MANILA — Dalisay dela Cruz was drifting off to sleep when she heard the shouts of police.

From her tiny concrete home in a Manila slum, the slight 75-year-old grandmother heard officers bang on each of her neighbors’ doors, ordering them to report immediately to the nearby government office. Staying silent, she peered through a small hole in the wooden barrier that separates her one-room home from that of her grandson.

She heard the police tromp inside his house.

She heard her grandson call out — a strangled cry for mercy.

Then she heard four gunshots, and finally, silence.

She later found out that her grandson, 29-year-old Noel Navarro, had tried to follow his 4-year-old daughter out of the house when a Manila Police District officer grabbed him by the collar and forced him back inside. It was there the officer shot him, she said, three times in the chest and once in the head.

Navarro was one of dozens of men and women in the Philippines being killed each night as part of President Rodrigo Duterte’s crackdown on alleged drug users and dealers. The total death toll, including police and vigilante killings, stands at nearly 5,600 since the crackdown was launched in July. Tens of thousands more have been arrested, often landing in overcrowded prisons. The campaign, which has primarily targeted low-level drug users and dealers, has been met with wide criticism from international organizations and human rights groups who say the government is all but encouraging extrajudicial killing.

“Do your duty, and if in the process, you kill 1,000 persons because you were doing your duty, I will protect you,” Duterte told police officers at the start of the campaign in July.

The police report on Navarro says he was killed after pulling a gun out of his waistband and firing at police. His family says he could barely afford to buy rice, let alone a firearm.

The truth about Navarro’s death, and hundreds of others across the country, may never be known definitively. Police say nearly 2,000 people have been killed in police busts alone in a little less than five months. Not a single officer is set to be tried in court over the killings, and no internal police investigation has yet revealed any wrongdoing. Police contend that officers acted in self-defense in nearly every single deadly incident.

Duterte is perhaps the most brutal leader to sweep to power in this year’s global populist wave, and his bloody campaign against drug users and dealers remains overwhelmingly popular in his country, even as the US and other Western governments have criticized its violence. He won election in a landslide earlier this year after vowing to kill 100,000 criminals and feed their bodies to fish in Manila Bay.

On the surface, the relationship between Duterte and the Obama administration has been strained, though the Philippines remains one of the largest recipients of US aid, including for its much criticized police force. The US president scrapped a meeting with Duterte this fall after Duterte called him a “son of a whore,” and the State Department has expressed worry about reports of extrajudicial killings.

“We’re very concerned — deeply concerned, I would say — about reports of extrajudicial killings of individuals suspected to have been involved in drug activity in the Philippines,” a US State Department spokesman said in August.

But a BuzzFeed News investigation has found that despite those statements of concern, the US continued to train and provide equipment to police units on the front lines of the anti-drug campaign. The State Department sent millions of dollars in aid to programs for police departments across the country even as the death toll from the drug campaign climbed by hundreds each month, according to government documents as well as current and former US and Philippine officials. Critics say this raises questions as to whether the State Department violated a US law that forbids aid dollars from benefiting police units engaged in gross human rights violations like extrajudicial killings.

“It is a flawed policy that makes a mockery of the rule of law,” Senator Patrick Leahy of Vermont told BuzzFeed News, saying he was “very concerned” about US police aid in the country.

Julia Mason, a spokeswoman for the State Department, which requested Congressional approval for $9 million in aid for its narcotics control and law enforcement programs in the Philippines for 2016, said department funds are no longer being used for counternarcotics training. But she said other programs benefiting the Philippine National Police (PNP) remained intact.

The State Department does not contest that US aid programs benefit the PNP, but Mason said units found to be engaging in extrajudicial killings do not receive US assistance.

But BuzzFeed News found that officers at police stations receiving support from the US have played a central role in Duterte’s bloody campaign. By comparing Philippine police data with internal State Department records, it is clear that many of the stations — especially those in the capital city of Manila — are collectively responsible for hundreds of deaths, including that of Navarro.

PNP officials said police are not involved in extrajudicial killings and only use deadly force in self-defense.

Mason said US training programs have been refocused onto issues including rule of law, maritime security, drug treatment, and human rights since the start of the drug war. Every Philippine police official who spoke to BuzzFeed News said, however, that there had been no substantial changes to training programs, including counternarcotics training, a description echoed by other State Department officials.

