Brent Brown had been silent for months, refusing to speak with media about the monumental collapse of his restaurant franchise — about how he had raised what some of his shareholders estimate was more than $100 million and then lost every penny of it. But now here we were, in the parking lot of V Pizza in Jacksonville, Florida, at 10:30 on a June morning, and he was as ready to talk about it all as he ever would be. Brown, a 47-year-old former high school football star, was over 6 feet tall and solidly built. His light brown hair was cropped close and clean, military style — short on top, shorter on the sides — beard trimmed tight. His eyebrows were lowered toward me, and he shook my hand firmly.

Between late 2008 and early 2016, Brown raised a fortune for a concept called Latitude 360. More like an entire block of a college town than a restaurant, each Latitude venue contained a large bowling alley, movie theater, comedy venue, smokers, video game arcade, event space, bar, full-service restaurant, and humidors for cigar smokers. The chain launched in a 46,200-square-foot former Toys ‘R’ Us about 13 miles southeast of Jacksonville and then expanded to include two additional, comparably sized locations in Pittsburgh and Indianapolis. The three venues and Latitude’s corporate office employed hundreds of people and brought in more than $18 million in total annual revenue at their peak. Latitude’s investors included NFL stars such as Atlanta Falcons wide receiver Julio Jones and Seattle Seahawks defensive end Cliff Avril; Outback Steakhouse co-founder Tim Gannon sat on Latitude’s board of directors.

But Latitude collapsed this year. The Jacksonville and Indianapolis locations closed on the same day in January; Pittsburgh closed in March. Latitude’s stock — which had gone public less than two years prior and risen as high as $3 per share — soon went to $0.

There had been hints that Latitude was experiencing trouble, but it would’ve been difficult to predict the breadth of financial chaos that followed Latitude’s demise. At least 57 lawsuits have been filed against Brown, Latitude, and corporations associated with the company. One of those lawsuits said Brown convinced an elderly couple, Tommy and Linda Tharp, to empty their 401(k) to hand Latitude a short-term loan, and then never paid it back. Another said he did the same with a Swiss investor, Karl Wadsack, who loaned him $3.5 million. Latitude’s Jacksonville and Indianapolis landlord sued the company for millions in unpaid rent. Latitude owed money to the IRS, as well as to various state agencies and contractors. While most of those lawsuits involved a failure to pay bills, others went further. Latitude’s former chief financial officer, Craig Phillips, claimed that Brown had hidden tens of millions of dollars in debt from shareholders, indicating possible securities fraud.

Beyond the lawsuits, employees claimed that their paychecks had bounced, and that they were unable to collect unemployment compensation because Latitude had failed to register its workers with state employment agencies. People close to the company — including Brown’s brother, Kyle, who was an operations manager at Latitude before being fired — pointed out that Brown had filed Chapter 13 bankruptcy in 1998, and that he lived in a modest Jacksonville home, and drove modest cars, before he started Latitude. Afterward, in 2011, he moved into a riverfront Jacksonville mansion valued at nearly $3 million and started driving luxury vehicles and wearing expensive watches. James Fonseca, a stockbroker who helped get Latitude stock listed on Wall Street markets, referred to Brown as “a mini Bernie Madoff.”

When the lawyer of a former employee alleged in a television interview that Brown had stolen money from the company, Brown stayed quiet. When Brown was subjected to dramatic stakeout interviews by Jacksonville television reporter Jenna Bourne, he only quipped about Bourne’s reporting tactics before getting into his Range Rover and speeding away. When Florida’s state attorney told Bourne that she might charge Brown with “a world of white-collar crimes” connected with the company’s extraordinary growth and abrupt demise, Brown said nothing in response.

But where others sought answers for why he’d mismanaged his company and his debts so thoroughly, he saw an alternative reality: His company may have been in trouble when Latitude’s venues closed, but it met a premature end and was forced out of business before he had the opportunity to revive it. As for allegations of fraud and wrongdoing, Brown denied everything.

“I have not been charged, the company has not been charged, and it’s not illegal to owe debt,” Brown told me. “So, the news stories literally say nothing other than there’s victims. Well, I’m a victim, too. We’re all victims. Any company that goes out of business has job losses and creditors that are owed money. That’s it. So that’s not really, to me, the story, that this company hit the wall. The story is, why couldn’t I turn the company around? And who suffered? The creditors, the employees, and the shareholders. Did they have a fair shot at getting their money back?”

Brown didn't pause for a response. It wasn’t really a question.

“There’s no fucking way they had a fair shot,” he said.

Brown was born in Omaha, Nebraska. His father, George, was a manager at department stores such as Hills and Walmart, so the family — George and his wife, Sheri, and Brent and Kyle — moved around frequently. They lived in Michigan, Maine, Illinois, Missouri, and Ohio, before landing in Pittsburgh, where they stayed until Brent and Kyle finished high school. Brown’s mom worked as a secretary when she could, and she said the family’s frequent moves “made them stronger because they had to prove themselves at every school they went to.”

That seemed clear as Brent Brown grew up. He was a star quarterback at Montour High School, northwest of Pittsburgh, and graduated from the US Naval Academy in 1991. He then moved to Jacksonville to work as an investment banker with brokerage firms until 2003, when he transitioned into buying and selling real estate for the Brownstone Group, a company he co-founded with Kyle.

