YANGON, Myanmar — Harry Myo Lin’s problems started with a photo on Facebook.

The picture showed Harry, who is Muslim, posing with a female friend who is Buddhist. Somehow, an account belonging to a Buddhist nationalist group found it and reposted it with a caption that would put a target on Harry’s back.

It claimed that Harry, a soft-spoken 26-year-old who runs a nonprofit that works to promote religious tolerance, had “seduced” the woman and was converting her to Islam.

“They wrote it like it was a news story — like, here is this Muslim guy and the Buddhist girl he is trying to convert and bring to the beach,” said Harry. “It’s easy to say it wasn’t calling for violence — but when people share it, there were comments saying, ‘Muslims like him should be killed.’”

To Harry, it was an obvious threat. The notion that Muslims are seeking to take over Myanmar by having too many children and converting innocent Buddhists is central to Burmese nationalist propaganda, which has been circulating for many years. The threat to Muslims like Harry also comes at a time when Myanmar is fighting a political battle over what constitutes fake news and hate speech on social media, an issue that is upending the lives of Muslim minorities and has led to arrests, state surveillance, and bloodshed.

The post was quickly shared thousands of times — often with comments calling for death or violence to Harry. People began contacting his Buddhist friend and calling up her parents, threatening to harm her if she didn’t stop seeing him.

Harry decided to deactivate his Facebook profile for a month and assumed it would blow over.

But as time passed, the same kind of fake postings and threats via phone and text became more common. He said many of the hundreds of fake accounts that would post messages and comments about him had no photos or real personas, and sometimes dozens of texts from different numbers would threaten violence if he appeared in public.

“I don’t post anything controversial anymore,” he said. “I just want to work — I’m afraid I may not be able to.”

The problem has gotten worse in recent years as government officials and politicians use fake news to advance their domestic political goals and stoke nationalism. How the government, led by Nobel Peace Prize winner Aung San Suu Kyi, handles the growing problem of hate speech is seen by many as a bellwether for increasingly tense relations between the Buddhist majority and Muslim minority.

The question of fabricated news and speech inciting violence is particularly urgent for Rohingya Muslims, who have been targeted in a campaign of military-backed violence that has displaced tens of thousands and left villages burned to the ground. Rohingya advocates say anti-Muslim sentiment drummed up by extremists on social media has been critical in generating popular antipathy for the group, exacerbating a long-standing public animus against them.

More than 140,000 people have been displaced in the western Rakhine state and dozens killed in communal violence after a Buddhist woman was gang-raped and murdered by Muslim men in 2012. Five years later, many say they worry the growing vitriol toward Muslims on social media could herald more trouble in real life.

In January the government accused Rohingya activists of posting fabricated photographs and reports, which officials said damaged the country’s international image. A month before, the Daily Mail had published and then taken down an article in which it erroneously described a video from Cambodia as one that showed a Burmese soldier tormenting a Rohingya toddler with a taser. The office of Aung San Suu Kyi, the state counselor, quickly responded, labeling the article a fabrication and chastising a host of international media outlets for spreading false information about the Rohingya issue.

In 2015, Aung San Suu Kyi won a landslide victory in the country’s first openly contested elections in 25 years. A former political prisoner and an icon of the country’s democracy movement, Aung San Suu Kyi remains overwhelmingly popular — and is seen as the de facto leader — though her power is restrained by the military, which controls several key ministries and 25% of seats in parliament. Her National League for Democracy (NLD) party has faced criticism for failing to run a single Muslim candidate in the most recent election.

On the question of fake news, statements from Aung San Suu Kyi’s office sometimes echo pronouncements by the government of ex-generals that came before her. Former president Thein Sein called reports of ethnic cleansing a “smear campaign against the government” in 2013.

Pro-Rohingya groups as well as Buddhist nationalist groups in the country regularly spread fictitious or defamatory news online, but it is Muslims who are inordinately targeted. Research by NGOs including the Myanmar ICT for Development Organization (MIDO) and the Institute for War and Peace Reporting found that the overwhelming majority of hate speech and other attacks on Facebook, the most popular social media outlet in the country by far, is directed at Muslims.

The breakneck growth in internet users in Myanmar has compounded the problem of fake news, especially because many new users of social media lack the knowledge and skills to tell real news apart from fake, according to tech accelerator Phandeeyar.

