JOS, Nigeria — Bolu and his parents sat frozen in the car. Sweat was pouring down Bolu’s back, and he knew it wasn’t just the effects of suddenly coming off the tramadol and the codeine and the booze and the Rohypnol, and all the other drugs, all at once. He was on edge at the thought of entering the building looming in front of them.

Bolu’s last hope of getting clean after three years of dealing with addiction lay inside — a government-run rehab center in the central Nigerian state of Jos that was also home to drug runners and violent gang members, and terrifyingly alien to his comfortable middle-class upbringing. Run by the NDLEA, Nigeria's equivalent to the Drug Enforcement Agency, it was part rehab and part correctional facility, somewhere between a halfway house and a last-ditch hope.

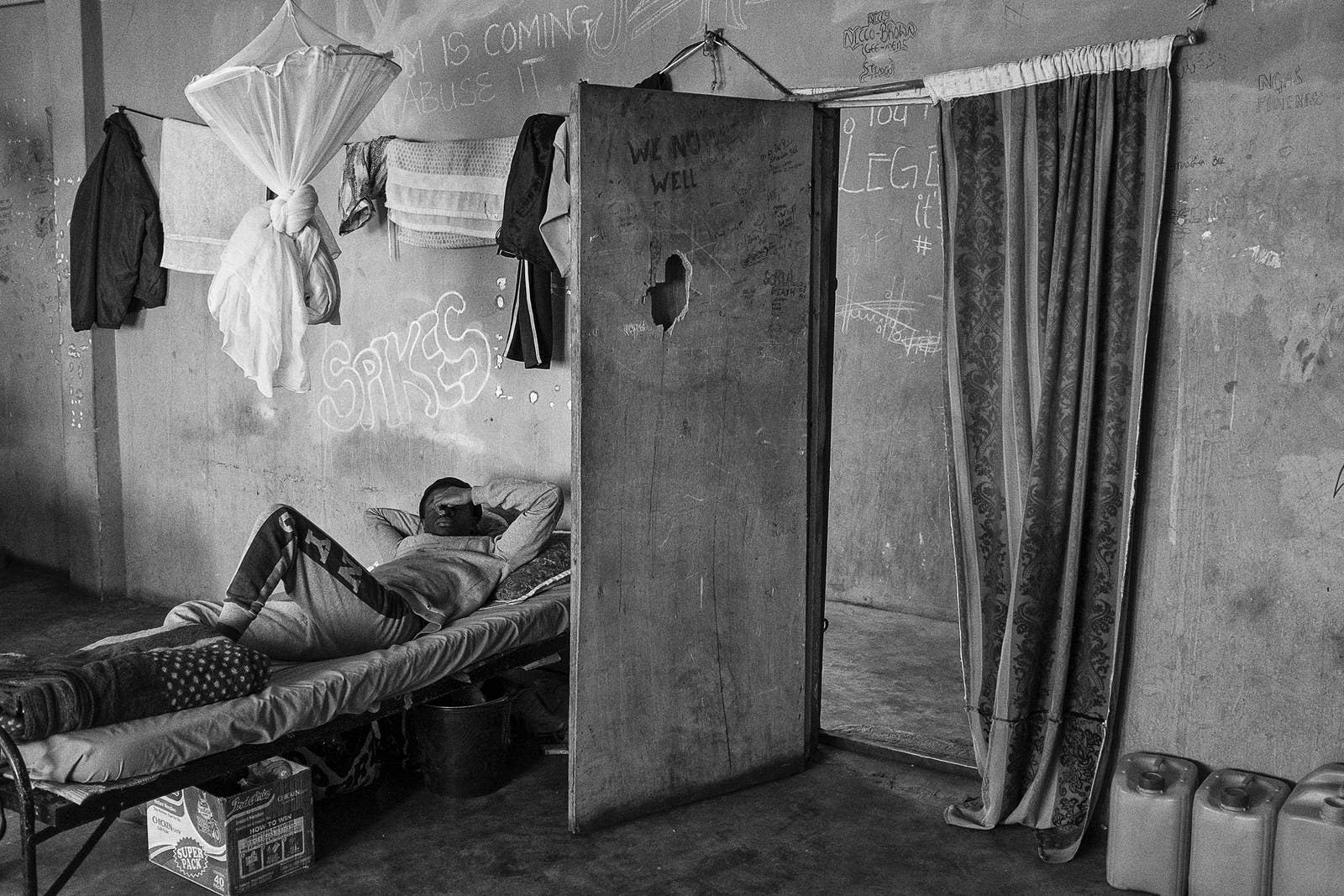

If Bolu walked in, the building’s peeling yellow walls would be his home — and jail — for the next four months while he embarked on a cold-turkey detox program to treat his addiction to tramadol, a legal but highly addictive painkiller.

In his father’s eyes, Bolu read the same thought that was racing through his own mind: Do I really have to go in there? The thought made him even more nervous, even sweatier.

Suddenly it didn’t matter that the day before, Bolu had hit rock bottom, making a panicked call to his father that triggered a 1,200-mile trip to bring him back from his college dorm. Or that, for years before, he’d fallen out with his family, flunked out of college classes, overdosed, lied repeatedly about being clean, overdosed again, and cut ties with almost everyone he knew before washing up here.

All that mattered now, he told himself, was that maybe he wasn’t actually an addict, like everyone else in there. Maybe he hadn’t really tried his hardest. This time he could quit for good.

