ABUJA, Nigeria — Of all the memorabilia he's collected during his nine trips to the Democratic People's Republic of Korea, Alhassan Muhammad treasures one most: The 54-year-old Nigerian lecturer keeps his “Friends of North Korea” medal lovingly stowed in a bedside cupboard.

A chatty professor of environmental sciences at the University of Abuja, Muhammad is one of just four Africans to have been given the award, and he flashes a wide smile as he recalls picking up the medal five years ago. “I go there twice each year, and I always make sure one visit is on September 9 because that’s their independence day celebration.”

Muhammad is the enthusiastic patriarch of a tenacious handful of Nigerians who believe that transplanting North Korea’s political system — an all-encompassing ideology called Juche, imposed by the country’s founding dictator in the 1950s — is the key to unlocking the potential of Africa’s most populous nation.

On a sweltering Tuesday morning in May, he welcomed me into his ground-floor flat in the capital of Abuja. “North Korea is a country that’s resilient, and built on the basis of self-reliance. It's very peaceful. It’s a country that is so disciplined. Those are the things that attracted us to the tenets of our darling state of North Korea,” he said, as outside a cacophony of car horns shrieked and hawkers skirted traffic. “The inequality coming from right-wing capitalism — I’m so uncomfortable with that.”

His home, in a building with gently peeling walls, managed to be both typically Nigerian and a shrine of sorts to North Korea. Puffy sofas were crammed around a patterned rug, fake flowers dotted the room, and decorative balls sat in a glass case. The power was out, as usual, and outside the muezzin call to prayer rose and fell.

There’s a North Korean law that every household must display portraits of their leaders in their homes, and the 7,000 mile distance from Pyongyang wasn’t going to stop Muhammad from following it. He gestured at two photographs that take pride of place on his living room wall.

“This is the founding father of the Democratic People’s Republic of North Korea, His Excellency Comrade Kim Il Sung,” he said, pointing at the first framed portrait.

“That’s my wife, Khadija,” he continued, as a woman in a glittering yellow hijab walked into the room.

“And this,” he said, turning back to the wall, “is His Excellency Kim Jong Il.”

He beamed at the former leader of North Korea, who scowled back from beneath his perpetual upturned bowl haircut.

Juche supporters still scattered across Africa today are the tail end of what was once a brightly burning comet of support for North Korea on the continent. As the region began wrestling free from colonialism in the 1960s, many saw their struggles as newly independent nations reflected in the North’s fierce nationalism against US-backed forces. Socialist parties springing up across the continent forged ties with North Korea, from the Central African nation of Equatorial Guinea — where the country’s then-dictator renamed the only legal party after North Korea’s Worker’s Party — to Guinea, formerly a West African showcase of Marxism.

Crucially, this cooperation came with aid and military support. If you stumble across a distinctly Asian-looking, Communist-style statue in an African capital, it was likely built by North Koreans during the Cold War. In Somalia, a consignment of bulldozers and tractors arrived as a personal gift from Kim Il Sung; in Burundi, North Korean engineers built a presidential palace; and in Zimbabwe, North Korean-trained soldiers fought colonial leaders.

But nowhere does Juche’s promise of order still resonate so much as in Nigeria, where the four North Korean–themed societies that Muhammad juggles have drawn some 2,000 members.

Which explains how a slice of North Korea ended up in the otherwise ordinary Nigerian home of a man who has dedicated the last decade to promoting the secretive state. A red paper lantern hung over the dining table, itself draped with a red-dragon-patterned tablecloth, and down the hallway a red lamp spluttered on and off in time to the power cuts. Issue number 715 of North Korea’s official state magazine — the cover splash showed the founding father in military uniform inspecting a flag — could be found alongside his wife’s magazine on jewel-bright African fabrics. He apologized that it was an old issue -- he’d taken the more recent ones to campus; his wife apologized that her magazine was an old issue too -- shipments of international magazines are often erratic in Nigeria.

“I’m not saying Nigerians should be exactly like Koreans — look at me, the way I am,” Muhammad said, spreading his arms so the silk folds of his traditional blue boubou cascaded gracefully. “I’m so proud of my indigenous culture. But common sense dictates that if your neighbor is doing something good, you should imbibe those good aspects and then you’re better off.”

Founded by Kim Il Sung — who declared himself the “eternal president” — the “Juche Idea” was based on a mishmash of ideologies borrowed from Mao’s China and Stalinist policy, all designed to cement Kim Il Sung’s position as an unparalleled genius and spur a Korean-centered revolution.

At its core are two slogans: “man is the author of his own destiny,” and a nationalistic battle cry that all nations should be built on the basis of “the spirit of self-reliance.”

