I left therapy and saw that Claire had called.

“Can you meet me at Pain Quotidien?” she asked. “I’m in hell. I’m dying.”

“Of course,” I said.

When I got there, she was crying in the corner over an almond Danish.

“I really felt like me and Trent had a connection,” she said. “I really felt like with this whole polyamory bit I would have enough going on to keep everything under control. Like I wouldn’t get too attached or too crazy about any single one of them. Now that’s all gone tits up.”

“Which one was Trent?” I asked.

“The old one with the ponytail.”

“Fuck him,” I said. “What an idiot. You can do better. You know who else was an old guy with a ponytail? This creepy guy who used to come sit in the library for twelve hours a day. He wasn’t homeless, he had really nice sneakers, but he would just watch all the undergrad girls all day. At first I felt bad for him, because he was old and would sometimes bring soup and there is nothing sadder than an older man eating soup alone. But then one day he was caught in the women’s bathroom. He had been hiding there for hours. His name was Ron. So this guy, Trent or whatever, is basically named Ron. Basically he is a seventy-year-old man with a ponytail named Ron who lurks in women’s bathrooms hoping to catch a sniff of them. Whenever you think he is great, just call him Ron in your head.”

I thought I had done a pretty good job. But Claire just cried harder.

“That makes it even worse. That someone like him could reject me.”

“He’s not rejecting you,” I said.

“Yes, he is,” she said. “His wife said she just isn’t comfortable with the arrangement.”

“So then it’s not even his fault. He isn’t choosing to reject you.”

I wondered how gross dudes like Trent scored both a wife and a woman like Claire.

“Yes, but he didn’t even stand up to her,” she said.

No one really wanted satiety. It was the prospect of satiety — the excitement around the notion that we could ever be satisfied — that kept us going.

I wanted to be like, Look, this is what you get when you fuck a guy with a wife. This is what the polyamory people are like. You are never going to get to have the whole person. But I kept my mouth shut. Who was I to say anything? I’d just fucked a guy with a girlfriend on a public floor and wanted him to declare his undying love.

“How did the garters go?” she asked, as though reading my mind.

“Horrific,” I said. “I’m giving up men for a while.”

“No! But I adore this side of you! You were just getting started!”

“I’m just too crazy.”

“It’s that bloody group that got in your head, isn’t it? Ah well, I guess I’m on my own again to rummage through the cocks. Trent is dead to me, but at least David is more attentive now than ever,” she said.

“So pack it all into David. He’s younger and hotter anyway.”

“No, it’s too dodgy with him. He’s too hot. I might become too dependent. I need a buffer.”

“What about the guy from Best Buy? The really built one.”

“It’s not enough,” she said. “He was number three, remember? I need a new two. Or he can move up to two but I still need a new three. I have to have three.”

Seeing Claire’s insanity made me realize I was probably doing the right thing by being back in group. She could have a harem of a thousand studs, but the truth was there would never be enough to fill her need for attention — for devotion. That hole was bottomless. It was never-ending. She wanted their devotion, but should one of them — even one of the ones she liked most, like David — want her to commit, it would be over instantly. If he became obsessed with her, really fell in love, asked her to move in, she would grow tired of him in about a month. Maybe even less than a month. When I looked at Claire I saw that there was no human who could do that for us. Fill the hole. That was the sad part of Sappho’s spaces. Where there had been something beautiful there before, now they were blank. Time erased all. That was the part nobody could handle. Some people tried to shove things in them: their own narratives, biographical crap. I was pretending that nothing had ever been there in the first place, so that I wouldn’t feel the hurt of its absence. I wanted to be immune to time, the pain of it. But pretending didn’t make it so. Everything dissolved. No one really wanted satiety. It was the prospect of satiety — the excitement around the notion that we could ever be satisfied — that kept us going. But if you were ever actually satisfied it wouldn’t be satisfaction. You would just get hungry for something else. The only way to maybe have satisfaction would be to accept the nothingness and not try to put anyone else in it.

