Is JPMorgan too big? The question has been asked frequently by critics since the 2008 financial crisis lead to America's largest bank getting even bigger -- and paying out more than $20 billion in fines and penalties. And while being too big to fail attracts concern from one group of naysayers, doubts about its size have gained new credence after the bank announced today its profit fell by 6.6% in its most recent quarter compared to a year ago.

Earlier this month, a high-profile analyst report said the bank could be worth more broken up into pieces than it is today. That, plus worries about new regulatory requirements, has investors worried; JPMorgan stock fell 3.45% today to $56.81 today and is down 9.25% so far this year.

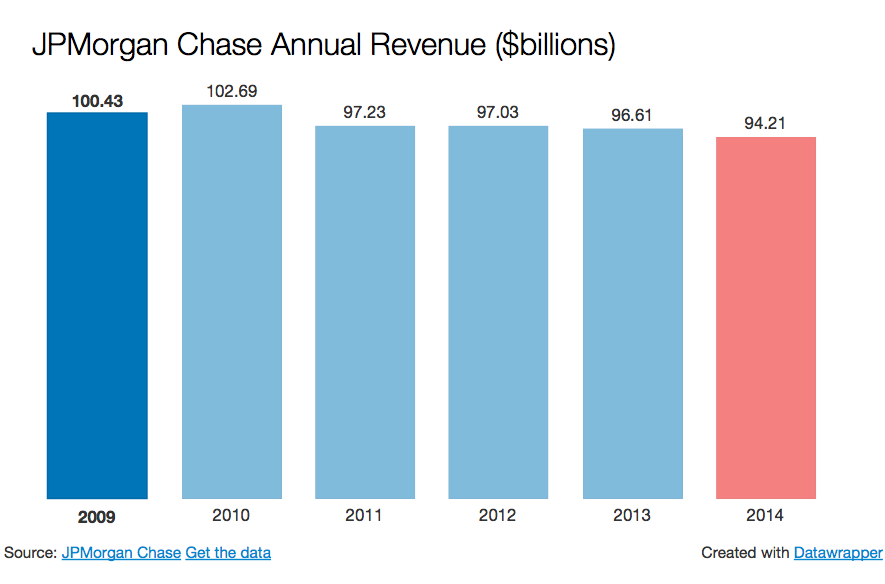

JPMorgan is unquestionably a behemoth: $2.6 trillion in assets, $757 billion worth of loans, $1.4 trillion in deposits, 241,000 employees all over the world, exposed to $65 trillion worth of derivatives trades. It has long argued that its size gives it unique advantages for its customers and shareholders, as well as healthily gushing revenue streams — $94.2 billion in 2014, $96.6 billion in 2013.

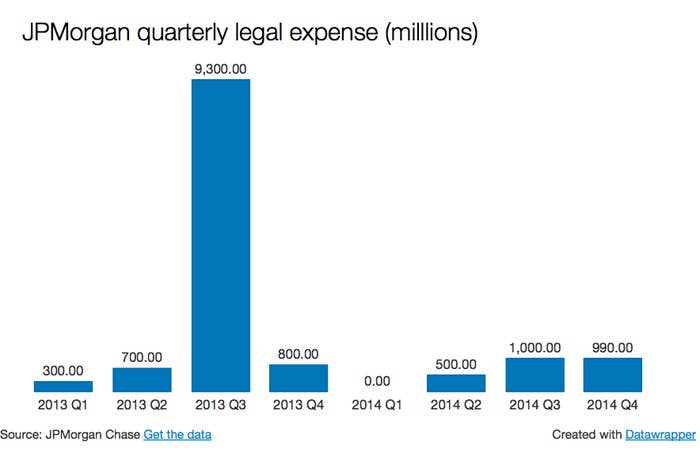

With that size comes vast exposure to the worst practices of the pre-crisis banking industry, and in 2013 alone the bank paid out more than $20 billion in fines and penalties, mostly related to the mortgage business of Washington Mutual and Bear Stearns, which JPMorgan acquired during the peak of the financial crisis in 2008. Large penalties also came for its dealings with Bernie Madoff, and the $6 billion derivatives loss attributed to a rogue trader known as the London Whale.

CLSA analyst Mike Mayo said in a December research report that the losses and fines show that JPMorgan "lost the peace" after years of successful empire building and expansion. The bleeding slowed in 2014, but there was still a more than $1 billion settlement with regulators over manipulation of the foreign exchange market and an ongoing Department of Justice investigation into its foreign exchange dealings.