BuzzFeed News interviewed more than a dozen Myanmar Muslims, including some Rohingya Muslims, who have strong followings on Facebook, and who have been harassed, doxxed, hacked, and regularly called racial epithets. Some said they had to suspend their work, and others reported being questioned by domestic security services about made-up stories depicting them as terrorist sympathizers online.

Fears over public animosity toward Muslims reached a fever pitch in late January when Ko Ni, one of the country’s most prominent lawyers and an adviser to Aung San Suu Kyi, was assassinated, sending shock waves through reformers in the country. Ko Ni, who was a Muslim, was best known for his advocacy for constitutional reforms in the country. The constitution was written by the military, and under its wording, civilian leaders do not have the power to revise it alone.

Ko Ni was shot in the head while he was standing at a taxi stand outside the airport in Yangon. The suspected gunman was hired by former military officers, according to a press release from the office of President Htin Kyaw, but officials say his motivation is unknown. Four men suspected of working together to assassinate him stood trial in Yangon on March 17.

His friends and colleagues told BuzzFeed News that in the months leading up to his death, Ko Ni had contended with an increasingly vocal internet campaign targeting both his political work and his Muslim background.

Before he was gunned down, Ko Ni was also leading the drafting of a bill that would target hate speech and discrimination against minority groups. He advocated for causes considered controversial in Myanmar, including rewriting the constitution and granting full citizenship to ethnic minorities including Rohingya Muslims.

“There has been a campaign against Ko Ni since August,” said Myo Win, who had worked with Ko Ni and saw him regularly in the months before his death. “They would say he was a Bengali, and making us pay for Muslims, that he was not trustworthy.”

Myanmar’s government and the majority of the public do not accept the term Rohingya and refer to the people as Bengali, suggesting that they are migrants from Bangladesh regardless of how long they have lived in Myanmar. Ko Ni, however, was not a Rohingya Muslim.

“If even he can be targeted, is anybody else safe?”

On social platforms, commenters would accuse him of seeking to ruin the country and lob racial slurs at him.

Ko Ni’s daughter, Yin Nwe Khine, declined to speak with BuzzFeed News, but in an interview with Reuters last month, she said her father had been repeatedly threatened over his work. One of his associates, who asked not to be named, confirmed to BuzzFeed News that they had been followed by domestic security officials on a trip they took together.