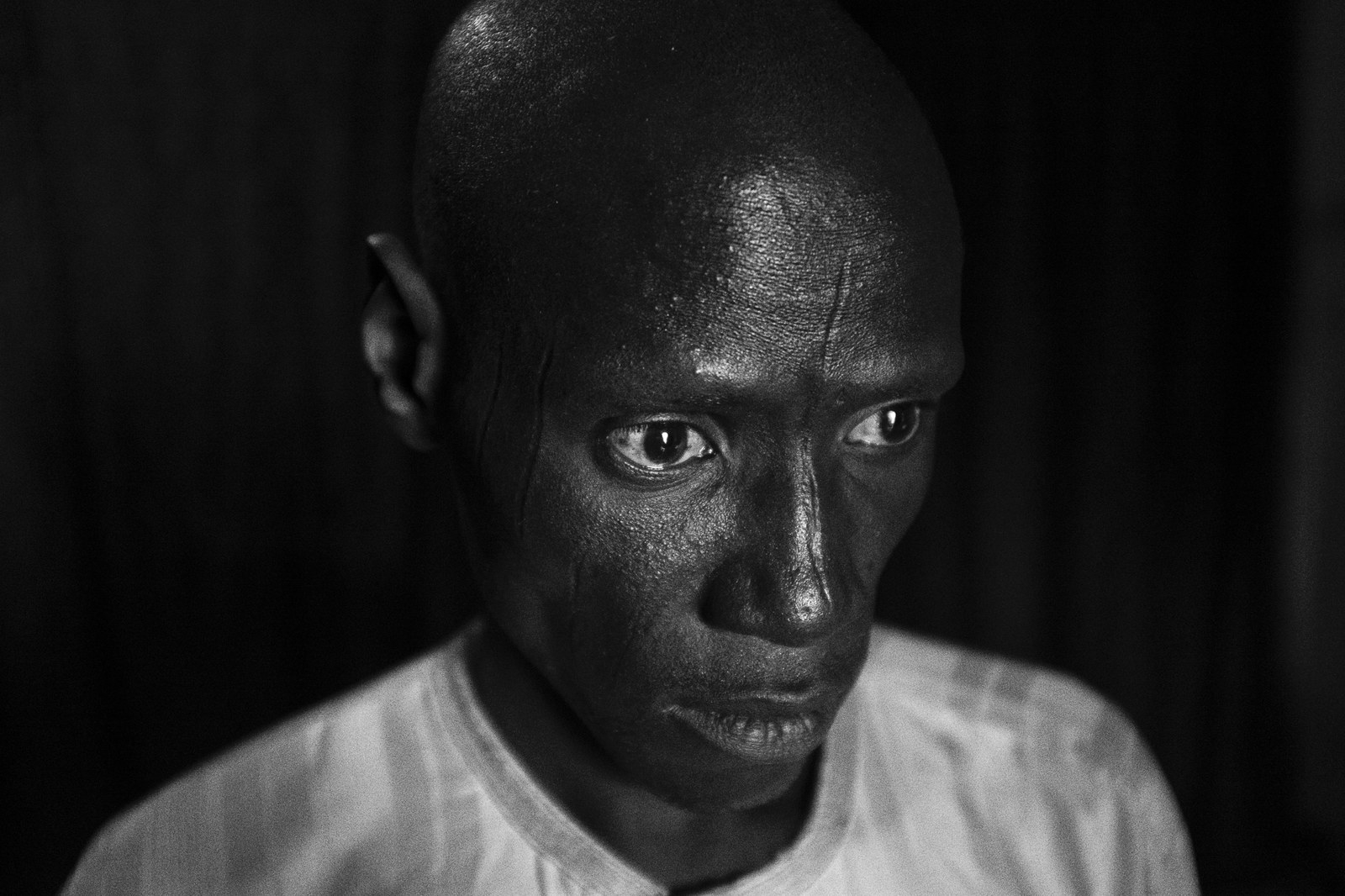

At 22 years old, Bolu, who asked to be identified only by his middle name in order to protect his identity, already had an uncommon wisdom and gentleness. But on this brisk November morning, he looked and sounded like a lost child.

His father’s professorial air, which had held steady over the chaotic last 24 hours, vanished as they sat before the sagging yellow building.

“I just kept thinking, look at this place where [my Dad] wants to come and drop me. Mehn!” he said, using a Nigerian slang exclamation of disbelief. “It was crazy. I’ve never been in this kind of place in my life.”

Bolu’s stepmother finally broke the silence. She was a nurse who every day saw the human cost of drug addiction in Nigeria. Now it had reached her own home. “We have to do this,” she told them, trying not to cry herself.

The three of them walked silently into the building.

The first sight that greeted Bolu was a man lying facedown on the concrete floor, his legs tied to a pillar in the middle of the room. “I came in and I saw someone chained. I thought this was just — you know, Nigeria, people don’t really have information on drugs — rehab is, like, for mad people. Everybody just thinks there’s mad people in here.”

In a room with busted lights and exposed wiring, Bolu filled in forms, then had a headshot and bodyshot taken. “They took my belt because I could use it as a weapon. It was like getting arrested.” Later, Bolu would learn that those who had actually been arrested — dealers and traffickers — were locked in cells on the ground floor of the center.

“They took my belt because I could use it as a weapon. It was like getting arrested.”

Sleepy-eyed and petite, Bolu was the youngest person in the rehabilitation facility. His desperate, last minute tirade to his father that he would run away if they left him here hadn’t stopped his parents from doing exactly that — tearfully. After they’d gone, he didn’t dare go downstairs. He sat on his bed and tried to calm himself. The mattress was thin enough to feel every metal spring beneath. There was a bathroom in one corner, shared between four men, with no running water.