One night in late 2007, Brown and a friend were at a bar. Florida’s real estate market was sinking, and they were brainstorming new business ideas. Brown and his wife had three young children, and they were often looking for places to go where their kids wouldn’t be bored and they could grab a drink or two. So-called FECs — family entertainment centers — combine restaurants with activities that both kids and adults can enjoy before or after a meal. And in 2007 and 2008, some FECs were doing very well. The preeminent FEC, Dave & Buster's — a restaurant, bar, and arcade concept franchised all over the country — had been around since 1982. Meanwhile, boutique bowling alleys such as Lucky Strike Lanes were taking off in places like Chicago and Philadelphia. Why not take these models and then add some additional attractions for adults — humidors for cigar smokers, an event space for comedy, and a movie theater for first- and second-run films. But Brown wasn’t really sold on the idea until he visited Big Al’s in a southwestern suburb of Portland.

“On a Wednesday night, I walk out and I look at the bowling facility and there’s three generations around at every lane,” Brown recalled. “The granddaughter bowls down the line, comes back, high-fives the grandma, and all of them are cheering, and I’m like, ‘Holy fuck.’ I’m getting goosebumps right now, because that’s when the lightbulb went off.”

Brown’s timing was awkward, though. He started seeking capital in 2008 — right around the time Lehman Brothers filed Chapter 11 bankruptcy and President George W. Bush was flooding cash into capital markets to keep the economy alive. “We were in the worst recession in US history,” Brown told me. “Banks were going out of business every week. No financing was available for any startup, or most companies for that matter.” But Brown had a secret weapon: a cadre of potential investors he’d amassed as a stockbroker. With individuals, Brown didn’t have to worry about the panicked state of the banking industry, or how the macroeconomy appeared to institutional experts. He could just concentrate on selling.

Since the company didn’t yet have public stock to hand out, Brown would instead solicit loans and, in some cases, promise high-interest payments in return. To people like Tommy and Linda Tharp — an elderly couple who had built a retirement nest egg on the success of a small telephone installation business, and who had been introduced to Brown when he was a stockbroker — it seemed like a perfect situation. They agreed to hand Brown $100,000 out of their retirement savings. To make the deal even more appealing, Brown offered a promissory note that the loan would be paid back in full within two years at an annual interest rate of 15%. The deal sounded so good that the Tharps later cashed out their 401(k) to hand Brown another $200,000. (Brown denied having signed a promissory note with the Tharps, but it was an exhibit in court documents.) Multiple investors have told me that they signed similar deals. John Mosimann was one of them: A former elementary school principal in Pittsburgh, he invested $80,000 of his retirement savings into a Latitude loan after Brown signed a promissory note with him that assured a 10% return. “I was trusting,” he told me.

By the end of 2008, Brown had gathered enough startup capital to lease and begin reconstruction of the former Toys ‘R’ Us location along Route 1. The first restaurant would be known as Latitude 30 — a name referring to Jacksonville’s geographical coordinates on the 30th parallel. Each new restaurant would be named after the latitude of the city where it was situated.

On the first Thursday of January 2011, Latitude 30 opened its doors for the first time. If there was any initial worry among Latitude’s investors, it dissipated. Brown’s mom, Sheri — one of Latitude’s first corporate employees — told me a line stretched around the building on that first night. Brown said the venue pulled in more than $110,000 its first weekend.

“I was so proud of him,” Sheri told me. “He brought me to this empty building, this Toys ‘R’ Us. I thought, You gotta be kidding me, what are you talking about? And when that thing opened up, it was unbelievable. Investors would come in and say, ‘Your son is absolutely our hero.’”

That success continued. Latitude’s Jacksonville location remained popular. Brown opened two more locations: Pittsburgh’s Latitude 40 in November 2012, and Indianapolis’s Latitude 39, two months after that. Each venue would draw large crowds. Brown’s brother, Kyle, remembered feeling exhilarated. For those first few months, he said, “There was always a line out the door.”

“I remember thinking, This concept’s going to work,” Kyle said. “Brent overcame a lot of hurdles to open up a business like that, and in the economy we were dealing with at that time, not too many people could have pulled it off.”

“The question is, how did he pull it off?” Kyle continued. “Was it aboveboard? Was it kosher?”

“I was obsessed,” Brown told me during one of the many conversations we’ve had about Latitude's rise and fall. “There was no point in the day when I was not thinking about this concept, talking about this concept. Everywhere I went, everyone I talked with — this was everything.”

Selling came easy for him, and even now he remained animated and evangelical about the business's early days. "I can walk in on a Saturday afternoon and I can see three generations there on a playdate, everybody having a great time,” he said. “Then I can go there later that night and see two generations on a double date. Come on, man, where are you seeing that? What brand is offering that?”

One of Latitude’s early investors, Robert Shear, told me that Brent’s fervor for Latitude was contagious. “He knows how to sell you, how to get you to like him,” Shear said. “He comes across as a man you can trust, a man you want to know — a man you want to be in business with.”

He also seemed to maintain a grounded personal life; he’d been with his wife Toni since they were in high school together. And he was deeply driven, always on the road meeting with potential shareholders and attempting to grow the business. “He worked so hard and so many long hours to raise money,” Sheri told me. “He missed his kids’ ball games, he missed his little girl’s dance recitals. He said, ‘I’m just trying to build a good future for us.’” All of this resonated with shareholders, and his background with the US Navy didn’t hurt, either. He once wrote a column for Inc. magazine titled “4 Entrepreneurial Lessons I Learned in the Naval Academy.”