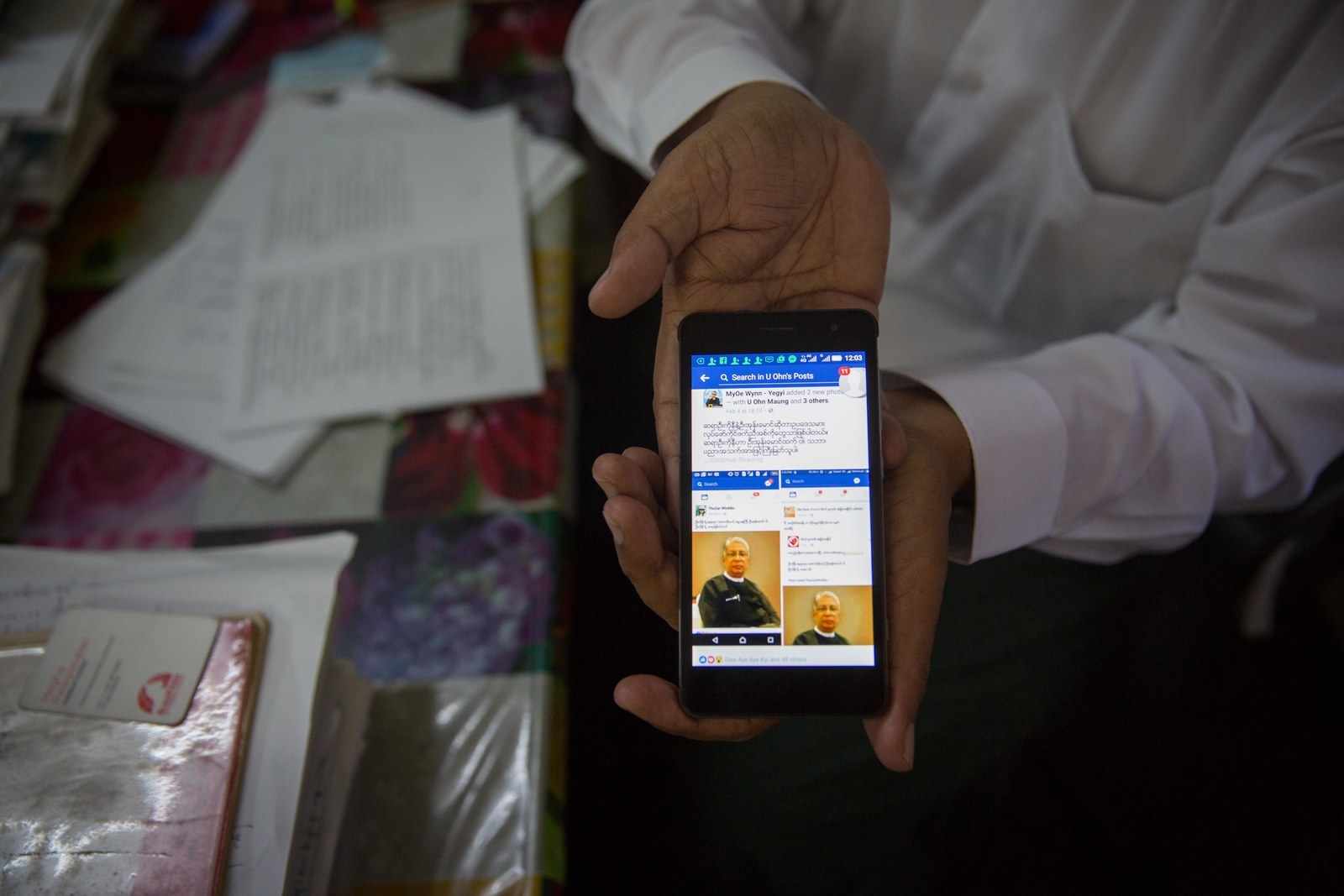

“He was targeted by a certain group of people on Facebook who just didn’t like him because of his religion and the role he was playing in government,” said Ohn Maung, a well-known legal adviser who had been close with Ko Ni since their college days.

“He used to say that he just had to do what’s right for him and keep doing his work,” he added. “But his family was worried that he would be targeted. He had no official security guards.

“Then it finally happened.”

Whatever the reasons behind Ko Ni’s assassination, it empowered extremist groups, several prominent Muslim lawyers and intellectuals told BuzzFeed News. Many Burmese Muslims said there had been an uptick in harassment by nationalist trolls following the assassination, and that they were pulling back from Facebook.

Aung San Suu Kyi has come under fire from foreign governments, international organizations, and human rights groups for failing to rebuke the military over abuses in Rakhine state. Though she has promised to investigate UN reports of atrocities against the Rohingya, she rarely speaks to news reporters about the issue and has sometimes reacted with frustration when asked tough questions about it.

Aung San Suu Kyi maintained silence for weeks after Ko Ni’s death and did not show up at his funeral. But she later appeared at a memorial service for him, calling his death a “deep loss” for her party.

Muslims in Myanmar have begun to fear that public aversion toward the Rohingya, who are denied citizenship and considered by the government to be Bangladeshi immigrants, has morphed into a broader animosity toward all of the country's Muslims – a kind of sectarian hatred that was once considered a major taboo.

“Ko Ni was so prominent, and he was close to the NLD,” said Wai Wai Nu, a Rohingya activist in her mid-twenties. “If even he can be targeted, is anybody else safe?”

For Wai Wai Nu, online harassment had become so routine that she shrugged it off, she said, even when nationalist accounts would message her pornographic images or doctor photos of her to make it look like she carried banners bearing separatist slogans.

Last year, nationalists harassed members of parliament whom she had hoped to work with, threatening them to stay away from her because she is a Rohingya woman. In the end, the lawmakers were scared off.

“They used my pictures with members of parliament and used it to attack them,” she said. “After that, those MPs wouldn’t speak with me anymore.”

“These people are intelligent racists,” she added. “They know who I am. When they attack, it’s coordinated.”

Robert Sann Aung, a Muslim human rights lawyer and friend of Ko Ni, is a generation older than Wai Wai Nu but expressed a similar sentiment. He also regularly received threats both online and via text message and said he did his best to ignore them.