“The training programs are on a yearly schedule, and they’ve been proceeding as normal with no changes,” Police Chief Superintendent John Sosito, who oversees police training programs across the Philippines, told BuzzFeed News earlier this month. “In fact we had one here just this morning — a tactical command course.”

Civil society groups worry that the situation in the Philippines will only get worse after President-elect Donald Trump takes office, not least because he has expressed little interest in human rights issues. Duterte himself warmed immediately to Trump after his election victory, quipping, “We both curse at the smallest of reasons. We are alike.” Last month Duterte appointed the real estate tycoon behind Trump Tower Manila to be a trade envoy to the US.

Duterte has repeatedly dared Washington to withdraw aid and suggested he may end the alliance with the US in favor of China. The Obama administration’s response has been far more muted.

BuzzFeed News obtained a State Department list of more than 200 police stations and departments in nearly every part of the country that benefited from US narcotics control and law enforcement aid programs during the fiscal year that ended in September. That list also includes hundreds of Philippine police units benefiting from other types of aid programs — including maritime security, counter-terrorism, and law enforcement training, as well as programs run by USAID.

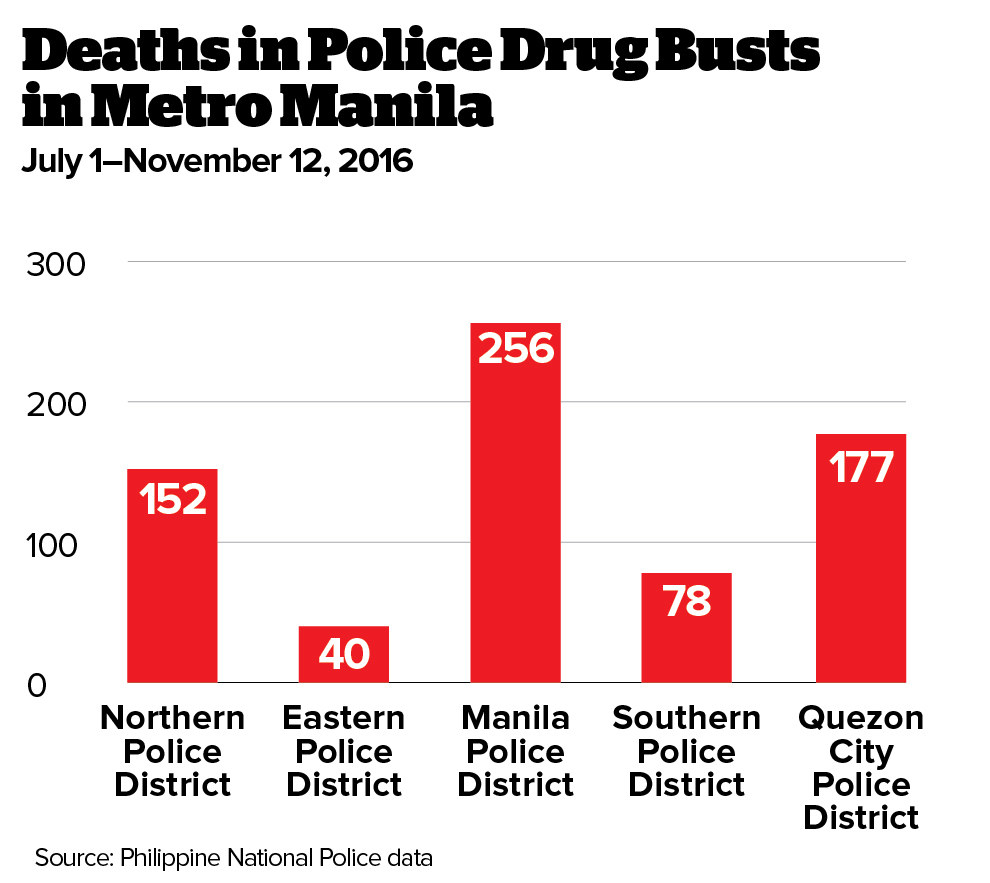

Among the units that received training or equipment, seven are located in metro Manila — the heart of the drug war. Nearly 40% of those killed in police drug busts since July were shot in metro Manila, police records show.