Around midnight, somehow, I found myself back out again on the rocks. It was chilly and I didn’t bring a sweater. I looked around, and then, feeling embarrassed, I stopped. It was obvious Theo wasn’t there, but I kept imagining that he was — or that he was deeper in the waves, farther out, watching me looking for him, laughing. I pretended to myself that I had come out to the rocks simply because I had wanted to be near the ocean.

But I was disappointed.

I turned to go home.

“Lucy,” said a voice.

It was Theo. Had he been hiding behind a rock? This kid was confusing. When I felt him watching me from far away, maybe was he watching me from much closer? He sort of bobbed a few feet away.

“You’re back,” I said cheerfully, but casual. I did not ask where he had been.

“I’m back,” he said. “How have the dates been treating you?”

“Disgusting,” I said.

“Ah, too bad.”

“Each its own little death.”

“Funny,” he said. “You’re like a little death.”

“What?” I asked.

“You are. You’re . . . gloomy yet charming. I like it.”

“Well, no one has said that before.”

“You’re gently death-ish. You know about death, you’re aware of it, and most people aren’t anymore. But you’re not a killer. You’re a soft darkness.”

A soft darkness.

“Yeah, I’m aware of death,” I said. “In high school I wore black lipstick and black nail polish.”

“That’s not what I mean,” he said. “It’s not manufactured. You have it in you.”

“What about you? What’s your story?” I asked.

“Oh God, I hate my story,” said Theo.

“I bet you have a great story.”

“What do you want to know, exactly?” he asked. He was treading water a little faster now. I caught a glint of his wet suit under the waves.

“Where do you live?” I asked.

“Around here,” he said.

“So cryptic,” I said. “Are you aware of death?”

He had a lot of power in not revealing too much of himself. Just that lack of willingness to disclose — that’s all it took for me to perceive rejection.

Asking that, I felt kind of creepy in a good way. He had a lot of power in not revealing too much of himself. Just that lack of willingness to disclose —that’s all it took for me to perceive rejection. So this gave me a little edge. Also, his observation about me and death could have been a bit scary if he wasn’t so matter-of-fact. I mean, he was a stranger, male, and likely stronger than me. He could easily pull me off a rock into the water and drown me. But I trusted him completely — at least in terms of my physical safety. And now that he had complimented me about my proximity to death and I had owned it, and thrown it right back at him, I felt cool. We had both decided now that death was my territory. I was the Professor of Death. Much more than a middle-aged woman who was beginning to get serious crushy feelings for a young stranger in the water.

“I know about death,” he said.

“Have you ever seen someone die?” I asked. “Like up close and one-on-one?”

“Yes,” he said. “I have watched a number of people die.”

“Scary, right? The dying process. I don’t feel scared about death but dying freaks me the fuck out.”

“I’m not scared of dying,” he said.

“You’re not?”

Now he was the professor and I was the pussy.

“I would say I’m less scared of dying than I am of life.”

Actually, I maybe agreed with him.

“I think I’m equally scared of both,” I said.

This was the truth. It felt good to say it.

“What is it about dying that scares you the most? Are you afraid of having regrets?”

“No,” I said. “I think it’s literally the physical process. Like, the suffocation. I’m so scared to be suffocating and panicking. I get panicked even when I go to the dentist. I am not good with discomfort. So I think I’m more scared of the discomfort — my own fear around it — than anything else.”

“It might be scary for a moment,” he said. “Maybe for a few minutes. But then, from what I’ve seen, you are very free.”

“Maybe,” I said. “But it’s the fear before the freedom that I’m scared of. If I could just go to sleep — just like that, go to sleep and never wake up — I would do that anytime. I would do it tonight. But I’m scared to be conscious while it’s happening.”

“I had that feeling about you. That you would be happy to just go to sleep.”

“Why? Because I’m so boring?”

“Not at all,” he said. “The opposite. But I can feel you’ve suffered.”

He was so dramatic.

“Yeah, well, life is the dumbest,” I said, standing up.

“I’ve suffered too,” he said. “I’ve been sick.”

This piqued my interest.

“Yeah?”

“Yes. I have stomach problems, terrible stomach cramps. Problems with my bowel. I don’t know why I’m telling you this.”

The word bowel made me giggle.