Then, the day after Ko Ni was killed, he said he received a phone call from a number he didn’t recognize.

“You’re next,” the caller said, before hanging up.

Fake news demonizing Muslims, particularly reports spreading fears of terrorism or Islamic fundamentalism, has sometimes led to disastrous consequences. Those reports have spread like wildfire on Facebook, where Buddhist nationalist groups like Ma Ba Tha have gained prominence by building legions of followers.

That’s what happened in the region of Bago, north of Yangon, on June 23, when a Buddhist mob reportedly destroyed homes and forced dozens of villagers to flee after rumors spread online that a new building in the village was going to be a Muslim school.

Muslim groups say police rarely take action when there is violence against Muslims, but feel pressure to act when Buddhist nationalist groups incite public anger.

“Facebook has no way to check whether this information is correct or not,” said a Rohingya activist who asked not to be named. “Local authorities have the responsibility.”

Activists say it’s much harder to convince police to take action when it comes to threats against minority groups.

The government is in the midst of developing a law meant to target online hate speech in the country, and Aung San Suu Kyi’s NLD has repeatedly criticized hate speech, saying it harms national unity. But many fear that the law will simply be used to censor speech that is critical of the government because of its broad wording.

A recent draft of the law seen by BuzzFeed News gives extensive powers to the Ministry of Religious Affairs to determine what constitutes hate speech, leading to fears among religious rights groups that the law could be used to target critical speech. The ministry is headed by a former military officer from Thein Sein’s party and has faced criticism from religious minority groups for only protecting the interests of Buddhists.

Myo Win, whose NGO has consulted with the government on the drafting of the law, said it should define hate speech in concrete terms to ensure its provisions would not be abused. He said he felt the law did not offer sufficient protection for discrimination against minority groups, and he didn’t trust that it would actually protect Muslims.

Ko Ni had been a vocal advocate for the law, and its proposal came about after a public outcry over the damaging impacts of hate speech online. Violators of the law would be fined or sentenced to years in prison.

Countries like Germany have proposed levying major fines on social media networks if they fail to police hate speech. But in Myanmar, which only a few years ago had draconian limits on critical speech and thousands of political prisoners, any law that curbs expression is controversial.

The Muslims who spoke to BuzzFeed News said they didn’t believe government officials would help them even if they reported their cases. Many of them said they had regularly reported abusive comments to Facebook, but few of the posts were taken down.

MIDO, which regularly monitors Burmese hate speech on Facebook as part of a research project with Oxford University, found that only 10% of the postings it reported according to its own definition of hate speech were eventually taken down by Facebook. The reporting mechanism is clunky, and the process is opaque, said MIDO’s Htaike Htaike Aung.

In a statement to BuzzFeed News, Clare Wareing, a spokeswoman for Facebook, said, “Facebook is no place for the dissemination of hate speech, racism or the incitement to violence and we will remove content that violates our community standards when it is reported to us.”

Facebook determines which postings are harmful by its own metrics, outlined in part in its community standards. In countries like Germany, which have tough and explicit rules about what constitutes hate speech, the social network has worked to comply with laws. But in Myanmar, where existing laws can be ambiguous and selectively enforced, it is less obvious where Facebook’s responsibilities lie.

Wareing said Facebook works with local communities and NGOs to make clear to people how its reporting process works. Facebook has translated its community standards into Burmese and has worked with MIDO to create stickers that promote positive speech online.

Although dozens of people have faced online defamation charges under a provision in the country’s telecommunications law, most of those were cases where people criticized or made fun of Myanmar’s leaders online. Activists say it’s much harder to convince police to take action when it comes to threats against minority groups.

In an interview with BuzzFeed News, Myint Kyaw, deputy permanent secretary at the Ministry of Information, said the issue was largely the character of individuals, and not the responsibility of platforms like Facebook.

“I don’t think Facebook is responsible for this because it is just a tool,” he said. “It is directly related to the character and attitude of the users.”

Hate speech on social media, he said, is impossible to control.

Harry said he hoped Facebook would do more to address the problem. He added that Facebook did eventually take down some of the postings he complained about after he ran into one of its representatives at an event in Yangon.

He has less confidence in the police.

“I have no faith that they might be helpful,” he said.