That includes the Manila Police District, whose officers gunned down Navarro and killed at least 255 others, and three stations in the northern Manila district of Quezon City, whose police department has killed 177 people since the drug war started in July, according to police records seen by BuzzFeed News.

Mason, asked whether there was any concern that those deaths might be extrajudicial killings, said detailed circumstances for many of them were unavailable. She added that the Philippines government should conduct a “thorough and transparent investigation” into each death.

The Southern and Eastern police districts in metro Manila, responsible for dozens more deaths in the drug campaign, also benefited from US programs. Presented with a set of police station names from the list, the State Department repeatedly declined to confirm or deny how many and which stations benefited from the aid programs.

The US is forbidden from sending aid dollars to any police or military units or personnel suspected of “gross violations of human rights,” under a statute called the Leahy Law, named after the senator who introduced it in 1997. It is central to the question of whether the State Department acted appropriately in its decision to continue aid programs to the PNP. Mason said the department is confident that aid programs are fully compliant with the law.

But several PNP officials told BuzzFeed News that US counternarcotics aid had directly benefited Duterte’s bloody campaign by training officers on the front lines and providing technology and expertise.

Members of Congress including Leahy and human rights groups have repeatedly called for the US government to cut off police aid or redirect it to treatment or rehabilitation programs for drug users.

"They took him. He was at work."

The State Department’s reluctance to cut aid underscores a newly complex relationship between the US and the Philippines, which was seen as a stalwart ally in the Obama administration’s Asia pivot strategy. Last year the US set aside more than $120 million in aid to the country’s armed forces — the largest amount in more than a decade, the ambassador to the US said in April — in the face of a Chinese military buildup in the disputed waters of the South China Sea.

The election of Duterte, a firebrand who commentators called the Donald Trump of the East, threw that relationship into turmoil. Washington has long valued the Philippines, one of the most pro-American countries in the world, as a bulwark of democracy as other countries in southeast Asia swing toward authoritarianism. But it is democratically elected Duterte, a populist who swept to power by tapping into the public’s fears of crime and economic insecurities, who rights groups say has brought on a human rights catastrophe.

US officials familiar with the Philippines said the State Department initially adopted a “wait and see” approach in light of the long-standing relationship, even as Duterte pledged to protect officers from prosecution over extrajudicial killings. But in nearly five months, there is no evidence that the pace of killing has slowed.

“We told them in August, you have to stop this now. Members of Congress were telling them, end this now,” said Michael Collins, deputy director of the Drug Policy Alliance. “The question is, have US taxpayer dollars gone into the hands of people doing extrajudicial killings?”

“That to me is a tragedy,” he added. “There was an opportunity to take a firm stand early on.”

Jay-R Derder’s family had suspected something was wrong when he didn’t come home from work earlier this month. They spent the afternoon searching for him with no luck, said his great-aunt Edith Bebiano. He had struggled with meth addiction, she said, but tried to quit months earlier out of fear the police would find him.

The police caught up with him that day, said a local government representative who asked not to be named.

“They took him,” the local official said. “He was at work.”

By nightfall, Derder’s body lay sprawled on a street in Manila, and under the glare of police spotlights and camera flashes, the long smear of blood beneath his head looked as thick and red as paint. Police prevented his family and a group of curious neighborhood schoolkids from approaching the crime scene, so Derder’s mother didn’t realize it was her son lying on the pavement until a news photographer showed her a picture of the crime scene. Her knees buckled.

“It’s him!” she cried.

The crowd let out a collective gasp and the schoolkids mobbed the photographer.

The next morning, much of the local press in the Philippines reported the police version of Derder’s death: He was a suspected drug pusher and robber who fled when officers approached him, then turned around and opened fire when he was cornered.

The State Department relies heavily on these kinds of online news reports in determining whether police units committed gross human rights violations, current and former department officials said. But in the absence of independent investigations, it is nearly impossible to tell from English language online information alone which police units are responsible for extrajudicial killings.

Police do not put statistics or incident reports directly online, and Mason said officials do not consult the PNP’s public incident reports or police logs when determining whether aid recipients have engaged in extrajudicial killings. BuzzFeed News was able to obtain some incident reports by walking into a police station and asking a public information officer.