He’d been given a yellow vest to wear at all times — “to differentiate you from the suspects,” he was told. A pale light illuminated the mold-stained blue walls. “WELCOME TO THE CONCRETE JUNGLE,” someone had scrawled in white chalk. On another wall: “MURDERFUCKER. I’M ILL, NOT SICK.”

“I just kept looking around,” Bolu said. “I cannot fathom why I’m here. Everything — like the condition of these places. It was like a ghetto.”

One by one, his three roommates trooped in and sat on their own beds. One of them was on his fourth stay in rehab; another had hallucinations brought on by toxic psychosis. Bolu had barely taken all this in, when he noticed the entrance to the room had a barred metal door.

“They locked us in the room.”

Bolu is one of millions of Nigerians dealing with addiction to tramadol — a number that’s set to soar as Africa’s most populous nation becomes increasingly hooked on the painkiller.

Less than a decade ago, beds at NDLEA facilities were filled almost exclusively with working-class people struggling to wean themselves off locally brewed alcohol, heroin, and cannabis. Those using tramadol — a synthetic opioid and cousin of powerful prescription painkillers like morphine, oxycodone, and fentanyl — were rare cases, almost entirely confined to young men doing hard labor or people who’d become addicted through medical prescriptions. “Eight years ago, I’d be surprised to see a few tramadol cases [a year],” said Audu Moses, a psychiatrist whose work with the NDLEA and a UN-sponsored clinic makes him one of a handful of addiction specialists in Nigeria. “Now, I’ll see around 10 patients in a month, and every year it’s going up.”

Today, Nigeria stands on the brink of a catastrophic epidemic. BuzzFeed News has found Nigerians of all ages are popping millions of pills daily, washing them down with codeine, another drug based on opium poppies, or as part of a cocktail that includes “purple lean” and Rohypnol, the date-rape drug. Senior military officials told BuzzFeed News that stashes of tramadol recovered from Islamist militants like Boko Haram often outnumber bullets found in their hideouts. Aid workers say it is circulating in refugee camps. College students use it as an aphrodisiac. In the rural north of the country, subsistence farmers say it keeps them going for hours on end, a phrase echoed by sex workers in southern urban centers.

Unlike heroin or morphine, tramadol isn’t eye-wateringly powerful, nor does it give extreme highs. Instead, the epidemic is being driven by its ready availability — the result of an international loophole that means manufacturers can legally produce vast, unregulated quantities in Southeast Asia, from where it’s imported to Nigeria.

Originally set up to deal with opium abuse in the 1920s, a global agency called the International Narcotics Control Board today regulates how much opioid product, including synthetic ones, each country can produce or purchase. But tramadol was first synthesized by scientists trying to minimize the risk of addiction, and a belief it successfully surmounted those pitfalls prompted the board to repeatedly designate it an “unscheduled” drug — meaning there’s no limit on production and international drugs bodies can’t track its export.

For medics in Nigeria struggling to fill a gap in pain management medication, in particular for cancer and post-surgery patients, tramadol’s “unscheduled” label made it an obvious choice. Doctors Without Borders classifies the drug an “essential medicine,” arguing that pain relief shouldn’t be a luxury in developing countries.

Yet another strange irony about tramadol: It’s precisely the drug’s lack of potency that makes it so ubiquitous.

Still, the unscheduled label has had unintended consequences. It explains how the world’s second-biggest importer of tramadol, behind only the US, is Nigeria’s tiny neighbor, Benin, whose entire population numbers less than that of the state of New York. The reason? Benin is a notorious smuggling hub — its porous borders mean drugs can flow freely into Africa’s most populous country.

Yet another strange irony about tramadol: It’s precisely the drug’s lack of potency that makes it so ubiquitous.

“Tramadol will relieve pain, but what you feel is a certain calmness, like a numbness. No one exclusively abuses tramadol — they won’t get enough out of it. They throw tramadol in as something to spice up the mix,” said a former pharmaceutical executive who spoke on condition of anonymity because of the potential repercussions for anyone publicly criticizing government inaction. Instead, tramadol’s abuse is tied to codeine, prescriptions for which pharmacists have been lobbying to reduce for years. “We’ve been saying to doctors, who are the only ones who can prescribe it, stop prescribing goddamn cough syrup. The issue here is that prescribers don’t want to erode their profit margins, and tramadol is in turn marketed to them by the pharmaceutical industry.”

As in the US, officials in Nigeria caught on the back foot have scrambled to find quick-fix solutions after years watching a slow-burn epidemic. In May, lawmakers stung into action by the growing public awareness of codeine abuse announced a ban on the production and importation of the cough syrup. Officials touted the move as a solution to the twin epidemics of codeine and tramadol abuse.

When approached for comment, Nafdac, the agency charged with regulating tramadol, told BuzzFeed News they were on strike and couldn’t comment. Two numbers for the Medical and Dental Council of Nigeria repeatedly went unanswered.

Again, just like in the US, where a lack of insurance leaves millions of impoverished people with addiction lacking access to care, most people with addiction in Nigeria’s 190-million strong population struggle to find the kind of ongoing support addiction requires amid the country’s bare-bones health care system. For those dealing with chronic mental illnesses, the consequences can be disastrous.

“What do we do with an army of young people who don’t have a future?”

In theory, Bolu was fortunate to fall onto the state’s radar, but studies show that the kind of sudden-withdrawal detox offered by the NDLEA doesn’t work very well to treat addiction — and in fact may set people up for tragic outcomes if support isn’t continuous. It takes around two years for the brain to adjust to coming off opioids, but those coming out of detox have a lowered tolerance, meaning relapses are potentially fatal. Instead, the US federal government recommends medication-assisted treatment over detox.