“What kind of problems?” I said. “Like you can’t go or you go too much?”

“Both,” he said. “It depends on the day.”

“I’m sorry I’m laughing. I know it’s not funny. But it’s weird talking about this with a stranger.”

“We all do it, you know.”

“I know. Have you ever accidentally gone in your wet suit?”

Now I was laughing so hard that tears formed in the corners of my eyes. He was grinning and treading water.

“That’s privileged information,” he said. “I feel like we’re not intimate enough to go that far.”

“Ah, okay, I understand. Good that you have your limits,” I said.

“I don’t, it’s just — we would need to be more close for me to disclose something like that,” he said, smirking.

“What would be more close?”

“I don’t know,” he said. “Like if I had touched you before or something.”

“That’s privileged information,” he said. “I feel like we’re not intimate enough to go that far.”

I felt surprised. I don’t know why I am always surprised when a man is attracted to me. Maybe because he was so beautiful and young. But I guess it made sense. Why else was he hanging around these rocks?

“Do you want to touch me?” I asked.

“Yes,” he said.

“Where do you want to touch me?” I said coyly.

He swam over to the edge of my rock. I suddenly felt nervous.

“Hmmmmm,” he said. “Would you let me touch your ankle?”

“My ankle?” I laughed.

“Yeah, your ankle.”

“Okay,” I said. “You can touch my ankle.”

He ceremoniously lifted one hand, wiggled his fingers like a pianist, and gave my calf a little squeeze. I laughed. Then, he lightly cupped my ankle and massaged it gently, looking up at me. I stopped laughing. Slowly, he ran two fingers up and down the middle of my foot bone. He pressed each of the toes, one by one, and made his way around to the back where he gently massaged my Achilles tendon.

“You have such cute ankles,” he said. When he was done massaging he sort of patted the top of my foot like a child’s head.

Then he hugged my calf with his hand and head. It was weird as hell but it felt so good.

“No,” he said. “I’ve never shit in a wet suit.” ●

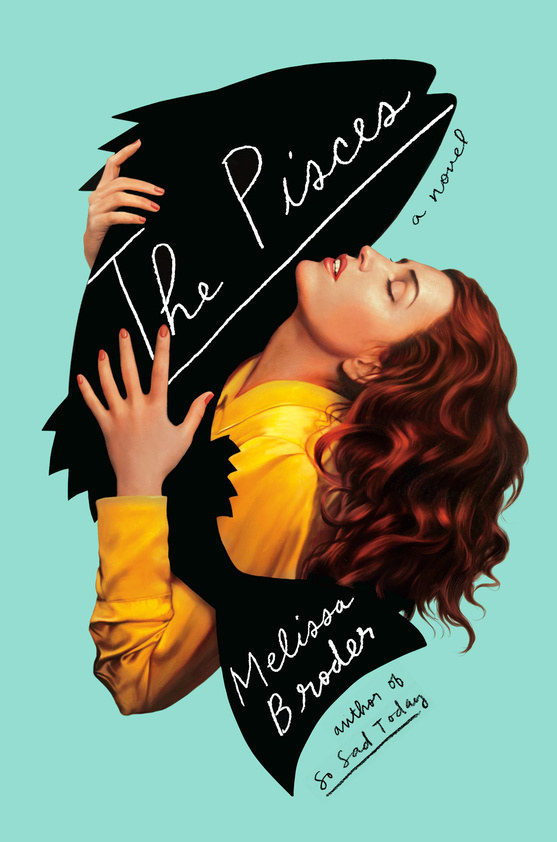

Illustrations by Laura Breiling for BuzzFeed News.

Excerpt adapted from THE PISCES: A Novel. Copyright © 2018 by Melissa Broder. Published by Hogarth, an imprint of Crown Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.

Melissa Broder is the author of the essay collection So Sad Today and four poetry collections, including Last Sext. Her poetry has appeared in POETRY, The Iowa Review, Tin House, Guernica, and she is the recipient of a Pushcart Prize. She writes the "So Sad Today" column at Vice, the astrology column for Lenny Letter, and the "Beauty and Death" column on Elle.com. She lives in Los Angeles.