“This lets people fill in the gaps as they see fit and … apply the idea to their own circumstances. This can be at the personal level, too,” said Andray Abrahamian, who has seen such instances first hand as associate director of Choson Exchange, an organization that holds workshops in Pyongyang for North Korean entrepreneurs.

Home to 180 million people from 250 ethnicities, who speak more than 500 languages, Nigeria perpetually languishes in the bottom fifth of inequality leagues and regularly tops global corruption perception indexes. For some, the draw of Juche is a philosophy underpinning an ostensibly unified nation, ruled by a single party, and in which many of its 25 million citizens have government-approved haircuts and wear government-issued outfits.

Juche helped drive North Korea’s rapid economic growth in the early days. “In the 1970s [North Korea] began to try to export Juche and say, 'Look, we’ve got this idea: If you’re a third world, postcolonial country, you don’t have to align with Russia, America, or China. There’s an alternative we’re offering you,'” said Owen Miller, a lecturer in Korean Studies at the University of London’s School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS). “On the surface you can see how it appealed to a lot of post-colonial countries. But once you get beyond that, there’s not a lot to it.”

By the 1990s, a series of crippling famines compounded by bad governance meant North Korea turned even more isolated and secretive. Exporting Juche fell to the wayside.

“What stayed behind is these networks that still operate, and they’re called friendship societies,” explained Hazel Smith, a professor at SOAS's Centre of Korean Studies.

These societies exist all over the world, although some “consist of two or three people with grandiose names,” Smith added.

Muhammad, who founded the Nigerian-DPRK Friendship Association six years ago, says there are at least two Juche adherents in every African country today. But hundreds of Nigerian fans remain unshakable in their faith, cheering on the country’s nuclear ambitions in what they see as the plucky underdog facing up to a bullying United States.

Since Donald Trump’s election, current ruler Kim Jong Un has carried out a number of missile launches in response to what he’s called the US president’s “maniacal military provocations.” Trump, meanwhile, has warned a “major, major conflict” with the North is possible in an increasingly noisy standoff between the two volatile leaders. The North has proudly publicized its plans to develop a missile capable of striking the US, and accordingly continued testing long-range missiles.

Back in his Korean-themed living room, Muhammad rolled his eyes at the idea of a nuclear confrontation. “Of course they’re testing,” he said evenly. “Just like any other country, they have the right. You can’t be doing something and then you want to stop others from doing it.”

Trump, he noted, had flip-flopped between praising Kim Jong Un as “a smart cookie” whom he’d be “honored” to meet, to deriding him as “a madman with nuclear weapons.”

“Donald Trump is not a man you can take seriously,” Muhammad said.

Curious as to what the official North Korean stance might be, I decided to try heading to their embassy in Abuja. There aren’t many around — the US’s 50 diplomatic posts in Africa alone are more than the total North Korean ones in the world — and it proved to be unusual in other ways. An hour of scouring online failed to turn up an official website or working phone number for the embassy.

On a sunny Friday morning, I picked one of the various, conflicting addresses the internet had thrown up, and drove downtown. The residence was indistinguishable from all the other nondescript buildings hulking behind electronic gates and razor wire. The only noticeable difference was a marble display filled with snapshots of the Worker’s Party of Korea’s seventh congress.

That, and the fact that three rubbish collectors in orange jumpsuits were milling around the entrance. One was pressing repeatedly on the doorbell. “They’re not opening the gate for us,” he said.

“Again,” his colleague said, in a bored voice.

“They dey for upstairs (they’re upstairs),” the third one replied, somewhat ominously. After hanging around for a few more moments, they drove off.

A short while later, a white bus carrying Korean schoolchildren pulled up. The driver beeped his horn. The door remained shut. He got out of the bus and banged on the gate. He sighed and pulled out a cell phone. A few minutes later, the gate creaked open a few inches. A woman’s head popped out. She looked like she’d been interrupted in the middle of cooking.

While the school bus drove in, I asked if I could make an appointment to speak with the ambassador. The woman pulled out a phone and passed it to me. “The ambassador is away, try coming back on Monday,” a Korean voice tinged with an American accent told me.

