The blazing Karachi sun shines down upon me as I race across a chalk-covered playground to my mother, who’s waiting under a green tent. As I approach to hug her, my mother deftly side-steps, revealing a middle-aged woman donning a simple, cotton peach salwar kameez.

“Neha, this is Asiya Baji. She’ll be helping me take care of you…and she’ll also be playing with you when I’m not at home! How exciting is that?” my mother says in an upbeat tone.

I frown, unconvinced by what is playing out in front of me.

My mother continues optimistically, “I brought Asiya to see the Convent. This way she’ll know the pick-up routine…Neha, say Salaam now”.

Before I reluctantly mumble something kind, Asiya booms forward jovially, a seemingly relaxed smile plastered across her face.

“Salaam-u-Alaikum! Kesi ho meri beti?” (Urdu for, “How are you, my child?”)

The situation seemed bizarre – why was a 9-year-old suddenly being compelled to befriend a 50-something woman? Were my friend-making abilities that doubtful?

During the car-ride on our way home, I edge closer to my mother, remaining largely sceptical about the ebullient lady in her peach salwar kameez who just couldn’t seem to stop smiling.

The practice of hiring domestic workers is standard across countries like Pakistan and India. These workers are principally women, who leave their small, makeshift jhonprees (huts), situated far from the city, and travel long hours in over-packed buses and rickshaws to turn up for work at our lofty homes. Some women are hired as cleaners, some as cooks, and some as both. Quite a few are also hired to take care of young children. Though these women work chiefly in the hopes of scrapping up cash to provide a decent living for their family back home, they can often become so much more than the roles they are assigned.

Initially, I remained distant and sceptical of Asiya. When she’d arrive at my private school and wholeheartedly welcome me, I didn’t reciprocate fully as I tried my level best not to draw attention to this unlikely friendship. As I largely ignored her within the premises of my private school grounds, the guilt would eat away at me internally until I eventually compensated for my shallow behaviour.

It started out gradually. Once the two of us were far enough from school grounds, I’d purchase two newspaper bags filled with lemon-drizzled, spicy makai (corn) from a roadside vendor. During our car ride home, we’d silently munch on the makai, staring out our windows at the bustling Karachi life.

Indiscriminately over lunch one day, my mother casually informs me, “Neha, I think you should teach Asiya some remedial English or Mathematics. Or both”. She told me that Asiya hadn’t been allowed to continue her studies beyond fifth grade.

Perhaps it was the budding feminist within me, desperate to grant back the education which was cut short for Asiya, or the uncomfortable feeling of privilege, but I handed Asiya my old school notebooks, hung a small whiteboard against the knobs of my window, and put out a chair opposite my desk.

The tutoring sessions, which were sporadic at best, provided something more than basic education – they provided a gateway into deeper conversations. During the end of each session, the lulls of awkward silences often gave way to personal reflections. All this while, I wasn’t sure who benefited more from these lessons — Asiya or me.

After an unusually long afternoon session, I got up to wipe the slate of the whiteboard clean, when Asiya quietly divulged a detail of her past, “Did you know Neha? When I was exactly your age, I was set to be married to my first cousin”.

The concern on my face must have been evident, because she quickly continued, telling me that it had been a happy marriage with four beautiful children — two boys and two girls. She told me about her devoted husband and how he would do his best to sustain their livelihood in Haripur (a small district in Pakistan’s North-West Province).

I nodded wordlessly, uncertain about what had brought on this unwarranted reflection. Nonetheless, I took the opportunity to confirm a rumour I had heard floating about in my parents’ conversation, “How did he, um, sorry, your husband, Laal Khan…die?”

She gave out a short laugh, puffing air out of her nose, “So you know! Hmm. Beta, twenty years ago, there was a dispute in our village over some land, which sadly led to a brawl. My husband, the angry man that he was, stupidly got involved. He was murdered. I was in my thirties or forties, I guess”.

Baffled, I probed, “Did you do anything!?”

“I did, beta”, Asiya continued, almost completely sad now. “I took legal proceedings against the murderer, but it all went in vain when it began taking a financial toll on my family”. She then told me about how her heart closed off after that and how, overnight, she became the sole breadwinner of her family. She didn’t really have the time to be upset. I was taken aback by Asiya’s profound rawness about her own life – the immense vulnerability and resilience which lay within her. The conversation managed to thaw almost all the ice between us.

The formality of the teaching sessions was now replaced with sincere conversations about unspoken dreams and untrodden past paths. Although a lot of what was said was lost in translation, across Urdu and English syllables, it was as if Asiya and I both understood and truly believed in what the other was saying. Soon, she was slowly woven into the fabric of my teenage life.

We grew particularly close to each other when, during my older sister’s childbirth, my mother left me in the custody of Asiya (and my middle sister) as she headed for the States. With my mother now gone, I spent every waking moment of that winter with Asiya; chatting over breakfast, half-awake, pensively working on school work as Asiya laid on my bed pondering about her children in her village (something she often did) or coercing her to overcome her modesty, and dance expressively to Bollywood music. Asiya was the consistency I craved in my life – she steadied me, whilst I kept her away from the tremendous loneliness which she often felt living so far from home, just so that she could look after me.

