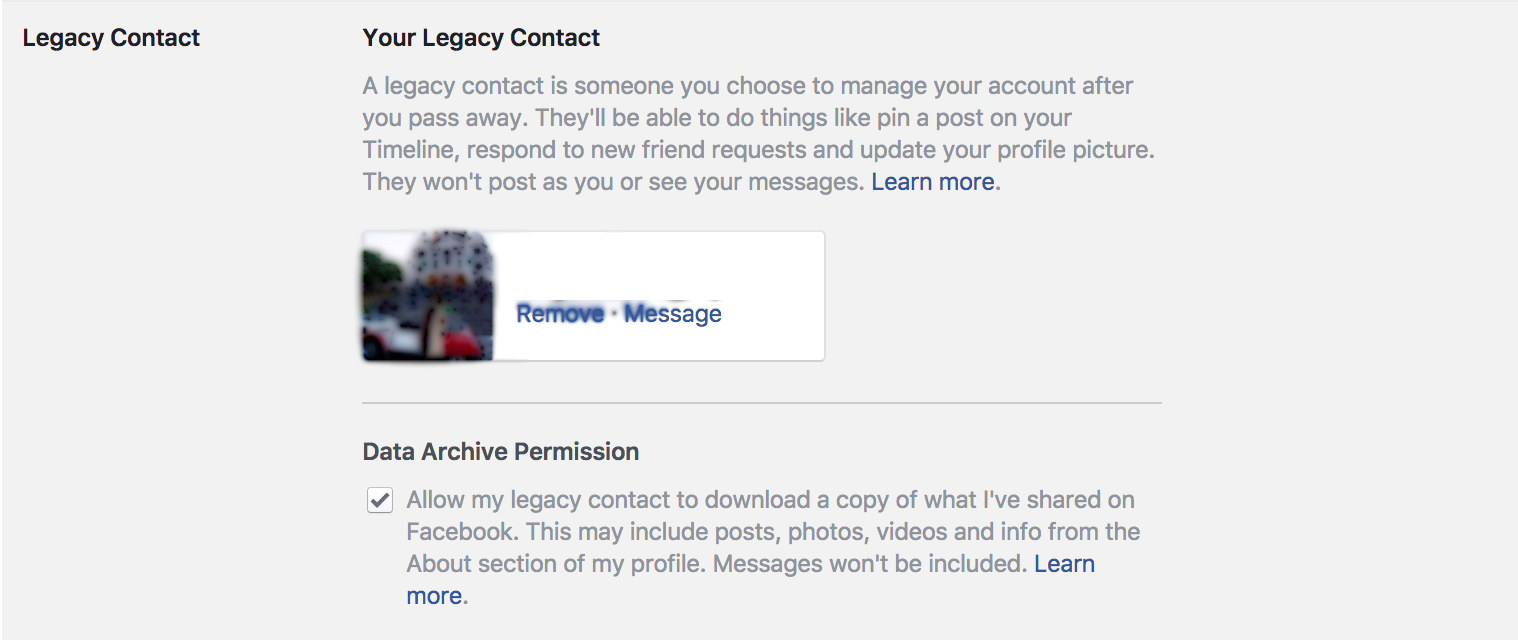

Choose someone to take over your Facebook account when you die, or delete the account entirely.

This anointed person is a “Legacy Contact.” You can only choose one (so choose wisely) and only someone who currently has a Facebook account (no social media resistors allowed). They’ll have power over your public digital legacy (hence the name): the ability to change your profile picture and cover photo, write a post on the timeline, and respond to new friend requests.

Plus, they can look at all of the photos/videos you’ve uploaded, wall posts, events you’ve attended, and friends/randos you’ve friended over the years. What they can’t see are your DMs. Family members with court orders, however, can request additional information from Facebook, but it’s not guaranteed that the company will grant it.

Access this setting by going to facebook.com/settings, clicking on the Security tab, and then going to where it says Legacy Contact. Here, you can also set up an annual reminder to review your legacy contact or request account deletion.

If you don’t set a trusted contact or elect to destroy your account, all of your shared content will remain on Facebook with no one to manage it.

For other social media accounts, it’s not as straightforward.

On Instagram, someone will need to report the death with proof, like a link to an obituary, news article, or death certificate. A memorialization freezes the account: Photos or videos already shared will remain visible, and nothing can be added or changed, though users can weirdly continue to send direct messages to the deceased. Immediate family members can also request a removal of an account from Instagram.

Twitter’s policy is similar to Instagram’s, and so is LinkedIn’s. The service will deactivate or remove an an account, but only if an immediate family member is requesting.

On Snapchat, there is zero guidance on what happens to your account when you die. You can give someone your Snapchat username and password, and instruct them to delete your account when you pass — but that’s putting a lot of trust in someone.

When all of this is done, you — and your trusted friends and family — will be in great shape.

It’s pretty grim, thinking about death. That’s why so many people avoid The Will, the paper that’s a physical reminder that you will one day perish. But if you don’t prepare for the inevitable, your loved ones will face a mountain of complicated paperwork and logistics right as they’re coping with your loss.

If you have plane tickets, for example, they’ll need to cancel them and try to get them refunded. Or if you have credit cards, they’ll need to freeze those accounts. They’ll need to file taxes on your behalf, too. Grieving, as it turns out, is a lot of work for those closest to you.

Pope of DoYourOwnWill put it this way: “Think of yourself as doing a favor for those you’re leaving behind.” So, take a deep breath, spend a day or two putting a plan in motion for the unthinkable, and go ENJOY your life without having to worry about what happens after it.

This week, we're talking about preparing for and surviving the worst things imaginable. See more Disaster Week content here.