In Nigeria, with the state unable to provide a support network, it’s falling on local communities to pick up the pieces. Many people with addiction turn to churches and mosques instead. Moses, the psychiatrist, said that the country’s few clinics weren’t capable of stemming the tide of addiction.

“Tramadol affects memory. So [these kids] can’t continue work, they can’t go back to school. And even when they learn some skills, they can’t concentrate, so they give up on contributing to society. Some of them will die.”

He spread his hands in a gesture of futility.

“What do we do with an army of young people who don’t have a future?”

The most bewildering part, the thing Bolu turns in his mind in the lonely, sweltering hours of the night, was that he’d never been into drugs, barely even liked alcohol.

The troubles he faced in his life didn’t stand out at all to him, especially not by Nigerian standards. Coming from a comfortable background in many ways cushioned him from the harshness of life in one of the world’s most corrupt countries, and he’d bought into the ingrained Nigerian belief that being financially comfortable meant he couldn’t really have any problems.

He was the second of four siblings, all close. They’d grown up in Jos, a verdant, hilly city in the center of the country. There were holiday houses across Nigeria, and opportunities to travel abroad — the US, and London — if he’d wanted them. Once he turned 13, there was enough money for him to follow in the footsteps of his older sister and go to private boarding schools.

But there had been real tragedy in Bolu’s life. His mother killed herself the day before he started high school in September 2007. His father remarried three years later, adding four new stepsiblings to their still-grieving family.

Bolu’s father and stepmother were loving, and between their jobs as a university professor and nurse, he’d never felt he lacked for anything.

And so the question replayed over and over: How did he get so lost?

The first wrong turn came three years ago, shortly after he turned 18. Popular and excelling in class, Bolu got the grades he needed to get into the University of Ibadan, 850 kilometres southwest of Jos, just outside the megapolis of Lagos.

That was when girls came onto the scene.

“I don’t know — I think everybody just found out about it, somehow, somehow. We’d all be drinking, then somebody will tell you that oh, use tramadol, you’ll last longer.”

Bolu had a new girlfriend, and it seemed like a no-brainer. Before a date he popped a 55-milligram pill. It felt good.

“Nothing,” was all he knew about the downsides of the drug. “I just knew that it helps sexual performance. That was all I knew.”

The side effects kicked in after five or six months. The itching came first, and was the worst. It felt like bugs crawling up his arms and legs. “I was very restless. I couldn’t focus on anything for long periods of time. I’d sleep off at weird times, anytime.”

At first, it was just in social situations. “Then later on, just anywhere. In class if I needed a boost. In the library. After meals.”

Initially Bolu wasn’t that concerned. “I thought that was part of the whole package. It’s the drugs, mehn, that’s part of it. It came with the nice feelings, too.”

His dosage crept upwards, even after the girlfriends dropped out of his life. Soon he was taking two 55-milligram pills. It was easy to get them from street peddlers around campus — someone in the dorms always had them. He’d carry around two “cards” of pills — “so if I was using, I’d pass one to whoever was around me” — and a bottle of water to deal with the dehydration brought on by the codeine he washed it down with. He switched to a 225-milligram capsule. When that was no longer sufficient, he upped it to two 225-milligram tablets.

At first, it was just in social situations. “Then later on, just anywhere. In class if I needed a boost. In the library. After meals.” Next, he began adding more drugs into the mix: sometimes marijuana, often codeine and Rohypnol, the notorious date rape drug, all washed down with alcohol. But all of them were side dishes to the tramadol that blunted reality, making each day easier to digest.

Outwardly, the difference in his behavior was imperceptible. “I’m not loud, I’m calm. I wasn’t displaying anything, so nobody noticed. For a long time, I was able to hide it.”

Inwardly, though, his life was slowly coming off the rails. He hardly attended classes anymore. Once the drugs wore off, his anxiety about the hole he was in was crippling. “You say, ok, I’m not gonna do drugs today. Then something triggers you and then around 4 o’clock, 5 o’clock,” he mimed tossing back a handful.

“I wanted to stop, but at the same time I felt like I couldn’t. I didn’t tell anybody because I was scared that they would judge me.”