As I headed into my late teens, there was now a burgeoning pressure to make the correct “adult decisions”. I was crumbling under the expectations of my father who reiterated, almost on a daily basis, that he wanted an “Ivy League school and nothing less”. Therefore, during my high school years, I remained primarily confined within the four walls of my room which were now filled with highlighted sticky notes, SAT preparation books, and medical school aptitude tests. Around this time, I had also soundlessly and quite suddenly become resigned. Internally, I was dealing with the anguish and trauma from two mental health conditions, which I’d only come to acknowledge during my time in university.

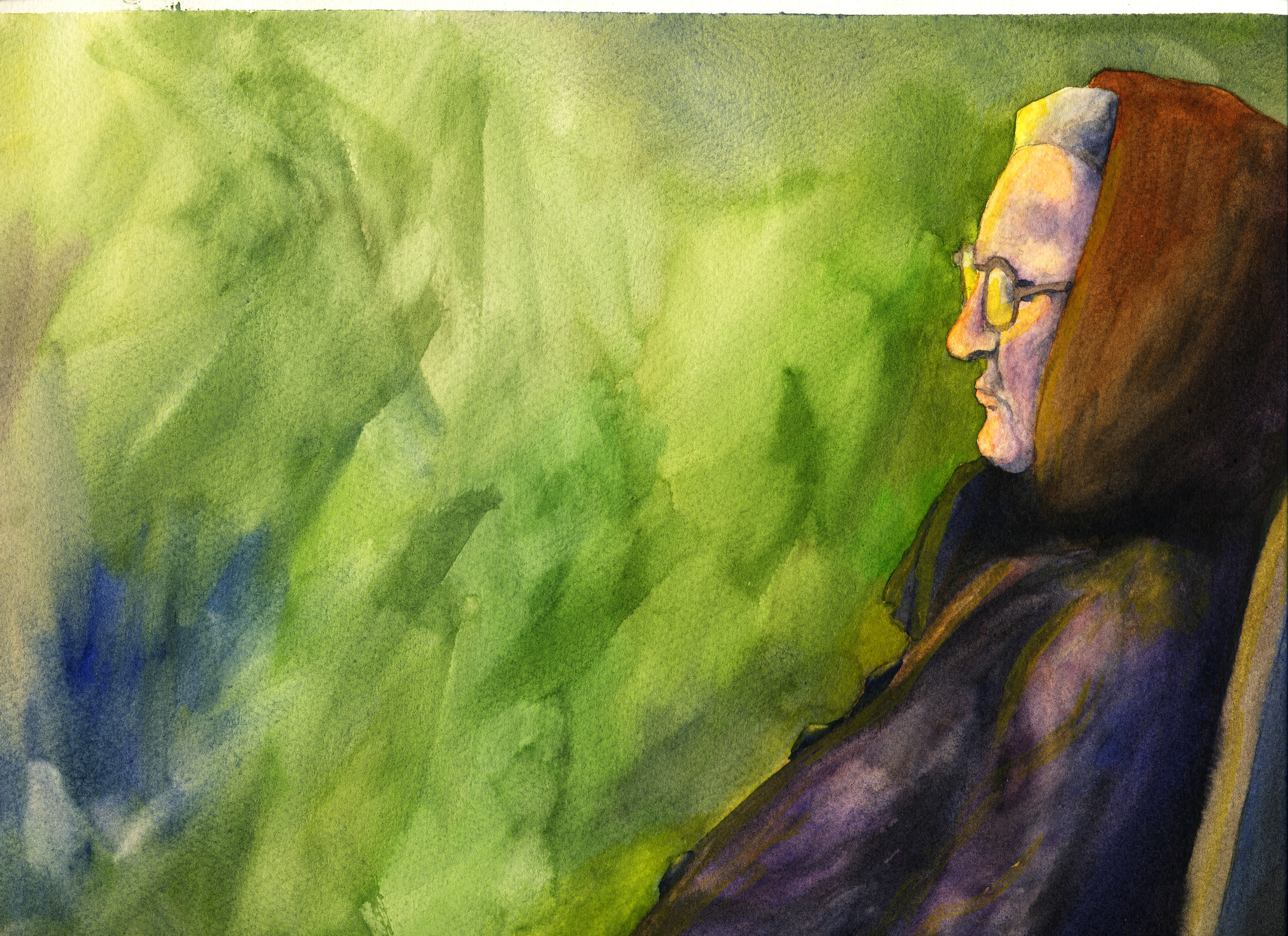

For four years, I remained so caught up in chasing dreams, that I didn’t realise that as I was growing older, Asiya was growing elderly. I had justified my choice to become reclusive by placing my studies on a pedestal, believing that they took precedence over spending time with Asiya. It seemed that Asiya had silently come to acknowledge this because she didn’t approach me as much anymore. Despite the remoteness from my older self, Asiya had seemingly come to terms with my changed demeanour, yet never completely abandoned me.