Brown attracted hundreds of people to sign on with him, and to hand him tens of millions of dollars to build his company. Construction costs, totaling more than $26 million, were paid with dollars from hundreds of independent investors.

One investor Brown wishes he’d never brought on was his former neighbor, Aaron Riley.

At 6-foot-5 and more than 250 pounds, Aaron Riley had his education paid for by a football scholarship — first at Furman University in South Carolina, then at Jacksonville University, where he played defensive end and completed his bachelor’s degree in sociology and his master’s in business administration. So instead of taking out college loans, he took out loans for a car. In November 2013, at 23 years old, he bought a 2006 Aston Martin DB9 — the kind of car James Bond drives. He got it “cheap” at an estate sale, Riley said, for $90,000. His plan was to flip it and sell it for $115,000. Instead, he wound up trading it to Brent Brown.

By this time, Latitude was well on its way to being a public company. Where Brown had previously signed promissory notes with investors — in some cases personally guaranteeing loan repayments plus interest — he was now exchanging shares of his soon-to-be-public company for investment dollars. He and Riley agreed to do a stock trade for the car. Riley had seen Latitude’s popularity, and he knew that Brown was doing well enough to live in a riverfront mansion.

“All the presentations were well-done, they were raising money, he’s living in this big $3 million house, he’s got three Range Rovers, his three kids are going to [The Bolles School] — a $20,000-per-year school,” Riley said. Brown was also renting an apartment in New York City’s Tribeca neighborhood that’s currently listed at $15,900 per month. “So it looks like he’s doing really well.”

The deal sounded good to Brown, too. And Riley was, Brown told me, someone he thought he had some things in common with. They were both football players; they were both interested in business. Riley had only one real concern: He'd borrowed money to purchase the car — which he intended to flip quickly. He told Brown he wasn’t able to hold on to an expensive car loan for long. He needed to sell stock as soon as possible. It was January 2014 by that point. Brown assured him that Latitude stock would be publicly tradable within 90 days of their conversation.

Riley was in. For the Aston Martin, Brown’s holding company, Structured Holdings, would give Riley 180,000 shares of Latitude stock at a rate of 60 cents per share. Riley asked for a consulting job with Latitude, too — a $2,000-per-month gig.

March 2014 arrived and Latitude had not gone public. But Riley wasn’t panicking yet. The company was planning to go public through a reverse merger — a process by which a company like Latitude takes over an already public shell company that’s gone out of business.

