My debut novel was published this summer at a moment filled with profound grief about the vulnerability of black women's lives. This year has been marked by the distant but still painful deaths of black women I don't know — Cynthia G. Hurd and others killed in cold blood in Charleston, South Carolina, and Sandra Bland, found dead in a jail cell in Texas. As I've tried to make sense of these events, the only thing that I've been able to hold on to is God.

When I was a child, I didn't understand why my grandmothers — Oriel from Barbados, Ruth from Antigua, and Lily from Jamaica — were so prayerful. Today, I understand the concept of getting prayed up, the reason why black women need anchors in a world that sometimes seems indifferent to our survival and at other times, dead set on our demise. Now, face to face with the brutal deaths of women like me and the women in my family, I look to God because there is no other place where I have been able to find peace.

I knew that my book's journey would be different than I expected when, just before its publication, my novel was mentioned in two takedowns of the unbearable whiteness of the New York Times summer reading list. At first I wondered, naively, why my writing was caught in the crossfire of these debates. And then I remembered the inescapability of my blackness, the way that race would propel me and my work into the world in ways that I couldn't anticipate and would have to engage. While I believe that writers have no social or political obligations beyond those they choose, I know that what will be asked of me will be different than what's asked of my peers. I write now in the tradition of writers who have lent their voices to social justice movements, including Edwidge Danticat, Junot Díaz, Roxane Gay, Binyavanga Wainaina, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, James Baldwin, and Audre Lorde. I am inspired by the youth-led movement in defense of humanity and against police brutality, embodied in the Black Lives Matter and #SayHerName campaigns.

The Sunday after the massacre in Charleston, I went to a church, the progressive Middle Collegiate, led by a black woman pastor, Reverend Jacqueline Lewis. I had been looking for a church home for some time. When I first visited I knew that this was where I needed to be — in a multiracial congregation that included artists, transgender folks, intergenerational families, and an out gay minister. That Sunday, the service broke my heart, already in pieces after digesting as much of the news as I could handle. Nine chairs were set out on the altar to represent the nine people who were killed in Charleston. And then the Sunday school children were asked to sit in these chairs in remembrance of the slain. I held my breath as I watched the children take their seats. The church fell silent; perhaps everyone was wondering, like me, if this gesture was too heavy for children. But then I remembered that, as Ta-Nehisi Coates writes in his book Between the World and Me, being a black child in America means confronting the fragility of your life at a young age.

The #SayHerName campaign asks us to call the names of the women who have lost their lives to racism and state violence. Among the dead is Cynthia G. Hurd, the librarian killed while attending bible study at Mother Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston. I see in Mrs. Hurd the kind of librarian who meant so much to me as a young reader and an aspiring writer; I deeply regret that I'll never get to meet her. I am haunted by the picture of 30-year-old Shereese Francis that circulated after her death at the hands of New York City police officers in 2012. I see myself in Francis's face — her chubby cheeks, her carefully applied makeup, her short and well-tended hair, and her modest dress, the inheritance of a daughter of conservative Jamaican parents. Each time I look at Shereese Francis's picture, I am reminded of the unfairness that she is dead and that I am still alive. When I think about my parents' sweet gesture of purchasing flowers at their Brooklyn church to celebrate the acquisition of my novel, I am reminded that the only flowers Francis's parents will ever buy for their daughter will be in her memory.

I was on book tour recently when the news of Sandra Bland's untimely death popped up in my Twitter feed. I read the story and started crying, holding it together just long enough to share the news report with my partner at the wheel. My heart sank as I read about how Sandra Bland, just 28 years old, was found dead in a jail cell in Texas, self-asphyxiation listed as the cause of death. Her family refused this explanation for Bland's death, confident that their child did not take her own life. She had everything to live for. She was young, gifted, and black. She had been a vocal activist in the Black Lives Matter movement that has mobilized young people in America and around the world. Reading Sandra Bland's story, and seeing her beautiful face, I am outraged by the injustice of her death. Each time I make a stop on my tour, I am reminded that Sandra Bland never made it to her first day at work, and that she will never travel again.

I want our dead to live, to write their own stories, to laugh and travel and love and fight. I want to live for just a moment in a country where my life and the lives of my sisters and brothers — straight and gay, transgender and cisgender, black and brown — are not imperiled at every moment, even in the homes we make for ourselves as a refuge. This summer has taught me both the limits and the necessity of my faith in these dark times.

I know that writing, like prayer, helps to close the distance between ourselves and our freedom. I love Lucille Clifton's poem "won't you celebrate with me" where she invites readers to "come celebrate / with me that everyday / something has tried to kill me / and has failed." Even as I celebrate the gift of my life, I do so knowing that I could just as easily be Sandra Bland or Shereese Francis or Cynthia G. Hurd.

There's God, and then there's the work that people of faith and fight are called to do. I am reminded of Assata Shakur, whose words activists turn to for strength. I've said Shakur's words with people of faith and fight in New York and New Mexico this year, and I leave them here now. "It is our duty to fight for our freedom. It is our duty to win. We must love each other and support each other. We have nothing to lose but our chains."

***

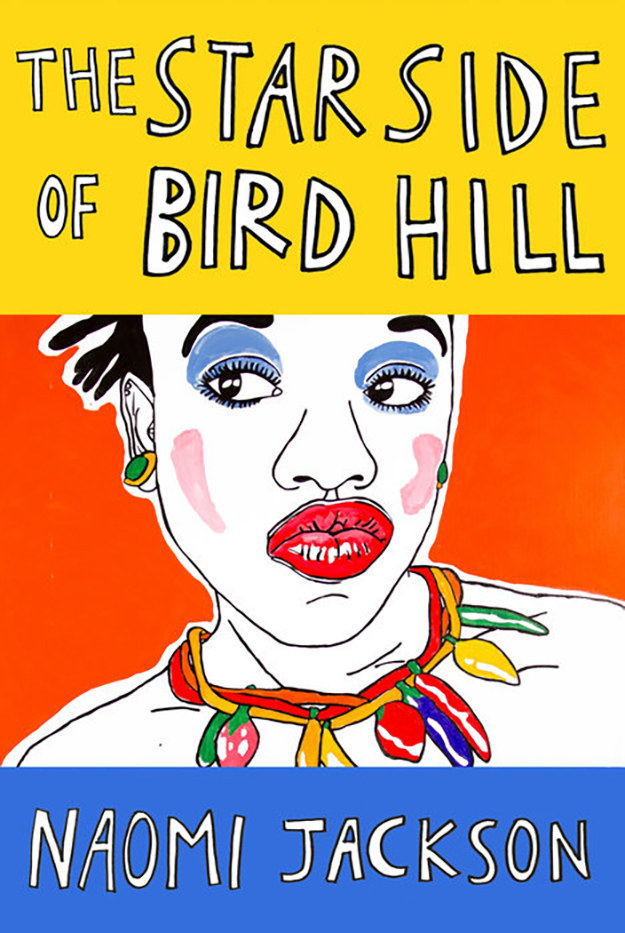

Naomi Jackson is author of The Star Side of Bird Hill, published by Penguin Press in June 2015. She graduated from the Iowa Writers' Workshop and lives in Brooklyn.

To learn more about The Star Side of Bird Hill, click here.