Come July, I was now eighteen and leaving home for the first time to head to university in the UK. The night of my flight, Asiya and I quietly stood by the main door in a tight embrace, until we were both shaking as we began to weep uncontrollably.

My three years in college seemed longer than they needed to be. During the day, I would occupy myself with the company of friends and club activities. But each night, when I returned to my small dorm room, I was immediately struck with the thought of Asiya.

I would speak to her periodically whenever I’d call my parents back home, who’d graciously pass on the phone to her. Over one phone call, she revealed that she had been unable to go near my room in the initial months of my departure for college. I grew remorseful over my treatment of Asiya — she was my friend, and I knew how lonely she had felt in Karachi, and yet I had left her alone, in that small room with just the pressing glare of the T.V.

Following my graduation, I returned home to Pakistan. hoping to reunite with Asiya and make up for lost time. But she was now a changed person — she was slower in her movement, more forgetful, easily irritated, and longed to return to her village more than usual. During that time, the COVID-19 pandemic had wreaked havoc across the globe and unfortunately, Asiya managed to contract the virus upon her visit to her brother over Eid. Her recovery was slow as she endured tremendous weight loss and physical weakness. Upon the consistent urging of her children, she decided to finally return to her village in Haripur. When she came back to our house to pick up her belongings, I was only allowed to wave goodbye to her from a distance.

It has been more than four months since she’s been gone, and I don’t know when I’ll be seeing her next. Asiya is currently back in her village, where she's spending time reconnecting with her children and her grandchildren while also paying visits to relatives and friends within the community. I've never been exposed to or know truly well the life that exists for her beyond the four walls of my house. I've only ever known Asiya one way. Only from her descriptions can I imagine what her home must look like, and the greenery which exists around it, or the language that is spoken, and the traditions, customs, and beliefs which exist within her family.

Asiya was never a “maid” or a “nanny”. She was never someone who was simply there to help us around the house with laundry, or cleaning, or cooking. She was the most unexpected friend who had a profound impact on the life I led and the decisions I now make.

She was someone who taught me that love cuts across classes and strata; that it comes in the most unexpected ways — enjoining us over the commonalities of life — the need to love, to be loved, to connect, to protect, and to progress. She was the woman who, in many ways, raised me. And no, she was not my mother. I was lucky to have a mother and an Asiya in my life.

Despite people like Asiya forming a large proportion of the informal work sector, they are never acknowledged more holistically within popular culture. Within films or literary mediums, they are never seen as companions, confidantes, or even parental figures. South Asian films particularly play into the tropes of female domestic workers who hail from homes where they are the primary breadwinners and wives to alcoholic or abusive partners. Whilst this is true in some cases, the stories of these women are grander than these stereotypes.

In the 2018 film anthology, Lust Stories, one of the episodes directed by Zoya Akhtar depicts the story of a maid, Sudha (played by Bhumi Pednekar), involved in a sexual relationship with her employee, Ajit (Neil Bhoopalam). Outside of this relationship, Ajit largely ignores Sudha and eventually becomes engaged to another woman from a similar social class, as a distraught Sudha looks on and says nothing. This is a story perhaps told many times before, which once more perpetuates the notion of female domestic workers as nothing more than silent sufferers at their employer’s hand.

Male domestic workers are not free from being caricatured and Piku (2015) delineates that well. Bhudan (played by Balendra Singh) is a male domestic worker living with a 30-something Piku (Deepika Padukone) and her agitated father, Bhaskor (Amitabh Bachan). Whilst a certain intimacy exists between Bhudan and his employers — right from him being privy to every family matter to knowing intricate details about Bhaskor’s bowel movements, this intimacy shouldn’t be confused for closeness. Instead, Bhudan is merely a character that is meant to drive the plot further. He is there to perform ridiculous tasks for his equally ridiculous employers – like accompanying Bhaskor to the bathroom with his custom-made chair. Another scene which exemplifies the prominent divide between the worker and his employer is when Rana (played by the late Irrfan Khan), refuses to begin the road trip with Bhudan sitting in the passenger seat.

Domestic workers are people who live lives as rich and complex as ours and as such their depiction within popular culture should be considered more universally and given a meaningful backstory. Only then will this otherisation, this “us and them” mentality finally be put to rest.

Recently, I managed to catch up with Asiya over a phone call.

“Kesi ho meri beti?” Asiya softly asks.

“I’m fine! How are you? I miss you.”

I could feel Asiya smile.

After a few seconds of silence, I continue, “Asiya, I still see you”.

“What do you mean, beti?”

“I…I see you everywhere, in the most ordinary of places – on my bed laughing, in the kitchen cooking, on the stairs oiling my hair, on the charpai (bed) — sitting silently with your legs folded under you. This house is touched with memories of you, and glows in places where you lived and breathed”.

I could only hear a person sniffle on the other end.