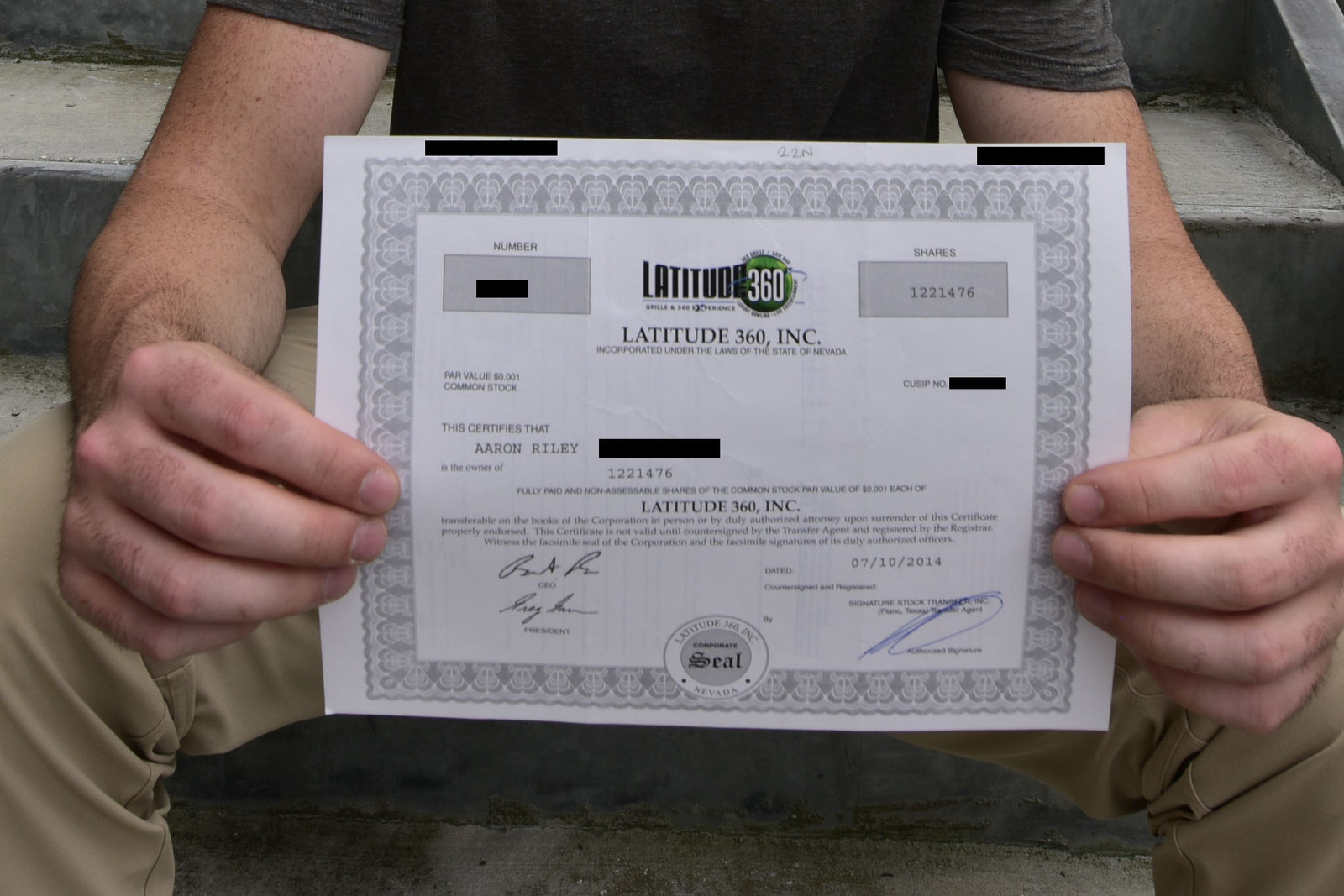

By then, Brown had renamed all the venues Latitude 360, started a Nevada holding company for the business, and identified a shell company to attach it to — Kingdom Koncrete, Inc. Kingdom’s stock was frozen at $3 per share. As soon as this became tradable as Latitude stock, someone like Riley, who owned 60-cent shares, would have the opportunity to make a fortune — quintupling their investment immediately. Riley’s $90,000 would turn into more than $500,000. He liked those odds, and he borrowed money from friends and family to buy even more Latitude stock. He deferred those $2,000-per-month paychecks, too — and took stock instead. He eventually amassed more than 1.3 million shares.

“I’m like, Holy shit, I just turned 23, I’ve got all these shares — I’m like, Oh my god, this is the real deal,” Riley told me. “I never thought I would be in this position. But that’s why they say paper millionaire: It’s not real until it’s in your bank account.”

In October 2014, Craig Phillips, Latitude’s former chief financial officer, sued Latitude to recoup shares he said he was owed, along with more than $150,000 in severance. The lawsuit wasn’t unusual; people sue their former employers all the time. But it contained serious allegations.

Phillips claimed in court documents that Latitude used all of its available cash to bring in new lenders and investors — and then never met its obligations. People who had been told that their loans would be repaid were basically ignored; their interest payments were rarely paid, and the principal amount they were owed ended up just another line item on a growing list of unsustainable debts.

Despite the investor push, Phillips said in the lawsuit that the company was “cash strapped” and had “little resources to pay for regular operational expenses including salaries and taxes.” Though Phillips was technically the CFO, he said Brown had ultimate control over all the company’s cash. The Jacksonville location was doing very well, by all accounts. But Phillips was never sure exactly how much money was coming in from the venues, or from investors. Furthermore, he didn’t know where the money was going, he said. Brown would assure vendors, suppliers, and even employees that Latitude was just days or months away from a big payday from a major investor, and that when that occurred, everyone would receive all the money they were owed — and more. This strategy kept those investors, suppliers, and employees “on a minimum cash diet,” Phillips wrote.

Latitude employees made similar claims. Kathy Marshall, former director of operations in Pittsburgh, who started with the company in May 2013 and was there until October 2014, described a kind of chaos surrounding paychecks: Employees would race to banks to try to get the last dollars out of the fast-dwindling account paying their salaries. When those checks bounced, managers would go into the restaurant’s safe and pay employees with whatever was available from cash sales.

“People’s bank accounts had closed on them,” Marshall said. “It was a hardship. You can’t just repeatedly try to cash bouncing paychecks and not expect the bank to do something.”

Phillips's lawsuit made similar allegations. It also alleged that Latitude failed to pay employee- and payroll-related tax liabilities to the IRS. Premiums for its employees’ health insurance were not being paid on time, he said, and in some cases, they weren’t being paid at all. (Brown claimed that Phillips "was in charge of paying the bills, not me.")

When Brown refused to change his ways, Phillips said in the lawsuit that he feared he’d eventually be brought up on civil and criminal charges, so he quit. Phillips wrote a letter to the company’s board of directors that was appended to the lawsuit. It said Latitude was “insolvent” — at least $20 million in debt. This went counter to documents Brent was showing shareholders.

“I cannot participate in this deception and [these] questionable practices,” Phillips’s letter read.

Riley was still receiving Latitude stock as a consultant. A friend who worked in the accounting department showed him statements indicating that Latitude was millions in debt and not paying its taxes. The friend and Riley confronted Brown, who told them he was expecting a large investment that would fund the outstanding tax debts, Riley said. Brown didn’t deny this to me. He said (and provided some documentation over email showing) that his claims about major outside investments were true: The company was expecting a big cash infusion, but several large deals — one for as much as $20 million in investment capital from a New York–based financial services company — fell through due to various disagreements with lenders, Brown said.

As months passed, Riley said he asked Brown repeatedly about outstanding debts and heard the same story — that the company was awaiting cash, and that when the cash came through, the bills would be paid off, the stock would rise, and everyone would make a ton of money, as promised.

Riley doubted Brown. He asked for the Aston Martin back, but Brown said no. “I can’t do anything right now,” Brown wrote to Riley in a text message. “I’m on lockdown personally.” Brown was still touting big deals that he was putting together for Latitude, and Riley was still holding out that he could make a return on his Latitude stock. They negotiated a compromise: Riley had purchased another Aston Martin — a black one, of slightly lesser value. Brown agreed to trade the white Aston Martin for the black one. According to Riley, Brown said he would let Riley sell 100,000 shares.

They made the car swap. But Riley was never allowed to sell shares, he told me; the shares he received from Brent were “restricted,” meaning that they couldn’t be sold until a restrictive legend was removed with permission from Brown or Greg Garson, Latitude’s president.