"Banks are under assault," CEO Jamie Dimon said on a call with reporters on Wednesday. "We have five or six regulators coming at us on every issue" (on foreign exchange trading alone, there were penalties enacted by the Office of the Comtroller of the Currency, the Commodities Futures Trading Commission, and the U.K.'s Financial Conduct Authority).

The fourth's quarter disappoining profits didn't just come from sluggish revenue, but also from another quarter of high legal expense, this time $990 million, which finance chief Marianne Lake largely chalked up to the ongoing foreign exchange investigation. "I want to deal with this, acknowledge our mistakes, try to have a controlled balance sheet, try to stop stepping in dog shit which we do every now and then," Dimon said in reference to the bank's persistently high legal costs.

"When you have a market cap of $230 billion, I want to make it worth $500 billion ten years from now. You know, the several billion dollars that we're going to have to pay for legal stuff, we want to fix it. And it's unfortunate we do this to you all, but it's unavoidable."

While critics have longed pointed to JPMorgan as an example of why contemporary megabanks are too big to manage, a report in January by Goldman Sachs analyst Richard Ramdsen argued that JPMorgan might be also too big to generate the best possible profits.

Ramdsen wrote that in light of a Federal Reserve proposals to increase the minimum capital ratio of megabanks (basically restrictions on how much of JPMorgan's business can be funded through borrowing) to 11.5%, with only JPMorgan falling in the highest bracket, breaking up JPMorgan could create value. Four smaller businesses would have less punitive regulatory demands and thus higher returns for shareholders than one enormous one.

"All of its business lines are top quartile performers," Ramdsen wrote, "[which] implies enough strength to operate as standalone companies." Ramdsen estimated that JPMorgan trades at a 20% discount thanks to its size "and greater regulatory burden."

"There's a point at which the capital drag will be so high that you may want to

consider alternatives, but just remember they're not simple," Dimon said. "Every company has to have cash management, global trade ability, every company needs general ledgers and HR things and data centers and mirrored data centers and cyber security." Dimon also pointed to analyst research showing that JPMorgan's earnings were more consistent than its competitors, "The model works from the business standpoint, and yes, we'll have to carry more capital and we'll manage that over time."

But Mayo, the CLSA analyst who Dimon favorably cited on the call -- a change in tone from 2013, when Dimon answered one of Mayo's question's with "that's why I'm richer than you" -- asked about JPMorgan's apparent failure to push down costs, presumably one of the advantages scale should bring.

Lake noted that while the expense ratio, which JPMorgan calculates by dividing mostly non-legal expense by the bank's revenue, rose to 60% in 2014 from 59% in 2013, the increase was attributed to a slight decline in annual revenue. But she also noted that the total expenses are still falling. Going forward, she said, the bank was looking to cut costs in its branches and mortgage business. "Overall trending down, but, you know, revenues are part of the story."

But while running JPMorgan at its current size is clearly expensive, Dimon cautioned that the alternative could be more so.

"The unscrambling would be extraordnaily complex, and it would be

extraordinarily complex in debt, in systems, and technology and people," Dimon said on the call with analysts. He said that the bank could do other things to keep regulatory ratios and returns in a satisfactory range, including growing slower or limiting how many deposits it takes in. "We're not going to damage this franchise because of a current narrative," Dimon said, "That's not to say we're not going do the right thing for shareholders over time. We will."

He also argued that keeping JPMorgan at its current size and scale was a matter of public policy. "You're going to have some very large, very tough global competition over the next 20 years," Dimon said. "Do you want to see the next JPMorgan Chase be a Chinese company? Because someone is going to be serving the global multinationals around the world."

Dimon is adamant that the bank, on balance, benefits from its size more than it loses, but agrees about the scale of its regulatory burden. A major reason why JPMorgan could face a $22 billion capital shortfall under the Federal Reserve's new proposal is that it's deemed more complex that its peer banks.

Both Dimon and Lake had problems with the Fed's analysis. "It's not a measure of complexity, it's a measure of size," Dimon said. "The Fed proposal at year end is the biggest sign yet that JPMorgan is losing the argument," Mayo said.

Since the Fed released its proposal, JPMorgan's stock is down almost 10.5%, while the S&P 500 is down 2.7% and an index of financial stocks is down 5.82%.

"So if the regulators at the end of the day want JPMorgan to be split up, then that's what will have to happen," Dimon said. "We can't fight the federal government if that's their intent."