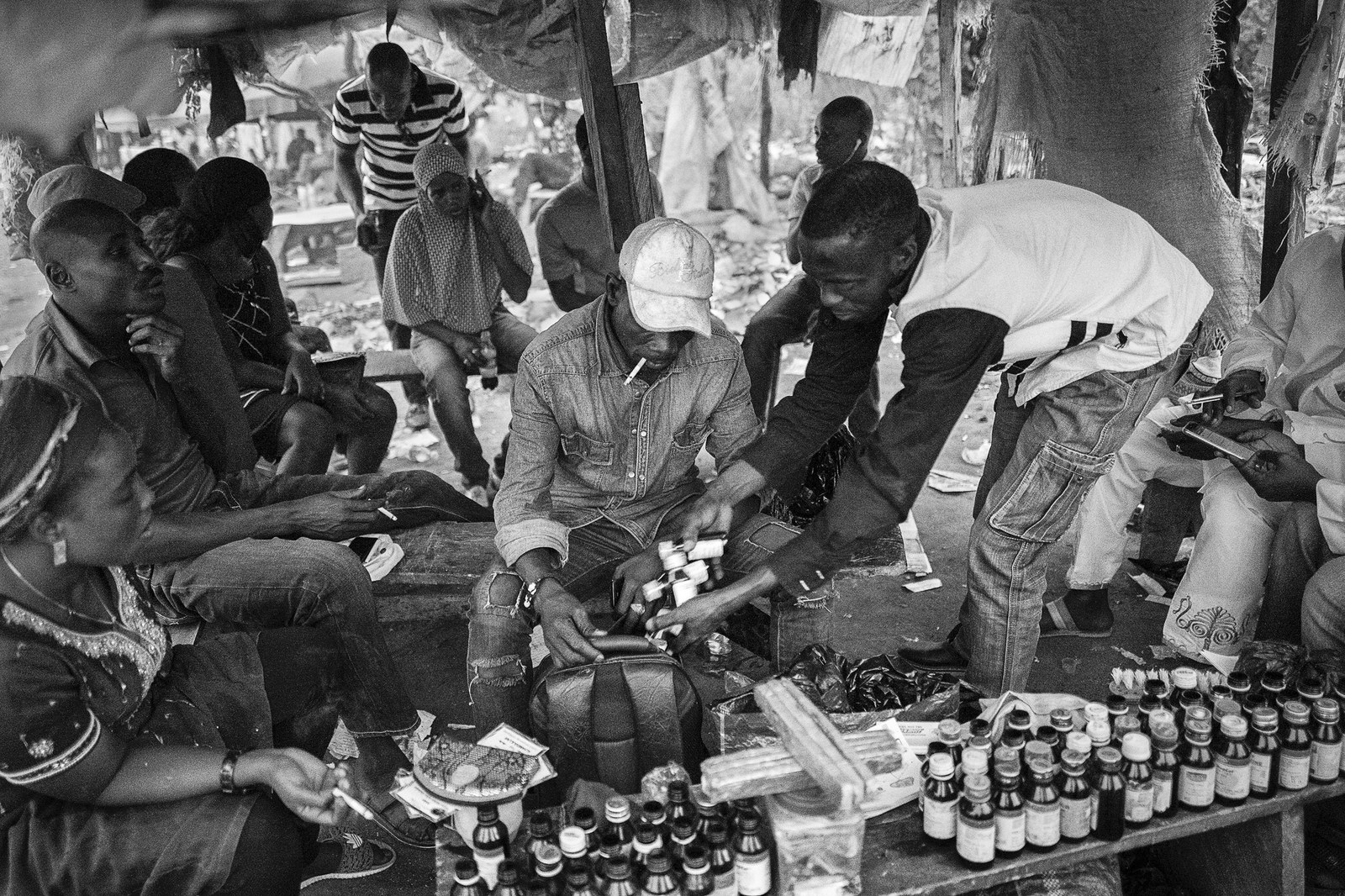

Nashru, a stocky, brooding man in his forties, sat beneath a plastic-covered wooden shack that served as a storefront, and watched through hooded eyes as a steady stream of customers came to score in Apo Park in Abuja.

Fuelled by oil money, on the surface the capital is a shiny, moneyed hub; but off its sleek highways, on city outskirts and in neighborhoods that were never planned but sprang up out of necessity, workers and commuters live in abject poverty.

Amid the scrubs and trash of Apo Park, drug dealers like Nashru had carved out their little territories. The tools of his trade were spread out on the bench in front of him: tins of pills, dozens of bottles of codeine, knives, powders. It is here that Nigeria’s poorest people with addiction — in a country where more than 80% of the population lives on less than $2 a day — come to get their fix. At less than 40 cents a pill, tramadol is an escape cheaper than alcohol.

Along came a pair of giggling teenage girls who wanted a discount on their bulk buy of pills; a middle-aged woman who wanted tramadol and “Arizona — the baddest weed”; a sex worker who needed pills before starting work; a senior police officer who wanted pills and his weekly bribe money for not arresting the dealers; and a boy of barely 16, who carefully handed over four dirt-stained notes.

Nashru dished out the drugs without a word. Beside him, his assistant, an elderly man, rolled up and handed out spliffs or codeine whenever the conversation got heated between the regulars.

Almost all the regulars are employed — using tramadol to push through long, physically demanding, low-paid jobs.

Among them was Adams Jibril, 24, who grew up 240 miles northeast of Abuja, in a small rural community called Tafewa Balewa. Tired of watching his impoverished family scrape together their meager earnings as crop farmers, Jibril left home at 16 to find better prospects in the capital. But there were few options for a high school dropout, and he wound up working 18-hour shifts as a security guard. His employers provided rent-free “accommodation” — a coffin-sized box with lying-down space only. He sent most of his 16,000 naira ($45) paycheck back home to his six younger siblings. “Of course I provide — I’m a man, I should do that,” he said.

There were many things Jibril felt he had to do, as a man.

He wanted to join his friends playing soccer after work, a rare opportunity to unwind and socialise. But the exhausting work hours left him listless. “The first time I took tramadol was at the football pitch. It was a friend that advised me,” he said, one evening on a night out with his girlfriend, Stella Maries.

“He say that if I take tramadol for my tiredness, I will be okay,” Jibril said, in faltering English.

It worked — that day, he played the best soccer of his life, he recalled. “People were saying, this guy, he is so agile, so strong,” he said.

It worked so well, in fact, he decided to start taking tramadol on the job. It eased his tiredness on the long shifts. Soon he was on 600 milligrams a day, an amount significantly above recommended US prescriptions for severe pain. But then, when he tried cutting back, he noticed a scary side effect. “You feel sick, shivering — all your joints will be weak.”