James Fonseca told me this was part of Brown’s strategy to make the company’s stock seem valuable. Fonseca started working with Latitude in late 2014 to act as its corporate stockbroker, and to introduce Brown to major Wall Street investors. In exchange, he said, Brown would provide him with access to Latitude’s shareholder list — a treasure trove, as Fonseca saw it, of private individuals who were eager to invest.

The relationship between Brown and Fonseca was strong, Fonseca said, until one day in late spring 2015, when they held a meeting on a rooftop of a residential property in lower Manhattan. Brown and the company’s president, Greg Garson, had brought a briefcase filled with information on a large group of Latitude’s shareholders.

“I knew what he was handing me. It was a big deal, $100 million worth of shareholders,” Fonseca said. (Brown asserts that, in all, he raised approximately $74 million for Latitude.) “At that meeting, it got weird, though.” Fonseca said he assured Brown that the shareholders would be in good hands. “I’m telling them, ‘I’m going to take in the stock, help everyone out and register it — make sure it’s tradable.’ And Garson looks at me and says, ‘That’s not what we want to do.’ He tells me he doesn’t want people to sell the stock. He doesn’t want anyone to do anything.”

In Fonseca’s interpretation of the situation, Brown had no intention of letting anyone make money off Latitude stock. And while Brown was refusing to let shareholders sell stock, Fonseca came to believe Brown was selling his own stock. "They wanted to sell for themselves," Fonseca said, "while everyone else got crushed." Though SEC filings show that Brown’s holding company had 90,469 fewer shares in February 2015 than it did in June 2014, and that Garson's company had 255,658 fewer shares, Brown denied selling stock or disallowing anyone from selling stock. “I repeat under oath, cross my heart, we did not sell any public stock, period," he said in an email. "Do you not think that the auditors would see the change in shares? The board? The SEC?" Instead, he said, he gave shares away during this period. (Garson declined to speak with me for this story.)

Latitude investor Garry Aujla invested more than $1 million personally into Latitude. He was not present at the meeting with Fonseca, but he told me that his shares were restricted, and that both Garson and Brown told investors that they would not be able to sell. “These guys, they basically stiff-armed all the shareholders and said, ‘No, we don’t have time to lift the legends off the certificates so they can be tradable in the actual market,’” he told me.

Garry’s father, Shawn Aujla, also invested as much as $1 million into Latitude. He told me that Garson told him point-blank that he was afraid of a mass Latitude stock sell-off. “Everyone is getting restricted [stock],” Shawn recalled Garson saying. “If we didn’t restrict them, then people are selling them and the stock will go down.” Furthermore, Shawn was wondering where money invested into Latitude had gone. As an example, he noted the company’s failure to pay rent or payroll taxes. “Why would you deduct employee payroll taxes from their paychecks, from their wages, and then not pay the government?” he asked. “Where does it go?

Craig Phillips’s attorney, Mike Rubin, had a theory. He told me that Brown was using the company “as his own personal piggy bank. He was making huge expenditures at a time when cash flow was negative and the company wasn’t able to pay its bills.”

“This is the classic Ponzi scheme kind of setup,” Rubin continued. “He would go to new investors and get a new infusion of investment capital, and with that capital, he would spend it on himself personally and he would take the other part of that and take care of old debt to disgruntled investors and vendors of the company who weren’t getting paid — and you can only do that for so long.”

Brown vehemently denied Rubin’s allegations. “We are an audited company,” Brown wrote in an email to me. “How could this happen? The answer is absolutely not. Rubin knows this. He has all of our financials.”

In the fall of 2013, when Latitude was working toward a public offering, Brown gave a presentation to shareholders about the state of the company showing that Latitude was losing money but that new investments, and impending expansions to suburbs of Albany, Dallas, Boston, and Chicago would triple its net sales to more than $40 million per year by the end of 2014. And the company would only grow from there. Latitude’s future looked bright. On the last page of that presentation, Latitude showed that it had about $12 million in current total liabilities — debt to shareholders, leaseholders, and other creditors — perhaps not an unreasonable amount for a company that had just built three giant entertainment complexes and was planning to build more.

When Latitude released its financial documents in the summer of 2015, however, it showed that these figures were egregiously wrong. Net sales were about $20 million — not $40 million. Brown chalks that up to deals that fell through to bring additional Latitude locations. But the accounting problems didn’t end there. The company’s liabilities were $88.4 million — more than seven times what they allegedly were in fall 2013. Latitude was in default on nearly $21 million in lease payments, and it owed about $5.6 million in unpaid payroll taxes. Plus, no additional venues had opened. The 2013 shareholder presentation proved to be an unrealized fantasy.

Garry Aujla had been an investor in Latitude since 2010. When he saw those 2015 financial figures, he told me he sat up and said, “Hey, what the hell is going on here?” After that, he thought the whole thing started to unravel.

In September 2015, EPR Properties, Latitude’s landlord in Jacksonville and Indianapolis, filed a $5.8 million lawsuit against Latitude for failure to pay rent on the two locations. Jordan Cole was operations manager at Latitude’s Jacksonville and Pittsburgh locations at the time. After the EPR lawsuit hit local media, he said, Brown showed up at the Pittsburgh venue to give a motivational speech. It lasted about 30 seconds, Cole said, and then Brown left the building. “The only thing anyone talked about after he left that day was his $12,000 watch that he had on his wrist when he looked at everyone and said, ‘I’m gonna pay payroll,’” Cole said. “Everyone was saying, ‘Why don’t you sell that watch?’”