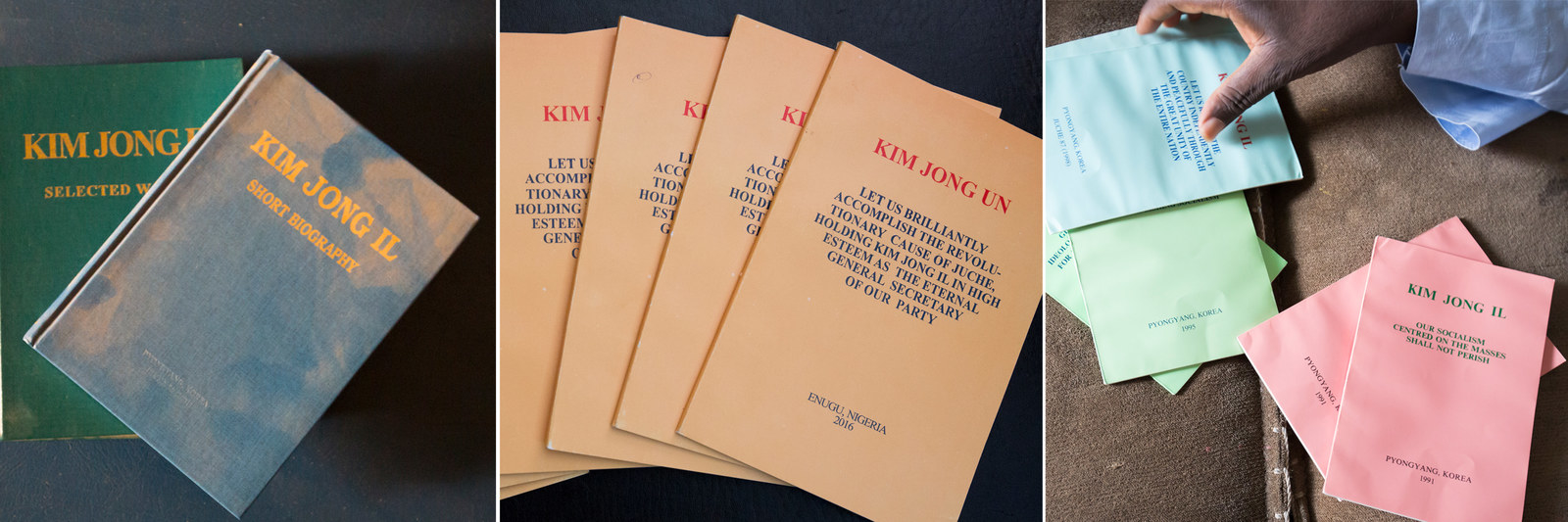

Although my attempt at entering the embassy failed, I was able to meet someone who does have regular access: a cheerful, round-faced journalist who goes by the nickname Doc (he asked not to be identified, worried that being linked with North Korea might jeopardize his work). We met at his cluttered office on a quiet street in central Abuja, where he was barely visible behind the stacks of papers and books on his desk. One pile consisted of dozens of orange pamphlets.

LET US BRILLIANTLY ACCOMPLISH THE REVOLUTIONARY CAUSE OF JUCHE, HOLDING KIM JONG IL IN HIGH ESTEEM AS THE ETERNAL GENERAL SECRETARY OF OUR PARTY, the cover read. It’s a manifesto written by Kim Jong Un, copies of which had been printed in the southeastern Nigerian publishing hub of Enugu.

One such pamphlet first caught Doc’s eye in 2002, during one of the regular meetings the various associations hold across universities. “I went through some … and I imagined if Nigerians could think alike, this country could be a lovely country.”

Discarding the parts about Kim Il Sung being a semidivine being — dozens of Christian booklets also littered his desk — he devoured the pamphlets. The more he learned of Kimsungilism, as it’s also known, the more he liked it as a philosophy.

News of state-sanctioned atrocities — mass starvation and the repression of human rights — didn’t deter him. It reminded him, in fact, of the way the Western media covered Africa, invariably presenting it as a monolith constantly plagued with disease and famine.

“Very one-sided. And news is like a miniskirt — short enough to show off vital spots, and equally long enough to cover vital spots,” was how he put it. “There are elements that may be true, but there are equally many sides that are not painted the way they should be.”

As Doc climbed the association’s hierarchy high enough to start attending meetings in the Korean embassy, he noticed something else that appealed. “Assuming a new consular comes up, he will continue exactly from where the other person left. It’s a contrast to our system, where anybody can wake up and decide that he wants to do one thing or say anything he likes.”

Doc has plans to visit North Korea: “You know, reading up a philosophy is one thing. Observing the implications and practice is another.”

There’s a story Muhammad likes to share, of an encounter during his sixth visit to North Korea. It was August 2008, and he was on a bus back to the capital after a day trip to Kaesong, a border city some 135 kilometers from Pyongyang.

As Muhammad tells it, out of nowhere they passed a group of farmers celebrating on the road. They asked their interpreters, who accompany all foreigners during trips, if they could stop. The interpreters had no problem doing so: “They’re there just to help you interact, after all.”