The more he cut down on pills, the more his joints ached. Jibril was experiencing a common side effect of opioid abuse: Users develop such a high tolerance that they effectively begin to suffer withdrawal pains at their older, lower doses. Playing soccer was soon out of the question. So he began spending more time with Stella Maries, and that involved being a man in other ways.

“Before I was taking it for tiredness,” was how he saw it. “Now when I want to meet my woman, I want to have joy.” He passed a bottle of codeine to Stella Maries under the plastic table. With feigned casualness, she took a deep swig then handed it back. Her leg bounced up and down because, she said, she was impatient to get to a party they were going to.

That’s the story Jibril tells, and it’s the one that everyone in the park understands, a variation of their own story.

“If I want to, I can stop it,” he said. “It’s a matter of time. Everything is time. So when God says he will stop all this” — he meant the endless days living in a cramped box of a room — “I will throw that rubbish away.”

He stopped talking and exhaled deeply. He believed that the cure, ultimately, was simple. In a country propped up on aspirations to get rich, there was only one answer. “If I had money, I would never do drugs,” he said.

A tinny radio was playing at the park in Apo and evening was approaching. Cars speeding along the highway headed home. Herdsmen led their cows slowly past, not stopping here.

By now the regulars kept knocking over the table. Someone opened a tin with shaking hands and a spray of pills fell on the dusty floor. Nashru’s assistant shrieked, lunged to the floor, and tenderly placed each one back in the tin can.

A group of boys finished playing soccer a few dozen yards away, packed up, and left, taking the tinny radio playing ragga with them.

Only those sitting under Nashru’s tent remained as the light faded.

Bolu’s first overdose came at him out of nowhere. For two hours, he lay on the floor of his college room, conscious but paralyzed, unable to lift a finger even to clear the foam filling his mouth.

“My heart was beating really fast. I could not shout. I couldn’t stand. I could not do anything. I thought I was dead. I lay down there for like two hours.”

It was a Friday in May last year, the day after he finished his first-year exams — the first step to earning a law degree — and he’d decided to celebrate with friends that night. He hadn’t done any drugs in the week leading up to exams, and, his thinking went, that in itself was a cause for celebration. Soon after waking up, before a single friend had arrived, he’d opened the first blister of tramadol.

“I had a lot of pills in that room, I had a bottle of codeine, a lot of weed. First I popped pills. Then I drank half a bottle of codeine. Then I started smoking. And then — I don’t know what happened, but I dropped. I started convulsing.”

On its own tramadol is rarely fatal, even in overdose quantities. Mixed with other drugs, though, it can become a sedative powerful enough to stop the heart.

First created in the 1970s by German scientists, it was initially seen as a wonder drug, ideal for combatting post-surgery pain without the downside of addiction. Early research emphasized tramal, as it was then called, had a “low potential for abuse” — a description that continues to accompany studies today.

What those early tests missed was that tramadol’s reaction depends on how it’s taken. Researchers assumed that tramadol would be most powerful when taken intravenously, as is the case with most opiates, including heroin and morphine, so they focused on results when the drug is injected.

As the scale of addiction grew, scientists began probing that assumption. They discovered that, unusually, tramadol is far more effective when taken orally — for some, tablets can be as powerful as morphine. In Nigeria, 70% of all those in rehab for opioid abuse used tramadol as their drug of choice.

When Bolu came to, he crawled to his bed, exhausted. “I was just like, wow, this is crazy. I want to stop this. I was really tired. Of everything.”

And for a while, he did stop. “I was so scared that I gave up for like a month.”

But back in college for his second year, last September, a downward spiral began again. His grades plunged, and he barely attended classes. He’d thought it was time to go home and reset for a few weeks; instead, it was impossible to hide how much drugs were derailing his life.

His parents puzzled over his strange moods. He argued constantly with his siblings. Friends wondered what was wrong. Once or twice, when he’d offer them one of the two tablets he constantly carried, they’d give him pitying looks that stung. But Bolu’s days narrowed to the moments he could take the pills; everything else was a distraction.

Leading a double life began to take a toll. “Everybody was asking me what was wrong, and I was lying so much I couldn’t keep up with the lies. I was sick this day, I was depressed this other day. Some days that I was supposed to be sick, I forgot I was supposed to be sick.”

Bolu comes from a sprawling family, a mishmash of cousins and aunts and uncles who were all close. Everyone had a suggestion or explanation. An uncle said he should he travel abroad, to the UK or US. An aunt who lived near the campus wanted him to stay with her during term time.

The attempts to rescue him only served to irritate him further, and Bolu stopped turning up to family events altogether. “One thing led to another and everybody eventually put two and two together.”

What followed was a blur of lies, guilt, and shame that littered the path to rehab.

“A lot of things I was doing at that time weren’t making any sense to me anymore. I was fucking up my relationships, in school, my family — everything was suffering,” he spoke in a flat, monotone voice. “The thing that was getting to me more was the fact I couldn’t control it. I couldn’t say that today, I’m not going to do drugs, because I just couldn’t. I had to do it. I just had to. I couldn’t do anything without using drugs, and I hated it.”

He returned to college. At least there he could do his drugs alone, in peace.

And then came the November evening where his terrified brother, who was at the same college, found him writhing on the floor in the grip of another overdose. The next day, Bolu called his father. The conversation was short: He needed help. Please. And so his father had flown to Lagos, then driven to Ibadan to pick him up. A day later, he’d ended up at the NDLEA clinic, checked in for a four-month stay.

In the confusing weeks that followed, he focused on learning a new language that offered an explanation. A counsellor had explained the meaning of “triggers.” Another one had explained what dissociation was.