Riley wasn’t listening to Brown’s assurances either. He couldn’t sell stock, he said, and the company was in a free fall. He again asked for the black Aston Martin back. “He just totally, he loses it,” Riley told me. “He’s like, ‘No, you’re not getting this car back.’ I was like, ‘If you don’t give me this car back, you’re going to have some serious problems, because I know what’s going on now.’ He didn’t say anything, and I got up and walked out.”

Something snapped in Riley. He contacted investigators and detectives and representatives of all sorts of state and federal agencies. He began sending emails to shareholders, telling them that Brown was a crook, and that Latitude was about to implode.

He also contacted Jenna Bourne, a television reporter with Action News Jax, who began looking into the business. Bourne’s reports asked where all the Latitude money went, showed that former Latitude employees’ unemployment benefits were being withheld, and detailed some of the allegations in Craig Phillips’s resignation letter. In January, she asked Brown about employees' paychecks bouncing. “He assured me, ‘These employees are getting paid, we switched our payroll system — they weren’t paid, now they’re going to be, and now everything’s going to be just fine,’” she said. “And it wasn’t.”

Bourne continued, “I did end up telling that story — I got some employees to send me the backs of their paychecks saying banks weren’t accepting them. And when I aired that story, even more tips started coming in. This time from investors, more employees, from contractors. It was like, where there’s smoke, there’s fire. But it was more than that: It was like, where there’s fire, there’s a supernova volcano blazing inferno.”

Employees were in a particularly tough spot. In March, I reported for Pittsburgh Business Times about a protest staged outside Latitude’s Pittsburgh location. Employees claimed they were owed $15,000 in back pay. “Because our employer has refused to pay us for the past month, I am now completely broke — I can’t afford the simplest of things like washing my own clothes,” said Laura Scimio, a former Latitude server. About 30 employees showed up that day, but the venue had already closed. Many of those workers have since stated that their paychecks remain unpaid.

Brown seemed unsympathetic when it came to concerns about bounced paychecks. “As far as the media, it’s like, ‘Brown owes the employees,’” Brown told me. “I don’t owe the employees shit. I don’t owe anybody shit. The company owes me money, and I’m an employee of the company, but I owe millions.”

After Bourne’s story about the bouncing employee paychecks aired in December, Brown refused to answer her calls, she said. Bourne would attempt to corner Brown while he ran errands or showed up for a deposition. “He has publicly called me a liar, yet he has been unable to disprove a single thing that I’ve reported,” she said. “I have offered repeatedly to do a formal sit-down interview with him, to give him the chance to tell his side of the story and be transparent, and he won’t do it.”

To be transparent, Brown would have to answer some basic questions: Why did he allow Latitude to write bad checks to its employees? Why hasn’t he paid back his debts to contractors? Why hasn’t he made a substantial effort to show courts and shareholders what exactly Latitude was spending its money on? And, beyond all of this: Why hasn’t Brown filed bankruptcy?

When I asked Brown those questions, his answers were audacious but unsurprising. He said he didn’t know the company was writing bad checks. (Such tasks are the chief financial officer’s job, he said, or that of Latitude's payroll company.) He hasn’t paid his debts because he and the company are flatly out of cash. He has made an effort, he insisted, to be transparent about his accounting — but his creditors simply don’t like what they’re being told (that he and the company are out of cash). And he hasn’t filed bankruptcy, he said, because he still thinks he can somehow revive Latitude.

“I’m fighting for the shareholders,” he said, “because I know if I file bankruptcy … everybody gets wiped out.”

Brown’s plan for reviving Latitude centered around a settlement agreement he negotiated with EPR, the landlord for Latitude’s Jacksonville and Indianapolis locations, to wipe away the millions that Latitude owed in back rent. Latitude would have to close the Jacksonville and Indianapolis locations in order to focus on perfecting the Pittsburgh location — and then expand, with more investment from shareholders, to all the other cities Latitude had previously intended to enter and more.

In Brown’s view, Aaron Riley, Jenna Bourne, and James Fonseca killed any possibility that Brown could carry out his revival plan. “It’s really a situation in which you have opportunistic reporters, right?” Brown said. "I think that some of the things that were said were baseless and unethical, and I can’t believe it can be done.”

In that pizza shop in June, Brown showed me a slideshow presentation he’d made that spelled out a web of conspiracy: Riley, Fonseca, and Aujla had enlisted Bourne to defile Brown’s reputation and that of Latitude itself. Bourne’s reporting is the most public layer of their scheme, Brown told me. He insisted that both Bourne and Riley were being paid by Fonseca. (They all denied that allegation.) To Brown, Bourne’s reporting is its own form of trolling that stems from Riley’s efforts. And it’s caused harm, Brown said, by hampering his ability to raise cash, to rebuild the company. He plans to file a lawsuit against Riley, Fonseca, Bourne, and others before the year’s out.

“When you hurt a brand, like [these] people have done, and then you expect that brand to go out and raise funding to pay the employees?” he said during a phone call, his voice rising in anger. “Now, you know, I’m sitting in front of people that were foaming at the mouth to get the brand Latitude 360. Now they’re like, ‘Eh, I don’t know.’ And all for what? Because we owed money to people? Well, it’s a startup that needs funding at a critical time. I mean, it needs money.”