Two former State Department officials said that because the US runs thousands of aid programs every year with foreign law enforcement agencies, officials have only a few minutes to work out if each unit or person is suspected of wrongdoing. In practice, that amounts to a quick internet search on a government search engine as well as a search of classified records. Mason contested this description, describing the process as “rigorous” and saying multiple government sections and agencies are involved.

The two former officials familiar with the vetting process said it was too cursory, and vulnerable to political pressure.

Daniel Mahanty, who once oversaw global implementation of the Leahy Law at the State Department, said vetting of police and military units and personnel is one of the last steps in approving aid, meaning there is tremendous pressure not to derail the process.

"The question is, have US taxpayer dollars gone into the hands of people doing extrajudicial killings?"

“It becomes a big political mess if you deny somebody [aid],” he said. “When you do discover information, there is pressure to clear the name.”

“We spend so much money on law enforcement and military training — this is the main instrument of diplomacy at this point, which is a scandal in and of itself,” he added. “It’s the primary means of getting goodwill, and all of a sudden you can’t do that because their hands are dirty. It’s a lot of political pressure.”

Mason said the State Department doesn’t deviate from the standard set by the Leahy Law. “The Leahy process is US law and standard practice; it is not vulnerable to political pressure from international partners or beneficiaries,” she said.

The document listing police units says the State Department vetted 9,988 people in the Philippines last year and denied training to about 1%. State Department officials confirmed the rate had not changed since July. Police officials in Manila told BuzzFeed News the US rarely turned down the candidates for training they suggested — often rank-and-file officers who work on the counternarcotics teams involved in drug busts.

Chief Superintendent Oscar Albayalde, director of the National Capital Region Police Office, which encompasses all five police districts in metro Manila, said he felt he maintained near complete control over which of his officers receive US training.

“As far as I know, they have never rejected anyone,” Albayalde said of his department.

Albayalde, who had himself flown to a training program in Maryland earlier this year, said US experts, often from the Drug Enforcement Administration, ran courses explaining how to disrupt drug supply and demand, bust local and international drug networks using intelligence, and analyze the financial underpinnings of the drug trade.

“They teach the fundamentals — what to look for and how to develop a case, how to build up intelligence,” he said. “It’s really very important to the anti-drug campaign. We have local training also, but it’s different when you get experience from a foreign counterpart.”

State Department officials say counternarcotics training primarily targeted international drug trafficking rings that could affect the US. But several police officials in the Philippines told BuzzFeed News that US training has been indispensable to Duterte’s bloody war against drugs.

Part of the budget also goes to supplying units with equipment — including state-of-the-art computers, protective gear like helmets, equipment for forensic analysis and bomb detection, and cameras for surveillance.

“It makes our investigations process proficient and more experienced,” Albayalde said. “The US has the same goal as us — getting rid of the supply of drugs.”

Duterte has vowed to kill 3 million suspected addicts, about 3% of the country’s population — a rate one senior police official said he saw as an approximate target for his own jurisdiction, though officials said there are no explicit quotas for arrests or deaths.

The police officials said in interviews that every police unit in the country was expected to comply with Duterte’s anti-drug campaign. In August, 22 police executives were sacked for “unsatisfactory performances” in meeting targets. Each police station in Manila has a counternarcotics division that works with the Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency to carry out sting operations on suspected drug users and dealers.

The dollar value of US aid is a small percentage of the total budget of the PNP — but officers said better technology and operational expertise from the US was invaluable in carrying out the anti-drug campaign.

“Of course it helps the drug war,” Sosito said. “They help us with gathering intelligence and interrogations — their knowledge in this matter helps our men become better officers.”

Sosito said there had been 90 US training sessions in the Philippines since the drug war began in July. “I don’t want to speculate, but I think it will continue,” he said, adding that he had heard nothing about the US or any other country pulling back from working with the PNP. Mason, the State Department spokeswoman, said the number of trainings that had been conducted is "not available at this time."

In a letter this month, Senator Ben Cardin of Maryland renewed a call for the US to repurpose or restrict aid to the PNP.

“I strongly believe," he wrote, "that a failure to apply the appropriate conditions, constraints and oversight on our assistance to the Philippines will both undermine the United States' commitment to human rights in its foreign policy and will, in effect, endorse these actions of the Duterte government."

The PNP, however, sees it differently.

“It’s a very good relationship between them and us,” Albayalde said. “It’s not affected by politics.”