So maybe his mother’s death had been a trigger he’d buried, he realized. Maybe when he wasn’t feeling anything, just emptiness, he was dissociated.

He’d started writing to try to make sense of his feelings, and once he’d written in his diary: “When I see the amount of issues that people have to deal with, I feel ungrateful for my ‘smaller’ less ‘significant’ problems. So I came up with a [solution]. I'd only cry in the rain... because the water does not remember my moments of weakness and does not hold them against me.”

Allowing himself to admit his feelings was a start.

In April, a court case began against a notorious drug baron who’d set up shop a few miles from the rehab center. Jude Okoye, a 58-year-old patent medicine salesperson who went by the alias Zuma, had been busted by NDLEA officers three times, most recently in a parking lot last June. At his trial, prosecutors read out a long charge sheet of drugs they’d found in Okoye’s warehouse: syringes; 1.3 tons of tramadol; 16 kilograms of pentazocine, a drug that creates similar highs to morphine; and labels with forged expiration dates on them.

The tramadol haul from that single bust was roughly four times the amount seized across sub-Saharan Africa in 2013.

“The frightening aspect,” the prosecutor noted in court documents, “is that most of these hard drugs found in the accused’s possession are expired drugs, which when [they] found their ways into the market would have posed serious danger to the lives of innocent people of Nigeria.”

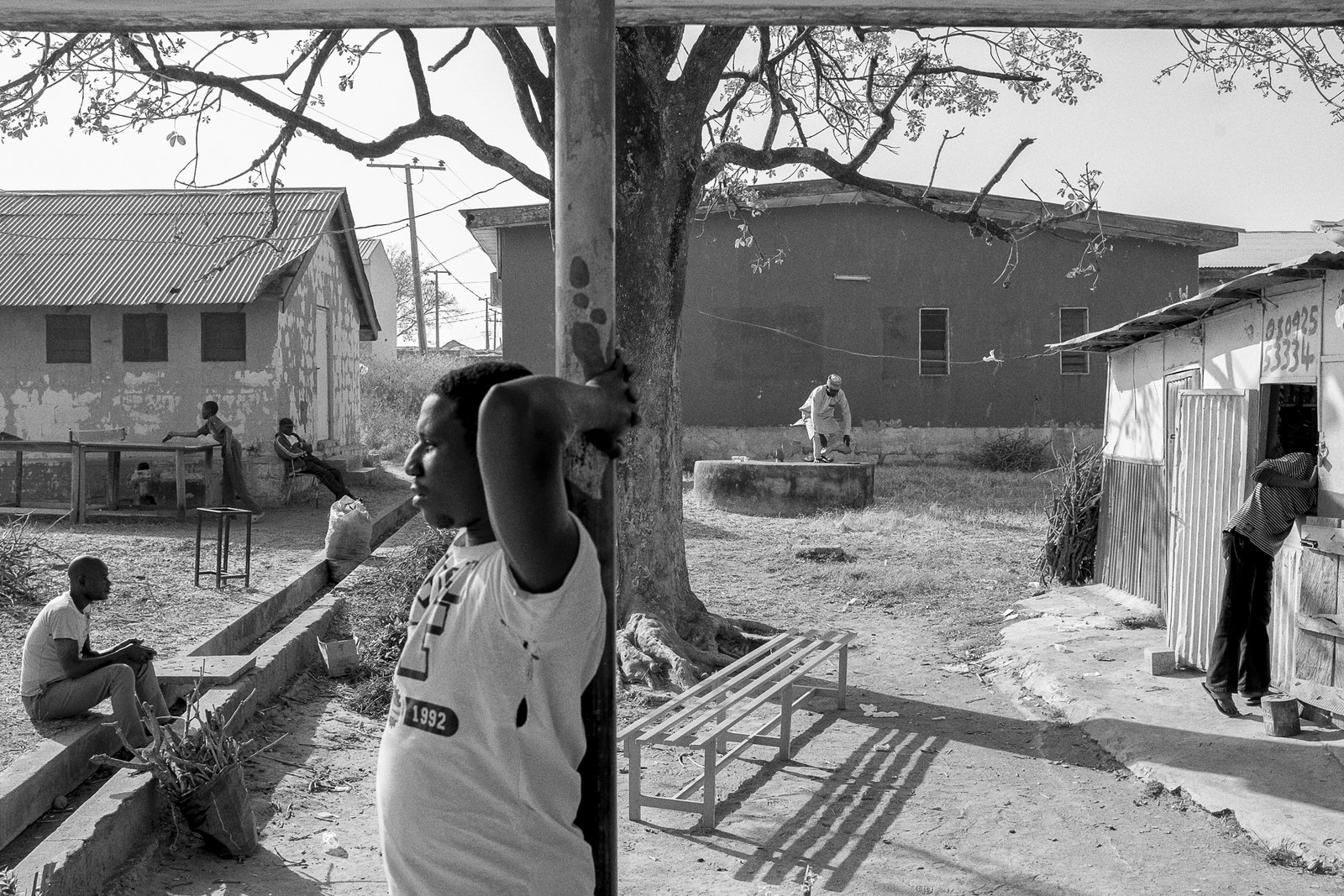

Those who end up in one of the NDLEA’s handful of beds nationwide are, technically, the lucky ones.

Officials say it’s not just the size of the hauls that are alarming. When busts are made, rather than the 50 milligrams typically sold in pharmacies, wraps often contain 225-milligram pills. That’s close to what’s considered a safe upper limit in the US for severe pain — in a single pill.