From our very first conversations in April this year, Brown seemed to decide that he’d gotten nowhere trying to explain himself to Jenna Bourne, and that he’d instead have to make a case to me that he’d committed no crimes, and that his enemies — Riley, Fonseca, the Aujlas, Shear, Phillips, and anyone else who questioned where millions in Latitude funding had gone — were the real crooks. When the world heard his full story, he’d be vindicated and, in a business sense, reborn. There were times when I’d get flurries of text messages from him — sometimes 20 or 30 of them in a row — spelling out the ways that Riley and his crew had lied about him, or the new projects that would help him rebuild his reputation and his company.

One of Brown’s last potential deals involved franchising Latitude to a Qatar-based company, Al Sedriyah, which agreed to build a stand-alone Latitude 360 Grille. Brown was outwardly optimistic with me about the continuing relationship there; he was convinced that Latitude could grow in the Middle East, despite the pressure on him in the United States.

In June, I sent an email to a general account associated with Al Sedriyah asking about the state of Latitude 360 Grille and who was involved in the project. I also called a phone number listed on the company’s website. I never received a response to my email, and the number I called rang 30 times, without a voicemail picking up. But the next day, Brent called me frantic, angry: “Who are you calling at Al Sedriyah, man?! You’re fucking things up!”

It was difficult to get him to talk about anything not pertaining to Latitude during the three days in early June I spent with him in Jacksonville, tagging along to court hearings (which he did not object to my attending) and meetings with potential investors (which he did). At one point that week, we drove in his Range Rover to a court hearing in Craig Phillips's lawsuit against Brown. We waited in an empty hallway for a Duval County judge to call us into a small meeting room. There was an echo in the corridor, so we spoke softly, sitting across from each other on benches. I asked him about his hobbies. Someone had told me Brown liked to ride motorcycles.

“What do you ride?” I asked.

“I used to, man,” he said. “Harleys. But not anymore.”

“Why not?”

“Car accident,” he said, referencing a car crash in August that left him briefly hospitalized.

Silence followed.

In hours of in-person conversation over three days — and in hundreds of text messages and phone calls over months — any attempt to broach another topic was brushed aside. He would bring up his wife and kids on occasion, but only in the context of how they’d been affected by the company’s hardships.

Robert Shear, the early Latitude investor, told me that Brown has, from Latitude’s inception, been so focused on raising money “that he doesn’t care who it hurts — as long as he comes out clean and with plenty of money in his pocket.” That Brown continues to be accused of falsifying financial documents and failing to pay debts did not surprise Shear. What did surprise him, he said, was Brown’s unwillingness to show remorse.

Brown did not see it that way. Instead, Brown told me that he was always in a fight for survival with Latitude. When raising money, he told people what they needed to hear so he could keep the company going. If a lender asked him to sign a promissory note on a loan, he’d sign it, even if he knew that he had no possible way to pay it back on his own. When EPR Properties asked him to sign a forbearance agreement as part of its lease to Latitude on properties in Jacksonville and Indianapolis, for example, Brown signed it, putting himself at risk for the betterment of the company, he said. “I was forced to sign EPR forbearance agreement or they would not allow us to continue,” he wrote in an email to me. “Latitude then would lose 75% of revenue and over 300 employees out of job along with $24mm in paid in capital gone.”

And with enough cash, he told me, he would’ve eventually paid off or restructured all the company’s debt, restarted the business, and taken advantage of Latitude’s popularity. The Jacksonville location alone reeled in more than $12 million in 2015, despite the bad press; it was easily profitable, Brown said, and the venue’s best year to date. And while the Indianapolis location tended to lose money, Brown said, the Pittsburgh location had done well and was growing before EPR, the company’s landlord in Jacksonville and Indianapolis, sued, making long-standing debt issues public.

Those issues would have inevitably brought negative attention, whether or not EPR sued. In December 2015, a Duval County judge ruled that Craig Phillips should be compensated with 1.2 million Latitude shares, and $115,000 at an interest rate of 4.75%. Brown has not paid a dime of that amount and has filed court documents disputing Phillips’s claims. (In an email, Brown argued that Phillips’s claims are invalid, that Phillips was on Latitude bank accounts, and that he had the ability to audit and review Latitude expenditures: “[H]e was the CFO and needs to review fiduciary responsibilities of a CFO,” Brown wrote, adding that Phillips “is full of BS.”) In the meantime, the pressure on Brown has only intensified. Brown and Latitude were hit with another judgment in April — this one for $4.3 million in the case filed by Swiss investor Karl Wadsack, for an unpaid loan. Fifth Third Bank sued Brown and Latitude in May for failure to pay back a $3 million loan.

Then, in late June, when a 64-year-old process server attempted to serve Brown court papers related to Riley’s lawsuit, Brown allegedly attempted to run the woman over with his Range Rover. The woman spoke to Jenna Bourne, saying that Brown “should be ashamed of himself, as a man.” On a cell phone video taken on the scene, Brown aggressively denied that he’d done anything wrong: “You attacked me. You slammed my car, damaged my car,” he said. Then he filed a police report against the woman, writing that an “unidentified lady stepped in front of my vehicle” and then “slammed her arms on the hood.” Neither the incident nor Brown’s response did anything to lessen the attention on him or Latitude. Multiple news outlets in Jacksonville carried the story.

Latitude even lost a judgment to the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers for failing to pay royalties on popular songs it was playing in its venues. That judgment has not been paid, and Brown has declined to appear for post-judgment court proceedings in that case.