It turned out to be the anniversary of the day when the founding father of North Korea had been touring around the country, and happened to stop at that village. He’d dispensed crucial agricultural advice, causing the village’s crop yields to soar. The grateful villagers commemorated this event every year.

“They told us we can join them, share their food, and celebrate with them if we’re not in a rush. And we did.”

This proved, Muhammad concluded, that citizens were free to interact and do whatever they wanted with whomever they wanted. And also that reports of famines were exaggerated.

I said I didn’t doubt millions of North Koreans were going about ordinary life like anywhere else, but this sounded like a transparently orchestrated situation.

Muhammad sighed. “This was an impromptu interaction!”

His vision of the DPRK as a utopia appeared immovable.

More than once — usually when he used the phrase “our darling North Korea” — I wondered if his conviction was genuine. But then he’d reel off a list of facts and figures that suggested he knew the country’s history by heart.

Was I aware, for example, that Pyongyang has one of the deepest subways in the world — “operational since 1967” — and that some of them are used as bomb shelters? He gave a remarkably detailed history of what led to the Korean War, the recounting of which took a full half hour and during which he ran through the names of minor Japanese, Chinese, Russian, and American officials stretching from 1955 to today. In the middle of a comprehensive description of the topography of the Korean Peninsula, I interrupted to ask a question. What about the fact that North Korea is one of the world’s biggest recipients of food aid?

“That’s a very good question!” he said brightly. “It’s on a floodplain and they’ve been barred from getting food from any other nation except China. But even when floods happen, they’re overblown by more than 1,000%.” (North Korea does actually have advanced agronomic techniques. But more than 2 million citizens were at risk of malnutrition last year, in large part because of government policies.)

And what about the regime’s human rights abuses, its infamous labor camps?

“There’s no camps. It’s all propaganda,” he said, shaking his head. The camps are made up by “unreasonable” people who are disenchanted with the government, he explained.

Stories from supposed escapees, he said, are similar to what Nigerian migrants might say in order to be allowed into Europe. The camps, according to Muhammad, are actually a way to stop prisoners from sitting around while using up valuable state funds. Such idleness goes against the fundamentals of Juche principles. So those prisoners are sent to “reformation centers” where they learn new skills, such as farming.

He moved onto things he’d learned on trips where he and other Juche association delegates from around the world were whisked from one important function to another by the government. The literacy rate is 100% (“imagine if we had that in Nigeria, our potential”). North Korea has no unemployment (“unlike in Nigeria, where so many graduates are just left sitting at home doing nothing — it’s criminal”). And stories of Kim Jong Un’s lavish lifestyle and brutal regime as millions risk starvation are nothing unusual (“There’s no country where the leaders don’t live above the population — seriously, name me one”).

Smith, the SOAS professor, explained another part of the appeal for international Juche adherents, something she noticed during two years she spent living in the DPRK’s capital. “In Pyongyang, they get reported in the state press as if they’re big international diplomats … so it has some benefits for individuals,” she said, not unkindly.

She paused.

“But they have no influence whatsoever on African states’ policies or North Korea’s policies.”

Early on Saturday morning, the Muhammad household is bustling. The eldest daughter dashes in and out of the living room. A son is getting ready for extracurricular classes. Khadija, Muhammad’s wife, pauses underneath the portrait of the eternal leader’s late son. After he died in 2011, Muhammad had told me, a group of friends came by to offer their condolences.

I asked Khadija if she supported Juche too. (Earlier, Muhammad had nodded enthusiastically when I asked him. “One hundred percent,” he said.)

Khadija went quiet for a moment.

She wasn’t sure about joining her husband on his twice-yearly trips. “Maybe I’d [accompany] him as far as China to buy cheap fabrics and resell them here,” she eventually said with a laugh, before heading out to drop off their son.

On the sofa Muhammad’s youngest daughter, a sweet-faced nine-year-old, said she couldn’t wait to visit the country. Her father had once bought her a traditional North Korean outfit as a gift on his travels, although she wasn’t sure where it was now.

“She’s my best friend in this house. She attended the Juche African regional meeting in South Africa with me,” Muhammad said as she smiled shyly. She’d enjoyed filming the meetings on her iPad, she said.

“Aunty,” he said, using a Nigerian term of endearment, “what was it we said during the meeting when we all held our hands together?”

At the end of the meeting, it turns out, the several hundred participants had all stood up and chanted: “Vi-va Africa! Vi-va North Korea!”

Muhammad grinned at the memory. “That was a good trip,” he said.