And yet, stop and ask your average Nigerian in the street what they think of addiction, and odds are they’ll label it a moral failing, or an affliction of criminals or “lunatics.” That outlook characterizes the official approach, too. Struggling to shake off the “lunatic asylums” label slapped on psychiatric wards until the 1960s, mental health patients are still routinely classified as “inmates” who are “detained” until they can be “released” back into the general population.

Bolu wasn’t crazy, and he’d never committed a crime — he had a ready-made reason for denial.

Until he wound up here, it had never occurred to him that he needed psychiatric help.

“That’s the problem. Until people realize that they’re really traumatized and they’re using this to escape, we can’t help them,” said Moses, the psychiatrist.

When the NDLEA was set up in 1990, it included an ahead-of-its time way of curbing drug smuggling and abuse: rehabilitation centers run under its “drug demand reduction” units.

But the corruption that so defines Nigeria seeped into the agency, too. Mismanagement and a lack of resources left it hobbled in almost every arena. Training is almost nonexistent or — when it does come — antiquated.

“We are under-resourced,” Naomi Enessbee, the center's co-director who doubles as a counsellor assigned to Bolu, said matter-of-factly, sitting in an office at the clinic one afternoon in February. Patients at the clinic are not supposed to go cold turkey, but they have no drugs to help ease withdrawal symptoms. On top of that, the power was out because, despite decades of oil money, Nigeria still doesn’t have regular electricity. The backup generator wasn’t switched on because federal funding didn’t cover the expense of buying fuel. And because there was no regular power, it made no sense to bother with computers, which was why patients’ records sat in dusty folders hand-written with green permanent markers.

Still, those who end up in one of the NDLEA’s handful of beds nationwide are, technically, the lucky ones. For all the rehab center’s failings, it was there that Bolu was learning to unravel some of the untruths about mental health that society had drummed into him, chief among them that addiction was a personal failing. In many ways, the best lessons he learned came from seeing how those around him were pushed aside by a society which doesn’t have the resources to deal with addiction.

When other residents would attack the counsellors or security guards, Bolu stayed clear of them. He soon learned to distance himself from the fights that broke out when the frustration of being locked in a dorm for 12 hours while detoxing bubbled over. And he avoided those who would arrange to sneak drugs into the building, convincing guilt-ridden relatives that this hit would be their last one, and what difference would one final toke make in there anyway?

“This was like a wake-up call, like, shit can really get real."

“This was like a wake-up call, like, shit can really get real. At any point. Like, I’ve met enough people here, so I know that this thing can make you go psycho. You can just waste out your life,” was how he put it.

Each time someone was tied up, as he’d seen on his first day, it shocked him a little less. “You could see the buildup to why things like that had to happen,” he said, meaning the lack of alternatives to secure both the offender and others around them. “You could also reason [why] people were having fights. Or someone might have gotten drugs somehow. You could see that this was the action, and this was the consequence. It was just a direct line.”

So the thought would circle back to himself. That action was why he’d ended up here, in this bed, listening to the sounds of the night and unable to sleep.

The more he learned about others, the more Bolu understood himself.

He’d seen people come in, leave, and a week or two later they’d be back. The man who slept in the bed next to him was on his fourth return. Night after night, Bolu wondered: Would that be him one day? What changes could he make to make sure it wasn’t him?

Somehow, Bolu had survived the nights of cravings so intense he couldn’t sleep. One day after another had passed, and now he had been clean for 97 days and it was a Friday morning in February, three weeks before he was due to be discharged. Enessbee, a kind counsellor who for five years had helped everyone from gang members to ambassadors’ sons, was talking to him about his impending departure, which had been weighing on Bolu’s mind.

“I’m scared that I might be strong here, and then I’ll go out and see somebody using,” Bolu told her quietly.

Another of his counsellors had taught him “the five D’s,” which he ticked off on his fingers to remind himself: “Distract yourself, drink some water, take deep breaths,” Bolu began, then stopped. He couldn’t remember the other ones; the drugs meant his memory was often tattered. But it didn’t matter anyway. Today was one of those afternoons when everything seemed like a struggle.

That morning, it was sunny, and Bolu had been feeling good. He’d gone outside to use the public taps since there was no running water in the center, and as he was returning, he had seen a man standing by the gate.

“I saw this keke [tuk-tuk] driver smoking,” he said. “I just looked at him. I won’t lie — I had cravings.” He felt bewildered once again at how easily three months of work had seemed to come undone.

"I’m not a bad person; I just made bad choices.”

“This is a controlled environment,” he said. “But outside? There’s everything that you left. Everything will come back at once, and the world doesn’t really wait for you to get your shit together.”

He was adjusting slowly to the new normal that might be waiting outside, even if it was hard to gauge that from here. “With my family, there’s a trust issue. I don’t blame them,” he said.

Bolu would need to come up with a story that somehow explained everything, because there would be questions from friends. “They don’t even know I’m here,” he said, exhaling deeply. “I just left one day, and I switched off my phone from that day.”

That had been hard to think about. Most of his friends could pop an occasional pill, drink a bit too much, and not become addicted. Bolu had learned the hard way that he couldn’t. “I know I need to find new friends, but I’m not excited about the prospect because those people, they’re not bad people. Just like I’m not a bad person; I just made bad choices.”

And the consequence of rehab was, he reminded himself, that there were glimmers in the wreckage, lifelines from the foundations he’d built before drugs consumed everything.

“I’ll go back to studying — I have something to look forward to. Yeah. I feel very — a small, a tiny amount hopeful,” he said. “I’ll see how that works out for me.” ●