As the pressure grows, Brown continues to fight. Representing himself in court, Brown has denied the accusations from Tommy and Linda Tharp — the elderly couple who alleged that Brown convinced them to loan their 401(k) savings to Latitude, and then never received their money back — and that case is set for trial in April 2017. (In an email, Brown argued that the deal with the Tharps was invalid because he didn’t actually sign the promissory note that was issued to them.) Last month, he filed a motion to vacate the court’s $4.3 million judgment in the Wadsack case.

Brown has also seemed to contradict his own statements. He issued a press release in January saying that Latitude’s settlement agreement with EPR would help the company grow, allow it to minimize its overall debt, and help it focus on building more profitable venues. Then, in August, he filed a motion to vacate the settlement completely. He had "no financial means to justify signing forbearance or settlement agreements,” according to the filing: “As an individual, representing myself, I feel I was not in sound mind and body to execute the Settlement Agreement back in January,” he wrote. “The company had an independent board along with legal counsel to vote on signing the Settlement Agreement and represent the company. I only had myself and I was still suffering from the head injuries resulting from the automobile accident in August."

Brown deflected questions about financial wrongdoing by saying that Latitude is a public company, and that the financial documents it filed with the US Securities and Exchange Commission were audited by three separate accounting firms that “would go to jail if those documents weren’t right.” Latitude hasn’t filed a quarterly financial report since August 2015, however. And a month later, it filed a form stating that every report Latitude has ever filed except one “should no longer be relied upon.”

Bill Keep is dean of the business school at the College of New Jersey, and he has focused his academic work on business ethics and assessing whether companies have violated SEC rules in their operations. “This is not a Ponzi scheme in the technical sense, which relies on the perception of providing an unusually high return on investment in order to get more people to voluntarily invest,” Keep wrote in an email. “While there are lots of questions yet to be answered, this also does not appear to be simply poor money management or incompetence. It appears to be a situation where the owners extracted money at a rate not justified by the firm’s financials."

Latitude shareholders have been saying as much for months. Riley has alleged — on social media, on websites like Ripoff Report, and even on a billboard that Riley paid to have driven around Jacksonville — that Brown was plainly ripping the company off. "They raised $100 million to build a retail brick-and-mortar business and they don't own anything," Riley said. "Not even the silverware. Us investors didn't invest in Latitude, we invested in Brent Brown's lifestyle." ("I do want to improve optics," Brown said in an email regarding his perceived wealth in the face of financial crisis. "Should I die? Should I cut my arm off? Should I move my family into HUD housing?")

Assessing whether or not Brown has committed financial crimes might prove a longer wait than Riley would prefer. Florida State Attorney Angela Corey told Bourne on Aug. 12, “I’m just stunned that this can still happen in this day and age," and said that she was actively investigating the company. But Corey lost her Aug. 30 primary election, leaving the status of the investigation unclear. No other government entity has formally announced an investigation into Latitude or Brown.

Meanwhile, Brown has skipped depositions in at least two lawsuits against him. In June, I witnessed Brown showing up to a court appearance in the Craig Phillips lawsuit without financial records that would’ve helped to bring that case toward a conclusion. Three weeks later, Jenna Bourne arrived with a cameraperson at a deposition, and Brown walked out when he saw her there. Brown has faced possible contempt charges in at least one case, which could have sent him to lockup on technicalities. But so far, no court has taken such a step.

After we'd spent an hour and a half or so talking across a long table at V Pizza in June, the lunch crowd was getting loud, and whatever privacy we’d had was beginning to erode. He’d spoken loudly — robustly — but now that people were nearby, his voice was more like a whisper as he continued to insist he'd done no wrong. “Everything that I had is gone,” he said.

In the months that followed, Brown would tell me often that he felt he needed to leave Jacksonville. So it didn’t seem unreasonable that an ad appeared on Zillow on Sept. 3 offering his riverfront mansion for sale at a third of its estimated value. "This is a for sale by owner,” the ad read. “This is a fire sale. Cash buyers only. Needs to be able to close within 14 days. One of the premier homes on the river in Jacksonville. Fit for royalty. This deal will not last long."

It seemed like a last gasp for Brown — an indication that he might’ve finally given up, might’ve finally decided to cut his losses and run, just like Riley and others had suggested he might. But as quick as the ad went up, it was down again, the house unsold.

Riley would later admit to me that he’d heard rumors among real estate agents that CLS Asset Management — a holding company wholly owned by Brownstone Developers, whose owner and sole manager is Brent Brown — was quietly attempting to offload the house for $2.5 million. So Riley placed the ad himself to “list the house lower than the price [Brown] was requesting privately.” To Riley, it was part of a coordinated attack on Brown — just the latest attempt to make sure Brown paid for all the shareholder dollars he’d taken in and lost. To Brown it was harassment — yet another indication that there was a conspiracy against him. Despite his documented connections to CLS Asset Management, tax rolls listing the mansion as his home address, and the fact that he’d been served court papers there in a fiasco reported widely in Jacksonville media, he denied having any role in the house’s ownership or potential sale. Riley and his “goons,” as Brown called them, were merely making things up to ruin Brown’s life.

“Although I’m not a perfect person, I can promise, and swear to god, and swear to my children and my wife and everything else that I’m a good person, and I did nothing but put my heart and my blood, sweat, tears — everything into that company to build it into what it was,” Brown told me.

“And someday, the truth will come out,” he said. “It has to.” ●